16 December 2020

Samuel Grove remembers an icon.

Genius turns back and forth on a contradiction.

To be called the ‘greatest footballer of all time’ is an accolade several orders of magnitude higher than any other sport, simply because so many more people play it. It’s the people’s game – the world over. To reach the level of semi-professional you have to be very, very good. To make it professionally you have to be exceptional. Anything higher than that and you start to run out of words. It’s why, when one player stands out above them all, it isn’t hyperbole to speak of a deity. It’s an entirely rational response to a phenomenon that defies description.

The difficulty of succeeding in football is, in part, concealed by the fact so many more people can play it. Unlike say basketball, rugby or athletics, your success or failure doesn’t hinge upon your physical prowess. The variety of physiques in world football is almost as varied as the population at large. It allows anyone, even a diminutive malnourished boy from the barrios of Lanús, to dream of playing in and winning a World Cup.

Every boy dreams of winning a World Cup, but what must it be like to be the subject of every boy’s dreams?

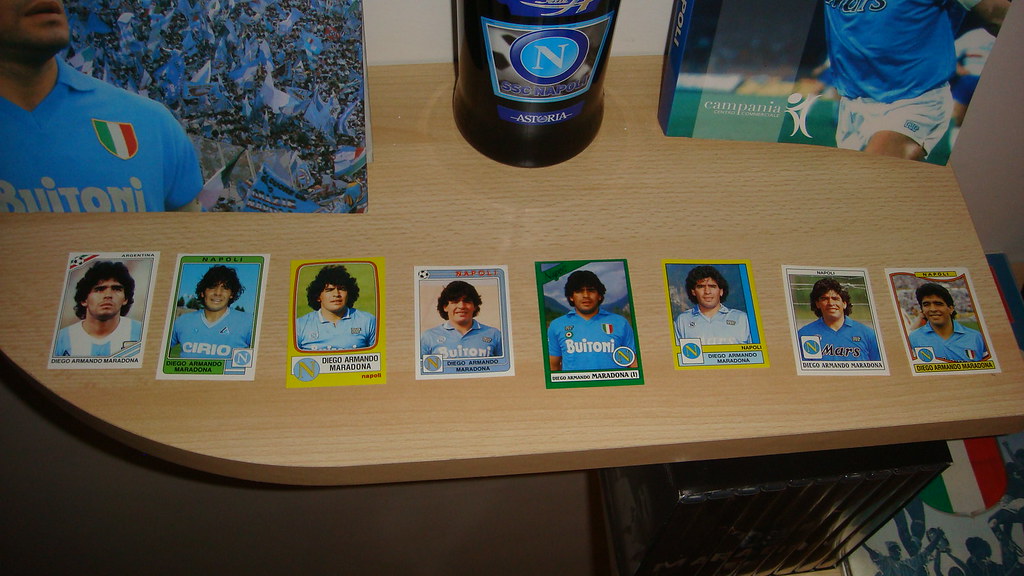

Diego Maradona was touted for greatness from a very early age. From the age of eight he was entertaining crowds with his ball skills. By 11 he was being covered by the national press. At 15 he made his debut in Argentina’s Primera División. At 16 he made his debut for la Selección (the Argentina national team). By the age of 19, and having never played club football outside his native country, even the notoriously sullen British press were comparing him to Pelé.

Maradona was, in fact, supremely physically gifted, but in ways that weren’t obvious. Being small confers an advantage in football: the low centre of gravity makes you difficult to knock off the ball. Maradona’s balance was such that he could move in any direction. A ‘Maradona Challenge’ video in which you had to guess which direction he would go with the ball went viral a few years ago because of its notorious difficulty. His teammates described his visual system as panoramic – seeing things in his periphery with the acuity and detail as if they were right in front of him. Much would later be made of his ‘hand of God’, especially by those wishing to dismiss him as a cheat. Hand of God was indeed the appropriate term but not in the way he described and the way his detractors understood. Maradona could rotate his ankles 360°. He literally had hands for feet.

These were fragile gifts. Upon seeing Holbein’s The Body of the Dead Christ, Dostoevsky wondered whether Jesus’s disciples would still have believed in his godliness supposing they’d seen his tortured, mangled, bleeding body. Maradona’s opponents were under no illusions regarding his mortality. He grew up in the one of the most violent leagues in the world. He was kicked out of the 1982 World Cup: in the game against Italy alone he was fouled 23 times. And those were just the fouls that were given. Against Brazil he was kicked up and down the pitch, including in the penalty area, until the referee finally decided to intervene, sending Maradona off for retaliation. There was no let-up in Spain when he signed for Barcelona. He was butchered in Bilbao. Andoni Goikoetxea broke both his ankles and put the boots he did it with behind glass as a monument to his achievement. Maradona was carried away in a blanket, driven to a hospital in a borrowed van and consoled by the hospital cleaner.

Club owners had little concern for his welfare. Having almost bankrupted themselves signing Maradona in 1981, Boca Juniors threw him into extra games to recoup the funds. When he wasn’t fit to play, they injected him with anaesthetics and anti-inflammatories and sent him out anyway. The injections continued throughout his career. As the recent documentary about his time in Napoli revealed, Maradona had to have weekly injections in his back just so he could walk, never mind play football.

This is why it’s difficult to take complaints about Maradona’s cheating seriously; complaints that, for obvious reasons, reverberate most loudly in England. As Chinua Achebe pointed out, the famous English fidelity to rules derives from the fact that we wrote them and did so to suit ourselves. England invented the rules of football, but in a way to mimic our favourite pastime of war rather than to create the beautiful game. The conflictual nature of football would be on display when Maradona first faced England in 1980. Bad luck would prevent him punishing England in the same way Ferenc Puskás had 27 years earlier. But England were also wise to the newly crowned South American footballer of the year. Watch the highlights. Watch the ‘late’ challenges . Then recall that Maradona was only 19 and this was supposed to be a ‘friendly’.

The match between the two sides six years later was anything but a friendly. A quarter-final of a World Cup and four years on from a war between the two countries over an island that Argentina believed was rightfully theirs, whilst Britain’s colonial history said otherwise. Gangs from both countries travelled to Mexico to fight outside the stadium, which continued in the stadium long after the game had started. England, at least, were determined to bring this violence onto the pitch. Within 10 minutes Terry Fenwick had aimed a tackle at Maradona’s midriff. A few minutes after that he elbowed him in the face. Everybody knows what happened next, but this background provides the correct context for understanding why the match has such resonance for people not just in Argentina, but all across Latin America and beyond. For people of the Global South, both goals, in different ways, resemble less divine intervention from on high than a subaltern rebellion from below.

The first goal. It wasn’t just that he punched the ball into the net. It was that he celebrated by shaking the offending hand in the air. It was that immediately after the match he refused the invitation to apologise, calling it instead ‘the hand of God’. It was that he has taken every opportunity since to rejoice in his trickery. Interviewed in a recent BBC documentary, he described how he ‘pickpocketed the English’ before descending into a belly laugh. Elsewhere he has boasted that it ‘was payback for Las Malvinas’ and quoted the old Spanish proverb that ‘Whoever robs a thief gets a 100-year pardon’.

The second goal. A solo run is the most beautiful thing you can watch on a football field, but they are often quite brutal affairs. Lionel Messi is often compared to Maradona, and rightfully spoken of in the same breath. Close-ups of his solo goals reveal the sheer force required to power through three or four defenders on your way to scoring. Closer views of Maradona’s ‘goal of the century’ reveal it to be even more ethereal, more other worldly, than it did from afar. Watching from this angle it doesn’t even look like the goal at all, but rather a balletic reconstruction of it.

When Maradona scored he snapped back into being one of us. He celebrated goals, the goals he scored, even his greatest goals, with the ecstasy and excitement of a fan. However singular his talent, however single-handedly he made and scored his goals, he would reunite with the collective – teammates and supporters – to embrace their shared joy. His greatest moments felt as much ours as they were his.

Maradona followed his two goals against England with an equally sublime performance against Belgium in the semi-final; a performance that included another of the World Cup’s great goals. In the final he would provide the assist for Jorge Burruchaga that would win Argentina the World Cup. In all Maradona made or scored ten of Argentina’s 14 goals in the tournament, a feat no player has come close to since. It was for good reason that he is credited with winning the World Cup on his own.

More trophies would follow but none met the celestial heights of Mexico ‘86. In 1990, Argentina managed to stumble their way to the final largely thanks to the efforts of their substitute goalkeeper Sergio Goycochea. But for a solo run that did for early favourites Brazil, their captain was basically hobbled on one leg. Four years after that, Maradona only managed one game before being sent home from the 1994 World Cup in disgrace after failing a drugs test.

Maradona’s use of drugs is but one of the reasons he provokes a fair deal of ire and judgement. Other more understandable reasons include allegations of domestic violence and refusing to recognise his son. I don’t ask for him to be given a pass for any of these things – only that his sins be viewed in context. Maradona was born into less than heavenly circumstances. That much is uncontroversial. But from the moment he left those circumstances his life was no longer his own. He belonged to higher, more powerful forces. To clubs that considered him a cash cow and a piece of meat. To the media that considered him journalistic fodder for flogging stories. In Napoli he was preyed upon by the Camorra who regarded him as a fashion accessory. Above all he belonged to a public hell-bent on treating him as a messiah. As his teammate Jorge Valdano would write, ‘we worshipped him pitilessly.’

It was probably these experiences that made Maradona sympathetic to the plight of the underdog and, in later years, would orient him to left politics. He became good friends with Fidel Castro, Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales. In 2005, he joined the protests in Mar del Plata against George Bush, declaring ‘La Argentina es digna, echemos a Bush’ (‘Argentina has dignity, expel Bush’). He proudly expressed his solidarity with the Palestinians and other oppressed people around the globe. His internationalism has spawned comparisons with Muhammad Ali – the only other sports personality of the 20th century to have achieved the kind of worldwide fame and adulation of Maradona. Ali had sacrificed his heavyweight title and sporting peak in refusing to fight in Vietnam. Maradona could claim no such grace, but in truth Ali’s time as a radical was short. Within a few years, he would be embraced by Republican presidents and advertising retirement pensions. There is none such a poison as flattery.

Maradona, to his abundant credit, carried on pissing off exactly the right kind of people. During his career he spoke of the corruption and criminality of FIFA. At the time it seemed like a conspiracy theory. Turned out he was right. FIFA’s bitterness towards him was such that when he won the public vote in 2000 to decide the FIFA Player of the Century, FIFA promptly abandoned the poll and appointed a committee of jurors instead who awarded it to Pelé. Maradona was suitably incensed. The award, he said, ‘isn’t worth shit’.

Maradona’s preparedness to go to the gutter did not always cover him in glory. In another spat with Pelé he mocked him for having lost his virginity to a man. Other times his vulgarity wasn’t so reprehensible. In a famous press conference on the eve of the 2010 World Cup, he told an ensemble of corporate journalists that had spent the previous months savaging him to ‘suck it’. He continued:

‘I am either white or black. I will never be grey in my life. You treated me as you did. Now keep on sucking it. I am grateful to my players and to the Argentinian people.’

I think there is something commendable here that goes beyond fierce loyalty—as admirable as that is. We live in an age where everyone, even much of the political left, prefers the mealy-mouthed diplomacy proffered by public relations firms. Where political correctness is often deployed in ways positively dripping with sanctimony and snobbery. Maradona never pretended to be better than he was, nor did he ever abandon the ‘airs and graces’ of where he was from. At the core of such honesty lies the appeal for us to afford him the same courtesy. ‘Speak of me as I am / nothing extenuate’.

Maradona was, as Eduardo Galeano would say, the most human of the Gods.

Samuel Grove has been a political activist in the UK for the last 15 years and a Labour activist for the last 5. His previous writing has been published in Tribune, Salvage, Monthly Review, Alborada, and Red Pepper. He is writing a book on Charles Darwin coming out next year with Lexington Books.