What we know already about the French political situation

France votes in the first round of the Presidential election on 10 April 2022, with the run off between the two best-placed candidates on the 24 April. A number of conclusions can already be drawn if the polls are generally correct:

- The first round votes will show the continued march of the French electorate into the arms of a racist, reactionary right which has a combined score of 31.5% in the polls.

- This shift to the right in politics and ideology has also been seen in the traditional right of centre party, LR (the Republicans) and in Macron’s LREM (Republic on the March) government.

- The left in all its variants will lose heavily. If you exclude the revolutionary left, the left are polling at about 20%. Hollande, the last president but one, was a PS (Socialist Party) leader; its current candidate, Hidalgo, is credited with 2.4% only – two points less than the Communist Party leader, Roussel.

- The revolutionary left could win between 2% to 3% – a far cry from the 10% they got in 2002, and the NPA (New Anti-Capitalist Party) candidate, Philippe Poutou, is fighting hard to get another 300 mayor/MP signatures that he needs in last few weeks in order to even stand.

- Despite the good scores for the Ecologists in the 2020 local elections, when it won a number of big towns, its presidential candidate is stuck at the moment on around 5%.

- Unless there is a total turnaround in the polls, the odds are on a run off between Macron, the incumbent, and either Marine Le Pen (it would be her 2nd time in a row in the second round) or Valérie Pécresse (for LR, mainstream right wing). However it cannot be excluded that Zemmour, the most reactionary of all the right wing could sneak through – the polls are very close between these three.

- Macron is well placed to beat any of the three right wing candidates although he may find it most difficult against the traditional right of centre Pécresse. In that eventuality, Macron would benefit less from the tactical voting of progressive and left voters to stop the far right

How do the French presidential elections work?

Political power in France, following De Gaulle’s establishment of the 5th Republic in 1958, lies in the hands of the president rather than parliament. After the presidential elections there are always parliamentary elections which tend to favour the winning candidate. Consequently the prime minister, who is appointed by the President, is always less powerful than them. You can have a parliament that is of a different political composition to the presidential majority and this has happened 3 times, most recently in 1997-2002. This was more common during the seven year presidential term which was shortened to five years in 2000.

The presidential election takes place over two rounds unless a candidate wins more than 50%. To be a candidate you have to get 500 signatures from mayors, other national or local elected officials. There has to be certain geographical spread to the signatories. This rule does open it up to left wing parties without current parliamentary representation. Nevertheless to get 500 signatures you need a national network of activists and is never easy.

The two main revolutionary left wing parties in France, the NPA and Lutte Ouvière (Workers Struggle) have managed it on most occasions over the last decades. The names of the signatories are published and the big parties order their representatives not to give support to other parties. Activists have to travel many miles searching for independent democratic-minded mayors and others willing to give their signatures. Militants emphasise that the signature is a democratic gesture not a sign of agreement with their policies. Even candidates and groups with more mainstream support have complained about the democratic limitations of such a system.

Once the official campaign begins the media have to follow rules about their coverage and equal time is given in the debates. It is more democratic than the British system in this respect. Even over the last few months before the official campaign, the revolutionary left candidates have been given some airtime. For revolutionary socialist candidates this gives you a national platform every 5 years to get your message across and build support. An additional bonus is the reimbursement of your elections expenses if you reach a certain threshold of votes.

Particularly for the mainstream parties, if you fail to stand in the presidential elections you lose crucial visibility for the subsequent parliamentary election. This explains part of the difficulty for the broader left or green currents like the Socialist party, the CP and Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s France Insoumise (France Unbowed) to agree on a united left candidate in the first round.

Meet the candidates

Emmanuel Macron (LREM – The Republic on the March)

Macron is the current president and although not officially declared as a candidate it is certain he will stand for another term. All presidents take advantage of their position to be above the fray and not be limited by any fair coverage rules before the official campaign starts. His signatures have to be in like everyone else’s by the 4th March. In the meantime he is able to present himself as a key player on the international level, now by putting himself forward as a mediator in the Ukrainian crisis.

His political rise came after a period as a non-SP minister in the Hollande government. He resigned and formed his new movement LREM as a vehicle to propel his presidential bid in 2017. Presenting himself as a modern liberal but pro-business he managed to split the Socialist Party since he looked very much like a right-wing social democrat. The mass media predictably knelt before the youthful, pro-capitalist ‘moderniser’. He got lucky too given the chaos created in the traditional right wing LR when their favoured candidate had to step down following an expenses scandal involving his wife. What was left of the PS was divided over who should be the candidate. There was a credible threat from his left in the shape of Mélenchon with his populist left wing policies but his support was not quite broad enough to either beat Macron (5% in front ) or Le Pen (only 1.5% ahead of him).

Macron’s government has not reformed in favour of working people but has attempted to restructure how the state works to favour business interests. He tried to change the pension system so people would have to work longer for less. It showed how he wanted to redistribute state resources towards capital and away from workers. Similar ‘reforms’ around fuel tax duty increases led to the mass gilet jaunes (yellow vests) movement. Macron’s paper thin liberalism has been shown in the iron fist he has used against any form of mass protest. He has joined in the ‘culture’ wars by his government’s ideological offensive against what is referred to as ‘islamo-leftism’.

Local election results revealed how his movement has failed to embed itself as a national party. However given the weakness and disunity of the left of centre parties as well as the perceived reactionary threat of Éric Zemmour and Le Pen, Macron is well placed to hold on to his 25% electoral base to get through to the second round. Despite a decline in his popularity from 2017, Macron still stands to profit from a tactical vote in both rounds. Many moderate Socialist party voters will stay with him – the very low polls for the Socialist Party candidate shows this. At the same time Macron plays a ‘centrist’ game adroitly by integrating supporters from the mainstream right wing party – his prime minister, Jean Castex, came from the LR in 2020. It suits him if the far right appears to be strengthening and if Pécresse rides that wave. He can present himself as rallying all the moderate anti-reactionary right wing voters.

Valérie Pécresse. LR (the Republicans)

President of the Paris Region, Pécresse confounded predictions by defeating the favoured male competitors like Barnier in the LR primary election. That election was symptomatic of the right wing lurch in French politics because in the first round the hard right Ciotti narrowly topped the poll with 25.6% and got 40% in the run off. Ciotti is an open admirer of Zemmour, who is to the right of Le Pen.

At her 7000 strong rally in Paris Pécresse reflected this tendency by referring for the first time to the ‘great replacement’ racist argument that the so-called native French will become a minority in their own country. She also extolled ‘français de coeur et pas de papier’ – ‘real’ French people as opposed to naturalised ones. Pécresse also name checked ultra nationalists and racists like Renaud Camus (theorist of the great replacement), Maurras and Charles Péguy. Apart from more draconian limits of on immigration, including a wall around the European community she is also for the sacking of hundreds of thousands of state administrators.

After peaking at more than 18% in the polls ahead of Le Pen she has since fallen back and has drawn criticism for her lack lustre campaigning and performance at the rally with her all too obvious pitch to the Zemmour/Le Pen base. She is slightly behind Zemmour and two points back from Le Pen in the polls on 14.7%. Sarkozy, the former president, who retains some support amongst conservatives has been slow in coming forward to support her despite her entreaties. Although not as bad as the crisis in the SP, the right of centre party has still not yet recovered its role as the favoured political representative of the ruling class.

Marine Le Pen (RN – National Rally, formerly the National Front)

In 2017 Le Pen made it to the run off and got 33.9% of the vote. Her strategy in order to go further than this is to continue to try and detoxify the image of her current. She broke with her more openly neo-fascist father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, who lost to Chirac in the second round in 2002. Zemmour’s rise on the far right has been partly based on his accusation that Le Pen has become too moderate – as bad as Macron. Key cadre and even elected representatives have deserted. The MEP Nicolas Bay was summarily expelled and accused of leaking documents and information to Zemmour.

Nevertheless, Le Pen is resilient and has a significant personal following amongst the far right electorate. Her strategic aim is to replace the LR as the leadership of the right wing opposition. Her experience in 2017 and the difficulty of increasing her party’s parliamentary representation means she wants to continue to broaden her party’s appeal by eating into the traditional right’s support.

Indeed although Zemmour’s rise is a threat to her party it also allows her to put herself forward as the more respectable face of the hard right. Her anti-migrant rhetoric is less anti-Islamic than Zemmour’s and she openly confronts his deep misogyny. Zemmour is more neo-liberal and in favour of low taxes. Le Pen is concerned to appeal to her more working class, popular base by supporting social policies to defend their standard of living. She is an MP for a working-class area and her party has an organised base among those layers. Zemmour, on the other hand, draws his support from more middle class, intellectual and even bourgeois groups. Le Pen defends the idea of the Republic whereas Zemmour even questions the 1789 revolution and emphasises France as a nation with a Christian identity.

Some analysts have suggested that Le Pen could even benefit from Zemmour’s intervention as long of course that she beats him and Pécresse in the first round. If she gets to the run off she could benefit from a transfer of votes from Zemmour’s base. Similar to how the UKIP vote ended up helping Johnson in Britain, Zemmour may well mobilise parts of the electorate Le Pen was not able to reach, including new voters. Faced with Macron they may well go with Le Pen particularly if they think she will have to take account of some of Zemmour’s policies. At the same time Pécresse’s voters may go with Le Pen if she has been seen to be less extreme and more moderate than Zemmour.

Anne Hidalgo (PS – Socialist Party)

Hidalgo is the mayor of Paris but her campaign has been pretty much a disaster as she is currently on 2.4% in the polls and was only briefly as high as 8%. She has been squeezed on her right by Macron and on the left by Mélenchon and Roussel as well as by Jadot, the ecologist. What the PS really fears is that this could have a negative knock-on effect on their performance in the parliamentary elections. Already the party has fragmented and its apparatus is reduced, a further loss of seats could take it to the point of no return.

Hidalgo has turned this way and that to try and kick start her campaign. For a while she talked a lot about the need for a united left/green candidate. One interesting phenomenon has been the movement on the left and progressive circles for a single united candidate. This reflects a frustration at the division on the left. Hidalgo showed interest in this for a while but then retreated. Over 400,000 people voted in an unofficial primary organised by this movement.

The winner was Christiane Taubira, a black former justice minister in the Hollande government, who also talked a lot of herself as a possible unity candidate. Her intervention has further weakened the Hidalgo campaign. Currently she is polling at 3.0% just ahead of Hidalgo but without a party she is struggling to get 500 signatures and may withdraw. The Left Radical Party which she had hoped would support her has now failed to do so.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon (France Insoumise, France Unbowed)

Hidalgo, as if she had not been humiliated enough, was particularly angry with a statement from Segolene-Royal, former PS presidential candidate which stated that a ‘useful’ vote on the left would be for Mélenchon. Certainly he has the biggest support, polling at 10.8% at the moment, but this is only half of his first round score in 2017.

Previously he had been supported by the Communist Party which still has a certain activist base as well as many councillors and as small parliamentary group. Fed up with Mélenchon’s style of leadership and his taking decisions without really consulting with them, the Communists decided for the sake of their visibility that they needed to stand this time.

There was a period at the beginning of Mélenchon’s political emergence as he broke with the PS that he was able to draw not just the PC but also the radical or revolutionary left around him. However as well as his rather autocratic style some of his left populist policies lost him support to his left. There were the ambiguities on migration, the support for the French nuclear deterrent and the enthusiastic adoption of the French flag and the singing of the national anthem at his rallies. Despite that his programme is progressive and compares well with the Corbyn policies. The problem is that if he cannot pull together a broad front by involving all the left forces it just means another worthy but failed effort in the first round.

Fabien Roussel (PC – Communist Party)

One of the reasons it is difficult for Mélenchon to repeat his 2017 performance if the presence of the PC candidate, Roussel. He has crept up to 4.4% in the polls and has had a certain media impact. This is partly because he is putting himself forward as thoroughbred French person who likes his steak and chips, red wine and cheese. He has consciously harked back to the golden age of the French CP of the post war boom, defending workers’ living standards and unencumbered with all this ecological or ‘woke’ ideology concerned with eating too much meat or opposing hunting.

Like the Blue Labour advocates in Britain he presents himself as listening to ‘working class’ concerns on security so he went along to support a reactionary demonstration in Paris by the police associations. In terms of policies his campaign is not so different from Mlenchon. One of his main concerns is to do well enough to maintain a strong negotiating position in the traditional deals with the PS in local or regional elections.

Yannik Jadot (EELV – ecologists)

Just ahead of Roussel on 5% is the green candidate. He defeated the more radical feminist eco candidate, Rousseau, in the primary but has since fallen back in the polls. The Greens in France have done best in local elections. Voters perhaps identify better with the actions of green politicians dealing with issues in their local environment where councils can make planning or development decisions which have a more immediate effect. It reflects the looser affiliation of voters to the mainstream parties. Maybe they consider splitting their votes between a national orientation and a local green posture is the most effective way of greening politics as a whole.

Some polls have suggested an alliance between the ecologists and the PS would have led to a bigger impact and certainly it is difficult for Jadot to take off as long as he is considered a non-contender for the second round. Mélenchon in any case has a strong ecological side to his programme.

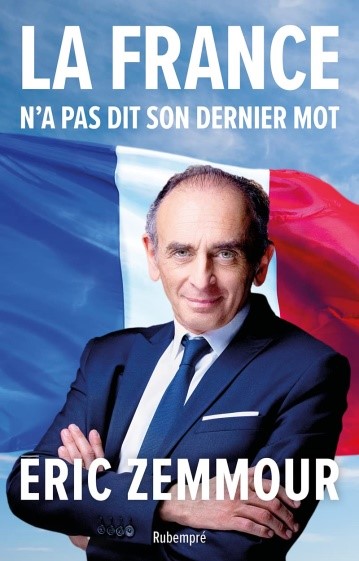

Éric Zemmour –Reconquete (Reconquest)

Zemmour’s entry onto the political scene is one of the factors in the droitisation (rightward shift) of French politics. Like Trump he was never a career politician but was a writer and columnist on right wing newspapers like Le Figaro. New right wing media outlets like the C News channel controlled by media tycoon Vincent Bollore has helped project him onto the national scene. Readers can consult a previous detailed article on Zemmour published on this website for detailed background and analysis on his impact.

Early on some polls even showed him beating Le Pen and getting into a run off with Macron. His ‘newness’ and lack of detailed exposure may explain that. He has consolidated for the moment within a few points of Le Pen and is it not impossible for him to come in second. Polls can sometimes underestimate the scores of extreme right candidates. Turnout could be another unknown factor distorting current projections. Turnout has been falling — as elsewhere in Europe – in recent elections. Once the official campaign starts detailed confrontation with other candidates and full exposure of his reactionary policies may lead to a decline in his popularity.

As we indicated above he draws to an extent on a different hard right and fascist heritage. Unlike Le Pen he whitewashes the role of Petain and his Vichy regime under German occupation in the Second World War. He claims falsely that he saved many Jewish people from the Holocaust. Traditionalist right wing Catholics who mobilised against gay rights form part of his activist base. Rather abstract ideas about French identity play a bigger role in his support than the social policies put forward by Le Pen. He has written books that are anti-feminist and misogynist. He has been convicted of racist offences several times. According to him non-French names like Mohammed would be forbidden. His constant theme is to whip up the false scare about white French people being submerged and replaced by non-white migrants. Like the RN he is in favour of repressive measures by the police and army to carry out his programme.

As our previous article on this site headlined, in one sense he has already won since he has to a degree set a new agenda. He is eroding support for both the RN and the LR. Win or lose he hopes he can play a role in reconstructing a more ideologically reactionary far right.

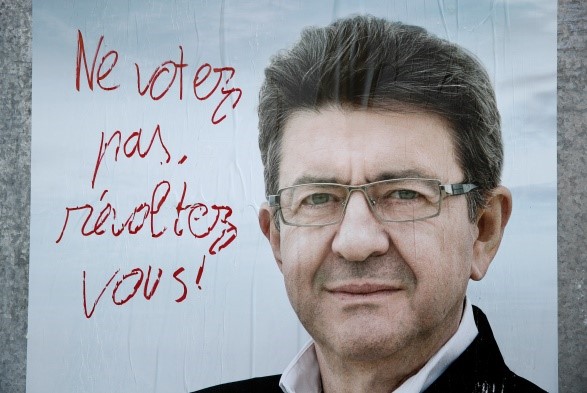

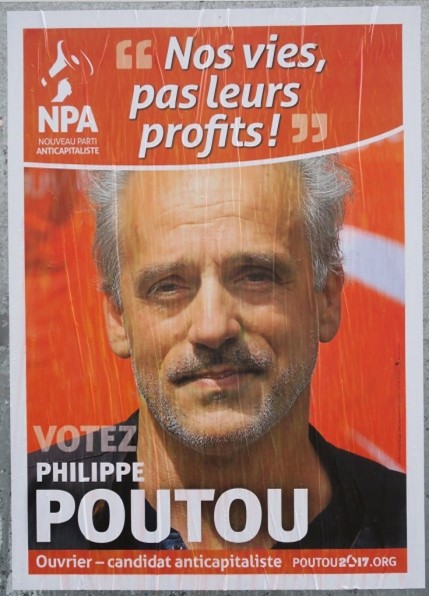

Philippe Poutou – New Anti-capitalist Party (NPA)

Former car worker, made redundant by Fords, and a local councillor in Bordeaux, Poutou is the third time candidate for this revolutionary party. He has scored just over 1% both times but made an impact with his intervention in several nationally televised debates. Currently he is drawing good numbers to his meetings but the scramble to get the 500 signatures will be very tight indeed.

The NPA is standing in the absence of any broader agreement within the radical or broad left for a united class struggle candidate. It recognises the difficult conditions for the left at this time but believes its intervention will raise the need for unity in action against the neo-liberal policies of the Macron government. Poutou presents a clearly anti-capitalist programme and propagandises about a completely different form of politics which does not rely on electoralism and merely occupying the current institutions. Whether the eventual victor is Macron or Pécresse or one of the hard right candidates the need to promote working class self-organisation remains a priority.

Nathalie Arthaud – Lutte Ouvrière (Workers Struggle) LO

She has also stood a number of times. LO has a long experience of continuously putting up presidential candidate and is almost certain to get the 500 signatures. This current has remained remarkably stable, neither growing particularly or declining drastically. It tends to plough its own furrow, not getting involved in developing united campaigns LO is rather workerist and prioritises intervention in factories and workplaces. Unlike the NPA is has never really got involved with Mélenchon or others in developing broad left mass currents. In recent elections it scores about the same as the NPA.

Anasse Kazib – Permanent Revolution

He is a child of immigrants and a railway worker whose current was up till last year a tendency inside the NPA. It considered the NPA majority as not ‘left’ enough; the majority considers it ultra-left and propagandistic in its approach. He has been a prominent activist in railway workers’ struggles. This tendency operated like an entrist group and is part of the international current dominated by the Argentine PST (Socialist Workers Party) which historically was connected to the Trotskyist leader, Moreno. A week ago he had even less signatures than Poutou so it is not at all certain that he will manage to be a candidate.

No gains likely for working people in this election

Given the polls today the result next April it is likely to be a defeat for working people. Total votes for the left on the first round will have some significance but it is likely to be absent from the run off. Working people will be faced with a Macron government mark 2 or a right wing one intent on aggressive reactionary policies.