The final weeks of the Westminster parliamentary session of 2023 were dominated by a debate about the exact content of the Tories newest attack on migrants.

The Rwanda Bill is the latest in a series of bills on migration introduced by the Tories since they came to government in 2010; the Immigration Act 2014, the Immigration Act 2016 and the Illegal Migration Bill 2023; alongside a longer list of changes in regulations that affect migrants’ status, rights or obligation – or indeed clauses in other bills with similar impact, most focus on ways of further controlling what is referred to as ‘illegal migration’

This piece uses certain terms interchangeably – migrant, refugee, asylum seeker – because the ‘official’ discourse, let alone the legal framework, makes distinctions that don’t exist in long standing patterns of human behaviour, which pose no threat and are even socially beneficial. But these distinctions do fulfil a function for nation states and their governments – they make it easier to exclude some people and discriminate against others they can stereotype as being comparable to the excluded.

Refugees unable to provide sufficient documentation are regarded as ‘bogus’, despite the horrendous circumstances from which they may have fled. Circumstances that make obtaining legal documentation unlikely for the overwhelming majority. ‘Genuine’ asylum seekers are sometimes seen as worthy of support, while ‘economic migrants’ are condemned as people taking advantage. Most immigrant groups have comprised all of these. It is hard to separate them.

Their principles and ours

Much of media coverage treats governments’ fundamental arguments over migration as unquestionably correct, while some amplifies their reactionary arguments. But these positions are wrong.

People have always migrated, including across borders. Yes, we tend to use the term only for crossing borders when we are talking about people, but this is not part of the dictionary definition and it should be questioned. For example, someone who grows up in a remote agricultural community and then migrates to a megacity within the same state can experience as great a difference as someone crossing a border from one country to a similar country.

While better living standards, political freedoms or people from your own community play some role in motivating migration, particularly in terms of where someone migrates, most people leave their countries of origin because they are forced by factors such as war, repression, poverty and climate change, all of which are becoming more intensive.

Indeed, more people migrate within countries: an estimated 740 million internal migrants in 2009, with African and Asian countries struggling with debt and poverty absorbing three out of every four refugees in the world.

Today, the United States has more international migrants than any other country while India remains the top origin country for the world’s migrants. India has been a large source of international migrants for more than a century. In 2020, 17.9 million international migrants traced their origins to India, followed by Mexico with about 11.2 million and Russia with around 10.8 million.

Most migration is from low- or middle-income countries to high income countries though there are important exceptions; for example, the majority of Palestinian refugees driven out by the Israeli state live in camps in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. One recent and significant exception is the impact of the mass genocide of the Rohingya from Myanmar, 960,000 of whom fled to Bangladesh.

Governments of most political stripes use migration to divide electorates, to divert them from the system’s failures. Free movement is apparently acceptable for the rich and powerful, but not when someone seeks a job or home. It seems easier to resent, even attack, someone with less resources and less status than you than to think about how to change the inequity and injustice of the system that denies the needs and rights of the overwhelming majority. Simon Hannah looks at how these arguments, together with other aspects of right-wing populism such as transphobia and misogyny, operate in his recent article Capital is scarcity.

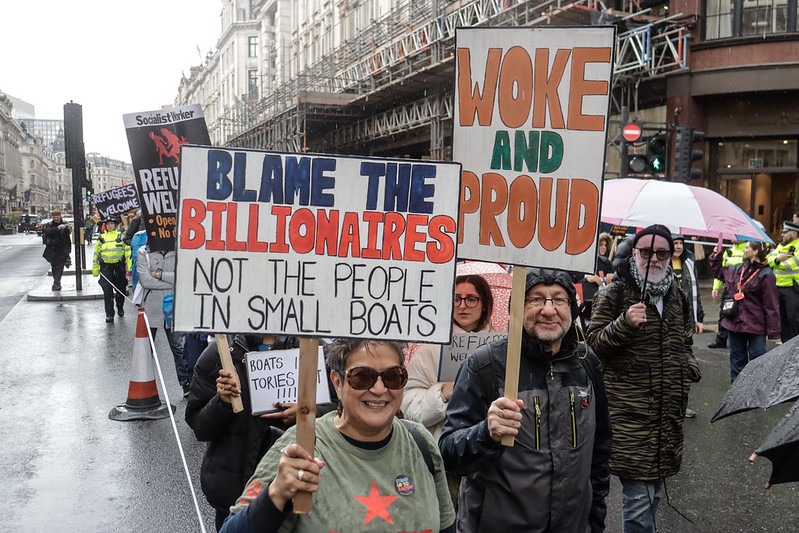

These are reasons why, in 2024, socialists must campaign to raise the loudest possible cries against not only the latest Tory attacks on migrants but the whole edifice of repressive laws and ideas on which they rest. No borders, no nations, no deportations.

Capitalist governments make policies and practices around migration that ignore or distort peoples’ real reasons for migrating. On occasion, they introduce special schemes for those fleeing particular wars – as Germany’s Angela Merkel did for those fleeing Syria and many European governments did for Ukrainians after the Russian invasion, but these are never extended into general principles.

Reserve army

Poverty is treated differently according to the shifting economic needs of states and governments. In the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Kuwait, three-in-four (or more) people are international migrants, and 90 per cent of all foreign workers in the UAE are from India, Bangladesh or Pakistan. Today, more than 3.4 million Indians and more than 1.5 million Pakistanis work in the UAE, making up about 39 per cent of the country’s population, mostly in unskilled jobs. As a reserve army of labour who can be paid less than local workers and are willing to work in appalling conditions with little or no protections this is an appealing situation. And the fact they can be attracted in or thrown out as local bosses need sweetens the prize even further.

In Britain there was a labour shortage after the Second World War, especially in transport and the newly created NHS. Migration was encouraged from mostly Caribbean countries – which were still British colonies until at least in the 1960s – though also from the former British colonies of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh even though thats not so often mentioned as part of the Windrush generation.

Under the British Nationality Act of 1948, everyone born within Britain’s colonies was considered a UK citizen. People in those places were brought up to look on Britain as the ‘mother country’. When London Transport, the NHS and the British Hotel and Restaurant Associations actively invited people from the colonies to settle for work in Britain, many jumped at the opportunity to better themselves and provide new opportunities for their children.

In 2012 under the coalition government, then Home Secretary Theresa May introduced a series of laws and regulations collectively called the Hostile Environment to make life harder for people without ‘leave to remain’ i.e. explicit permission to be in Britain to stay here – in the hope that many would voluntarily leave, saving the state the expense of deporting them. This was not targeted explicitly at the Windrush generation or indeed others from former British colonies.

But from 2013 increasing numbers started to receive letters claiming that they had no right to be in the UK. They were being treated as ‘illegal immigrants’, losing their jobs, homes, benefits and access to the NHS. Some were placed in immigration detention, deported, or refused the right to return from abroad. People had come to Britain before records were digitalised and few kept records for more than half a century. It subsequently became clear that the Home Office themselves had destroyed the landing cards proving when people had arrived. It took a lot of pressure to force a parliamentary apology in 2018, but that didn’t compensate the people whose lives had been destroyed. Financial compensation was promised – but as of June 2023 only a quarter of applications received anything.

This treatment of people from the Windrush generation shows the ideological and practical complexity involved. The British Empire – like all imperialisms – treated people it colonised as inferior beings in need of so-called civilisation. So the idea that the Windrush generation could have their papers destroyed, outrageous as it rightly seems, makes sense from the logic of that privilege.

On December 4 2023 a series of changes to regulations governing legal migration were announced by the new Home Secretary James Cleverly in the wake of the news that migration – of which illegal migration makes up only a small percentage – had risen significantly. Yvette Cooper, speaking for Labour in the House of Commons argued: ‘Net migration figures are now three times their level at the 2019 general election, when the Conservatives promised to reduce them. That includes a 65% increase in work migration this year.’

New rules include:

- Social care workers will no longer be able to bring dependants.

- The shortage occupation route will be tightened ‘to significantly reduce the number of jobs where it will be possible to sponsor overseas workers below the baseline minimum salary’.

- The baseline minimum salary to be sponsored for a Skilled Worker visa will increase from £26,200 to £38,700. These limits do not include those on a Health and Care visa, which encompasses social care.

- The Graduate visa, a two-year unsponsored work permit for overseas graduates of British universities, will be reviewed.

The additional point that received the most attention was the minimum income normally required to sponsor someone for a spouse/partner visa will rise from £18,600 to £38,700. As a result of protests from employers the Tories backed down from their initial idea of immediately increasing the limit by more than 100 percent. In less than three weeks, on December 22, the regulations were reformulated to state that the minimum income will rise in stages to £29,000 and ultimately around £38,700.

Racialisation, racism and immigration controls

The Windrush generation weren’t the first to be racialised by the British state.

By racialised we mean the process through which groups come to be designated as part of a particular “race” and on that basis subjected to differential and/or unequal treatment. Black people are more often racialised – while white people tend to be seen as ‘just people’.

When governments and the media talk about migration – and particularly migration as a problem – they are not generally referring to wealthy white people from the United States, Australia or South Africa.

Black migration to Britain goes back a long way – certainly to Roman Britain. Some of those we know something about as individuals were slaves or servants – but not all. Of the latter it’s unclear if they were treated less favourably because they were Black.

Racialisation has a number of mechanisms but immigration controls are important. The 1905 Aliens Act introduced immigration controls and registration for the first time into Britain, and gave the Home Secretary overall responsibility for matters concerning immigration and nationality. While the Act was ostensibly to prevent paupers or criminals entering the country and set up a mechanism to deport those who slipped through, one of its main objectives was to control Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe as people fled pogroms. Over 2.5 million of the 6 million Jewish people living in Eastern Europe fled between 1870 and 1914. Most went to Western Europe and America but between 120,000 and 150,000 arrived in Britain, most of whom flocked to London’s East End. They did not take ‘English workers’ jobs but were mostly employed by Jewish sweatshop owners.

Jewish immigration to Britain is documented as far back as the Norman Conquest, but it is difficult to trace individuals as religion was not a census question until 2011 and more significantly many people were pushed to convert to Christianity as a result of institutional antisemitism. Some who were more settled, especially those who had done well for themselves, didn’t want anything to do with the new poorer arrivals.

At the same time, right wing bigots whipped up antisemitism against these new migrants. In 1902 the Bishop of Stepney said Jews were ‘swamping whole areas once populated by English people.’ In 1901 a popular anti-alien movement was formed called The British Brothers League. It had the support of local politicians, clergy and newspaper owners.

Similarly, Irish migration to Britain has taken place from the earliest recorded times. There is a specific context to Irish migration to Scotland that is beyond the scope of this piece. The most significant individual wave was when thousands of Irish immigrants arrived in the wake of the great hunger of 1845-49, during which 1.5 million people died of starvation and disease. They came to England to work on railways, in mills and the docks. There is an equally long history of anti-Irish racism in Britain that also complexly intersects with anti-Catholic sentiment and specific discrimination against Irish travellers – itself in a complex relationship with discrimination towards what has more recently come to be known as the Gypsy Roma and Traveller (GRT) community.

Again, it is not possible in this article to deal in detail with all the significant waves of migration to Britain over centuries or the different patterns of discrimination and racialization that took place. While different components of the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) community have a lengthy history of migration to Britain there is also a long history of discrimination. Today they are widely considered to be among the most socially excluded communities in the UK. They have a much lower life expectancy than the general population, with Traveller men and women living 10-12 years less than the wider population.

The Chinese community also merits a specific mention. Chinese immigration is also longstanding, both from the mainland and Hong Kong, and while anti-Chinese racism has received little attention outside the community it is also significant – and rose at the beginning of the Covid pandemic.

Finally, it would be a methodological error to ignore the most recent racialisation in Britain (and to some extent in Europe as a whole and the United States): the drive to create Islam as a race. It sounds absurd but in 2024 Islamophobia is a reactionary political force we must describe as racism. It is less likely to be targeted at Muslims who “pass” and it is sometimes directed at people who may not be Muslim at all – but to an extent both of those features are true of all forms of racism. Again, its evolution raises questions we don’t have the capacity to explore here – about racialisation, the rise of the nation state and the role of religion in politics – but it cannot be ignored in painting a picture of the dynamics of racism today.

State and far right racism

In 1968 the then Conservative MP Enoch Powell made his infamous and deeply racist ‘rivers of blood’ speech in which he blamed ‘coloured’ (sic) migration for all the ills of society. A key part of his target was the Race Relations Act Harold Wilson’s Labour government was about to introduce, focused on combating discrimination in housing and employment, especially for second generation immigrants. Powell was sacked from Edward Heath’s shadow cabinet for the speech.

One of the consequences of Powell’s vile rhetoric was the growth of physical attacks on people of South East Asian origin – known as ‘Paki bashing’ (sic) often by large groups of youth and often even targeted against young children. This was to continue as a significant phenomenon into the 1980s.

Heath had been elected as Prime Minister in 1970 and his government and the subsequent Labour governments during the rest of the decade were a fertile ground for the growth of fascism in Britain. The most prominent group on the far right during much of this time was the National Front. One of the issues over which they made a good deal of noise was the expulsion of Ugandan Asians by Idi Amin in 1972 and the fact that Heath ultimately allowed a large number to resettle in Britain (though he did try to resettle them instead in British overseas territories!). They also succeeded in recruiting many more members through this.

Shortly afterwards they shifted emphasis to trying to recruit more working-class members by taking up issues such as unemployment. They took more interest in electoral politics, too, fielding 554 candidates in the February 1974 general election, to ensure they could have a party election broadcast. They also continued to organise demonstrations including in areas with a significant Asian population such as in Bradford in 1976.

At the same time these developments were not accepted passively within the communities under attack. The second half of the 1970s in particular saw the growth of self-organisation amongst Asian Youth in different parts of Britain – increasingly under the common banner of Asian youth movements.

Part of the general dynamic at work was that older members of those communities felt that the best response to the growth of the far right was to keep your heads down, but this was not the view of young people many of whom experienced being beaten up on a regular basis. Another difference with earlier generations was that they had focused on creating organisations such as the Indian Workers Association, which tended to focus on the politics of where they had come from rather than racism and self-defence here.

More specific triggers were the 1976 murder of unarmed Sikh teenager Gurdip Singh Chaggar by Neo-Nazi skinheads in Southall West London and that of a Bangladeshi man, Altab Ali in Whitechapel in 1978. At best the state was indifferent to these attacks.

There was significant experience of bussing i.e. sending children to school in areas other than their own in cities like Bradford. This policy was high profile in the United States but also practiced by the Wilson government. High profile causes during the period included the ultimately successful Anwar Ditta Defence Campaign, over the right of Anwar Ditta bring her children to Britain from Pakistan.

The 1981 Bradford 12 case saw 12 young Asian men from Sikh, Muslim, Hindu and Christian backgrounds charged with conspiracy to cause explosives and endanger lives after making petrol bombs, which they never used, to defend their community against fascists. It took place in the context of the New Cross fire. Because the twelve were charged with conspiracy, the case was seen as a direct attempt by the state to criminalise political activists who had for five years been campaigning – through legal means – to defend their communities. The campaign exposed the failure of police both in Bradford and across the country to protect Black communities, and highlighted police racism, including the exposure of statements from the force that suggested, ‘Police officers must be prejudiced and discriminatory to do their job…’

There was strong support for Ireland’s right to self-determination amongst the Asian youth movements and a number of AYM members made visits to Belfast to learn from and draw closer links with the Republican movement. There was also solidarity with Irish Republican prisoners, with AYM Bradford sending two delegates to the North of England Irish Prisoner’s committee in relation to the imprisonment of Bobby Sands. Palestine was also a key issue especially in the context of 1982 when thousands of Palestinians were massacred in the Sabra and Shatilla refugee camps in Lebanon.

But while the Asian community was the major target of the far right, the Afro-Caribbean community was much more the target of the state. Sus laws were disproportionately used against them leading to uprisings in St Pauls and Bristol in 1980 and in Brixton, London; Toxteth, Liverpool; Handsworth, Birmingham; and Chapeltown, Leeds in 1981). There were also a series of murders by police – including Cherry Groce, Joy Gardener, Christopeher Alder, Cynthia Jarret, and Mark Duggan.

Anti-racist movements in different parts of the world take on different priorities, as they are in turn shaped by the nature of local reaction. In the UK, we have seen the growth of a view among both Asian and Afro-Caribbean youth ( and to a smaller extent also involving people from the Middle East) that favours an inclusive definition of the term Black. This coalesced around the insight that different types of racism in Britain today possess a shared structural basis that requires a cohesive radical strategy to uproot, which is distinct from the historical experience in the US where Black nationalism had its own social basis.

That is not to say that self-organised British anti-racism existed separate to the broader international context. The Soweto uprising, wherein a large number of schoolchildren in South Africa protested Apartheid on the 5 June 1976, and the Black Consciousness Movement more broadly there, also had a significant impact. At the time and in the next decades there was a flowering of self-organisation in Britain: The Labour Party Black Sections founded in 1983, the NALGO Black Workers Group in the 1980s, the first British TU that led to a TUC Black workers conference in 1993 all centrally using this definition of Black. Such a key political approach was also that adopted by the overwhelming majority of the radical left of those generations especially those of us involved in other movements of self organisation.

Back to today’s narrative

In mid-November 2023 the British Supreme Court handed down an unfavourable judgement to the government agreeing with an earlier Court of Appeal decision that asylum seekers sent by Britain to Rwanda were at real risk of refoulment – i.e. being sent ‘to a country where their life or freedom would be threatened on account of their race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, or they would be at real risk of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment.’

The judgement was based on detailed evidence already available concerning how refugees were treated by Rwanda – including those on a not entirely dissimilar scheme with Israel. Subsequently, more evidence about Rwanda’s appalling human rights record has come to light – including that the UK granted asylum to four peoe fleeing that county last year! But the people seeking asylum is not what most politicians want to focus on – it could undercut their hateful rhetoric.

Instead a new treaty with Rwanda was hurriedly signed and the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration bill) brought before parliament. At the heart of this deeply reactionary legislation is the extraordinary assumption that Westminster can change reality merely through how the majority of MPs vote– in this case that Rwanda is a safe country for refugees – when all evidence makes clear it is not.

The debate on the bill was presented as a major crisis for Sunak, who had pledged to ‘stop the boats’ as one of his five priorities for this year. Media speculation was rife that former Home Secretary Suella Braverman, sacked by the Prime Minister in November 2023, would take her revenge by rallying the Tory extreme right to defeat his Rwanda bill at its second reading.

Such a notion was at one level well founded – Braverman was deeply identified with the idea of offshoring asylum seekers to Rwanda – and while her removal from office was for other reasons, she was also extremely clear in her resignation letter she has no confidence Sunak is ruthless enough to take the necessary steps to effectively reduce all forms of migration.

Studying the letter she wrote after she left the Home Office, we see threads that have had less attention – particularly her focus on sovereignty and on Brexit. A*CR has always been clear that central to our longstanding opposition to Brexit is an understanding that a key part of its dynamic is the whipping up and use of racism – some but not all of which is targeted at migrants.

And there are undoubtedly deep divisions in the Tory party as it continues to fare disastrously in polls – many of which are related to issues such as ‘sovereignty’ that relate to the right-wing rhetoric of the Brexit debate. These divides were played out more clearly in the few days before the second reading with the self-described “five families” of right-wing factions on the one hand and the One Nation caucus on the other. In the end, the second reading was passed comfortably with no government MPs voting against it at this stage – though the PM far from is out of the woods as amendments are threatened at the third reading expected this January.

Opposition, what opposition

Why is this an issue of concern when 2024 will almost certainly see a general election and Sunak will most likely be replaced by Starmer in Number 10? Hasn’t Labour said they will not send asylum seekers to Rwanda? Yes, but their arguments are not fundamentally different from the Tories.

Interviewed at the time of Labour Party conference in October, Starmer’s response to Tory immigration policy was to say that the Rwanda scheme is ‘hugely expensive’ and he didn’t believe it ‘would reduce numbers’. In this, as well as the majority of contributions in the Parliamentary debate from Labour MPs, the idea that migration is an advantage to the host country is not even considered.

It is a vile indictment of twent- first century capitalism that criminal gangs make a fortune from desperate migrants, many of whom drown on voyages whether in the English Channel or the Mediterranean. But the way to deal with people smugglers is to tear down the border walls and fences that allow them to profit from this trade in death – not to talk about so called ‘solutions’ that criminalise those fleeing for their lives.

A*CR stands shoulder to shoulder with anyone who acts against the impact of the repressive immigration laws in Britain – or indeed anywhere else across the globe – and at the same time continue to argue that no one is illegal.Ccampaigning against injustice for migrants and the racism that feeds it needs to be an important priority for the entire left – whoever is in Number 10.

Timeline:

1894 First unsuccessful attempt to bring in legislation against Jewish immigration

1901 Royal Commission on Immigration, chaired by the Tory MP Major William Evans-Gordon

1901 British Brothers League formed

1905 Aliens Act passed.

Created immigration officers with the power to control who entered Britain. Refuse entry to those considered ‘undesirable’. Immigrants required to have a minimum of £5 on arrival

1906 Incoming Liberal government, which had earlier opposed the Act, enforced it

1914 Aliens Restriction Act passed in a few hours on the first day of World War

1919 ‘Temporary’ Aliens Restriction Act reinforced

1930s Jews fleeing Nazi persecution prevented from settling here unless they have a ‘sponsor’

1938 ‘Kristallnacht’ pogrom in Germany and Austria. Thousands of child refugees enter on the ‘kindertransport’. Parents are denied entry and perish at the Nazis’ hands.

1940s Jews reaching Britain’s shores during World Ward II often interned as ‘enemy aliens’. Some share detention camps with interned Nazis

1948 ‘Windrush’ ship brings 492 Jamaicans – the first major immigration from the Caribbean

1950 Labour Cabinet discusses ‘the means of preventing any further increase in the coloured population of this country

1958 Anti-immigration Tory MP Cyril Osborne declares: ‘It is time someone spoke out for the white man and I propose to do so’

1962 Labour Party opposes the Tories Commonwealth Immigrants Act limiting further immigration principally from the Caribbean

1965, 1968 Labour Government strengthens immigration laws against Commonwealth immigrants. Door remains wide open for white Britons who had emigrated to colonies, their children and grandchildren.

1968 British passport-holding Asians living in East Africa denied the right to settle in Britain

1971 New Immigration Act abolishes the categories of ‘aliens’ and ‘British subjects’. Creates new categories of patrials and non-patrials. Patrials (UK born grandparent – largely white) can continue to settle; non-patrials including Caribbean and Asian communities, formerly British subjects, can no longer settle. Dependants of immigrants arriving before ’71 Act is enforced have the right to settle but many are divided from their families for several years ‘proving’ their relationships for sceptical civil servants.

Primary immigration ended. Future immigration linked to work permits for specific periods.

1993-2004 Series of Asylum Acts tightening controls on potential asylum seekers

2004 Increasing European integration enables workers from many parts of Europe, including eastern Europe, to seek temporary work in different EC countries, including the UK. Residence rights possible after repeated renewals of work permits.

Further reading

https://web.archive.org/web/20071214001603/http://www.channel4.com/culture/microsites/O/origination/immigration_aliens_landed.html

https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/wmr-2022-interactive/

https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/immigration-by-country

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/12/16/key-facts-about-recent-trends-in-global-migration/

https://www.freedomfromtorture.org/news/windrush-and-the-hostile-environment-all-you-need-to-know

https://www.spelthorne.gov.uk/article/19678/A-timeline-of-black-history-in-Britain#:~:text=1555%20%2D%20A%20group%20of%20African,slaves%2C%20servants%20and%20seamen%20increases.

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/history-black-people-britain

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/histories/black-history/

https://www.ourmigrationstory.org.uk/oms/jewish-immigration-and-the-aliens-act-1905

Asian Youth Movements in the UK: history and legacy – House of Lords Library (parliament.uk)

Recollections on the Asian Youth Movements that emerged in the 1970s – Institute of Race Relations (irr.org.uk)

Ramamurthy-RacismSelfDefence(VoR).pdf (shu.ac.uk)

Black Britannia: The Asian Youth Movements That Demonstrated the Potential of Anti-Racist Solidarity | Novara Media