Would you believe it? Just when these ‘creeping fascism’ people were expecting Donald Trump to unleash hordes of Brownshirts onto the streets of America, he goes and gets defeated in an election! Yes, the normal functioning of capitalist democracy! Which shows you just how far fetched the idea of creeping fascism was.

How do I know this is what some are saying? Because I read it on Facebook, obviously. Posted by John Rees. He says:

The passage of events is the harshest theoretical critic. The faults of the ‘creeping fascism’ ‘theory’ are now exposed by the ordinary workings of capitalist democracy. The disastrous weakness of this theory was not that it drew attention to Trump’s facilitation of the far right but that it so overestimated the threat that it disarmed resistance and disoriented activists.

The problems with Rees’s comments are threefold. First, he misunderstands what’s happening in the United States right now. Second, he’s evidently got a simplistic view of what the creeping fascism theory actually is. And third, it’s the complacency of people like him that disarms the movement in the face of the fascist threat.

As I argue below, the creeping fascism theory is about warning the Left and popular movements of the urgent need to combat directly the racist, xenophobic, and anti-immigrant wave that the far right are using to advance towards power – the mechanism used to elect Trump in America and secure Brexit in Britain. The real danger is that we sit back and adopt the Panglossian view that everything is back to ‘normal’.

Trump’s abortive coup

First on Trump. All perspectives are conditional, and Trump has not yet (mid-November) been prised out of the White House. Given the scale of his defeat, the clear blue water of six million more votes for Biden, it will be difficult to pull off an anti-democratic coup. If it had been as close as 2000, then you might have seen the Supreme Court find for Trump, or federal marshals being sent to seize ballot boxes. The fact that the ‘Million MAGA March’ on 14 November was a flop – only a few thousand hard-core Trumpists turned up – will have further discouraged support for this.

In the circumstances, any attempt by the Republican-packed Supreme Court to overturn the electoral verdict would probably cause a serious split in the state apparatus, and something like an uprising. Another route might be for state legislatures to overturn the result and nominate their own or extra delegates to the electoral college, but that would suffer from the same drawbacks. It is still not entirely excluded, but it does now look unlikely that Trump will pull off a coup.

If and when he is prised out of the While House, however, Trumpism and the American far right are far from defeated or banished from the political scene. Seventy million voters is an immense potential base for Trump. In the next few weeks and months, we may see Trump address mass rallies of his supporters to prepare them for further struggles. Trumpism, moreover, still has a firm grip on the Republican Party. Probably now there will be a combination tactic for the Trumpist right – inside and outside the Republican Party. Republican Congress people are unlikely to break with Trump, because his loyal mass base could finish them politically if they do.

After the Black Lives Matter protests, we saw something extraordinary – the mass mobilisation of armed militias on the streets. Politically these groups are fascist, even if they salute the Stars and Bars rather than the Swastika. In many places they have significant support inside local police forces. And there are tens of thousands of them. They are an important part of the Trump mass base.

Trump’s supporters are not a homogenous, finished fascist base. But many of them, millions of people, would clearly support the suppression of (bourgeois) democracy and its replacement with a dictatorial authoritarian regime.

It is not so clear that Trump will attempt to be the Republican candidate in 2024: a 78-year-old candidate may not seem viable. But as George Monbiot argues, the next Republican candidate could be a more competent authoritarian. He also points out that the new Biden government could be an interregnum before something much worse than the current Trump regime.

Assuming Biden takes over, what we are going to see now is a sustained campaign to besiege the new government. The hard right will use its control of the Supreme Court and its likely control of the Senate to obstruct Biden and back up states where abortion is banned, effectively ditching Roe vs Wade. Biden is a Catholic and it is far from clear that he will do much to oppose this. Obamacare (with all its limitations) is also likely to come under siege.

The Trumpist movement

Who are Trump’s 70 million supporters? Like many other far-right leaders, Trump’s most solid base is not in the working class, but among wealthier voters. One commentator puts it like this:

The Democrats’ electoral base is mostly in urban areas and includes lower-income, unionised, youth, precarious, Black, Latino, and LGBT sectors. The Republicans’ electoral base is concentrated in rural areas and includes voters that are male, white, middle-aged, and have incomes over $100,000 a year.

This is a very schematic thumbnail sketch; in any case, you don’t get 70 million votes without having a large swathe of working-class voters on your side. Like many fascist or far-right movements, Trumpism was successful in putting together a large section of the petty bourgeoisie and the rich with a significant chunk of the working class, including many white women.

The United States is deeply polarised, with all classes split on Trump and Trumpism. The coronavirus crisis and its economic impact, the depth of racism, the conquest of the Republicans by the hard right, and the likely stalemate between Biden and Congress – all of these things will deepen the polarisation and the political crisis.

Trump’s refusal to leave the White House is probably not at this stage an indicator that he is going to stage some last-minute attempted coup, but that he is building and consolidating the Trumpist mass base by stirring its sense that the election was ‘stolen’. There may be a partial parallel here with the Nazi myth that attributed Germany’s defeat in the First World War to a ‘stab in the back’ by socialist and liberal politicians.

In power, Trump and his supporters attempted to apply the tactic of gleichschaltung – using control over central levers of power to bring the whole state apparatus under control. The State Department has been purged, the Environmental Protection Agency has been purged, the security apparatus has been purged, and the Pentagon has been purged. Crucially, the Supreme Court has been stacked with far-right reactionaries.

The American Marxist John Bellamy Foster has from the beginning called Trump a ‘neo-fascist’. Nonetheless, soon after Trump’s 2016 election he was keen to point out crucial difference between Trumpism and 1930s fascism:

… key features distinguish neo-fascism in the contemporary United States from its precursors in early 20th century Europe. It is in many ways a unique form, sui generis. There is no paramilitary violence in the streets. There are no Blackshirts or Brownshirts, no Nazi Stormtroopers. There is, indeed, no separate fascist party.

An important part of this account can no longer be sustained. The modern analogues of fascist Blackshirts and Brownshirts have been on the streets and they have shot Black Lives Matter demonstrators. But in the march to Gilead they are likely to be an auxiliary force alongside the police, the border patrol, the army, and other armed bodies of the state – whose personnel are overwhelmingly right-wing and reactionary.

This aspect of authoritarian repression has been on display in attacks on the Black Lives Matter movement, where the Border Force was renamed ‘federal agents’ and sent to confront demonstrators in Portland and elsewhere. A modern authoritarian-fascist regime will not need to call on armed street-fighters as a central repressive force, because today’s repressive and ‘Panoptican’ surveillance state does not face an insurgent and possibly revolutionary working class, as the Nazis and Italian Fascists did in the 1920s and ‘30s. The police can be relied upon to do most of the work.

Biden’s victory has paused, but not ended, the fight for Gilead by American fascists and hard-right Republicans. The essence of what they want is the destruction of democracy – of effective voting rights, of radical media outlets, and of popular organisation in unions, campaigns, and movements of the oppressed. They want women, Black people, and LBGT+ communities put back in their place. They want to restore the apartheid system that ruled Black people’s lives until the 1960s. They want to send women back to the kitchen, and LBGT+ people back to the closet. This is the essence of the programme of modern fascism in America.

What do we mean by creeping fascism?

The creeping fascism theory more generally makes a series of analytical points about the rise of the reactionary right internationally. It is not an attempt to stick the label ‘fascist’ on every reactionary movement, but to understand the dynamics of the emergence and mobilisation of the modern analogues of classical fascism.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, fascists in France and elsewhere discussed the need to build broad nationalist parties which would have fascists at their core. That is what has been done successfully in France, Germany, and Austria, and, in a more complex and nuanced way, in Italy. The same process is now underway in Spain.

Most sectors of modern fascism have ditched the stiff-armed salutes and the jackboots. But they have not changed their programme. Enzo Traverso calls these parties, like the Front National in France and the AfD in Germany, ‘post-fascist’. The exact term doesn’t matter: understanding the process does. And modern fascist leaders have grasped an important historical lesson – fascists coming to power through a reactionary uprising is a rarity. They nearly always come to power through winning elections or being invited into government by existing reactionary regimes.

The disastrous economic crisis of 2008 produced a terrible response from the neoliberals in power, including the ‘extreme centre’ of the Blair/Obama type. Unable to chart an alternative to the catastrophic consequences of neoliberal financialisation – an alternative that might at least have included state regulation of investment and transactions – they turned instead to deficit financing (‘quantitative easing’), and sought to pay for it through savage austerity.

The endless economic and political crisis that ensued produced huge movements of protest and resistance, including Occupy!, the Indignados in Spain, repeated general strikes in Greece, the Gezi Park movement in Turkey, and, in a slightly different way, the Arab Spring.

As the ruling class faced the fury of sections of the popular masses, they turned to repression, with new laws against demonstrators and vicious police attacks on movements of resistance. But repression alone could not defeat these vast movements. The spaced was opened for disaffection to be channelled towards extreme-right, anti-immigrant, racist and fascist movements.

This culminated in the surge of the AfD in Germany, 30% for Marine Le Pen in the 2017 French presidential second round, the renovated Lega party joining with the Five Star Movement to form a government in Italy, the election of the Modi government in India, the consolidation of the dictatorial Viktor Orban government in Hungary, the authoritarian anti-abortion government in Poland, and of course the election of Donald Trump in the United States.

Creeping fascism: three theses

In talking about this process as ‘creeping fascism’, we kept in mind three things. First, the statement of Karl Polanyi in his famous book The Great Transformation: ‘The victory of fascism [in the 1930] was made virtually inevitable by the liberals’ obstruction of any reform involving planning, regulation, and control.’

We disagree with this statement, because Polanyi discounts the possibility of a socialist-revolutionary outcome to the crisis. But he is right to imply that the failure of mainstream, centrist, liberal politics to address the economic crisis and its social consequences creates the conditions for fascism.

The stability of bourgeois democracy since World War II has been built on relative economic prosperity and the historic growth in working-class living standards during the post-war boom. Destroy prosperity and welfare systems, and capitalist democracy, one way or another, is liable to collapse.

Second, we also took into account the thinking of Robert Kutzer in his book Can Democracy Survive Global Capitalism? His basic answer to his own question is ‘no’. More precisely, he argues:

Democratic capitalism today is a contradiction in terms. Globalisation under the auspice of finance-capital has steadily undermined the democratic constraints on capitalism. In a downward spiral, popular revulsion against predatory capitalism has strengthened populist ultra-nationalism and weakened democracy.

Because Kuttner is a social-democrat, he poses the issue as controlled capitalism versus authoritarian dictatorship. We pose the choices differently. But like Polanyi, Kuttner sees the far right as much more able to benefit from economic crisis and social collapse than the Left. The far right defends the power and prerogatives of capital, while the Left will face endless hostility from the right, capital, and their media.

Kuttner is surely right about neoliberal capitalism and democracy. It is not just a matter of closing down democratic rights of demonstration and assembly. It is also about crushing every space of resistance, inside and outside the national and local state. This involves ending public ownership and control, manipulating and rigging elections, attacking public-service broadcasting and critical media, purging the universities of critical teachers and content, and privatising national and local government functions so they escape popular oversight. This process inevitably leads to widespread corruption, and the dictators are often themselves immensely rich and corrupt (Erdoğan, Putin, and Xi Jinping are all billionaires).

Modern fascism

So the first part of our argument is that the giant crises which are upon us are incompatible with capitalist democracy. This should not surprise us. Bourgeois democracy has existed for a much shorter time than capitalism itself. Francis Fukuyama’s prediction that capitalist globalisation would lead to the victory of democracy everywhere has proved wrong on all counts.

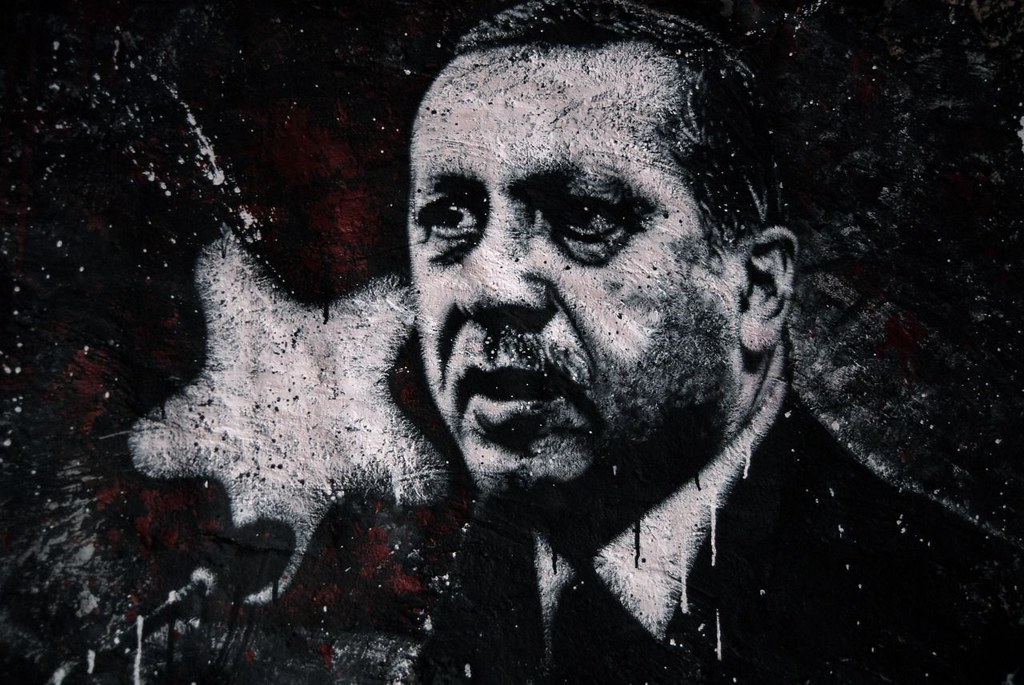

Our second part is that simple repression is rarely sufficient to defeat the popular masses, democracy, and the left. It generally involves also building a mass reactionary base. This is the genius of the project of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey. He has used the mass electoral base of the Islamist AKP party as his route to power, and then used his presidential position and parliamentary majority to successively purge the police, the army, the judiciary, the civil service, and the universities of all opponents and possible opponents, in a classic process of gleichschaltung. Combined with this, he has engineered the most brutal repression of all popular movements, especially the Kurdish-led HDP. Hundreds of thousands have been jailed, many thousands tortured, and tens of thousands of mainly Kurdish political militants killed.

Robert Kuttner brands both Erdoğan’s Turkey and Putin’s Russia as ‘soft fascism’, because although some of the forms of democracy, like managed elections, continue, they are rendered largely meaningless in practice. There are differences: Erdoğan has a mass party of immense power behind him (the AKP has 11 million members), whereas Putin’s United Russia (two million members) pivots much more on the state apparatus itself. But these are differences of degree, not type.

There are obvious differences, too, with interwar fascism. In the 1930s, a mass reactionary electoral base backed up armies of street-fighters needed to physically defeat the left and the workers’ movement on the streets. Nowadays, the surveillance state and militarised police forces render armed fascist militias – in most cases – redundant. However, the case of the United States shows that interaction between armed fascists and the repressive apparatuses of the state is ongoing and symbiotic. In major conflicts, the armed fascists, said to number tens of thousands, can be mobilised. Even in England and Scotland, we should not forget, extreme right-wing thugs have been on the streets – from the Tommy Robinson demonstrations, through the pro-Brexit protests, to the anti-lockdown movement – and they have not gone away.

Creeping fascism defeated?

If it is economic and social crisis that creates the opportunity for the far right and the slide towards fascism, these crises generate a polarisation – which Polanyi misses. Everywhere, there is mass resistance to the far right.

The most dramatic example in the last year, in the United States and internationally, was the Black Lives Matter movement, which had the active support of millions – workers, oppressed people, young people – and of course was met with vicious state repression and involved head-to-head confrontations with armed fascist militias.

In the last part of the year, we have seen: an upsurge of rebellion against the far-right regime in Poland, led by young women and focused especially on resisting new anti-abortion attacks; the sweeping left victory in the referendum in Chile, aimed at ditching a constitution that enshrines privatisation and neoliberalism; the return to power of the Movement Towards Socialism in Bolivia; and an exceptionally militant uprising against corruption and repression in Peru. The fall of Trump will demoralise the far right and embolden the resistance.

Karl Polanyi tends to pose the alternatives as liberalism or fascism. ‘If the liberals [and, I might add, the social-democrats] don’t introduce regulated capitalism, then the fascists can come to power.’

If that’s the real choice, we’re in trouble, because the aftermath of the 2008 crash showed clearly that liberals and social-democrats are not prepared to challenge the prerogatives of capital; in power or out, they stick with neoliberal austerity. The main exception, of course, was the Jeremy Corbyn movement in the Labour Party, and the war against him by the capitalist class and the right-wing of the Labour Party was really about his radical programme. Bernie Sanders in the United States was also a partial exception, and he too was the recipient of fierce hostility from the capitalist class and the right-wing of the Democrats.

The emerging forces of rebellion – workers, the youth, women, Black people (not, of course, exclusive categories) – are the real basis of the potential alternative, that of anti-capitalist transition (aka revolution). Yes, the stakes really are that high. We are not going back to the 1970s or the 1950s: either we make revolution or we risk fascism, militarisation, and ecological and social collapse.

A vivid example of the sustained danger of creeping fascism is the growth of Vox in the Spanish state. Vox raps itself in the colours of Castilian nationalism and resists federalism and the right of the different nations and regions to autonomy. It has highly reactionary positions on women and promotes dog-whistle homophobia. It self-consciously paints itself in Francoist garb in its reactionary Catholicism and xenophobic nationalism. And it has stolen most of the base of the allegedly middle-of-the-road new Ciudadanos (Citizens) party. Now it is cleverly putting itself at the head of anti-lockdown demonstrations in Madrid and elsewhere.

You cannot analyse parties like Vox with a template derived from the 1930s, checking for similarities to and differences from Nazism to decide whether they are ‘fascist’ or not. Vox is a modern analogue of 1930s fascism. It is a movement in process, and its dynamic and programme is towards fascism.

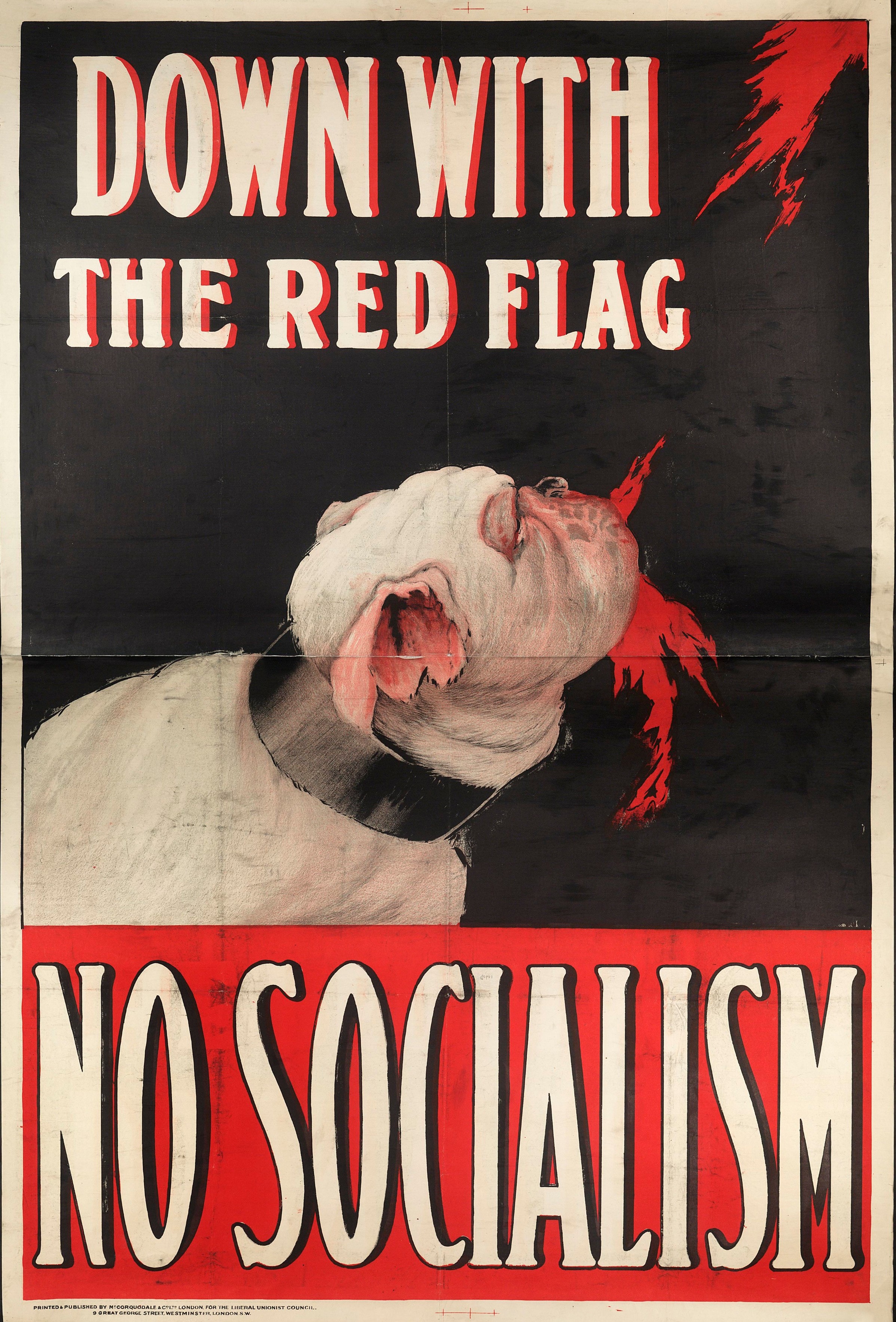

War on socialism

It was no surprise that the Cuban-American population of Florida was showered with anti-socialist messages by the Trump campaign. Mostly this is a reactionary community, gripped with hatred of the Communist government on Cuba, but also of the Chavist regime in Venezuela, from where comes an increasingly large exile population in the US.

But the Republicans onslaught against ‘socialism’ went much further. In his acceptance speech at the Republican convention, Donald Trump said: ‘This election will decide whether we save the American dream or whether we allow a socialist agenda to demolish our cherished destiny.’

Throughout the campaign, attacks on socialism were constant, as were attempts to paint Biden and Obama as socialists in league with Cuba and Venezuela. The content of these attacks was absurd, but the very fact of this discourse is significant. What is elided in the discussion is socialism and social-democracy – revolutionary transformation as opposed to wanting a decent health and welfare system.

But in the United States, recent polls show big majorities, especially in the 18-34 and over 55 age groups, with a positive image of socialism – as opposed to capitalism. Probably many of those with a positive view have in mind state-regulated welfare capitalism. But the hostility to capitalism is significant – and dangerous for the ruling class.

The attack on socialism in the US is a pre-emptive campaign against the emergence of a hardened socialist and class-struggle opposition to neoliberalism and the far right – as we see today represented by the Democratic Socialists of America. It is a pre-emptive strike against growing union opposition and militancy. It correctly identifies the real opposition to far-right America.

I finish by returning to Robert Kuttner’s question: can democracy survive global capitalism? Our answer is no. In the long term, the road to Gilead is open, as long as an anti-capitalist alternative is not built. And that alternative can only be built by direct confrontation with the major weapons of division used by the fascists and the far right – racism, homophobia, misogyny, xenophobia. In that fight we can shut the door on Gilead.

Phil Hearse is the joint author, with Sami Dathi, Neil Faulkner, and Seema Syeda, of Creeping Fascism: what it is and how to fight it.