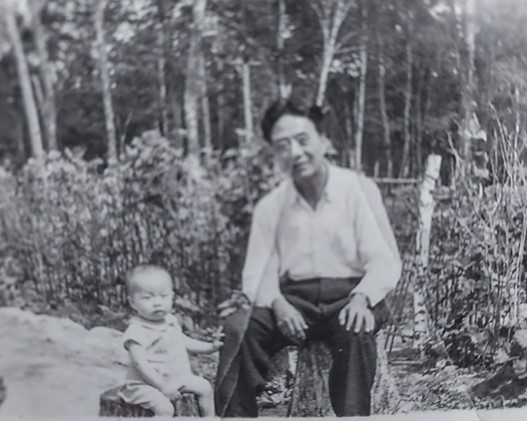

Wei Wei’s father, Ai Qing, was a poet with national acclaim. He was imprisoned by the reactionary regime in the 1930s, and he committed himself to the struggle to free China from Japanese colonialism and create a socialist future. He knew Mao and discussed literature with him in the liberated Ya’nan territory during the revolutionary war. However, he was denounced as a ‘rightist’ for defending artistic freedom in the 1950s and was exiled to a remote area and condemned to menial labour. He was later released, only to fall foul of the frenzied onslaught of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s. His son, Wei Wei, accompanied him into internal exile on both occasions. In 1980, after the death of Mao and the new turn of Deng’s reforms, he was released.

Ai Wei Wei became nationally and internationally known for his art and collaborated in the design of the beautiful ‘birds nest’ stadium for the 2008 Olympic Games. Like father, like son, Wei Wei refused to accept a comfortable life, keeping silent about the repression and abuses of the Chinese regime. So he was also detained for 80 days and was constantly monitored by the secret police. For a period, his interventions on the Internet drew millions of supporters. His sites, Twitter postings, and blogs were then taken down by the regime’s immense apparatus of social media monitors and controllers.

Ai Wei Wei paints us a fascinating portrait of Ai Qing, his father. Here is the poem that provides the title of the book: Even in translation, when we lose the musicality of the text, the words express sadness and anger about how tyrannical regimes try to control a people’s memory. Yet there is always an optimism, a counterforce, about living the best life you can despite all the difficulties.

The markets bustling as before An incessant flow of carts and horses But no –the splendid palace Has lapsed into ruin Of a thousand years of joys and sorrows Not a trace can be found You who are living, live the best life you can Don’t count on the earth to preserve memory (From Yarkhoto, 1980 Ai Qing)

During the various exiles, Ai Qing, denounced as an intellectual rightist, was obliged to do the most menial jobs like cleaning the toilets as well as being ridiculed in the compulsory camp education meetings. He would have to don a dunce hat during the Cultural Revolution (1966) so he could be laughed at and sneered at. However, he communicated an incredible dignity to his son, who remembers him not complaining about the labour he had to do and recalls his capacity to retain his fighting spirit and resistance. While having leadership responsibilities for artistic questions during his time in the liberated zone of Yan’an after 1940, he was already disagreeing with Mao about the rigid control the party wanted over artistic work. Nevertheless, Zhou Enlai and Mao both respected his work, and he was even invited to be involved in the selection of the new national flag.

Clearly, it would have been easy for Qing to choose an easy life, escape into his poetry, and compromise with the new regime. He actually believed that Mao was being sincere when he decreed, ‘let a hundred flowers bloom’. But as he caustically comments, the whole thing was a way to ‘tempt the snake out of its den’ so as to identify people not loyal to the party line.

Qing was internationally celebrated for his poetry and was friends with the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. They exchanged gifts, which both men treasured all their lives. After the thaw following the death of Mao and up to 1982, he published more than a hundred poems and travelled extensively in China and internationally, including to West Germany, Austria, and Italy. He read a poem about the Berlin Wall in Munich.

And how could it block Birds’ wings and the nightingale’s song And how could it block Water’s flow and currents of air? And how could it block the ideas Freer than the win Of thousands and millions of people? Or a resolve even firmer than the earth? Or a desire even longer than time? (Wall, 1979)

Ten years later, a young man would read this poem aloud at the foot of the Berlin Wall on the day it fell (p. 155).

On another level, this book is about the father-son relationship. The rigours and difficulties of exile meant they were close, sharing tiny living quarters, but there were also limits. Like many of us Ai Wei Wei regrets not being emotionally closer to his father and talking more. At one stage, the son almost drops out while staying in New York in the 1980s and does not seem particularly concerned about being a long way from his father.

On the face of it, Father’s impact on me was limited, for during his lifetime he had given me very little direct guidance. But to a large extent, that simply reflected my unwillingness to seek his advice. Had I sought his counsel, I don’t doubt that he would have responded. (…) like a star in the sky or a tree in a field he was always there as a compass point, and in a quiet and mysterious way he helped me navigate in a direction all my own. (p 209)

The research that has gone into the book to put together his father’s life and achievements is the best homage he could have made.

The rest of the book deals with Ai Wei Wei’s artistic and political development. He gives us a blow-by-blow account of his cat-and-mouse tussles with the Chinese regime and his rejection of autocracy and the pursuit of profit at all costs in the West. His championing of the cause of migrants and refugees is the clearest example of his refusal to take the side of the other ‘camp’.

He explains how his art cannot be anything else but political, given that his work is all about how truth and beauty are constrained by political forces.

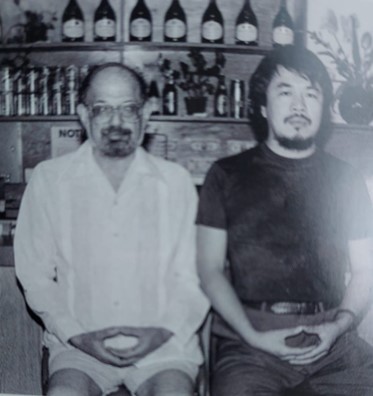

One lesser-known and rather surprising element in his artistic formation was the twelve years he spent based in New York between 1981 and 1993. He worked various low-paying jobs, dropped out of art school, sketched tourists to pay the rent, and exhibited some work in minor galleries. Ai Wei Wei did not set the world on fire at this time, but he did meet up with Allen Ginsberg, the poet, and Keith Haring, the graffiti artist. He spent a lot of time walking and thinking. He directly observed the New York finest cracking down on East Village protests against gentrification:

This experience served as a crash course in social activism, helping me understand the power of capital, the conflicts of interest between institutionalised power and the individual, and the necessity of upholding rights and freedoms in the face of threats and violence. (p 190)

Returning to China, he became much better known, particularly as a result of his collaboration on the design of the Olympic stadium in 2007. At that time of grandiose national promotion, he put his finger on the way the Cold War had changed into something different.

Belief and ideology were no longer the real battlefield. The real battlefield was profit—naked profit—spanning across regions, conglomerates and nations, inspired by the globalising dream of the capitalist powers. (p 251)

In the same year as the games, there had been a big earthquake in the Sichuan region. The regime controlled all the information about the extent of deaths and casualties and, above all, why the school buildings had been so flimsily constructed. So Wei Wei set up his art and political project. He visited the area, then recruited over a hundred volunteers just to find out some simple facts, such as the names of all the children who died. The authorities did not provide a list. Gradually, over a number of months, the artist was able to deliver a list. The list became a piece of art that he displayed.

This process showed some of the key features of his work. First, art is not seen just as some individual genius working in their studio but can be a social, cooperative process. Second, it addresses a burning issue of the day. Third, it is basically very simple and straightforward—how complicated is it to compile a list of dead children? The simplicity, of course, makes the work very accessible to the public. Later, he made another artwork using the broken and twisted steel from the ruins of the schools; this work was shown in an exhibition at the Royal Academy in London a few years ago.

Another striking feature of his work is a certain playfulness that he uses effectively against the authorities. When the regime decides to demolish his brand new studio that the local officials had signed off on, he organises a river crab feast for his supporters to ‘give the studio a proper send-off’ (p. 288). In Chinese, the two characters for river crab sound just the same as the characters that mean ‘harmony’. Harmony was an overriding political objective of the government. So the event was an ironic comment on the government’s propaganda and an implicit protest against the demolition. Despite harassment of people online who had responded positively to the invitation, over 800 people came, even when police detained Ai Wei Wei in his own home!

You can find other fascinating background information on how he put together some of his best-known works, like the sunflower seeds. But for me, the most moving and fascinating section of his book is the detailed account of his 81-day detention in 2011 by the authorities. There is a particular law in China that allows them to hold someone for up to 6 months in a facility outside the regular prison system without any formal constraints; you are denied legal representation and visitation rights. It is a bit like state kidnapping.

In this situation, you are under 24-hour surveillance with two guards that are constantly with you, even in the bathroom and while you sleep at night. Many hours are spent in interrogation each day, too. The objective for the state, as it was in the Stalinist system of the old USSR, was to extract a signed confession. You are allowed minimal exercise inside the prison, having to march up and down the room alongside the guards. True, one is not beaten or physically tortured with electric shocks or worse, but it does take a physical and psychological toll.

The empathy and political maturity of Wei Wei are exemplified by his efforts to understand and eventually communicate with the guards. As you might expect, they are not informed much about what they are doing and are recruited from the poorest areas of China. He also manages to reach a level of understanding with the interrogator. Wei Wei knows that a lot of the people administering the system are doing it because they need a job or do not wish to rock the boat; they are not all convinced ideologues or assassins.

Following his release, once again Wei Wei creates art out of his struggles. I remember seeing the mini-reconstruction of his prison in the Royal Academy exhibition. In his Brooklyn Museum exhibition, he did not just dwell on his spell as a political prisoner; he also made mosaic pictures out of Lego of 176 political prisoners from around the world. At one stage, Lego, under pressure from the Chinese government, stopped supplying him. The response was that people from all over China sent him Lego so he could continue his work. His art is really part of a sociological or political process.

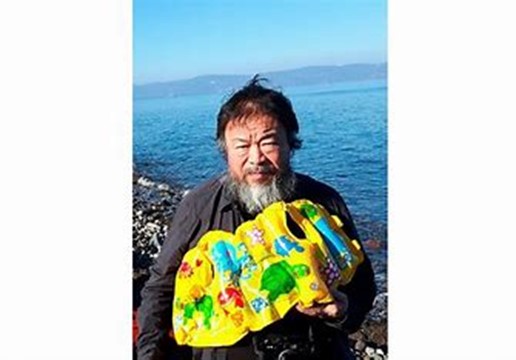

In a campaign to get his passport back, he put a bicycle outside his studio and put flowers in the front basket. These were renewed regularly and posted on Instagram; thousands followed. However, it became impossible for him to work anymore in China. He finally got his passport back, and since 2015 he has been living in Berlin, Cambridge, and Portugal. One of the recent themes in his work has been the plight of refugees and migrants. He has made installations of lifejackets and a successful film. In the final pages of the book, Wei Wei is very concerned about being a good father to his son.

The fates of our three generations—my father’s, my son’s and my own—are tightly linked to the fates of countless people we have never met and will never know. This gives me all the more reason to say what’s in my heart, to share it with others, and to make myself heard. Self expression is central to human existence. Without the sound of human voices, without warmth and colour in our lives, without attentive glances, Earth is just an insensate rock suspended in space.

These are the words that ring in my mind when I read or hear someone on the left going on about how China is standing up to imperialism or is some sort of ersatz socialist state because poverty has been significantly reduced there.

l000 Years of Joys and Sorrows (Vintage 2021)

Latest Articles

- Capitalism kills womenThe violence of patriarchal capitalism does not discriminate based on race, class, nationality or gender identity. We need to work together across oppressions if we are to stand any chance of reversing the damage already done argues Sandra Wyman.

- Defending women’s rights against the far‑rightWith the far right on the rise, it is vital to defend and extend women’s rights. Liz Lawrence writes about what the spread of nostalgia politics means for women.

- 8 March: Long Live Women in Struggle Against the Far RightAll over the world, women are promoting networks of solidarity, forms of protection and denunciation against all violence, whether domestic, imperialist military or fascist. Women are building forms of resistance in their territories against hunger, poverty, wars, extractivism, climate collapse and deprivation of rights. Motion adopted by the International Committee of the Fourth International.

- Ukraine UnbrokenDave Kellaway reviews Ukraine Unbroken, five plays about the history of the Ukrainian conflcit

- Solidarity with the Ukrainian peopleStatement approved by the International Committee (IC) of the Fourth International on 25 February 2026.