‘Today Rhodes University is proud to honour one of the English-speaking world’s foremost public intellectuals . . . historian, novelist, playwright, filmmaker, activist; an incisive, often witty, political commentator; determined champion of oppressed, marginalised peoples across the globe . . . Mr Chancellor, I have the honour to request you to confer on Tariq Ali the degree of Doctor of Laws, honoris causa.’ (p 638)

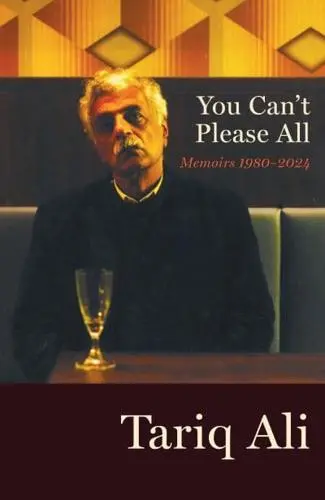

Never falsely modest, Tariq Ali manages to include his honorary doctorate conferred by Rhodes University in South Africa in his 800 page book of memoirs.

Certainly there is a lot of truth in this pen portrait. He was and is a man of many talents. For a time he was a leading member of the International Marxist Group and of the Fourth International, a heritage some of us in ACR share. His work with the Bandung File on Channel 4 was really innovative, bringing previously unheard voices and stories on mainstream national TV. In collaboration with Howard Brenton he wrote Moscow Gold for a National Theatre production on the Gorbachev period. Through the very readable Islamic Quintet of historical novels, he introduces us to the rich culture of the Arab Empire.

He has regularly written books of political analysis, and is particularly strong on South Asia, Afghanistan, Iraq and global politics. He has even found time to write a provocative debunking of Churchill’s life and crimes.

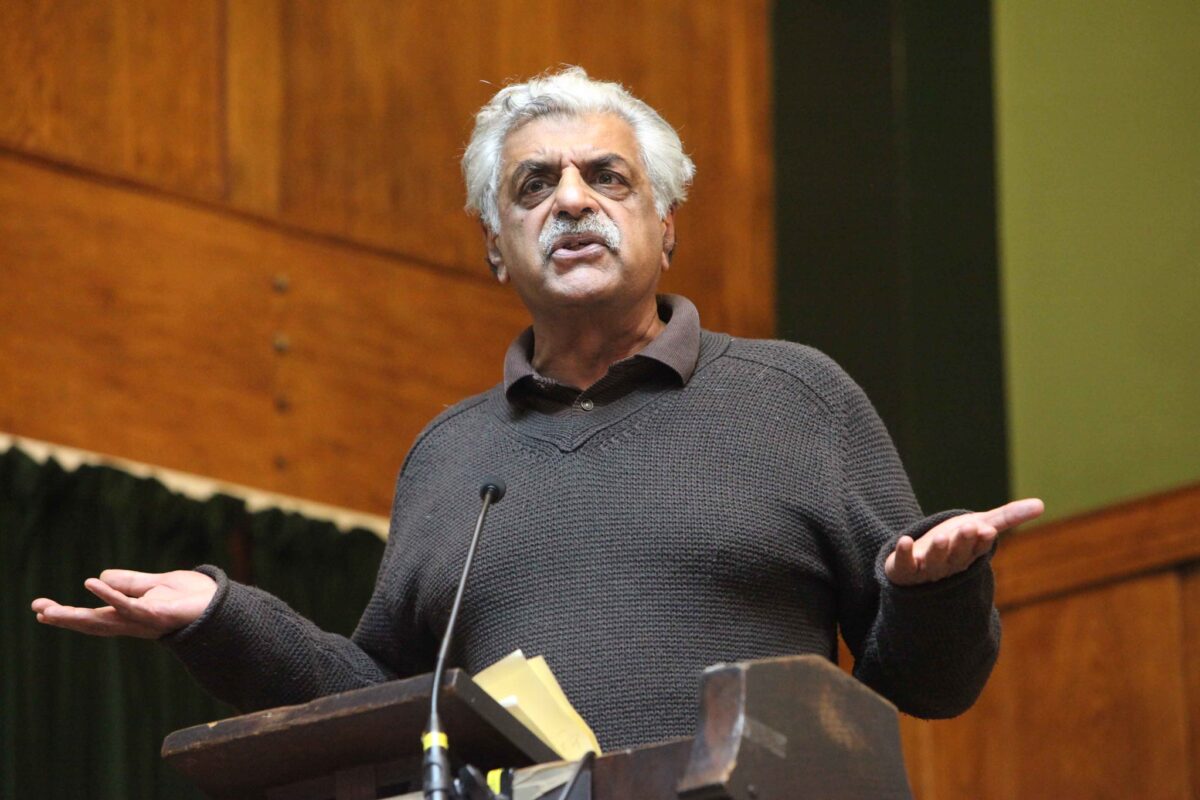

Tariq has been a key member of the New Left Review, a prestigious Marxist magazine that has been a resource for the left and for academia. Throughout his life he has spoken up for the oppressed and is still a much anticipated speaker at demonstrations and meetings – most recently in solidarity with Palestine. His main contribution today is promoting a well-argued but virulent opposition to US imperialism and its allies such as Israel or Starmer’s Labour government.

An inspirational comrade

Before discussing any political differences we have with him on the situation in Ukraine, Syria and the notion of anti-imperialist camps we need to acknowledge his positive lifetime commitment to the left.

Is it such a bad thing that a public Marxist intellectual receives some national recognition by the media? He has appeared on Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs. The British media of course very rarely invites people from anyone to the left of Labour on its main news or current affairs shows.

Tariq has inspired many people to get involved in politics. I remember seeing him speak at Essex University in the early 1970s. At one stage a Maoist threw a tomato at him from the balcony and he calmly picked it up and took a bite. Not only was he a fluent speaker working without notes but he was quick witted in debate or to respond to hecklers.

The Socialist Workers Party (International Socialists at that time) may have been a bigger outfit than the IMG but we had Tariq with all those international connections – invited by the Vietnamese liberation fighters or debating with Kissinger. He was mates with John Lennon and Yoko Ono too. He was the opposite of the boring old style trots who tried to look like workers with their donkey jackets and spouted wooden propaganda.

I remember during his time editing the Socialist Challenge weekly he managed to work text from Lewis Carroll into some article or other. Its elegance and wit impressed me. In the book he also recounts his role in the Southall events where the South Asian community fought back against the fascists of the National Front in 1979. He was well known and respected in South Asian communities. He was correctly seen as a threat to the British state and he gives some details of the numerous MI5 and special branch reports and of his continuous surveillance by the authorities. Typically, he wishes that he could get hold of the transcripts of the regular conversations he had with fellow Marxist and comrade, Robin Blackburn. He thinks they would make a good book.

Great connections

The book gives a lot of detail about his family who were part of the Pakistani political and media elite – albeit on the left. Tariq was close to the Bhuttos and the Gandhi dynasty. He was friendly with Imran Khan too. In fact right through his life he has maintained connections with the political class on a global basis. Being at Oxford meant he knows Tory and Labour politicians. His role in the media and anti-imperialist movements means that when progressives actually formed governments he had these ministers’ or ambassadors’ numbers in his address book. At one stage he was offered the job of leading TeleSur, a TV project of Chavez’s progressive Venezuelan regime. Nobody on the British left has had this sort of international profile. At one time during the activity against the illegal Iraq war he was receiving dozens of invites to speak in different countries every month. His books are published in many countries and New Left Review also has a global reach which helps maintain this profile.

You Can’t Please All is a huge compendium of analyses, gossip, anecdotes and memories of himself and other comrades and friends. It is not narrowly political. You can find articles about cricket as well as his visit to North Korea where they invited Red Mole to print the “Great Leader’s” writings. I liked his essay opposing the Royal Family. There is lots of detail about the Bandung File, Channel Four’s ground breaking initiative. It promoted news and culture from the Black and Asian community. Sadly it or something similar has struggled to survive.

A campist?

The battle over the future of New Left Review is presented and this provides details that have not emerged before. People like Quentin Hoare were accused of going soft on imperialism in relation to the Balkan situation. Whether this is true or not it does launch a thread of Tariq’s thinking that suggests a preoccupation with the blowback created by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the supremacy of US imperialism.

“The two principal ideas of the New Order were: (a) the new model capitalism as the sole way of organising humankind from now on till the planet imploded, and (b) the West’s right to flagrantly violate national sovereignty in the name of imposing its own brand of ‘human rights’”. (p 377)

The problem with this analysis is that Ukraine shows that it is not just the West that flagrantly violates national sovereignty, since Putin has invaded a country whose national existence he denies. In fact Tariq was so convinced of a uni-polar war dominated by US imperialism that he refused to countenance the possibility of a Russian invasion. Right up to the last weeks he completely downplayed the idea that Putin would march on Ukraine. To his credit, he does accept that he got that wrong. But he persists in seeing the war mainly as a proxy war and refuses to clearly support Ukraine’s right to self-determination and to resist. What a contrast with his immediate understanding of the Russian invasion and occupation of Afghanistan in 1979!

I still remember an international meeting of the Fourth International in 1980 where he argued clearly and correctly for a Russian Troops out position. Some of the leadership at the time, for example Livio Maitan, did not share Tariq’s position.

On Syria too he has written in Sidecar (the NLR news magazine) that the overthrow of Assad is a “huge defeat for the Arab world”. He only sees the threat of an Islamist takeover and refuses to see that is only one possibility and that the current situation gives some hope and space for a different outcome.

His article in the book on Palestine from 2004 (page 416) has stood the test of time. He correctly highlights how the bankrupt, corrupt secular leadership of the PLO has led to the rise of the Islamist Hamas which he defends as a resistance but is not the leadership the Palestinians need.

Leaving the Fourth International

The chapter on why he left the Fourth International (FI) is interesting to me not just because we lived through it but also what it says about Tariq’s later trajectory. He says the FI refused to recognise that the end of the Portuguese revolution in the late 1970s meant that the rise of the revolutionary left and radical struggles was over in Europe. Working with the resurgent Bennite currents in Labour was the way forward.

At the same time, he thought that one response of the FI to the new situation – the turn to industry – was a big mistake. The turn was about sending members into skilled manual jobs in industry or transport. Some were students. This had some negative effects on the trade union fractions that had previously been developed in the public sector with some success. The turn to industry was a response to a real problem – the new parties were not embedded enough in the core sectors of the working class. Given the reality that the upsurge of radicalism was dimming then this was even more important.

However there were mistakes made and the balance sheet was mixed. A group in Britain who had gone into the British Leyland factory were exposed and it caused national headlines. The fraction later built up on British Rail and the Underground had greater success. At the same time the IMG made a turn to working in Labour a year or so later.

In any case, Tariq himself did not manage to integrate the Labour Party and from then on was not involved in building a revolutionary organisation. In other words his split was not just about an assessment of the situation – the big miners’ strike was still to come anyway – or a tactical turn but about the very idea of building a revolutionary Marxist party. If you look through the whole book there is no discussion of this aspect of revolutionary strategy, particularly in Britain.

There is a revealing comment about calling Ernest Mandel (an FI leader) and finding he was preoccupied with the minutiae of some internal differences in one of the FI sections. Tariq’s reaction was, what a waste of time. I suppose this shows is the difference between being an organic intellectual of the class, where the question of building a political organised alternative is ever present, and being a Marxist intellectual who is publicly known but who does not participate at that level at all.

To give a contrary example, one of Tariq’s friends was Daniel Bensaid, who was a brilliant Marxist, recognised in academia and who wrote a lot of books. He never stopped being involved in the everyday business of building revolutionary parties either in France or Latin America.

Intellectuals and the Party

It will always be a challenge for small revolutionary parties to hold on to the intellectuals or personalities they attract. Even sustaining a fellow traveller relationship is positive but difficult. This does not mean in any way that Tariq’s ongoing contribution should be undervalued or dismissed.

The book is a great read and as a compendium you can dip in or out of it according to your interests. It is like being invited to dinner with him and who would turn down such an invitation? The book cover picture suggests this and the book is spiced with tales of good food, wine and discussion across the world. Radicals and activists need to relax, enjoy the good things of life and have fun. Even if you disagree with some of his analyses, Tariq has always got something insightful and interesting to say.

I congratulate David Kellaway for writing a very good review.

Thanks I tried to be balanced. Took time to write since a bit personal too

Anything aboutthe struggle For Troops out In the North of Ireland

Excellent review Dave. I am in broad agreement with your point of view.

Very informative critique–many things I didn’t know, not being in England or involved in leadership of any FI groups. Here is my take on the book, in the context of three author left-wing autobiographies: https://againstthecurrent.org/lions-in-winter-longtime-activist-lifes-on-the-left/

As Dave points out Tariq’s relationship with the FI ended decades ago, and his renown is not limited to Britain. Reading New Left Review or the myriad of other interviews/articles/books available lets you know where Tariq stands today.