Disability Pride Month celebrates people with disabilities, their identities, their culture, and their contributions to society. It also seeks to change the way people think about and define disability, to end the stigma of disability, and to promote the belief that disability is a natural part of human diversity in which people living with disabilities can celebrate and take pride. It is a chance for people with disabilities to come together and celebrate being themselves, no matter their differences. It is also a chance to raise awareness of the challenges they still face every day to be treated equally.”1

Within this article, as someone who has witnessed the rise and fall of the British Disabled People’s Movement, I want to unpack some of the contradictions, tensions, and political differences, that have existed within disability politics, cultural formations, and identities. My aim is to express political concerns with regard to the road that has been travelled down since the late 1960s, and to question the possible next stretch of the journey.

Pride by Johnny Crescendo

Pride is something in your soul

Pride is somewhere you are in control

Pride is the peace within that finally makes you whole

Celebrate your difference with pride

Pride in yourself is bound to set you free

Pride in who you are, a person just like me

Pride and self-respect and gentle dignity

No one can take away your pride

Pride can make you strong

Pride’s the key that unlocks the doors

to the rooms where we belong

Pride is our destiny and where we all came from

Turn around embrace your pride

Pride can make you equal without your liberty

Pride can give its freedom to a prisoner like me

Pride is always with you wherever you may be

Once won you’ll never lose your pride

Pride is a rocky road that’s straight and doesn’t bend

Pride’s a path you follow

Pride’s your closest friend

It has to be acknowledged from the outset that the issue of disability – from political and social perspectives – is without doubt one of the most contested arenas there is. There is no overall agreement as to what disability is, or where it can be located. This article cannot do justice to all the complexities involved, therefore, I would like to signpost towards my book, Disability Praxis, which goes into greater depths, and my forthcoming book, Coming to terms with disability, to be published by Resistance Books, which offer insights into my theoretical writing around disability.2

Disability, culture and identities

What I want to do is unpack the ideas that are said to be behind what is called Disability Pride, and offer an alternative political and cultural take. To undertake this task, it is necessary to present the framework of the argument I work within in relation to disabled people’s emancipation struggle. As already stated, It is not my attention to provide a detailed account but rather to signpost issues that have assisted me to construct the argument. I am presenting my approach towards disability, and then attempting to relate this to various associated concepts such as: disability politics, disability culture, and, finally, disability pride and identity politics.

Where should we begin? I want to recall how the British Disabled People’s Movement came into being and its central platform. The starting point for this new social movement was the coming together of a small group of physically impaired people. Next year, 2026, it will be fifty years since the founding conference of the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS).3 In the first issue of their organ, Disability Challenge, they wrote:

“We do not organise because we are people first, nor because we are physically impaired. We organise because of the way society disables physically impaired people, because this must be resisted and overcome. The Union unashamedly identifies itself as an organisation of physically impaired people, and encourages its members to seek pride in ourselves, in all aspects of what we are. It is the Union’s social definition of disability which has enabled us to cut out much of the nonsense, the shame and the confusion from our minds “.4

Over the years I believe this message has become distorted, confused and in some quarters, lost. There is a need to unpack it because it is at the core of my overall argument. In this one statement lies five vital elements that underpin disability politics in my opinion:

- The central aim is resist and overcome the way in which society disables people with impairments.

- The driving force is not the fact we are people and that issues surrounding impairment realities and disability are simply appendages; the motivation is changing the social situation encountered as exclusions and marginalisation.

- The commonality behind addressing disability is in the collective action to resist and overcome the social restrictions which are imposed on top of our impairments.

- Part of this collective action involves rejecting dominant ideologies and culture which denies people with impairments’ self-determination which includes the ability to self-define our identities and acknowledge our own social worth – i.e. “seeking pride in ourselves”.

- The centrality of employing a social approach to defining disability.

The latter two elements relate directly to the differing perspectives on disability culture and pride. Before progressing and linking these five elements together, certain historical facts need stating. It took UPIAS four years of painstaking discussion to formulise their social interpretation of disability.5 Mike Oliver informs us that:

“Starting from the work of Harris (1971) and her national survey of disabled people, a threefold distinction of impairment, disability and handicap was developed. Following various discussions and refinements, a more sophisticated scheme was advanced by Wood (1981) and this was accepted by the World Health Organization as the basis for classifying illness, disease and disability. However, these definitions have not received universal acceptance, particularly amongst disabled people and their organisations.”6

Much of UPIAS’ early thinking featured subverting the triad definition of disability introduced by Amelia Harris. Vic Finkelstein/UPIAS write:

“…In our view, it is society which disables physically impaired people. Disability is something imposed on top of our impairments by the way we are unnecessarily isolated and excluded from full participation in society. Disabled people are therefore an oppressed group in society. To understand this, it is necessary to grasp the distinction between the physical impairment and the social situation, called ‘disability’, of people with such impairment. Thus we define impairment as lacking part of or all of a limb, or having a defective limb, organ or mechanism of the body; and disability as the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by a contemporary social organisation which takes no or little account of people who have physical impairments and thus excludes them from participation in the mainstream of social activities. Physical disability is therefore a particular form of social oppression. (These definitions refer back to those of Amelia Harris, but differ from them significantly).”7

I was involved in these early discussions and questioned the wisdom of simply adopting Harris’ definition of impairment and I remain critical despite accepting the need to employ it due to the fact that no other term has been developed to satisfactorily replace it. My critical stance has a number of features that have implications for how I believe disability theory, culture, and politics developed and, as a result, has had detrimental consequences for the positioning of non-conforming bodies and minds. To reveal these features, I want to raise how Finkelstein justified accepting Harris’ impairment definition. He wrote:

“I understand we are referring to the physical abnormality (or damage) in the condition of the individual’s body. This may have resulted from illness, accident, or genetical reasons. Physical impairment is usually what we mean when we talk about “medical” diagnoses, such as multiple sclerosis, left lower limb amputation, etc. The point being that it is the task of medical science to describe these conditions accurately. The alleviation of problems involving physical impairment falls within the realm of medicine.”8

The first thing that needs recalling is the fact UPIAS’ social interpretation of disability was only applied to people, in the first instance, who were considered physically impaired. Given this, in the majority of circumstances, their ‘impairments’ had arisen from illness, severe injury, or genetic conditions. I would refer to this as a material fact; for example, my brain was ‘damaged’ at birth resulting in me being ‘diagnosed’ as having cerebral palsy. The problem is that this is not the whole story because my, or any other diagnoses, is not solely based on material facts but are at the same time overlaid with medical and social ideological constructs. Finkelstein’s first sentence quoted above illustrates how easy it is to conflate the material and ideological: hence, ‘we are referring to the physical abnormality (or damage) in the condition of the individual’s body’ (Emphasis added – BWF ). To describe the condition as a ‘physical abnormality’ immediately accepts the idea that there are standard or ‘normal’ (sic) bodies and minds. In these circumstances, any physically impairment becomes evaluated as a deviation from the norm and the nonconformity judged in negative terms.

In a UPIAS circular, I raised objections to the term, ‘physically impaired’ because in my view the social meaning attached to ‘impaired’ was of something considered “flawed”. As a twenty two year old, I rejected seeing myself as ‘physically flawed’ (sic). Over time, as Colin Barnes noted, the Movement used ‘impairment’ as a neutral term; however this was against the power of dominant meanings associated with all terms, relating to disability, and therefore in my opinion it remains a problematic unresolved issue.9 I believe there is a general disquiet outside of the community of scholar activists around the understanding of how the terms, ‘people with impairments’ and ‘disabled people’ relate to each other. This has been a feature of the tensions and contradictions surrounding the various perspectives on disability culture and disability pride.

Another feature I wish to note in passing is that in the Finkelstein quotation above, he writes ‘….it is the task of medical science to describe these conditions accurately. The alleviation of problems involving physical impairment falls within the realm of medicine.’ This ignores the point I made earlier about the ideological elements found in medicine; in addition I believe it misdirects the role played by what Mike Oliver described as ‘the individual tragedy model of disability’ as I will demonstrate in due course. Finally, this neutral stance on medical science opened the door to criticism from disabled feminists such as Liz Crow and academics like Bill Hughes and Kevin Patterson who argue the social approach “leaves the impaired body in the exclusive jurisdiction of medical hermeneutics.”10 Unfortunately, there is a grain of truth in this, but not necessary in the ways they are presented.11

As I imply in Disability Praxis, the positioning of impairment realities within radical disability politics based upon the social interpretation/ model, became problematic around three major issues. The first being how all sides within debates came to (mis)understand UPIAS’ reasoning behind the breaking of the causal link between impairment [their existence and realities] and disability [the oppressive situation encountered]. Unlike dominant thinking, UPIAS rejected seeing an individual’s impairment as the direct cause of their social disadvantage. Secondly, as a result of seeing society as being ‘the cause of disability’, radical disability politics shifted the focus onto creating social change within society with an emphasis on policies, procedures, and practices. The site of struggle around ‘unequal and different treatment’ on a daily basis is not just in terms of encountering discrimination, but also the impact of facing differing forms of oppression, as well as managing ill health and/or impairment realities in disablist cultures and environments, was left floating. What this led to was less political disabled people looking for more immediate and accommodating solutions which found a home in the accommodationist policies of the mid-1990s around obtaining civil rights and being viewed as equal citizens. We even witnessed certain sections of the disabled centre-right working with charities in a neoliberal hybrid movement, alongside New Labour, to achieve equality by 2025!12

The third major issue was the inadequate way the social interpretation/ model was extended to cover groups beyond those with physical impairments. Apart from Oliver’s advice to identify specific disabling barriers for particular groups of disabled people, little attention was or is currently paid beyond talking about ‘inclusion’ in the abstract.13 This is why I call into question the very existence of a social movement into the 21st century.14 It is also, in my opinion, that this contributed to the uneasy and sometimes confused discussions between the neurodiverse, Deaf, and Mental Health, and disabled people’s communities.15

Steve Graby (in 2015) wrote:

Reactions to [the social model] from the survivor movement have been mixed. Some survivor activists have welcomed the social model because of its attribution of disability to social exclusion and oppression, rather than to something inherent in individuals. For many, however, the concept of impairment as distinct from disability has been a major stumbling block, with some survivor activists arguing that to categorise mental distress as an impairment is to return to the medical and pathological models of ‘mental illness’ from which their movement seeks to escape ….. Other survivor activists …. regard the ‘impairment debate’ as divisive and detrimental to the movement, arguing that survivors are ‘disabled’ by the stigma and material oppression they experience, whether or not they are regarded as having an impairment. This does, however, raise the question of the limits of the term ‘disability’ …. if disability is defined solely as oppression and impairment is not regarded as a prerequisite for it, many other groups could be considered ‘disabled’ who would not ordinarily be defined as such.”16

This quotation links together a number of issues: how ‘impairment’ is understood and why specific self-evaluations lead to distancing from or acceptance of social model related definitions. It also brings back into focus how disability, disablement, and disablism are made sense of. Finally, taken altogether, it does raise a question regarding which groups could or would want to be considered ‘disabled.’

Having outlined crucial historical facts, let us return to how disability politics emerged and the basis for the social interpretation of disability. This is how UPIAS summed this up:

“For instance, it follows from this view [social interpretation towards disability – BWF] that poverty does not arise because of the physical inability to work and earn a living – but because we are prevented from working by the way work is organised in this society. It is not because of our bodies that we are immobile – but because of the way that the means of mobility is organised that we cannot move. It is not because of our bodies that we live in unsuitable housing – but it is because of the way that our society organises its housing provision that we get stuck in badly designed dwellings. It is not because of our bodies that we get carted off into segregated residential institutions – but because of the way help is organised. It is not because of our bodies that we are segregated into special schools – but because of the way education is organised. It is not because we are physically impaired that we are rejected by society – but because of the way social relationships are organised that we are placed beyond friendships, marriages and public life. Disability is not something we possess, but something our society possesses.”17

What this description does is locate ‘the problem of disability’ within the social organisation of society and not resulting from an individual’s impairment.

I believe UPIAS’s social approach towards disability does have certain weaknesses as indicated, but these do not invalidate the overall argument. In my opinion it is inadequate to describe disability as being discrimination and that the encountered discrimination can be viewed as being the only aspect of disabled people’s experience of social oppression. Disabled academic Mike Oliver, through his social model of disability alongside other disabled academics and activists have widened our understanding that disablement is more than just the denial of participation in societal social activities; it includes all aspects of social relations determined at both the macro and micro levels of society. I have questioned UPIAS’s view of how it saw our oppression as stemming from disabled people’s experience of ‘not being taken into account’ and suggested that it is in fact marginalisation, thereby not being ‘taken into account’ i.e., included.

While dominant ideologies and practice prevail, the public gaze and social policy will continue to have a focus upon the nature and degree of an individual person’s impairment(s). A focus on ‘barrier removal’ alone is therefore inadequate.

My starting point is to see disability as the representation of an oppressive social situation. I sought to frame concepts – politics, praxis, culture, rights, etc. – in terms of a dialectical relationship between what they represent and disability. A dialectical relationship refers to the standing of two objects in direct antagonistic opposition to each other. Hence, I wrote:

“Disability politics, for example, signifies politics that stand in opposition to the encountered social restrictions and oppression (disablement) faced by disabled people. These dialectical relationships stem from the desire of disabled people to free themselves from oppressive social relations. This desire is created by what is referred to as the ‘dialectics of disability’ – that is, the antagonistic interactions that exist within capitalist societies for disabled and non-disabled people.”18

To support this argument, I referred to Costello who stated:

“While the capitalist economy as such rejected disabled people as unproductive, the state institutions created and reinforced negative social attitudes towards disability. Capitalist society had relegated disabled people to the most negative status of poverty and isolation. These negative attitudes were used to justify disadvantageous social positions, which strengthened the attitudes themselves. Institutions and attitudes were and are in a constant interplay with one another, feeding back into and altering each other. In Marxist terms, they interact dialectically.”19

I went on to state that:

“The word ‘dialectic’ has a number of meanings, including a description of a method of argument that systematically weighs contradictory facts or ideas with a view to seeking a resolution in terms of their real or apparent contradictions. Within Marxist thinking, dialectics are seen as forging a process of change through the conflict of opposing forces, where the interplay between them can produce a transformed relationship. The issue of the dialectics of disability is of importance to disability politics because they reveal the antagonistic relations of various processes disabled people are forced to negotiate.”20

A key aspect of the disability dialectic is the fact that disabled people want to be part of a society that has sought to exclude or marginalise the majority of them. It is the disability dialectic that I see as a major influence on differing perspectives around the emancipation of disabled people. To a degree the social model of disability helps us understand how we could “transform” the way disability is understood and make interventions which could change existing social relations within structures, systems and cultures of society. However, it does wobble when it comes to addressing the root cause of disablement in certain ‘interpretations’. The less radical interpretations underplay the “nature” of capitalist society and its “values”.

The radical interpretation does see capitalist society’s social relations with people with impairments as the root cause of their oppression. With the social model shifting the focus away from our bodies and minds onto the organisation of society, it was considered as a direct threat to capitalism itself, whose existence depended for most of its life on exploiting individual bodies and minds.

Capitalism’s social relations however are not static, they are historically specific, and capable of transforming, therefore the nature of disablement changes as well. Among disabled activists there are political divisions below the surface which relate to both the structural nature of disablement and the consequences that arise. The centre-right view the structures of disablement as relatively static – “we encounter the same disabling barriers we’ve always faced.” There is also a tendency which has not only adopted the American ‘rights’ focused agenda, butalso view disabled people’s social exclusions as stemming from ‘ableism’. An early definition of ableism came from Rauscher and McClintock, and is understood unidirectionally to mean:

[…] A pervasive system of discrimination and exclusion that oppresses people who have mental, emotional, and physical disabilities […] Deeply rooted beliefs about health, productivity, beauty and the value of human life, perpetuated by the public and private media, combine to create an environment that is often hostile….” 21

Secondly, it is wholly inadequate to characterise what I consider to be sites of struggle – health, productivity, beauty and the value of human life – simply as ‘deeply rooted beliefs’ [also articulated as cultural in form] which are then viewed as combining “to create an environment that is often hostile […].” An important academic in theorising ableism has been Fiona Kumar Campbell.

Campbell is quoted as writing:

“Summarised by Campbell (2001, 44) Ableism refers to; […] A network of beliefs processes and practices that produces a particular kind of self and body (the corporeal standard) that is projected as the perfect, species typical and therefore essential and fully human. Disability then is cast as a diminished state of being human. Writing today (2013) I add additional caveats to this definition: ‘The ableist corporeal configuration is immutable, permanent and laden with qualities of perfectionism or the enhancement imperative orientated towards an atomistic improvability’. Sentiency applies to not just the human but the ‘animal’ world (see Taylor, 2012). A feature of modernity is its focus on the regulation of bodies, resulting in what Bryan Turner (1992) calls a ‘somatic society’ wherein the body has become a central site of consumption and contestation.”22

None of the cultural or aesthetical issues raised here are absent from a historical materialist analysis of how they both influenced and legitimated the development of disablism. Likewise, the regulation of bodies was a crucial factor in capitalist development. Much of the articulation of ableism is ahistoric, and in my view, incorrectly places ‘outcomes’ of capitalist modes of thought and practices as ‘causes’. I do not accept that it is a useful concept, nor do I regard ‘ableism’ to be either a network or system floating around within capitalism. Its introduction has distorted how disabled people’s experience of oppression and encountered discrimination is ‘made sense of’ within social and political terrains. I would argue that its arrival coincided with shifts within dominant thinking around disability and its hegemonic status.

Elsewhere, I have stated:

“A number of disabled scholar activists, led by David Pfeiffer, rounded upon the WHO’s ICIDH and early drafts of what was known as ‘ICIDH-2’. Feeling under increased pressure, the WHO in 2001 adopted the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Within the World Health Organization’s ICF, the word ‘disabilities’ is used as an umbrella term to cover impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. […]. Interestingly, Marks argues that the ICF ‘seeks to develop the conception that “mind, body, and environment are not easily separable but rather mutually constitute each other in complex ways.’ The upshot of this shift is that whereas within the ICIDH ‘social barriers’ were reduced to simply being the consequence of the impact of an impairment, including the loss or reduction of functionality, what the ICF does is to conceive ‘disability’ as ‘a compound phenomenon’ where the individual and social elements are viewed as integral.”23

In my book, I touch on the misunderstanding of the crucial framing of disability as a social situation – the ways particular groups of people find themselves excluded from or marginalised within mainstream social activities – being ‘made unable’ to participate. Breaking the causal link however does not signify the absence of impairment reality in the social approach. The negative or oppressive interactions that take place between specific groups of disabled people and given environments arise from the social organisation of capitalist societies, including how ‘disability’ is ideologically defined and managed as the absence of normality. Within these negative or oppressive interactions, personal consequences obviously arise because both sides influence the outcome of particular interactions. There is a need to understand the relational nature of the ‘bigger picture’ – the collective encounters mainly at a macro level – and the implications for personal experience at a micro level. This relational aspect does not exist within dominant thought when ‘disability’ is viewed as stemming from ‘impairment effects.’

On paper, the World Health Organisation’s ICF appears to share this ‘understanding’ as it states:

“The functioning of an individual in a specific domain reflects an interaction between the health condition and the contextual: environmental and personal factors. There is a complex, dynamic and often unpredictable relationship among these entities. The interactions work in two directions […]. To make simple linear inferences from one entity to another is incorrect; e.g., to infer overall disability from a diagnosis, activity limitations from one or more impairments, or a participation restriction from one or more limitations. It is important to collect data on these entities independently and then explore associations between them empirically.”24 However, the ICF sees ‘disabilities’ as being an umbrella term covering, “impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. It denotes the negative aspects of the interaction between an individual (with a health condition) and that individual’s contextual factors (environmental and personal factors).”25

How is this presented? It is only when one unpacks each component that we see behind the ideological masking. Thus:

Body functions – The physiological functions of body systems (including psychological functions).

Body structures – Anatomical parts of the body such as organs, limbs and their components.

Impairments – Problems in body function and structure such as significant deviation or loss.

Activity – The execution of a task or action by an individual.

Participation – Involvement in a life situation. Activity limitations – difficulties an individual may have in executing activities.

Participation restrictions – Problems an individual may experience in involvement in life situations.

Environmental factors – The physical, social and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives. These are either barriers to or facilitators of the person’s functioning. (The italics added to reveal traditional judgemental language– BWF).

It should be noted that the WHO considers the language employed here is ‘neutral’, however, a raft of scholar activists have contested this. Gramsci’s approach towards ‘common sense’ enables us to reveal how the ICF retains the overlaying of ideological meaning.26

Given the crisis of capitalism and the global challenge from disabled people, I believe it did not serve Capital to retain the hegemonic power of disability ‘as a personal tragedy’. Neoliberalism was anti-welfare state and promoted self-reliance. Enter the notion of wanting to “See the Person not the Disability”, but within the context of the disability dialectic, this threw up fresh tensions and contradictions.

The crisis of capitalism: the rise of Janus politics and demise of radical disability politics

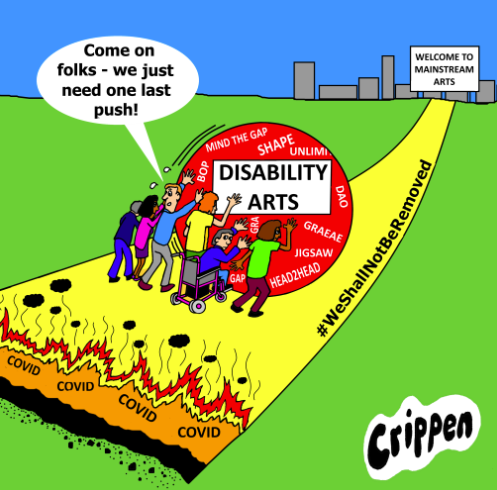

In Disability Praxis I write about the fact that the nature of disablement is changing and how the decline in the radicalism of British disability politics was picked up by some of the Movement’s founders during the 1990s. Vic Finkelstein, for example, was critical of the focus on obtaining ‘anti-discrimination legislation’, and how issues such as independent living, direct payments and rights were being viewed as detached from the social approach towards disability. It was argued that the emerging ‘rights approach’ not only shifted the focus away from the original social one, but it also paved the way for sections of the Movement to collude with New Labour’s neoliberal ‘rights with responsibilities’ mantra.27 The term ‘Janus politics’ was employed to describe looking back to the concepts of the old Disabled People’s Movement, but emptying them of their original radical meanings, and replace them with reformist ideas that sat comfortably with neoliberal policies which furthered self-reliance and individualism.28

The adoption of Janus politics gave rise to a new ‘Disability Movement’, comprised of the traditional disability charities and market-orientated disabled people’s organisations. This produced a sharp distinction between the broad ‘politics of disability’ that exists within society, and disability politics which have been articulated in this article as the roots of praxis coming from the historical materialists’ approach to defining disability. By acknowledging the divisions that emerged within the Movement, it is possible to ask to what extent disabled people and their organisations were ill equipped for the Age of Austerity – did they miss vital clues that might have ‘armed’ them better?

The mid-1990s onwards saw a tendency emerge that focused on accommodating to the service sector and solely engaging with protecting disabled people from ‘discrimination’ and seeking to promote a better life through exercising rights and obtaining social inclusion within society. The passing of the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) was viewed as a victory; however, Finkelstein addressed this when he wrote, ‘The ideological problem facing the […] movement […] from the 1990s onwards was whether the social model […] was still relevant in guiding our struggle or whether social changes had advanced so far that the original model no longer reflected the social context in which it had been created?’29

By shifting the focus entirely on ‘Rights’, the Movement lost sight of the bigger picture, which halted any critical evaluation of capitalist society. As a result, the ‘leadership’, through the British Council of Disabled People (BCODP)and Rights Now, tied the Movement to a reformist agenda which centred primarily upon ‘Rights’ as the key to unlocking the disabling barriers at the micro level of society. On a personal and political level, as a leading activist, I am implicated in the direction of travel taken because as vice-chair, and then chair of BCODP, I saw the ‘rights campaign’ as being a means to an end, not an end in itself. I held the view that the passage of the DDA was a political defeat and, as Finkelstein had predicted, it drove a wedge through the Movement which proved to be a mortal blow.

The Movement began to lose its influence and direction, allowing New Labour to isolate large sections of it; whilst incorporating others into a revisionist agenda. Not only did the Movement become a rump of its former self and, over time, lost sight of its original aims which sought a holistic approach towards social change. What this means is the Movement offered no leadership to disabled people because it became trapped within a static time warp until it fizzled out.

This political demise also had its impact upon the cultural terrain. The radical perspective of developing a disability culture was based upon the argument that it is society’s social relations that transform people with impairments into disabled people. Therefore, it is the collective experience of social oppression, and acknowledgement of this fact which gives rise to the view that the term disabled people is a political identity.

This of course creates tensions and confusion because the term, ‘disabled people’ has been employed as a category within social and legal policies:

‘A person has a disability if:

- They have a physical or mental impairment, and

- the impairment has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on the person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.’30

This stands in sharp contrast with Oliver’s criteria from 1999:

“For me disabled people are defined in terms of three criteria;

(i) they have an impairment;

(ii) they experience oppression as a consequence; and

(iii) they identify themselves as a disabled person.

Using the generic term [disabled people] does not mean that I do not recognise differences in experience within the group but that in exploring this we should start from the ways oppression differentially impacts on different groups of people rather than with differences in experience among individuals with different impairments.”31

What I have suggested is that on a daily basis disabled people are confronted with a category, presented as an identity, imposed by society; and a political identity being forged by disability politics and culture. Many disabled people are uncomfortable with this dualistic approach because it can come across as suggesting an abandonment of certain sections of the disabled community because they remain “unconscious” of their own social oppression but I believe this misinterprets what is being implied here. Let us walk through this dualistic approach as I call it.

Dominant ideologies and practices are connected to the reductive understanding that ‘the capabilities and limitations of the body determine the state and development of society and social relations’.32 Hence the focus is on the body and its social worth.

Within the ‘individualistic approach towards disability’, an individual is a disabled person because of the severity of their impaired functioning; whereas the social approach sees an individual as a disabled person because they are part of a collective social group that is disabled by society. The social approach also recognises that disabled people do not constitute a homogeneous, coherent, and stable group; because, as Barnes, et al state, ‘disability does not have a universal character’ and disabled people do not easily fit into any coherent category (of explanation or experience).33 Alongside recognising acknowledging the diversity of disabled people’s lived experiences, too often the intersectional nature of experiencing more than one form of oppression is underplayed or ignored.

Let us be clear as to what Oliver’s methodology is about here, the focus is upon exploring the nature of oppression as experienced by differing groups of disabled people, not their personal experience which could be shaped by a thousand and one things. To embrace the political collective identity of ‘disabled people’ it is necessary to acknowledge one’s impairment, as a consequence of having an impairment one can be subjected to social oppression – unequal and differential treatment -and that this awareness leads to self-identification as a disabled person within a socio-political context.

Finkelstein suggested that an understanding of the psychology of disability must start from the principle that: “[…] we make sense of our world according to the way we experience it […]. If disabled people are denied access to mainstreamed social activities, we will not only have different experiences to that of our able-bodied peers but we will interpret the world differently; we will see it, think about it, have feelings about it and talk about it differently.”34

The question is, however, from what standpoint should this psychological experience be interpreted?

Finkelstein argued: “[that as most things are] made sense of through the lived experiences of non-disabled people, this means the development of an understanding of the psychology of disability has been prevented. Disabled people’s own interpretations of the world have been ignored, not allowed to develop or simply denied because they are regarded as subjective and therefore not valid.”35

This is one of the reasons why I link the concept of internalised oppression with the dialectics of disability and the paradoxical relationships that exist for disabled people as a result. It is also why I believe disability culture is important; although the failure to address the impact of how and why disabled people have had their impairments used against them has led to the idealist distortions within the promoting of disability politics and culture. The radical social approach towards disability was right to break the causal link between impairment and disability, but in so doing, neglected the significance of the fact that as most things are ‘made sense of’ through the lived experiences of non-disabled people, including the absence of living with significant impairments.

The underplaying of linking the concept of internalised oppression with the dialectics of disability means disability politics in the hands of the idealists has resulted in the rejection of the breaking the causal link between impairment and disability, situating and presenting impairment reality in terms of ‘embodiment’, and replacing the materialist understanding of disablism with accounts of ‘ableism’. This shift in disability politics over the last thirty years has created troubled waters. The shifts, as noted, also relate to shifts within mainstream politics as well. As one disabled activist put it to me: “The barriers to true independent living, and how we experience the world, undoubtedly inform our experiences! Yet oppression is our real lived experience [of] the threat of institutional care, how we are educated and approaches towards our health. [This treatment] realises the oppression of our autonomy, our voice and diverse range of experiences.”

Here lies the essence of the troubled waters. The denial of disabled people’s autonomy, their collective voice and promotion of their diverse range of experiences has led to their lives and ‘selves’ being externally defined and controlled.

The last thirty years has seen the reversing of the positive gains made by disabled people. Neoliberal social and economic policies have ensured that the impaired body has become a site of struggle in part through commodification relating to ‘Social Care’ (sic) and employment, on the one hand, and the promotion of self-reliance and eugenics based values, on the other. Just as the false dream of ‘full civil and human rights’ was being embraced, the harsh realities of the age of austerity came along to turn the dream into a nightmare.

The road to emancipation or containment?

What are some of the consequences from the demise of the global and national disabled people’s social movements? The imported American cultural and idealist views fused with the rights agenda and the bio-psycho social model as represented by the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning (ICF), and United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (sic) Against this backdrop, the radical ideas which informed both disability politics and culture were abandoned. As such the only visible way ‘to make sense of the world’ was to work with and against the lived experiences of non-disabled people.36 As a consequence, the ‘identity politics’ coming from the USA operate from an idealist and individualised basis. Thus, ‘disability pride’ becomes the articulation of what I call a ‘reverse mirror’ which sets out to turn ‘bad’, ‘negative’, ‘unacceptable’, ways of viewing and treating people and their ‘disabilities’ (sic) into ‘good’, ‘positive’ and ‘acceptable’ ones.

Recently, I saw a button badge that read: “Disability is not a bad word”. Purely on a linguistical level, this is a nonsense because the pre-fix ‘dis’ means ‘without’ or ‘lacking’. Here we have a form of assimilation where the disability dialectic shifts to secure the status quo despite the appearance of creating a new ‘positive’ identity/image. Does this ‘celebrate disability’ approach address the real issues around impairment production, capitalist social relations, and the need for a transformative society? I would argue that the real issues become hidden within the ‘reverse mirror’ which sees reflected the rejection of ‘blaming the disabled’ (sic) and switching things so that the blame falls on the bogey ‘able’ instead.

During a recent dialogue on Facebook concerning a Canadian designed Disability Pride flag, Barbara Lisicki, (co-founder of the disabled people’s Direct Action Network and aka Wanda Barbara), wrote:

“[…] How can a set of coloured stripes with each one designated to represent a specific impairment group be anything other than medical model drivel? Whatever you think of Disability Pride as an idea – and it isn’t a purely US import – this trite nonsense isn’t it.

Many of us talked about disability pride in the ‘90’s as being connected with disability arts & culture and developing an identity that acknowledged us as equal and valid in society (we clearly were not accepted as such in any mainstream sense) but we had to insist on our realities being acknowledged, organised for and understood as inextricably bound up with the political struggle for ‘rights not charity’.

Listen to the lyrics of the song Pride by Johnny Crescendo (aka Alan Holdsworth)

‘Pride is something in your soul

Pride is somewhere you are in control…’

With a powerful participatory chorus of ‘Proud, Angry and Strong’

We had a thriving political, arts and cultural presence that did actually foster solidarity, a collective sense of needing to be to out in the world, participating, challenging and fighting for major change.”

I believe during the exchange between us, Barbara had misunderstood the distinction I had made. I responded by saying, “Barbara, I said the American concept of Disability Pride, because I align with the idea of a disability culture being about developing our own expression and articulation of the collective experience of living in a disabling world and fighting back. […] The American version appears to simply turn the negative and oppressive appraisals on their heads. What do they believe the word ‘disability’ means? It’s a nonsense approach which does pander towards neoliberalism.”37

Here is where I require a tin hat because I want to forward the view that this is a by-product of internalised oppression. As Barbara says, “we had to insist on our realities being acknowledged” however she could have added: on our terms. Among certain layers of disabled communities, there are people who both internalise, while at the same time, reject how they are both seen and treated. Many react to this dialectical situation by looking for ‘acceptance’ and social role valorisation.38 I see this as an accommodating perspective whereby ‘disability’ is portrayed as a natural human experience. Using whatever definition, this is complete idealist nonsense because most impairment results from harmful human interventions. How any individual views their own impairment and/or bodily nonconformity and subsequent relations with them is a matter of personal decision making. It is possible to ‘accept’ one’s impairment realities whilst at the same time have a myriad of opinion on the existence of them. I have always opposed both nondisabled and disabled people imposing impairment constructions – i.e., positive images or representations of ‘disability’. Disability arts and culture was about telling it how it is; not enforcing some happy-clappy normalising oppressive whitewash.

The watering down and changing face of disability politics, art and culture

The lack of attention paid to impairment reality, especially in relation to living in a disablist society, means that disability politics only promoted a partial understanding of disability culture – the lived experience of ‘making sense of’, living within and seeking to resist, a disabling society. Art production is part of this because I see disability art as an agent of resistance and the representation of disabled people in opposition to disability. It is a tool to assist disabled people ‘to make sense of’ the world through their experiences which includes facing oppression, but also impairment reality because the body is a site of struggle.

My issue here is that everything I have written about makes the present ‘world of disability art’ problematic for a number of reasons.

The dual identity, the conflation of impairment reality and disability again, the de-politicisation of disabled communities, the ‘celebrate disability’ cultural promotion, all contribute to the uncertainty as to what disability art is in today’s world. Much of what I find troubling I have related to the question of social and political consciousness. When a person with cerebral palsy, for example, paints a vase of flowers; is this no different to someone without an impairment undertaking the painting? I am not focusing so much on the functioning side of things, but rather what the artist brings to the canvas. Recalling the question of paradoxical relationships and the psychology of disability, maybe there is more to the sites of struggle disabled people battle on than meets the ‘eye’.

All of these issues, I believe, coalesce to provide some insights into why the global shift to the right has had such a negative impact upon radical disability politics and subsequent articulations around culture and identity. There has been a retreat into safe havens and a clamour for ‘acceptance’ through a form of stale identity politics. Here is the platform for today’s ‘disability pride’. Sadly, this accommodational drift does nothing to assist in the resistance to the current attacks on disabled people. There is a fork in the road, one leads to emancipation via forging a new disability praxis, the other leads to a happy-clappy future of containment at best.

Here are the concepts I employ:

I have put together key concepts and definitions based upon the social approach towards disability as applied to my writing. The definitions of disability politics, culture, and art all operate through a juxtaposition of opposing forces; for example, disability politics are viewed as ‘politics standing in opposition to disabling social restrictions’.

Key concepts

Disability = the imposition of social restrictions on top of impairment reality created from the structures, systems, values, culture and practice of given societies which creates an oppressive situation – exclusion and/or marginalisation. Disability therefore is an encountered oppressive social situation.

Disablement = is the negative result of economic, political, social, and ideological influences on the structures, systems, values, culture and practice of given societies as experienced by disabled people.

Disablism = the acceptance and promotion of ideas and practice associated with dominant ideologies that present ‘disability’ as the absence of normality, a state of inferiority and the cause of perceived lack of social worth found within an individual – e.g. a burden on society, lacking in capacity to fulfil accepted and excepted tasks.

The following definitions work through the dialectical relationship between disability (social restriction) and emancipatory engagement

Disability rights = sets of demands by disabled people to further self-determination and in opposition to their social oppression. Not simply the legal protection of their civil and human rights.

Disability culture = the cultures developed by disabled people in their struggle for emancipation from disability. It is therefore a political counterculture which rejects ‘normality’ and societal evaluation of living lives with impairments

Disability pride = the expression of defiance (often as celebration of being who and what we are) against unequal and differential treatment and a demand for social justice, equality and acceptance.

Disability art = production of material that recounts or challenges disabled people’s lived experience of unequal and differential treatment as part of the emancipation struggle.38

NB: Featured image: banner saying Geater Manchester Disability Pride in different coloured letters being carried by a number of people.

Notes

- Disability Pride Month https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disability_Pride_Month

- Bob Williams Findlay (2020) Disability Praxis, Pluto Press, London., Bob Williams Findlay (2025) Coming to terms with disability, Resistance Books. London.

- Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation: Policy Statement’ (Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation, 1974), https://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/library/ UPIAS-UPIAS.pdf

- Disability Challenge 1 (Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation, 1981), 6.

- UPIAS, (1976) ‘Fundamental Principles of Disability’, London: Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation.

- Michael Oliver, The Politics of Disablement (London: Macmillan, 1990), 2. Amelia I. Harris, Judith R. Buckle, Elizabeth Cox and Christopher R.W. Smith, ‘Handicapped and Impaired in Great Britain, Part 1,’ ‘Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, Social Survey Division, Work and Housing of Impaired Persons in Great Britain, Part II’ (London: HMSO

- UPIAS, (1976), 19.,

- Extract from UPIAS circular 3 (c. December 1972) Contribution to the discussion on the nature of our organisation, 3. https://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/library/finkelstein-03-Extraction-from-UPIAS-Circular.pdf

- Chapter 1 (In ‘Cabbage Syndrome’: The social construction of dependence, Colin Barnes (1990) The Falmer Press, 5.

- B. Hughes and K. Patterson, ‘The Social Model of Disability and the Disappearing Body: Towards a Sociology of Impairment’, Disability & Society, June 1997, 6.

- Hughes and Patterson, make this strange assertion: “The problem of mind/body dualism is reproduced by the distinction between disability and impairment. The biological and the cultural are pulled apart. As radical social theory tries to put a closure on the pervasive re-enactment of a rationalist distinction that (everywhere) becomes a denial of the body and desire, radical disability theory proposes a disembodied subject, or more precisely a body devoid of history, affect, meaning and agency.” 6.

- Equality 2025, was a body of publicly-appointed disabled people, that offered strategic, confidential advice to government on issues affecting disabled people.

- M. Oliver, ‘Capitalism, Disability and Ideology: A Materialist Critique of the Normalization’ (Leeds: University of Leeds, 1994), 3.

- Disability activism in 2025, in my view, has no broad unifying framework that would constitute it as a social movement; instead it is reactions to single issues.

- T. Stanton, 2023, Understanding Neurodiversity and Disability: A Comprehensive Guide https://www.neurodiversity.guru/is-neurodiversity-a-disability Stanton presents ‘disability’ under the medicalised definition, while at the same time speaking of making accommodations for people within neurodiverse communities.

- S. Graby (2015) ‘Neurodiversity: Bridging the gap between the disabled people’s movement and the mental health system survivors’ movement?’ In book: Madness, distress and the politics of disablement

- Disability Challenge 1 (Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation, 1981), 5.

- Williams Findlay, Disability Praxis, 127

- Chris Costello, ‘How Capitalism Contributes to Ableism’ (The Mighty, 2017), https://themighty.com/topic/disability/how-capitalism-contributes to-ableism

- Williams Findlay, Disability Praxis, 128.

- Rauscher, L. & McClintock, N. (1997). Ableism curriculum design. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell & P. Griffin, eds. Teaching for diversity and social justice: A sourcebook. New York: Routledge. pp.198–229, 197.

- Fiona Kumari Campbell, Ableism: A Theory of Everything? Keynote for International Conference on ‘Linking Concepts of Critical Ableism and Racism Studies with Research on Conflicts of Participation’, June 6-8 2013, 4. Campbell, F. (2001). ‘Inciting Legal Fictions: ‘Disability’s Date with Ontology and the Ableist Body of the Law”. Griffith Law Review 10: 42 – 62 Taylor, S. (2012). SDS Presentation: Animals and Ableism, Online at http://animalsanddisability.wordpress.com/2012/06/26/sds-presentation-animals and-ableism/ Turner, B.S. (1992). Regulating Bodies: Essays in Medical Sociology. London: Routledge.

- Williams Findlay, Disability Praxis, 101. David Pfeiffer, ‘Disabling Definitions: Is the World Health Organization Normal?’ (New England Journal of Human Services, Vol. 11, 1992); David Pfeiffer, ‘The ICIDH and the Need for its Revision’ (Disability & Society, Vol. 13, No. 4, 1998);David Pfeiffer, ‘The Devils are in the Details: The ICIDH2 and the Disability Movement’ (Disability & Society, Vol. 15, No. 7, 2000).

- World Health Organization, How to use the ICF A Practical Manual for using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Exposure draft for comment, October 2013. 10.

- World Health Organization, 9 – 12.

- World Health Organization, 12.

- Williams Findlay, Disability Praxis, 167. M. Oliver and C. Barnes, ‘Disability Politics and the Disability Movement in Britain: Where did it all go Wrong?’ (2006), http://pf7d7vi 404s1dxh27mla5569.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/files/library/Barnes Coalition-disability-politics-paper.pdf

- J. Morris, ‘Rethinking Disability Policy’ (Viewpoint, 2011), www. .jrf.org. uk/report/rethinking-disability-policy

- Vic Finkelstein, ‘The Social Model of Disability and the Disability Movement’ (Leeds: University of Leeds, 2007), 14, https://disability-studies. leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/library/finkelstein-The-Social Model-of-Disability-and-the-Disability-Movement.pdf

- Definition of disability under the Equality Act 2010 https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/equality/equality-act-2010/protected-characteristics#disability

- M. Oliver, ‘Capitalism, Disability and Ideology: A Materialist Critique of the Normalization’ (Leeds: University of Leeds, 1994), 3.

- Hall, E. (1999). Workspaces: Refiguring the disability-employment debate. In R. Butler, & H. Parr (Eds.), Mind and Body Spaces: Geographies of Illness, Impairment and Disability (1st ed.). Routledge, 143.

- C. Barnes, G. Mercer, and T. Shakespeare, 1999, Exploring disability: a sociological introduction, Polity, Oxford, 14.

- V. Finkelstein, ‘Experience and Consciousness’ (Notes for ‘Psychology of Disability’ Talk), Liverpool Housing Authority, 1990.

- Ibid.

- World Health Organisation, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (Geneva: WHO, 2001), www.who.int/ classifications/icf/en/. United Nations Convention on the Rights of Disabled People (UN acknowledge language self-determination), https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/disability rights/united-nations-convention-rights-persons-disabilities uncrpd.

- Dialogue took place on a Facebook post by Kate Cryer in July 2025. I’m not offering additional details.

- Social Role Valorisation (SRV) is a concept that focuses on enhancing the social roles and valued status of individuals, particularly those with disabilities, within society. It aims to improve their quality of life and promote inclusion and participation. Formulated by Wolf Wolfensberger in 1983, SRV emphasizes the importance of helping devalued individuals find or maintain valued social roles, which is seen as a crucial goal. Overall, SRV serves as a method for improving the lives of people who are of low status in society.

- Bob Williams Findlay (2025) Coming to terms with disability, Resistance Books. London, 89 – 94.