Long-Read Theoretical Discussion Article

This paper offers a summary of new Marxist thinking about the nature of the crisis and what must be done to turn mass protest into the revolutionary transformation on which our survival depends.

Neil Faulkner is the joint author of Creeping Fascism: what it is and how to fight it and System Crash: an activist guide to the coming democratic revolution. He works closely with a small group of theoretical collaborators and draws heavily on their insights in this essay, but takes full responsibility for its content.

Billy (Dennis Hopper): We can’t even get into a second-rate hotel. I mean a second-rate motel, dig. They think we’d cut their throat. They’re scared.

*

George (Jack Nicholson): They’re not scared of you. They’re scared of what you represent to them.

*

Billy: All we represent to them is somebody who needs a haircut.

*

George: Oh, no. What you represent to them is freedom. Freedom’s what it’s all about. Oh yeah, that’s right. That’s what it’s all about. But talking about it and being it, that’s two different things. It’s real hard to be free when you are bought and sold in the marketplace. Don’t tell anybody that they’re not free, because they’ll get busy, killing and maiming to prove to you that they are. They’re going to talk to and talk to you about individual freedom. But they see a free individual, it’s going to scare them. Well, it doesn’t make them running scared. It makes them dangerous.

*

EASY RIDER 1969

Prologue:

The Wall

1.

The Wall now spanned the globe. It comprised ten billion screens. Little ones, personal ones, carried in pocket or bag, to be sprung into use any spare minute, every spare minute. Big ones, able to fill a stadium with light and sound, watched by tens of thousands at a time. And all sorts of medium ones in between, laptops, X-boxes, big-screen TVs, cinema screens, and the like.

Ten billion screens. Click. Billions of images to choose from. Click. Available 24/7. Click. Whatever you want, wherever you want, whenever you want, instantly, on demand. Click.

The 7.5 billion spectators gawping at the Wall were not so much watching it as being mesmerised by it. The Wall was a tranquiliser. The spectators were already semi-comatose, otherwise they would have been doing something else, not just gawping and clicking. But once it had their attention, the Wall held them fast. It became an addiction. They couldn’t drag themselves away, couldn’t stop gawping and clicking. They were hooked by the eternal search for the spectacle – another spectacle, the next spectacle, a bigger and better spectacle, an as-yet-undiscovered spectacle.

A moment’s distraction from the Wall and the gnawing FOMO began. How long before the next fix?

Always back to the Wall. Before it, an ocean of blank faces and inert bodies uploading spectacles into vacant brains, more and more of them, forever and ever. Until the Wall had sucked out all that remained of the life force, extinguishing mind, will, activity, freedom, reducing the spectators to husks.

2.

Marx and Engels explained how the dominant ideas in every epoch are the ideas of the ruling class, because the ruling class controls the means of production and the state, and therefore the social superstructure, and therefore the primary systems of communication, socialisation, and indoctrination – churches, schools, press, etc.

But they also argued that ideas were formed and consolidated in a more profound way. They distinguished between appearance and essence – how individuals experienced life in an everyday sense as opposed to how that experience was actually created by hidden forces. Marx’s most famous example concerned labour for capital. Workers appeared to enter into a free contract with the capitalist, selling their labour-power in return for a wage that represented ‘a fair day’s work for a fair day’s wage’. But in fact, the employment contract obscured an unequal exchange, for the worker, lacking both means of production and means of subsistence of her own, was compelled to sell her labour-power to the capitalist; and the capitalist would employ her only on condition that the value of the labour she performed both covered her wages and yielded a surplus/profit over and above that.

Nor was this, for the capitalist, a matter of choice: he was compelled, under the whip of competition, to exploit workers in order to keep costs and prices down, to accumulate a surplus fund, to invest in more advanced techniques, to raise productivity and output; if he did not do this, he was liable to be priced out of the market by more dynamic rivals. The capitalist was, therefore, a ‘personification of capital’ – a living embodiment of the imperative to exploit and accumulate.

In these and other ways, social relationships between human-beings became ‘thing-like’. Instead of human-beings entering freely into collective processes of creative labour, their activity was determined by forces – capital accumulation, commodity exchange, the market – outside their control. Marx used the term reification to describe this thing-like character of human relationships under capitalism.

The essence of humanity as a species is that we engage in conscious, collective, collaborative, creative labour, both in production and reproduction: we are social animals. Reification therefore involves an existential rupture in humanity’s species-being. Marx used the term alienation to describe this rupture. Human-beings are alienated from nature, from each other, from the labour process, from the products of their labour, from their species-being, because of the reified character of social relations under capitalism.

The Wall is an extreme expression of alienation.

3.

Antonio Gramsci paid particular attention to the systems of communication, socialisation, and indoctrination by which capitalist social relations were obscured, legitimised, and sustained. He underlined the distinction between active coercion (by state repression) and passive consent (by means of socialisation, indoctrination, etc) in suppressing resistance to the system.

He saw the dominant ideas of the ruling class as a pervasive ideological hegemony that penetrated the whole of civil society – state, media, school, church, neighbourhood, family, etc – reaching into all the nooks and crannies of everyday life. He was struck by the way – in contrast to more obviously coercive social orders like Tsarist Russia – in which modern, developed, liberal-parliamentary democracies acquired multi-layered ideological defences against revolution from below.

This included the bureaucratised, routinised, reformist character of most working-class organisations – trade unions and socialist parties – where a layer of full-time functionaries operated to mediate between capital and labour, to contain popular revolt, to accommodate demands from below to the imperatives of the system. They became personifications of the prevailing ideological hegemony inside the labour movement. They became labour lieutenants of capital.

The Wall, the most powerful communications system in history, is a superlative mechanism for transmitting the hegemonic ideas of the ruling class, sedating social discontent, suffocating dissent, achieving consent.

4.

The Frankfurt School was also much concerned with capitalism’s mechanisms for achieving legitimation and consent, and, more broadly, for tranquilising and pacifying a potentially rebellious working class. In particular, in One-Dimensional Man (1964), Herbert Marcuse argued that advanced (post-war) industrialism had created an affluent consumer society in which false needs were created by mass media, the sales effort, popular culture, etc. Satisfaction of these needs through the consumption of commodities became a substitute for human happiness, but also a realm of unfreedom and social control which shrivelled the space for critical thought and action.

Marcuse (and others) elevated the commodity to a new theoretical level. Marx had stressed the contradictory combination of use-value and exchange-value in the capitalist commodity. On the one hand, the commodity corresponded to a real human need; on the other, it represented an objectified form of labour to be sold for profit. Marcuse, on the other hand, emphasised the rising proportion of commodities which lacked any real use-value, which in fact corresponded to artificially generated false needs.

Capital benefitted in two senses. On the one hand, false needs created a growing market for consumer goods and therefore expanded capital accumulation. On the other, the satisfaction of false needs legitimised the system and pacified the working class; it fostered a world of atomised individual consumption, a retreat from the collective and creative into a realm of false consciousness and private unfulfillment and unfreedom.

False needs created a second layer of alienation. In Marx’s conception, the worker is alienated from the use-values created by her labour. In Marcuse’s conception, the worker is often conned into consuming commodities devoid of any real use-value at all.

But the Wall represents yet another layer of alienation.

5.

In The Society of the Spectacle (1967), Guy Debord argued that the world of the real – real things and real activities – had been replaced by a world of mere representations or spectacles. Life was no longer lived, it was merely depicted. Humans were no longer active creators of a real material world, but passive spectators of a constructed world of images.

Some of Debord’s formulations were exaggerated. Human-beings are organic life-forms. They have a material existence and therefore material needs. We cannot be reduced to consumers of spectacles.

But, like Marcuse, Debord offered a profound insight into the deepening alienation characteristic of late capitalism. Where Marcuse had emphasised false needs, commodification, the consumer society, Debord highlighted the role of representation, images, spectacles in the context of growing atomisation, privatisation, and passivity.

Debord anticipated the Wall – a virtual Wall formed of billions of screens projecting billions of spectacles. Here, alienation acquires a third layer, where false needs take the form not of actual commodities but of representations of commodities, as aspirations, hopes, yearnings, neuroses, fantasies are sucked into a vortex of electronic spectacles.

6.

The Wall is a product of the Third Industrial Revolution.

Coal, steel, and steam-power were the basis of the First Industrial Revolution; the railway was the supreme symbol of the age. Oil, electricity, and motorisation were the basis of the Second Industrial Revolution; motor vehicles and consumer durables were obvious symbols. Computers, digitalisation, and instant electronic communication have been the basis of the Third Industrial Revolution; this is the age of the smartphone, tablet, and laptop.

Increasing velocity characterises each revolution. The faster goods and services can be produced, distributed, and exchanged, the quicker the money can be turned over. Money works by moving. The quicker it moves, the more it can do. The faster it turns over, the sooner it can be reinvested. The higher the velocity of money, the more rapid the accumulation of capital.

The Third Industrial Revolution has made capital in its money form weightless. It can defy the law of gravity and move faster than the speed of light. It can move from one side of the world to the other at click-button speed.

The increasing velocity of capitalism’s industrial revolutions affects all aspects of social life. Before 1800, information moved at the speed of sailing ships and horse-drawn carriages. By 1875, it moved at the speed of steamships, railways, and telegraphs. By 1950, at the speed of the telephone and the radio.

But the communications technologies of the First and Second Industrial Revolutions were not bulk carriers; they could handle only small cargoes of information. To carry bulk it was necessary to digitalise and miniaturise data. This was the central technological achievement of the Third Industrial Revolution.

The Wall is a product of the digitalisation and miniaturisation of data.

The First Industrial Revolution separated human-beings from their means of production and subsistence; it imposed the primary alienation.

The Second Industrial Revolution, in order to sustain exponentially expanding capital accumulation, and also to sedate a growing and potentially rebellious working class, created false needs; this was the second alienation, where privatised consumption of commodities with little or no use-value became an opiate to compensate for loss of the collective and the creative.

The Third Industrial Revolution has transformed false needs for material commodities into false needs for virtual commodities, for electronic images, for representations and spectacles. This is the third alienation.

We can conceptualise the Wall in economic-technological terms as a product of the Third Industrial Revolution, and in social-anthropological terms as the primary expression of the third alienation.

Capitalism first alienated human-beings from nature, their means of production, and their means of subsistence. It then alienated them from their real needs by substituting false needs. It has now alienated them from the material world of things by creating a virtual world of spectacles.

First we made things. Then we only consumed things. Now we merely observe things. From producer to consumer to spectator: this is the anthropological history of human alienation under the domination of capital.

Introduction

1.

An inpatient undergoing tests and treatment, I was taken in a wheelchair from the cancer ward on the 13th floor of University College London Hospital’s tower down to the scanning department. Coming round a corner, I saw the waiting room on the right. About 15 people were sitting in chairs staring at two huge screens on the far wall. I was pushed down to the end of the front row of seats, close to the screens.

The screens, ranged side-by-side, were both showing the same image. Why two? The sound was turned up loud. A blizzard of light and sound delivering a daytime TV game show called Bargain Hunters. It was impossible to talk or read or think or rest. There was only the game show.

Everyone seemed to be staring blankly at the screens. I thought of the scene in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange where Malcolm McDowall’s eyes are pinned open in front of a cinema screen so that he can be indoctrinated by being forced to view graphic images of violence. Here, in an NHS waiting room, was the society of the spectacle in microcosm.

2.

The inspiration for this essay is my realisation that the whole of mainstream politics has now become part of the spectacle. To some degree, politics has always involved spectacle. The burial of a pharaoh, the crowning of a king, the holding of a party rally: all spectacles. But an accretion of quantitative changes eventually tips into qualitative change, into a new state of being. So it is now with the politics of the system – mainstream politics, bourgeois politics, capitalist politics. Much is still said about substantive issues (though less and less); but nothing is ever done to address any of them.

Bourgeois politics has become form without substance, performance without action, spectacle without meaning. It has become a façade of images where the representation has no referent, no relationship with anything concrete, material, practical. There is only spin. A kaleidoscope of spectacles projected onto the Wall, signifying nothing.

3.

We have entered the greatest crisis in human history. We are experiencing an ecological and social crisis, driven by exponential capital accumulation, whose end result will be the extinction of human civilisation.

Bourgeois politics has been reduced to spectacle because no effective action is possible in the context of exponential capital accumulation. All effective action requires negating the imperatives of capital accumulation. None can be taken without dispossessing the rich and disempowering the corporations; that is, without an international revolution of the workers, the oppressed, and the poor; without mass participatory democracy from below; without a red-green transformation based on popular power; without a restoration of the commons, the collective, and the creative; without a comprehensive transcendence of human alienation.

Piecemeal reform cannot save us. Only a new social order based on the negation of capital accumulation can save us. Therefore, bourgeois politics, embedded in the existing social order, has been reduced to a façade of spectacles.

4.

This essay is, in a sense, a concise theoretical history of accelerating and potentially catastrophic human alienation. It charts a process of reification in which human-beings lose control over the products of their own labour and the forces unleashed by their collective creativity. It analyses the ever-more unlimited domination of a self-feeding engine of blind, anarchic, exponential growth: the process of capital accumulation encapsulated in Marx’s famous formula, M – C – M+, where M is the money capital originally invested, C is its transformation into energy, machinery, labour, and raw materials, and M+ is its return to the money form with an increment (surplus/profit). A process whose only purpose is to renew to cycle – forever and ever, until the end of time, until complete ecological and social breakdown and the extinction of human civilisation.

In Chapter 1, Stasis, I analyse the multi-dimensional character of the world crisis and our rapid acceleration towards comprehensive ecological and social breakdown and the extinction of human civilisation. In Chapter 2, Spectacle, I contrast this with the multi-layered alienation that has atomised human society, tranquillised discontent, and smothered critical thought; a pandemic of mass cognitive dissonance and stupefaction in the face of system collapse.

In Chapter 3, Creeping Fascism and Global Police State, I summarise arguments advanced elsewhere about the global shift to reaction and repression, now rehearsed in the context of the accelerating crisis of reification and alienation that is my main focus here. Chapter 4, Corporate Power and Capital Accumulation, is also a recapitulation of arguments advanced elsewhere; but arguments are essential to repeat here, for the engine of the entire crisis is the process of exponential capital accumulation.

Chapters 5, 6, and 7 concern a possible alternative future: instead of accelerating ecological and social breakdown, intensifying and paralysing mass alienation, and rapid advance towards extinction under the rule of capital, the greatest revolutionary recasting of global society in human history. I discuss this in relation to three overarching concepts.

Chapter 5, The Commons, concerns the transcendence of the primary alienation – the rupture separating human-beings from nature, from one another, from the labour process and its products, from their means of production and means of subsistence, from their very species-being. Because humans are social animals defined by conscious, cooperative, creative labour, the restoration of the commons – usurped by capital – is perhaps the best description of this process.

This necessity – the existential imperative of the restoration of the commons if we are to prevent extinction – immediately raises the question of revolutionary agency. Chapter 6, The Democracy, posits the existence of a third titan of power alongside the global police state discussed in Chapter 3 and the corporate capital discussed in Chapter 4. I call it the democracy. This has nothing to do with the veneers of spin and spectacle to which liberal-parliamentary bourgeois democracy has been reduced. It refers to the potentially transformative power of the overwhelming majority of humanity – the workers, the oppressed, and the poor – if organised in a global movement of revolution from below and popular self-emancipation.

Chapter 7, Revolution from Below, draws upon both historical and contemporary examples to discuss the possible concrete forms that democracy may take in the struggle to overthrow the rule of capital and save the planet and human civilisation in the short time remaining

Though most of my examples are drawn from British experience – which I know best – my theoretical generalisations concern world capitalism as a whole.

5.

This analysis does not belong to any existing Marxist tradition. It is a synthesis drawing on a wide range of traditions. As well as being influenced in my thinking by most of the classical Marxist theoristss – notably, Marx, Engels, Lenin, Trotsky, and Gramsci – I have also absorbed insights from, amongst others, the economic theories of Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy, from the radical Freudian psychoanalysis of Sandor Ferenczi, Otto Rank, Wilhelm Reich, and Erich Fromm, from the Frankfurt School, especially the work of Herbert Marcuse, from the Situationist perspectives of Guy Debord, from the Fourth International tradition of Ernest Mandel, and from the International Socialist tradition of Tony Cliff.

But theory is grey and the tree of life is green. Theory is compelled to lag behind, seeking to define being when in fact there is only becoming, seeking to define what is when it has already become something else. Marxism – the theory and practice of international working-class revolution – comes closest to comprehending holistically the fluid, shape-shifting, eternally evolving nature of social reality in all its complexity, its contradictory interconnectedness, its dynamism. But Marxism cannot float through the ether; to exist it must be embodied in human practice, in the work of groups of thinkers and activists, in political organisation and the class struggle. And there it congeals into traditions and parties and sects and camps, where it forms a sediment of fossils. But in the social world, the living world, there is only motion, an eternity of change, an unstoppable torrent of becoming.

So Marxism is an unfinished research programme. Its subject matter is the past, the present, and the future, but its cutting-edge must always lie where the present is becoming the future, where contemporary theory and practice – what human-beings do – will decide the form of the future.

In this roundabout way I come to a special acknowledgement to my two closest theoretical collaborators, Phil Hearse and William I Robinson. The influence of their thinking on mine can be found on every page of this essay.

6.

Some of what follows is, therefore, an attempt at a new synthesis in which I use the 180-year-old Marxist research programme to understand the crisis of capitalism, society, and planet in the third decade of the 21st century. Relevant to this are several earlier books of my own, but in particular two studies written in collaboration with Phil Hearse and other comrades, Creeping Fascism: what it is and how to fight it and System Crash: an activist guide to making revolution. Yet more important, however, is the work of our American colleague William I Robinson, whose perspectives, developed over more than two decades, are presented in a series of seminal studies, including, most recently, The Global Police State. The analysis presented here builds on this foundation.

7.

I must alert readers to the dangers of a) over-abstraction and b) undialectical one-sidedness in some of the formulations in this essay. My aim is a compressed theoretical overview and a (relatively) fast read. This means stripping out caveat, nuance, qualification. This gives rise to the two dangers.

The truth is always concrete. True statements about social reality must concern the living, practical, material world as it really is. That world is a contradictory unity in motion. It is a collision of forces that are both bound together in a single social reality and yet at the same time are in conflict with each other. To focus on one aspect of reality is to abstract it from the ensemble of social relations that constitute the whole and, in a sense, to defuse it (in a theoretical sense) by disconnecting it from the other forces with which it is interacting.

One aspect of the eternal dialectical motion that constitutes social reality is that nothing that came before is ever entirely erased. Just as we bear a physical form evolved from earlier hominin species, so present-day society carries within it the reconfigured forms of past society. The third alienation, for example, is superimposed on the second, and the second on the first. History is a concretion of layers, ever deepening.

The text should therefore be read with two red warning-lights switched on: beware over-abstraction and undialectical one-sidedness.

8.

A more profound reason for over-abstraction and undialectical one-sidedness is that the totality of the contradictory unity in motion that constitutes social reality cannot be comprehended all at once. The complexity and fluidity of the whole ensemble of social relations preclude cognitive grip. It is as if we wanted to catch hold of a great river.

We are compelled, therefore, to proceed by the method of extrapolation and exposition of primary tendencies; theoretically, we must identify, examine, and define these, before placing them back in their context of the whole ensemble of social relations, the whole contradictory unity in motion. Abstraction and undialectical one-sidedness are unescapable parts of the analytical process.

9.

I have adopted two unusual conventions in the text. Because the essay is a concise theoretical summation rather than an extended discourse, I have divided each chapter into a succession of numbered points of diverse character and variable length. And because the summation hinges on a series of key theoretical concepts, both vintage and newly coined, I have retained italics throughout in referencing these.

Chapter 1

Stasis

1.

Stasis is an Ancient Greek word for which no direct English translation is possible. It means both civil strife (class struggle) and political deadlock (systemic crisis) at the same time. Stasis was the word used by the Ancient Greeks to describe a revolutionary situation.

Revolutionary situations can have three possible outcomes: victory for the revolutionary forces, the destruction of the ancien regime, and the establishment of a new political order; victory for the counter-revolutionary forces, the destruction of the popular movement, and the re-imposition of the existing order; and what Marx called ‘the common ruin of the contending classes’. More prosaically, in relation to the modern world, we may speak of a choice between ‘socialism and barbarism’.

Stasis defines the current global crisis. Accelerating ecological and social breakdown threatens the survival of human civilisation. The breakdown is propelled by the dynamo of global capital accumulation. Popular revolution to terminate the rule of capital is an existential imperative. Yet the revolutionary forces (the democracy) are not yet sufficiently organised, mobilised, equipped, and coordinated to defeat the counter-revolutionary forces (corporate capital and the global police state). Therefore, the road to an alternative future is currently blocked, and we continue the slide towards oblivion.

2.

In this chapter, I focus on symptoms, not causes or cures. I seek to identify the main expressions of the global stasis – our current chronic condition of accelerating ecological and social crisis combined with political paralysis.

I offer the briefest summary without empirical substantiation. Fuller treatment can be found in our System Crash, and of course in many other studies.

3.

Climate change due to global warming is fast accelerating. All key indicators – carbon emissions, atmospheric loading, global temperatures, sea-levels, etc – are on a rising curve. Numerous signals – glacial melt, heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, storms, floods, etc – indicate that critical planetary boundaries have been breached. Climate catastrophe is already happening, with critical tipping-points now passed and irreversible changes unrolling. We have entered uncharted territory in which multiple, complex, unpredictable feed-back loops begin to transform the ecology of our planet.

The climate crisis can be understood as a metabolic rupture between Nature and Society – Nature in the sense of a finite but renewable resource of organic and inorganic matter capable of sustaining human life; Society in the sense of a global system of production, destruction, and waste propelled by capital accumulation.

4.

The Covid-19 pandemic constitutes another form of metabolic rupture. Whereas the climate crisis arises from the destruction of an existing ecology, the pandemic arises from the creation of a new ecology.

The replacement of the existing ecology by a new ecology based on the expropriation of the commons, the dispossession of the poor, the levelling of the wilderness, and the creation of vast monocultures has created countless global breeding-grounds for disease. The loss of biodiversity and natural firebreaks has released deadly pathogens previously trapped inside the forest. Factory farms packed with genetically identikit domesticates, slum cities filled with dispossessed people, and globalised supply-chains have created ideal conditions for the mutation and transmission of new and lethal viruses.

Covid-19 is now endemic. It will continue to evolve, giving rise to new, more transmissible, more vaccine-resistant variants. It is bleeding into a growing pandemic of Long Covid. It is squeezing capacity for other kinds of healthcare in the Global North and overwhelming all health provision across much of the Global South. It impacts disproportionately the old, the frail, the sick, the disabled, the poor, and the oppressed.

Covid-19 is still raging across the world. But corporate agribusiness has laid the foundations for an endless succession of viruses and variants. The next pandemic is only a matter of time.

5.

Climate and Covid are currently the most visceral expressions of the metabolic rupture. But a series of other planetary boundaries are breaking down. The nitrogen cycle, the acidity of the oceans, the loading of the environment with plastic micro-waste, the dumping of toxic pollution into land and sea, air pollution, etc: these and more are ecological crises in their own right.

6.

The productive capacity of humanity – our ability to satisfy collective human need – has never been greater. This is mainly the result of the First, Second, and Third Industrial Revolutions combined with the vast expansion in world population (now 7.5 billion) consequent upon them. Technological advance has raised the productivity of labour to an unprecedented level. The labour-force available for productive work is greater than ever. Our exponentially enhanced capacity to produce use-values means that we are better able to provide food, clothing, shelter, comfort, education, healthcare, creative opportunity, personal fulfilment, and human self-realisation than ever before in the history of our species.

At the same time, the absolute mass of human suffering in the world has never been greater. Even the barbarism of poverty, fascism, war, and genocide between 1929 and 1945 – which culminated in the deaths of 60 million people – does not compare with what is now unfolding. The ecological and social crisis of the early 21st century threatens hundreds of millions with premature death and disablement and thousands of millions with lives of increasing toil, destitution, disease, and misery.

This contradiction – between productive capacity and human suffering – arises from the alienation of humanity from nature, from society, from the means of production and subsistence, from the products of labour, from its own creative powers. It arises from the usurpation of control by capital and the subordination of productive capacity to the imperatives of capital accumulation.

This alienation has given rise to unprecedented inequality in the distribution of wealth and income. The global class structure now comprises: 1) a tiny elite of super-rich billionaires (numbered in the low thousands); 2) a broader elite of multi-millionaires (numbered in the low millions); 3) a large middle class of career administrators, managers, officials, professionals, etc who serve this elite and enjoy high material rewards (accounting for perhaps 10% of the world’s population); 4) an upper mass of small-business proprietors, self-employed professionals, and skilled workers in relatively secure employment (around 30% of the total population); 5) a middle mass of workers in more casual, insecure, lower-paid ‘precarious’ employment (around 30%); and 6) a lower mass of destitute ‘surplus humanity’ more or less excluded from regular employment and attempting to survive on the margins of the economic system (around 30%). Overall, the richest 1% hold twice as much wealth as the entire world working class (groups 4, 5, and 6 combined).

The social crisis – the contradiction between human productive capacity and unsatisfied human need – is a direct consequence of global inequality in the distribution of wealth and income. This inequality is a direct consequence of an economic system based upon capital accumulation.

7.

Human needs are social needs. Britain’s National Health Service can serve as a concrete example. It employs a million people. It treats a million patients every day. It exists to provide first-class medical care, free of charge, to all who need it, at the time and in the place of need. It is a masterpiece of administrative co-ordination, integrated care, and dedicated professional work designed to maximise healthcare outcomes. It is a model of cooperative labour, public service, and human solidarity.

The NHS is slowly deteriorating because the British political class, on behalf of the corporations they serve, are implementing a deliberate programme of underfunding and outsourcing designed to privatise the service. Public service is to be replaced by private profit. The result will be cost-cutting, falling standards, reduced services, increased charges, and eventually two-tier healthcare access based on ability to pay.

The slow-motion demolition of the NHS is a vivid example of the global destruction of the commons by advancing capital accumulation. The corporations are creating a world of private greed and public squalor.

8.

The ecological and social crisis is causing political and geopolitical breakdown. People are being dispossessed and displaced, their livelihoods destroyed; a billion people have become internal or external migrants. As economic systems and social infrastructures dissolve, political structures implode into failed states, warlordism, mafia, the rule of the gun. Militarisation, violence, and war then set up new shock-waves of economic collapse and mass displacement.

Like a firestorm that grows by sucking in oxygen, the crisis becomes an accelerating vortex that feeds on the chaos of ecological, social, and political disintegration.

9.

Many wars are started deliberately. This was true of the Second World War, which was launched by the fascist regimes in Germany and Japan. Some wars arise from escalating tension, confrontation, and mission creep. The Vietnam War was of this kind: it began as a limited US intervention to prop up a client dictatorship, but evolved into a full-scale counter-insurgency war against a national independence movement. Yet other wars begin by accident; or rather, without the deliberate intent, and against the wishes, of the leading protagonists. The First World War was of this kind.

The European leaders would have avoided war in 1914 if possible. But they were unable to do so because Europe – a continent of warring states for hundreds of years – was too fractured by imperialist tensions, hostile alliances, vast armies, and complex war plans.

They would have been even more determined to avoid war had they known its consequences: 15 million dead, the fall of three monarchies, mass popular revulsion against existing elites and the established social order, and a tidal wave of global revolutionary struggle by workers and peasants that almost destroyed the capitalist system.

The world geopolitical system is a historically-formed patchwork of about 200 separate nation-states, ranging from global superpowers like the US and China to tiny countries of fewer than a million people. It is utterly dysfunctional. The ecological and social crisis is global and only global action can address it. Yet the framework of world capitalist politics institutionalises fragmentation, rivalry, nationalism, and militarism. This pathological geopolitical system contains an explosive charge capable of destroying everyone on the planet. A war between the major powers today – whether deliberate or accidental – could result in nuclear Armageddon.

10.

The primary expressions of humanity’s greatest crisis are: climate change, pandemic disease, soaring inequality and poverty, social breakdown, escalating violence, possible nuclear annihilation. These are the symptoms of a crisis that is driving us towards the abyss.

No aspect of the crisis is being adequately addressed. All aspects of the crisis are worsening.

The governing structures of the contemporary world order – the international institutions, summits, and conferences; the imperial states and their war-machines; the nation-states run by corrupt, pro-corporate, technocratic politicians – are unable to take effective action because they are embedded in a system based on private capital accumulation, not one based on human need and public service.

Revolution has become an existential imperative for humanity and the planet. But the popular masses are yet to achieve revolutionary agency. Therefore, at present, we continue the slide towards oblivion.

The term for this chronic condition of crisis and deadlock combined is stasis.

Chapter 2

Spectacle

1.

The paralysis of bourgeois politics means that the ecological and social crisis itself has been reduced to spectacle. In one or another of its multiple manifestations, it is the staple fare of global news (and fake news) feeds. Heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, famines, storms, mudslides, and floods are spectacles. Covid infections, collapsing health services, and mass graves are spectacles. Mass migrations, refugee camps, militarised borders, and capsizing boats are spectacles. Wars, massacres, gun-toting militias in Toyota pickups, exploding buildings and streets of concrete rubble are spectacles.

Because the crisis only continues and intensifies, because the proclamations of bourgeois politics have no practical meaning, and because the revolutionary alternative has not yet emerged, the crisis can only take the form of spectacle.

2.

To recapitulate, the concept of the spectacle derives from the Situationist perspective of Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle (1967). I have suggested his insight represents a third alienation, a third layer of human estrangement from the real world.

Alienation from productive work; alienation from real needs; alienation from the material world; this threefold alienation gives rise to a surreal, virtual, weightless social experience. Without anchors in practical activity and material substance, mass consciousness becomes free-floating. Because nothing is tested against reality and praxis, anything goes, anything is possible, anything can be true.

Covid is a hoax and vaccines are toxic. Heatwaves and floods are fake news. Islam is a conspiracy. Migrants are a threat. Jeremy Corbyn is a racist. Donald Trump is a genius. Boris Johnson loves the NHS.

Discourse is no longer communication about an actually existing world; it is an eternal shaking of a lucky-dip of soundbites, tweets, memes, and hashtags; an endless churning of data molecules without connection or context.

Increasingly, too, images replace discourse. Unmediated sensory experience then substitutes for any kind of thought, even the crudest, let alone scientific thought, rational thought, critical thought.

3.

Anything and everything can become spectacle. An infinite variety of images can be created with click-button speed. Images can be sent across the world in seconds. Billions of people act as transmitters. Billions of screens act as receivers.

The Roman ruling class used ‘bread and circuses’ to placate the Roman mob. The modern ruling class offers an endless succession of electronic spectacles – sporting championships, state ceremonies, celebrity weddings, commemorative events, international summits, music festivals, etc. They offer an ever-expanding range of instant-access, personally-selected, zero-effort electronic entertainment. They supply a constant drip-feed of electronic hoardings for every conceivable kind of consumer pap. They prey on neurotic unease, on low self-esteem, on the inner hollowness of alienated humanity. Frustrated aspirations – to be rich, beautiful, fashionable, elegant, sexy, clever, respected, successful, whatever – discover a catalogue of commodities to satisfy them.

Social media is also spectacular. Narcissistic self-exposures firecracker across the internet. Cereal-packet trivia clicks its way across cyberspace. FOMO-anxious addicts check their feeds, add their comments, make their shares – every hour, every ten minutes, every spare moment. Corporate algorithms read each click in a second and trigger a customised tweak to the flow of marketing, fake news, celebrity tittle-tattle, and other bullshit.

The internet becomes an immaterial world of virtual lives constructed of electronic bric-a-brac; a world of totally immersive alienation where nothing is done, nothing is made, where no real human relations are formed, no practical action performed, where species-being reduces to zero.

4.

Species-being is libidinal. Alienation is psychic rupture. Defined as a species by cooperative creative labour, our minds are hard-wired for connection with others, solidarity with others, union with others. The society of the spectacle, the third alienation, is therefore a form of mass psychosis. It means that libido – the psychic life-force – is no longer projected outwards to lovers, family, friends, colleagues, creative work, the public good, society as a whole – but is inverted into extreme narcissistic individualism.

The atomisation of society into individual workers, consumers, and spectators, the disintegration of civil society, especially of organisations of collective struggle like the unions, creates a psychic dystopia, a rupture of species-being at the most intimate level of basic libidinal health. It is characterised by what Fromm called ‘fear of freedom’ – a chronic, debilitating lack of confidence, independence, willpower, and creativity. It involves an inversion of deformed, misdirected libido, a lack of fulfilment and aspiration, a festering psychic misery liable to explosions of psychotic rage.

5.

The society of the spectacle is also a politics of the spectacle. Bourgeois politics comprises an endless sequence of displays – global summits, world conferences, meetings of state leaders, official visits, party conferences, parliamentary debates. International institutions – the United Nations, the World Economic Forum, the EU, NATO, many others – organise spectacles. National political institutions do the same. Each event is heralded with great fanfare, loaded with import, discussed gravely. Commentators describe the players, the body language, the nuances. They dissect the speeches and statements. Platitudes become wisdom. Vacuity becomes statesmanship. Nothingness becomes a historical event.

Take the annual COP conferences (United Nations Climate Change Conferences) held since 1995. The purpose of these international gatherings of thousands of politicians, scientists, and lobbyists is to agree, coordinate, and implement a global response to climate change. The fate of the planet is imagined to hinge on the outcome. But COP is only a spectacle. The accelerating gravity of the crisis, and the measures necessary to resolve it, are explained. Then targets are set and pledges made that bear no relation to the measures necessary. Then these targets and pledges are forgotten anyway. COP turns out to have been nothing more than political showbiz.

The world has been getting hotter, and faster, for 25 years. Since the first COP conference, increases in carbon emissions, atmospheric loading, global temperatures, and sea-levels have continued to accelerate. COP has made no difference.

Take another example: the bourgeois political response to the Covid-19 pandemic. This ranges from the fascist-eugenicist policies of far-right regimes like that of Johnson in Britain to the attempted containment policies of more liberal regimes like that of Biden in the US. But, in the context of a global health emergency, the mainstream political system is incapable of implementing a comprehensive programme of appropriate action. Nor does the official ‘opposition’ even raise the most basic and obvious reformist demands. In Britain, for instance, those demands might include: huge public investment in expanded healthcare capacity; a big pay rise for NHS staff and a massive recruitment and training programme to fill vacancies; immediate termination of all outsourcing and privatisation in the NHS; abolition of patents, nationalisation of Big Pharma, and huge public investment in vaccine production and roll-out for the Global South. The Labour Party could champion these demands. The trade unions could fight for them. But they are not even mooted. The dominance of neoliberal ideology, rooted in the imperatives of global capital accumulation, precludes a rational collective response to the pandemic. The age of reason and progress is over. We live in an age of madness.

Even the opposition has become part of the spectacle. Social-democratic and liberal parties, once standard-bearers of progressive reform, are run by career technocrats representing the rich and the corporations; their ‘opposition’ is façade. Trade unions, once the combat organisations of working-class struggle, have become bureaucracies of lobbyists. Campaign groups organise token marches, protests, and stunts, but they rarely transition from protest to resistance – from mere expression of dissent to class struggle capable of challenging the power of capital and the state.

Limited protest can be tolerated because it is part of the spectacle: momentary, regulated, ineffective, it is part of the façade of liberal-parliamentary democracy which masks the substantive reality of corporate power, capital accumulation, and the global police state.

Protest is not struggle. Struggle is an open clash of class forces, a direct pitting of the collective power of workers, the oppressed, and the poor against the repressive power of capital and the state. Strikes, pickets, occupations, blockades, etc – anything that challenges the power of capital and the state – is constrained by bourgeois law and police repression. So real struggle invariably involves mass law-breaking and confrontations with the police. Class struggle looks like the miners strike of 1984-5 or the poll tax revolt of 1989-91. It strips away the liberal veneer of the state to expose its repressive essence. When capital is threatened by struggle from below, the state is revealed as ‘armed bodies of men and women’ (Engels).

6.

Bourgeois politics is now part of the society of the spectacle. Unable to address effectively any aspect of the accelerating ecological and social crisis – because that crisis is rooted in the imperatives of world capital accumulation and therefore cannot be resolved without international revolution and a red-green transition powered by popular mass mobilisation from below – all kinds of bourgeois politics, including formalised dissent and ‘opposition’, become form without content, façade without substance, a succession of spectacles.

Mainstream politics, official politics, despite all the pomp and circumstance, is just another part of the Wall. It is wholly encompassed within the third alienation. It reflects humanity’s loss of control over the material world that is both its natural substrate and its active creation.

Chapter 3

Creeping Fascism and Global Police State

1.

Fascism is the hyper-charging of a nexus of traditional reactionary ideas – authoritarianism, militarism, nationalism, racism, sexism, homophobia, etc – to create an active counter-revolutionary political bloc. It provides capital and the state with a mass electoral base and a mass street force, including, when necessary, armed militia, in the context of deep and intractable social crisis.

2.

Fascism is a process. It develops in relation to the crisis and in collision with other social forces. Before the outbreak of the Second World War, six years after Hitler came to power, there were only about 25,000 people in Nazi concentration camps, and only a few hundred people had been killed by Nazi paramilitaries. The conquest of Poland (1939) and then western Russia (1941) created the context for the Holocaust. Only in 1941 did the Nazis commence large-scale mass murder, and only in 1944 did this reach a peak with industrialised genocide in purpose-built extermination camps. They eventually murdered about 20 million. Fascism must be understood as a tendency, not a fait accompli.

3.

The existing bourgeois state apparatus is always the primary instrument of fascist repression and totalitarianism. The state is reconfigured by a process of gleichschaltung (‘coordination’) – achieved by a mix of purge, intimidation, and indoctrination – and thus brought into line with fascist ideology and programme. Fascist paramilitaries are always auxiliaries.

4.

Fascism takes many different concrete forms. The Italian Fascists took several years to complete the process of gleichschaltung and create a totalitarian state; they never organised a systematic genocide. The Spanish Falangists remained a subordinate part of a counter-revolutionary alliance led by army generals during the Spanish Civil War; they supplied military contingents and death-squads. The Japanese Militarists had their origins as a movement of army officers; they transformed the existing army into the primary mechanism for creating a totalitarian state.

5.

Second-wave fascism – what we have called creeping fascism – is different from first-wave interwar fascism. Two differences are especially significant.

First, the absence of a mass, organised, militant working-class movement means that fascist paramilitaries and street-fighting are less necessary; the primary role of the existing bourgeois state in the development of fascism is even more pronounced.

Second, the exceptional atomisation and alienation characteristic of neoliberal capitalism mean that the blood-and-soil nationalism, imagined communities, invented traditions, etc of interwar fascism – where the individual is subordinate to and subsumed within the mass – is no longer dominant. Instead, creeping fascism is underpinned by extreme narcissistic individualism. The culture war is essentially an ideological struggle between the solidarity and humanity represented by the progressive working class and the nihilistic selfishness of a proto-fascist reactionary bloc formed of the petty-bourgeoisie and a ‘lumpenised’ reactionary working class.

6.

In interwar fascism, the leader represented the authoritarian father-figure of the traditional patriarchal bourgeois family. The ‘little man’ (Reich’s term), in flight from freedom, seems to have found relief from guilt, anxiety, and insecurity through immersion in the mass, in a swallowing up of person in the movement and the nation, in obedience to the all-knowing, all-powerful, God-like leader.

The mass psychology of second-wave fascism is differently configured. Instead of libido dissolving into a mythic national community, it is inverted, turns in on itself, becoming an extreme, selfish, narcissistic individualism. The leader is no longer an authoritarian father-figure, but a mirror in which the hyper-alienated, socio-pathic, self-obsessed consumer-spectators of an atomised social order see themselves.

7.

Creeping fascism creates an ideological and political mass base for capital and the state in a period of acute and accelerating crisis in which reform and improvement are precluded. But the system cannot hope to achieve general consent. The material reality of deteriorating social conditions, of increasing exploitation, oppression, and poverty, means explosions of popular rage against the system. This in turn means more militarised and violent police repression. William I Robinson uses the concept of the global police state to analyse this development.

8.

Global police state does not mean that there is a single, centralised, pan-global police authority. It means that each nation-state deploys police to safeguard the interests of transnational capital within its own national territory – much as individual police departments operate in separate localities inside each nation-state.

9.

In addition to crushing mass resistance to the rule of capital and the state when necessary, the global police state has also become a primary form of modern capital accumulation.

During the Cold War, the permanent arms economy involved high levels of state arms expenditure, lucrative contracts for arms manufacturers, and a multiplier-effect stimulus to the wider economy; the military-industrial complex was one of the engines of post-war capitalism.

Today, in addition to continuation of the permanent arms economy in the context of the War on Terror, there is unprecedented expenditure on militarised policing, border controls, detention-centres, mass surveillance, etc. Militarised accumulation – state spending on armed forces, police, and repression – is an engine of neoliberal capitalism.

10.

The Wall – the society and the politics of the spectacle as transmitted through cyberspace to ten billion screens – is capital’s first line of defence. The Wall combines mind-numbing pap, consumerism, and reactionary ideology. It is the primary mechanism for achieving consent, indifference, apathy, passivity, etc in the context of escalating ecological and social crisis.

But as the crisis deepens, the system is threatened by spontaneous explosions of popular revolt from below. Creeping fascism divides the working class and provides capital and the state with a mass political base and auxiliary street forces in the face of popular revolt. The global police state provides the concentrated, militarised, repressive power to smash such revolt.

The existing bourgeois state apparatus is both the primary agent of creeping fascism and the local franchise of the global police state. Mass surveillance, repressive laws, militarised police, and nationalist-racist ideology herald a new totalitarianism.

Chapter 4

Corporate Power and Capital Accumulation

1.

Capital can be defined as the self-expansion of value – in Marx’s formula, M – C – M+, where M is the money capital originally invested, C is the conversion of this money capital into plant, labour, and raw materials during the production process, and M+ is the return to the money form when commodities are sold, but with added value (profit).

Without profit, there is no incentive to invest and there is economic stagnation and mass unemployment. The world capitalist economy expands at the rate of approximately 3% per annum; this means it doubles in size every quarter of a century. Capitalism is a system of exponential growth without end.

2.

Capitalism is a highly contradictory economic system. It is characterised by a long-term tendency towards over-accumulation and under-consumption.

Workers are paid less than the value of their labour; if this were not the case, there would be no profit. This means the working class as a whole cannot consume the entire output of its labour, because the aggregate value of wages is always lower than the aggregate value of the commodities produced. The system therefore has a built-in tendency to become overloaded with surplus capital.

3.

The long-term tendency towards over-accumulation and under-consumption has become more severe with the development of monopoly-capitalism, where each sector of the economy is dominated by a small number of giant firms able to collude to reduce competition, manage markets, create demand, fix prices, and increase profits. The effect is to further overload the system with surplus capital.

It was monopoly-capitalism that created the consumer society based on false needs critiqued by Herbert Marcuse in One-Dimensional Man (amongst others). Seminal theorists of monopoly-capitalism – and of the growing tendency towards stagnation due to over-accumulation and under-consumption – were Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy, notably in The Theory of Capitalist Development (1942) and Monopoly Capital: an essay on the American economic and social order (1966). The work of Baran and Sweezy has provided the foundation for further work by John Bellamy Foster and other theorists associated with Monthly Review.

4.

From the late 19th to the late 20th century, world capitalism was dominated by giant multinational/imperialist corporations. The handful of corporations dominant in each sector tended to retain a primary national base where most production was concentrated, but they sought raw materials and markets on a global scale. This explains the murderous imperialist wars – essentially attempts by rival great powers to redivide the world in the interests of their own capitalists – of the early 20th century (the First and Second World Wars), and also the nuclear-armed confrontation and local proxy wars of the late 20th century (the Cold War).

But – as William I Robinson has explained in A Theory of Global Capitalism (2004), Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Humanity (2014), and other works – the neoliberal era (c.1975-present) has seen a shift from multinational to transnational capital. Whereas multinational capital remains anchored in a primary national base, transnational capital, irrespective of where a corporation is headquartered/registered, is characterised by fully globalised production, distribution, and marketing. Transnational capital is now the hegemonic fraction of global capital, dwarfing the operations of national, regional, and local capitals.

The transnational giants are often hollow corporations. This is especially true of finance and tech giants. These are dominant by virtue of control over money capital and/or marketing networks. They produce nothing – all production is outsourced – but they cream off the bulk of the profit.

The dominance of transnational capital and the emergence of hollow corporations are in large part a consequence of the Third Industrial Revolution based on digitalised-electronic data capture, storage, and processing, and on instant online global communications.

5.

Throughout its existence, capitalism has been compelled to find ways to resolve its intrinsic crisis of over-accumulation by offloading surplus capital. Because the crisis of over-accumulation has intensified over time, this process has become increasingly pathological. It has reached a new peak in the neoliberal era. It is the underlying and deepening crisis of over-accumulation that explains all the following characteristics of contemporary capitalism: financialisation, rising exploitation at the point of consumption, hyper-consumerism, the privatisation of the commons, and state-funded accumulation.

6.

Financialisation is accumulation through the creation and investment of fictitious money capital. Governments and banks create money by entering numbers in computers. This money can then be invested in financial assets. These assets return a profit either in the form of interest or because they have attained higher value when sold on.

Money is a form of debt. Financialisation is anchored in rising levels of debt – public, corporate, and household – typically with real estate as the foundation, especially mortgages. But this anchorage is insecure.

Mountains of fictitious capital are created. Financial asset values tend to rise because of the continuing flow of new electronic money into the system, and trading can sometimes become frenzied, with exponentially rising values, speculative bubbles, and banking crashes.

Nothing is produced. Financialisation means profiting without producing. It is pure parasitism. If the formula for industrial accumulation is M – C – M+, that for financial accumulation is M – (M) – M+, where M is the money capital originally invested, (M) is the financial asset purchased, and M+ is the increased money capital realised through interest payments or rising asset values.

Debt-based financialisation – the ‘permanent debt economy’ – has absorbed a huge and rising mass of surplus capital in the neoliberal era.

7.

The working class is exploited as workers at the point of production (where it is paid less than the value of its labour) and as consumers at the point of consumption (in the form of fees, rents, high prices, interest on debt, state taxes, etc). The neoliberal era has seen a relative shift to higher rates of exploitation, and therefore surplus accumulation, at the point of consumption.

This shift has been underpinned by rising levels of debt. Working-class households are now saddled with unprecedented amounts of debt. Both the debt itself and the higher levels of consumption it enables are sources of profit.

8.

The consumer society powered by false needs has been hyper-charged under neoliberalism. Debt enables high levels of consumer spending despite falling or stagnant wages. The sales effort (branding, packaging, advertising, etc) now takes the primary form of customised online spectacle mediated by corporate algorithms. Atomisation and alienation stimulate neurotic consumerism. The spiritual emptiness of everyday life, the psychic misery of modern humanity, creates a mass market for every species of corporate snake-oil merchant.

9.

The remaining commons – social housing, public healthcare, major utilities, public transport, local services, etc – are being sold off to private capital.

Services once provided collectively by government agencies and at public expense are now contracted out to private corporations. In effect, state taxes, instead of funding not-for-profit public services, to fund private capital accumulation – a direct transfer from working-class incomes (levied as taxes) to corporate profit.

10.

In the mid 20th century, the state played a proactive role in economic management, with high levels of public provision, nationalisation, regulation, etc. In the early 21st century, the role of the state is to service transnational capital.

As well as crushing resistance from below as the local franchise of the global police state, the modern nation-state apparatus provides contracts, subsidies, and bailouts to private capital, recycling tax revenues and state debt into corporate profit.

That takes many forms. Militarised accumulation – rising expenditure on armaments, police, prisons, security, borders, spying, etc – is one. State bailouts of bankrupt banks after speculative bubbles burst is another. Contracting private health corporations to provide NHS services is a further example. There are many more.

11.

Modern capitalism can be defined as a system of globalised, financialised, monopoly-capitalism, dominated by transnational mega-corporations, afflicted with a chronic and deepening crisis of over-accumulation and under-consumption, increasingly prone to stagnation and slump, and increasingly pathological and parasitic in its efforts to unload surplus capital.

Nonetheless, the neoliberal mix of financialisation, permanent debt, manic consumption, privatisation, and state-funded accumulation sustains ongoing global capital accumulation even in the face of accelerating ecological and social breakdown.

The future – under the rule of capital and the global police state – can be expressed in a simple formula, (M – C – M+)∞ = X, where (M – C – M+) is capital accumulation, ∞ is infinity, and X is extinction. Because capital is, by definition, the self-expansion of value, exponential growth without limit until the end of time, it now constitutes an existential threat to human civilisation.

The second part of this essay considers the alternative: international revolution from below to create real democracy, restore the commons, and effect a red-green transition to an egalitarian social order and an ecological sustainable economy.

Chapter 5

The Commons

1.

The history of the class struggle for 5,000 years has been the history of the struggle between private property and the commons.

In pre-class society, nature, the land, the means of production, etc had been utilised collectively. Only with the development of class society – in which a few who did not work lived off the labour of the many who did – was it necessary to create forms of private property.

The forms have varied. Property might be held by an elite collectively. Ancient temple priesthoods, the medieval church hierarchy, the multiple shareholders of a big corporation, and modern party-state bureaucracies are all examples. Or it might be held by a single owner or family. But the principle is the same: private property is the usurpation of the commons by a ruling class.

2.

Only now is the long class war between private property and the commons reaching completion.

In the medieval period, some peasants still owned their own land, many had customary tenancies hedged with legal protections, and all enjoyed a range of common rights, like free access to the woods to collect firewood or pasture pigs. Most peasants had their own plots, their own tools, and provided much of their own subsistence, even if they had obligations to their lords to perform labour-service and pay rents, tithes, and taxes. Manorial court records are full of disputes which revolve around the respective (private) rights of the lords and (common) rights of the peasants.

Capitalism involves the displacement of the peasantry from the land, its dispossession of its own means of production and subsistence, and its conversion into a working class without property or common rights, and therefore with nothing to sell but its labour-power.

It is this process – part of the wider 500-year process of capitalist globalisation – that is now reaching its completion with the slow destruction of the residual peasantry in the Global South.

3.

Though the long-term trajectory is towards destruction of the commons by the ruling class, the curve is uneven. Upsurges in class struggle from below can interrupt, even reverse, the process.

During the ‘trade-union century’ (late 19th to late 20th century), the working class was strong enough to win major social reforms and thereby expand the terrain of the commons. The welfare states of this period involved subsidised social housing, controlled rents, free education, free healthcare, and much more – an expanded realm of collective provision at public expense.

But the world crisis of the 1970s and the neoliberal counter-revolution of the 1980s brought this period to an end.

4.

The power of the trade unions (and of the reformist social-democratic political tradition based upon them) was broken during the 1980s. Over the last 40 years, workplace trade unionism, rooted social-democratic politics, and working-class community more generally have largely disintegrated; the working class has ceased to be an organised collective force; society has been atomised, reduced to its smallest units, the individual worker, consumer, spectator.

Token protest has replaced class struggle. It may be planned – like the Occupy and Extinction Rebellion movements – or it may be more spontaneous – like the Black Lives Matter and Palestine Solidarity demonstrations. But the protests rise like a rocket only to fall like a stick. The dog barks but the caravan moves on. There is much noise, but capital and the state are not threatened, policy does not change, and the protests turn out to have been merely another kind spectacle.

5.

The destruction of the commons therefore continues apace. The dissonance between thought and action, rhetoric and policy, spectacle and substance has never been greater. The Tories clap for the NHS while pushing forward its privatisation. They proclaim outrage at racist abuse of football players while militarising the border against African migrants. They condemn men’s violence against women but order a police attack on a vigil for a murdered woman. They host a climate-change conference but continue expanding fossil-fuel capacity, subsidising carbon polluters, building new roads, and ripping up environmental protections.

The dissonance extends to dissidents and protestors. Most are merely lobbyists who ‘call on’ the political representatives of capital and the state to halt privatisation, eradicate poverty, take action against racism, end male violence, stop global warming, etc. They ‘call on’ the ruling class to halt the destruction of the commons by global capital accumulation – much as one might have ‘called on’ slave-owners to abolish slavery or feudal lords to abolish feudalism.

6.

Capitalism is the most rapacious, relentless, all-consuming social system in human history. Previous social systems were geographically localised and slow to develop. Capitalism is a dynamic system of global reach and exponential growth, eternally restless, eternally pushing towards, and finally beyond, what is ecologically and socially sustainable.

After 5,000 years of class society, and especially after 500 years of capitalist class society, the usurpation of the commons by private property now threatens the very survival of human civilisation. The restoration of the commons has become an existential imperative. This can be achieved only by the overthrow of the global police state, the dispossession of the rich, the halting of capital accumulation, and the creation of a new democratic order. It can be achieved only by ending of human alienation. It can be achieved only by an international revolution of the working class, the oppressed, and the poor.

7.

The alternative – the unalienated world of the commons – exists in microcosm everywhere. On an NHS hospital ward, integrated teams of doctors, nurses, allied professionals, and ancillary staff engage in skilled, cooperative, practical work devoted to human welfare. That work is poisoned by the miasma of capital – it occurs in a context of underfunding, privatisation, staff shortages, stagnant/falling wages, excessive hours, and management bullying. The contradiction between the unalienated world of the commons and the alienated world of capital accumulation is a lived daily experience in public service. But here we glimpse a possible alternative future.

Chapter 6

The Democracy

1.

Democracy, like stasis, is an Ancient Greek word. The demos – in contrast to the aristoi (nobles) or oligoi (the few) – was the majority fraction of the citizen-body of the polis (city-state), mainly farmers but also craftworkers, petty traders, and other working people. The demos did not include women, children, slaves, and foreigners. Only freeborn adult male citizens had political rights. But this gives the word a special meaning: the demos was the citizen-body organised as a political force.

The history of the Greek city-states is the history of the class struggle between the many (demos) and the few (oligoi). Greek democracy was the active, direct, participatory democracy of the sovereign demos. Modern liberal-parliamentary democracy, by contrast, is a façade of spectacles masking the power of capital and the state, where the masses are passive election fodder.

The term democracy is here used in the Ancient Greek sense. It implies an organised, mobilised, self-acting social force.

2.

Reappropriation of the term democracy is necessary.

The entire reformist tradition hinges on the idea of representation: workers are not expected to exercise power directly, but to elect politicians to represent their interests and carry out reforms, in the framework of liberal-parliamentary democracy, that is, in the framework of the bourgeois state. Social-democratic politics is thereby incorporated into the system and becomes a mechanism for channelling and containing the class struggle. It is a pressure-value to protect the system.

The entire Stalinist tradition also hinges on the idea of representation. In this case, however, a party-state bureaucracy (and its repressive apparatus) is imagined to represent the interests of the working class. The absurd notion that a totalitarian dictatorship, complete with censorship, secret police, violent suppression of dissent, a network of prison camps, a massive war machine, etc, can somehow represent the interests of the working class has been shockingly tenacious for almost a century, ever since the destruction of the last vestiges of the Russian revolutionary movement by Stalinist counter-revolution in the winter of 1927/8. This notion evolved into ‘campism’ when the Stalinist monolith broke up, with different Stalinist states – Russia, Yugoslavia, China, Albania, etc – at loggerheads. We ended up with pro-Russian, pro-Chinese, pro-Cuban, even pro-Albanian etc political sects.

One consequence has been intractable semantic confusion. Terms like socialism and communism have lost clarity because of their appropriation by Stalinism. That is not to say that democracy is not also a tainted term. But it has this virtue. It reasserts the living essence of the revolutionary Marxist tradition. It underlines that the emancipation of the working class is the act of the working class – not the act of reformist politicians, or party bureaucrats, or tanks with red stars – and that the necessary organisational form of such self-emancipation is mass, participatory, democratic assemblies.

3.

Every revolutionary movement involves an organised democracy of popular forces. In the French Revolution of 1789-94, it was the Paris sections in each suburb – local democratic assemblies of the urban sansculottes (working people) – that became the main engine of the revolutionary process. Each section sent its representatives to the city-wide Commune. A similar political structure was replicated by the Paris Commune of 1871.

In the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and 1917, the soviets – democratic assemblies of workers, soldiers, sailors, and peasants – played an equivalent role. The local soviets sent their delegates to the Petrograd Soviet, and this became the main organising centre of the entire revolution. It was the concentrated expression of the democratic will of hundreds of thousands of people in the capital city.

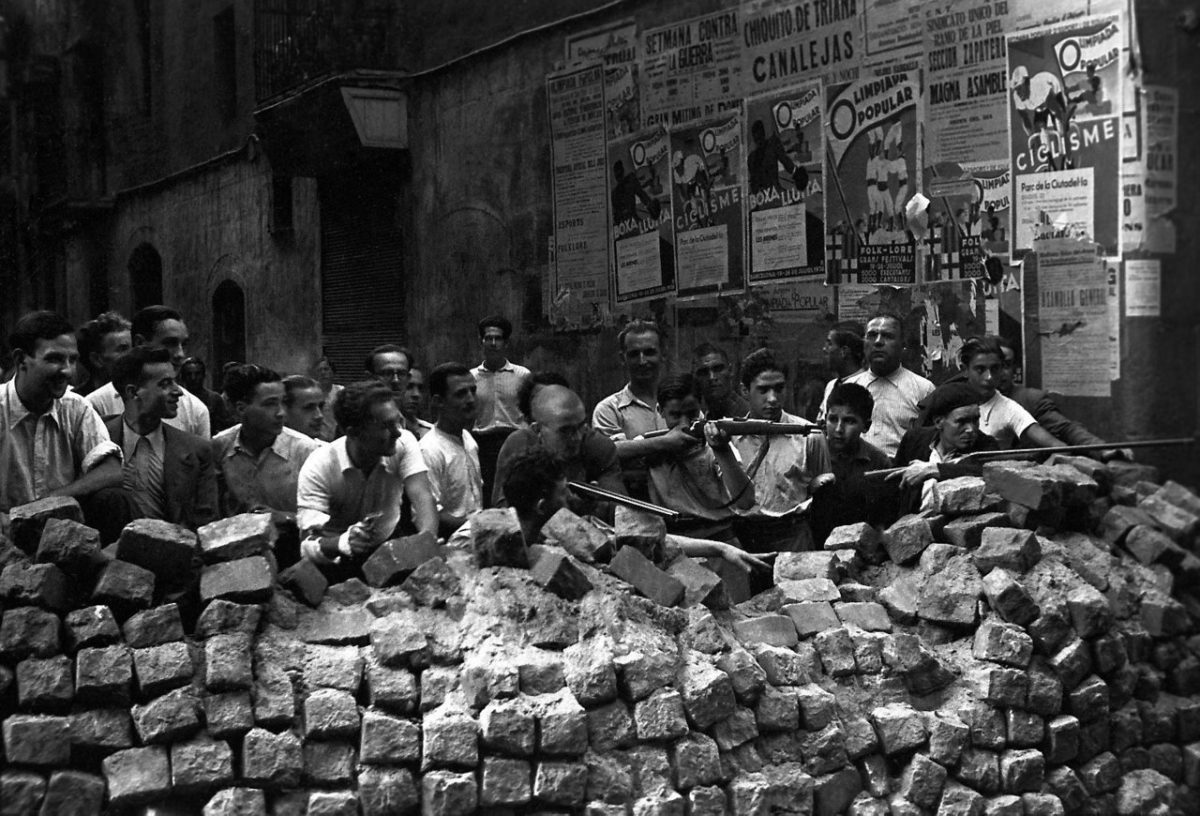

Other examples of mass participatory democracy in the context of revolutionary struggle could be cited – the committees and militias in Catalonia during the Spanish Revolution of 1936-7, the Budapest workers council during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, the cordones in Chile in 1970-3, the shuras in Iran in 1979, and many more.

But less advanced forms of class struggle also involve democratic organisation. Mass struggles by British workers against the Tory Government of Edward Heath between 1970 and 1974 defeated a programme of wage cuts and union-busting. These struggles involved strikes, mass pickets, open defiance of the law, and violent clashes with the police. Central to the movement was a nationwide network of shop-stewards (elected workplace representatives) and workplace mass meetings where decisions were made by show of hands.

The 1984-5 British miners strike was organised by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). Each colliery had its own NUM lodge (branch). The lodge leadership was directly elected and regular mass meetings of the entire lodge membership were held throughout the year-long strike.

The 1989-91 poll tax revolt was organised by local anti-poll tax unions (ATPUs). Set up by activists on local estates, the ATPUs were open to all local residents who joined the tax strike.

Countless other examples of democratic organisation in the context of mass struggle could be cited. The central lesson of the historical experience is that revolutionary and other mass class struggles necessarily give rise to organs of democracy from below.

4.

Democratic assemblies are essential to effective struggle for the following reasons: they allow the largest possible number of people to share ownership and control over the struggle; they raise consciousness and commitment through the fuller understanding achieved by collective discussion; they increase confidence by bringing people together instead of leaving them isolated; they legitimise decision-making and encourage active participation; they create bonds of solidarity and mutual support. Democratic assemblies turn the masses in struggle into an active, participatory, practical democracy.

5.

Democracy in the sense used here is the embryo of a new social order, one where power flows upwards not downwards, where ordinary people are active decision-makers not passive election fodder, where the needs of the many become determinate.

The triumph of democracy requires the smashing of the state, the overthrow of capital, the restoration of the commons, and the transcendence of alienation.

6.

Between the late 19th and late 20th century, democracy took the primary form of trade union organisation at the point of production. In British history, this ‘trade union century’ was bracketed by two signal events, the victory of the London dockers in 1889, which launched a wave of unionisation among the semi-skilled and unskilled, and the defeat of the miners in 1984-5, after which union membership halved, workplace organisation disintegrated, and the union bureaucracies morphed into lobbyists and providers of personal services.