Undoubtedly, Debord’s greatest achievement was his theory of ‘the Spectacle’ first aired in his 1967 book The Society of the Spectacle. We are all slaves to the Spectacle. A society whose desires are neutered and put to sleep by the Spectacle. The Spectacle of consumerism, entertainment, escapism, work, politics. In 2001 the Spectacle became terrorism, as in a terrorist ‘Spectacular’. Now the Spectacle has turned in on itself. We live in a world of virtual reality and social media, a rabbit hole of somebody else’s design, unable to see the virtual wood for the virtual trees.

Luke Haines[1]

Guy Debord is a time bomb, and a difficult one to defuse. And yet people have tried. And they are still trying. They try to neutralise him, to water him down, to aestheticise him or to deny his originality. It never works. The dynamite is still there, and it might explode in the hands of anyone who picks it up and tries to render it inoffensive.

Michael Löwy[2]

Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle[3](1967) represents the culmination of efforts by 20th century Marxists to theorise the ideological means by which the capitalist class dominates, or attempts to dominate, the consciousness of significant sections of the masses – in advanced capitalist countries to start with, and now worldwide.

These efforts effectively began with Antonio Gramsci and his concept of hegemony (more or less, domination). Bourgeois hegemony is exercised both by force and by gaining the consent (grudging or otherwise) of the masses, who are made to see capitalist society as being either just or inevitable. For Gramsci, this consent is gained by capitalist domination of ‘civil society’, which includes the mechanisms of ideological domination, e.g. the Church, the education system, the popular press and other media, the legal system, and the mass political parties. This is in addition to direct bourgeois control of the state apparatus, which, together with the family, also relays bourgeois ideology. Together these things generated a pro-capitalist ‘common sense’.

Gramsci wrote in the 1920s and 30s, however, at a time when consumer capitalism and the broadcast media were in their infancy: he was never really in the right place nor had the time to think through how the different forms of mass consumption and communication were changing the processes of ideological domination, and the ways in which the working class and other popular social layers ‘saw’ the world – literally and metaphorically.

But in the early 1930s, major changes were being made in the mass media and in political display, changes that generated a new, more dramatic and all-embracing image of the world. These included changes in political mobilisation, and the extraordinary breakthrough made by the mass movie market when the ‘talkies’ arrived.

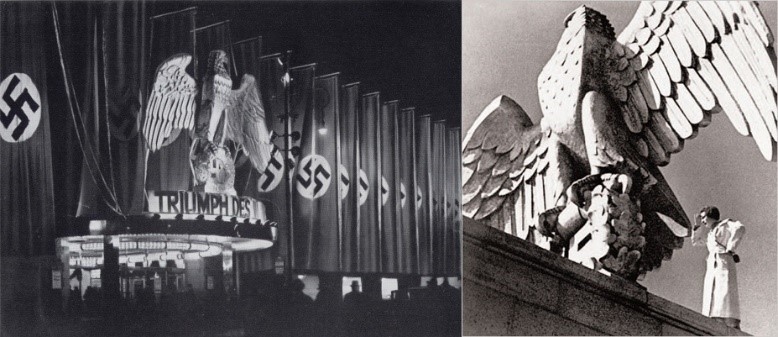

The Nazis utilised and developed the iconography of the workers movement (red flags, mass demonstrations) and took it to a whole new level. This intersected with the movies in Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 documentary Triumph of the Will, which documented the 1935 Nuremburg rally.

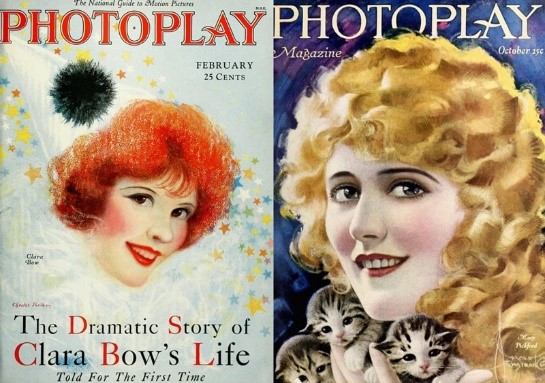

At the same time, the big film studios deliberately launched a new form of celebrity culture, by setting up film magazines that specialised in personal gossip. In the era of the Great Depression and mass poverty, a compensatory dream-world about the rich and famous was enabled by movie stars and their interaction with wealthy figures like business people and sports personalities (who were among the first modern celebrities).

Debord’s spectacles

The Society of the Spectacle was published after the post-war boom had generated a vast new range of consumer goods and a whole world of TV, movies, pop music, advertising, and fashion. The ‘life-world’[4] of the masses was increasingly shaped by the huge avalanche of commodities and images. This was spurred by celebrity culture and its essential medium – photography. By the end of the 1960s, hundreds of millions of people could identify from photos or news clips people like Elvis Presley, Muhammed Ali, Marilyn Monroe, The Beatles, Jackie Kennedy – and dozens of others.

Debord theorised that this had created a new stage of capitalism where the vast array of consumer goods and images had fused to create a series of ‘spectacles’, which in turn had fused to create one giant Spectacle.

In the 1960s student movement, the notion of the commodity spectacle of late capitalism was commonplace. But some formulations in Debord’s theorisation in his 1967 text were arguably exaggerated. The very first Thesis in his Society of the Spectacle claims: ‘In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.’ (My emphases.)

Clearly everything that was once lived has not moved away into a representation. There are images of war, but there are also real wars. There are images of car crashes, but there are also real ones. There are images of factories, but also real factories. It would be much more accurate to say that our participation in social reality, and out understanding of it, is modified and even dominated by its spectacular presentation.

The French postmodernist philosopher Jean Baudrillard took Debord’s ideas one step further and claimed that everything was now an image, that the image preceded reality, and notoriously that ‘he Gulf War never happened’. Insofar as Debord tended in the direction of saying the image was more important than the reality, then he made a mistake, or rather an exaggeration. But an exaggeration with a purpose.

Debord is much more precise when a couple of paragraphs later he claims: ‘As a part of society it (the Spectacle) is specifically the sector which concentrates all gazing and all consciousness. Due to the very fact that this sector is separate, it is the common ground of the deceived gaze and of false consciousness, and the unification it achieves is nothing but an official language of generalised separation… The Spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.’ (My emphases.)

Debord’s materialism

Even more precise and telling is the following passage, which I take to be the core of Debord’s theory:

The Spectacle grasped in its totality is both the result and the project of the existing mode of production. It is not a supplement to the real world, an additional decoration. It is the heart of the unrealism of the real society. In all its specific forms, as information or propaganda, as advertisement or direct entertainment consumption, the Spectacle is the present model of socially dominant life. It is the omnipresent affirmation of the choice already made in production and its corollary consumption. The Spectacle’s form and content are identically the total justification of the existing system’s conditions and goals. The Spectacle is also the permanent presence of this justification, since it occupies the main part of the time lived outside of modern production.

This passage makes it absolutely clear that Debord does not hold the idealist position that everything is an image, everything is a spectacle, but rather he sees the Spectacle as an integrated part of modern commodity production and consumption, a key part of the life-world of the masses, the ideological complement to the production of ‘real’ commodities.

However, today – much more than in Debord’s time – the formula in the proceeding sentence has to be modified, in the sense that an increasing number of commodities are themselves images that make up part of the Spectacle. Movies, magazines, online gaming, photography websites, websites of every kind, make up an increasing proportion of commodities.

Fashion is a typical example of this ‘image-isation’ of commodities. Hundreds of thousands of people, maybe millions, subscribe to fashion websites and buy fashion magazines. They know all the most famous models and brands and they watch the runway shows on Google. They may never buy any of the clothes on display (or even ever see them in real life), but that is not the point. The spectacle of fashion shows is its own point, creating its own dream, its own spectacular world. Fashion is, of course, a key part of the Spectacle in other ways, since the very essence of much of it is display, rather than demonstrating practical and comfortable clothes.

A point to which we return below is that not all images, even those created within the existing spectacularised media system, support the status quo or capitalist mystification. Arguably, the fact that the Vietnam War was the first television war de-mystified its genocidal brutality for millions. This experience explains why the US military was so keen to keep control of media reporting from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Dream World: images and mystification

There is an ambiguity and tension in Debord’s concept of the Spectacle: is the Spectacle the world of images, or is it sort of – everything? Steve Best and Douglas Kellner[5] comment:

Under this broader definition, the education system and the institutions of representative democracy, as well as the endless inventions of consumer gadgets, sports, media culture, and urban and suburban architecture and design are all integral components of the spectacular society. Schooling, for example, involves sports, fraternity and sorority rituals, bands and parades, and various public assemblies that indoctrinate individuals into dominant ideologies. The standard techniques of education which involve rote learning and mechanical memorisation of facts presented by droning teachers, to be regurgitated through multiple-choice exams, is very effective for killing creativity and choking the spirit and joy of learning. Currently, the use of video technologies in the classroom can reinforce this passivity and creates a spectacularisation and commodification of education, with TV ‘news’ punctuated with ads by corporate sponsors, such as the Whittle Corporation’s Channel One, which is made available in thousands of schools across the US. Of course, contemporary politics is also saturated with spectacles, ranging from daily ‘photo opportunities’ to highly orchestrated special events which dramatise state power, to TV ads and image management for predetermined candidate

Steve Best and Douglas Kellner[5]

I do not agree with this account, which tends towards the view that the Spectacle is sort of everything. It risks conflating the Spectacle with social practice in general. In Debord’s Comments on the Spectacle (1988), he distinguishes between the ‘concentrated spectacle’ and the ‘diffuse spectacle’. Roughly speaking, the concentrated is the highly centralised and controlled spectacle presented by totalitarian dictatorships, whereas the diffuse is typical of the popular culture of capitalist democracies. By 1988, Debord thought these two were becoming fused in an ‘integrated spectacle’ in which ‘the spectacle is mixed into all reality and irradiates it’. He thus speaks of a ‘judicial spectacle, a political spectacle, an education spectacle, and an entertainment spectacle’.

There is no doubt that aspects of the spectacular enter into all his examples, and the performances of Donald Trump (and Barrack Obama and other leading politicians for that matter) fit neatly into the concept of the Spectacle. But is everything that happens in a classroom or lecture theatre, or your front room, really part of the Spectacle? The tension in Debord’s account perhaps reflects a tension in reality. It would perhaps be better to say that although the Spectacle is centred on the world of images and commodities, and thus especially the mass media, advertising, and those elements of social life immediately affected by them, that is not the whole of social reality – and that of course leaves room for critique and resistance.

Celebrity culture

Celebrity culture is a key part of the Spectacle of modern capitalism, indeed in many ways its apex. Celebrities sell a spectaclar lifestyle, a dream-world that the masses can only gawp at, never attain. They sell numerous commodities, including the many images of themselves. Indeed, there are many celebrities who are merely famous for being famous – Kim Kardashian, Amber Rose, Stephen Baldwin, and Paris Hilton being notable examples.

Celebrities have a symbiotic relationship with mass media of course. Publicity is the life-blood of celebrity, but many parts of the media are completely dependent on celebrities for their existence. Magazines like Heat and Now! could not exist without celebrities. A whole genre of journalism is constructed around gossip columns in newspapers, and the ‘showbiz news’ slots which often consist of no more than press releases from celebrity publicists. Celebrity gossip, together with sport, is the staple diet of the popular press. Without celebrity, no Jonathan Ross Show or Graham Norton Show, no Strictly Come Dancing and no I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here! Celebrity culture is responsible for an army of publicists and stylists. It drives publicity in fashion, cosmetics, and fragrances. (Many celebrities have their own brands, and top celebs like David Beckham and Kim Kardashian have several). Most of all, celebrity is closely integrated with advertising.

Best and Kellner accurately explain the function of celebrity in the constitution of personal style and identity:

The philosophisation of reality, on the other hand, separates thought from action as it idealises and hypostatises the world of the spectacle. It converts direct experience into a spectacular and glittering universe of images and signs, where instead of constituting their own lives, individuals contemplate the glossy surfaces of the commodity world and adopt the psychology of a commodity self that defines itself through consumption and image, look and style, as derived from the world of the spectacle. Spectators of the spectacle also project themselves into a phantasmagoric fantasy-world of stars, celebrities, and stories, in which individuals compensate for unlived lives by identifying with sports heroes and events, movie and television celebrities, and the life-styles and scandals of the rich and infamous.

Individuals in the society of spectacle constitute themselves in terms of celebrity image, look, and style. Media celebrities are the icons and role models, the stuff of dreams who the dreamers of the spectacle emulate and adulate. But these are precisely the ideals of a consumer society whose models promote the accumulation of capital by defining personality in terms of image, forcing one into the clutches and clichés of the fashion, cosmetic, and style industries. Mesmerised by the spectacle, subjects move farther from their immediate emotional reality and desires, and closer to the domination of bureaucratically controlled consumption: ‘the more [one] contemplates the less he lives; the more he accepts recognising himself in the dominant images of need, the less he understands his own existence and his own desires … his own gestures are no longer his but those of another who represents them to him’ (Debord, Thesis 30). The world of the spectacle thus becomes the ‘real’ world of excitement, pleasure, and meaning, whereas everyday life is devalued and insignificant by contrast. Within the abstract society of the spectacle, the image thus becomes the highest form of commodity reification: ‘The spectacle is capital to such a degree of accumulation that it becomes an image’ (Thesis 34).

STEVE BEST AND DOUGLAS KELLNER

As we have discussed in previous articles, neoliberal capitalism overcomes its own inbuilt tendency towards depressing the consumption of the masses through debt. This is turn generates an inevitable cycle of crisis as the debt becomes unsustainable, as we saw in the 2008 financial crisis. The corollary of the debt mountain of the population at large is the cash mountain of the giant monopolists like Amazon, Google, and Apple. The only way to create productive investment outlets for the latter is a grotesque advertising splurge that infects everything.

The whole of the Spectacle is a giant advertisement for an ideal consumerist lifestyle that revolves around houses, cars, fashion, digital devices and content, health and fitness, and even foreign cultures to be sampled through lavish amounts of air travel. Even that poorer section of the working class that can barely participate in this idealised Spectacle lifestyle, can experience it gratuitously in digital content.

Debord and revolutionary strategy

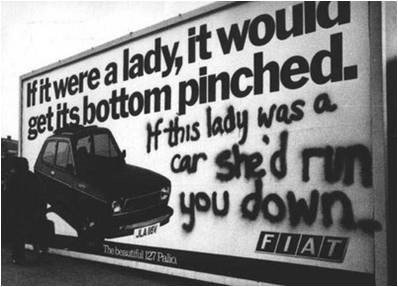

Guy Debord was central to the creation of the Situationist International, a tiny organisation which pursued a strategy of detournement (outflanking). Actually, it hardly ever did, because it was so small. Detournement meant creating situations in which capitalist meanings could be outflanked and exposed. This was mainly a cultural/propaganda activity, which could hardly be a political strategy for the workers’ movement or the movements of the oppressed – though it could be a component of such.

Arguably, the pre-eminent practitioner of detournement today is the graffiti artist Banksy. Whether portraying the grotesque or the mundane, he transforms images in order to make a critique of capitalist reality, typically using irony and ridicule. Whoever Banksy is, I doubt that he would claim that his detournement is a strategy for anti-capitalist struggle. But that is not the point – either of Banksy or Debord. The point is to unmask the Spectacle, to call it out, to alert people to the need to fight for a different way of seeing things and doing things – by introducing them to the ideas of socialism.

The Society of the Spectacle is a critique of the everyday life of the masses in late capitalism. But the most fundamental mass critique of consumerist everyday life has emerged in a way that might have surprised Debord – the environmentalist movement. Environmental politics point a dagger at the heart of the system that unites Apple computers with Zara fashion and Disney digital content. In the priorities of the environmentalist movement, the Spectacle has no place at all.

References

[1] Luke Haines, 1968 and All That,https://www.spectator.co.uk/2018/07/how-situationism-changed-history/

[2] https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/consumed-by-nights-fire

[3] https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/debord/society.htm

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lifeworld

[5] https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/Illumina%20Folder/kell17.htm