This exhibition is a comprehensive presentation of Rodney’s surviving artworks. He died young at the age of 36 in 1998 as a result of sickle cell anemia which disproportionately affects people of African descent. He spent a lot of time in hospitals, creating work and even curating one of his exhibitions from his bed. His work reflects both a brilliant insight into the Black experience and a reflection on his debilitating illness.

Growing up in West Bromwich he witnessed racism, the violence of the fascists and the progressive fightback of black people and their allies. He was a pivotal figure of the BLK art group of the 1980s. He describes his work in the following way:

‘My work is an insight into the fears, the desires, the realities and anger of the black experience, past, present and future. I create from the standpoint of being black, and for that I cannot and will not apologize’. (page 5 of Whitechapel Gallery pamphlet)

Rather like the Mexican woman artist, Frida Kalho, his art links the painful reality of living with a chronic, life shortening disease with his experience as a black person expressing a consciousness of racism and colonialism. His illness becomes a metaphor for broader social sickness and injustices. The instruments, the mechanics of his medical treatment – transfusions, X rays and his own skin become part of the media of his art.

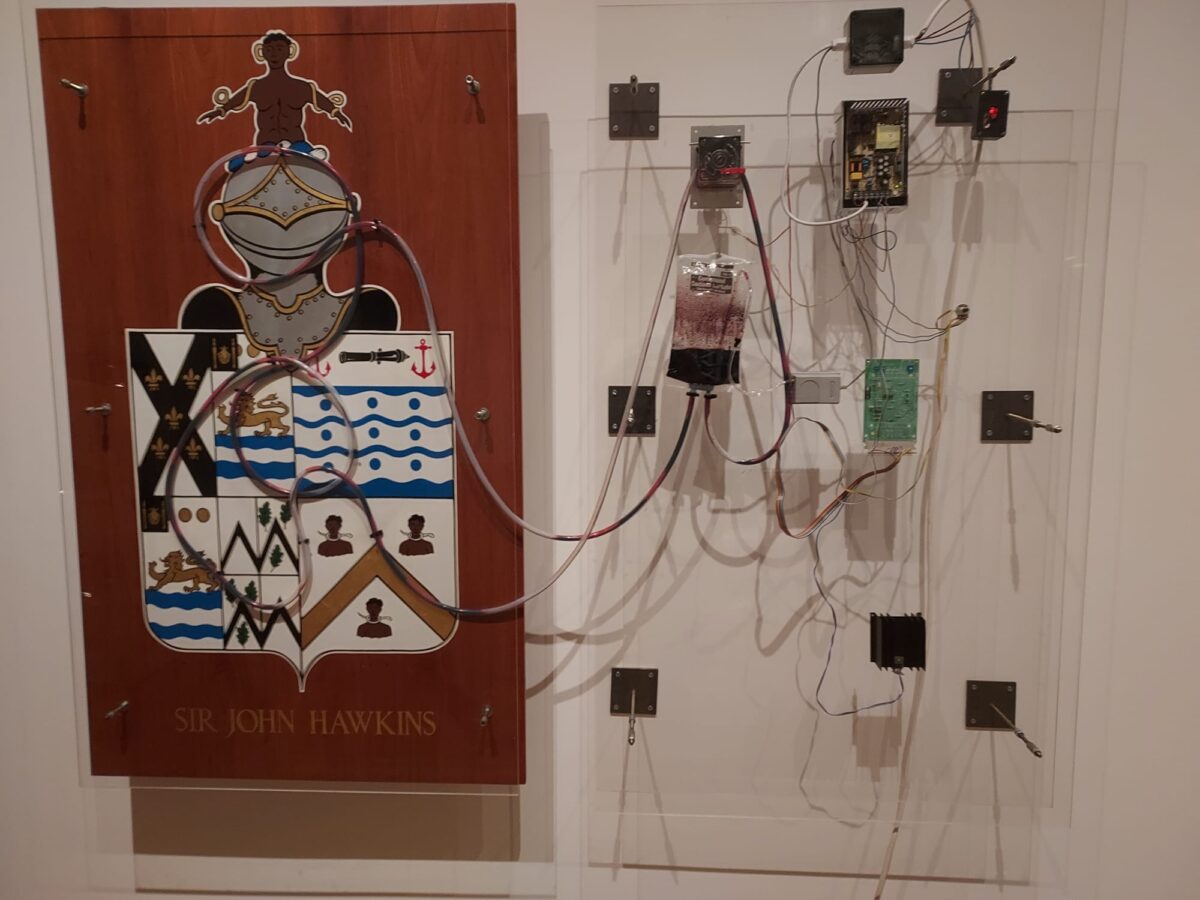

For example, his installation above, entitled Visceral Canker 1990, puts together a commentary on colonialism, slavery and the way sickle cell disease weakens the body. It was commissioned for a site-specific project organised by Television South West. The work was originally installed inside a former military battery in Cornwall which overlooks Plymouth Sound. The two wooden plaques display different heraldic images, linked by a system of medical tubes and electrical pumps that circulate imitation blood. The blood connects the coat of arms of John Hawkins (1532-1595), the first slave trader to sail from Plymouth, to that of Queen Elizabeth 1st (1533-1603).

Rodney wanted to demonstrate his connection as Afro-Caribbean to the enslaved people by using his own blood but Plymouth Council vetoed it. The blood expresses the visceral canker at work in society and how the inhumanity of Britain’s colonial history structures life today. Blood shed by slaves was also the lifeblood that powered British economic growth and wealth. But there is another level of meaning too as Rodney explains:

‘I suffer from sickle cell anemia, a blood conditions almost exclusive to Afro-Caribbean people. Such a condition renders the defence systems of the body inadequate and necessitates a regular change of blood.’

As he further comments this is also a metaphor for the way these sea forts were historically pretty useless as defences.

This work, which heads up the exhibition, is both visually interesting and many layered in its meanings. The artist was truly innovative in both the themes he was dealing with and his use of media. He was also influenced by a Frida Kalho painting called the two Fridas which shows an artery linking two self-portraits of the artist.

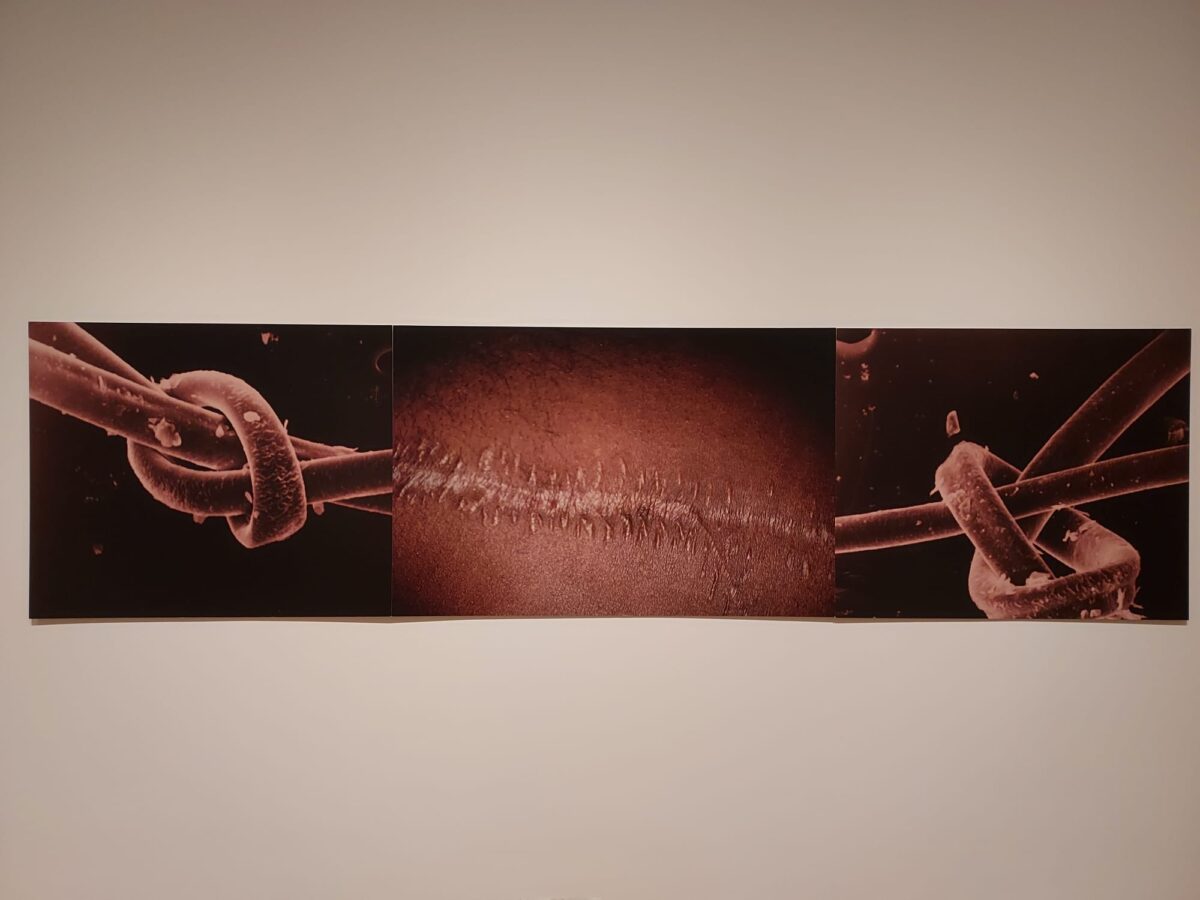

Just like the reluctance of authorities to allow the artist’s own blood to be used in Visceral Canker, when this piece went out to display in hospitals, St Barts in London did not put in on public view because it thought the scar might offend visitors!

Above is Flesh of my Flesh (1996). It shows a thick scar on Rodney’s thigh along with two greatly enlarged human hairs that align on each side of the scar. According to specialists the scar is evidence of medical malpractice since it is very clumsily over done – probably by a surgeon who felt that Black skin was tougher and required more stitches than white skin. The artist has arranged the electron microscope photos of the hair on either side of the scar to show that his hair was indistinguishable from the hair of his fellow artist and friend who was a white woman. So his body becomes the source for a commentary on racism today.

One room of the show is dominated by a shiny display of over 150 trophies representing a variety of sports. They are the sort of trophies schools or amateur clubs give out to their best athletes or the winners of tournaments each year. It is entitled, Doublethink. In place of the usual name and title of the competition won Rodney has replaced them with racist, stereotypical comments about black sports people such as: Black sportsmen have small IQs. Black people are inadequate and bitter. I can remember similar comments in the past about the fragility of Black professional footballers playing in defence when conditions were very wintry which seem incredible today when you look at the number of great black defenders. It was as though their blackness meant they were still only any good in hot conditions when nearly all of these players had grown up in the same climate as their white peers

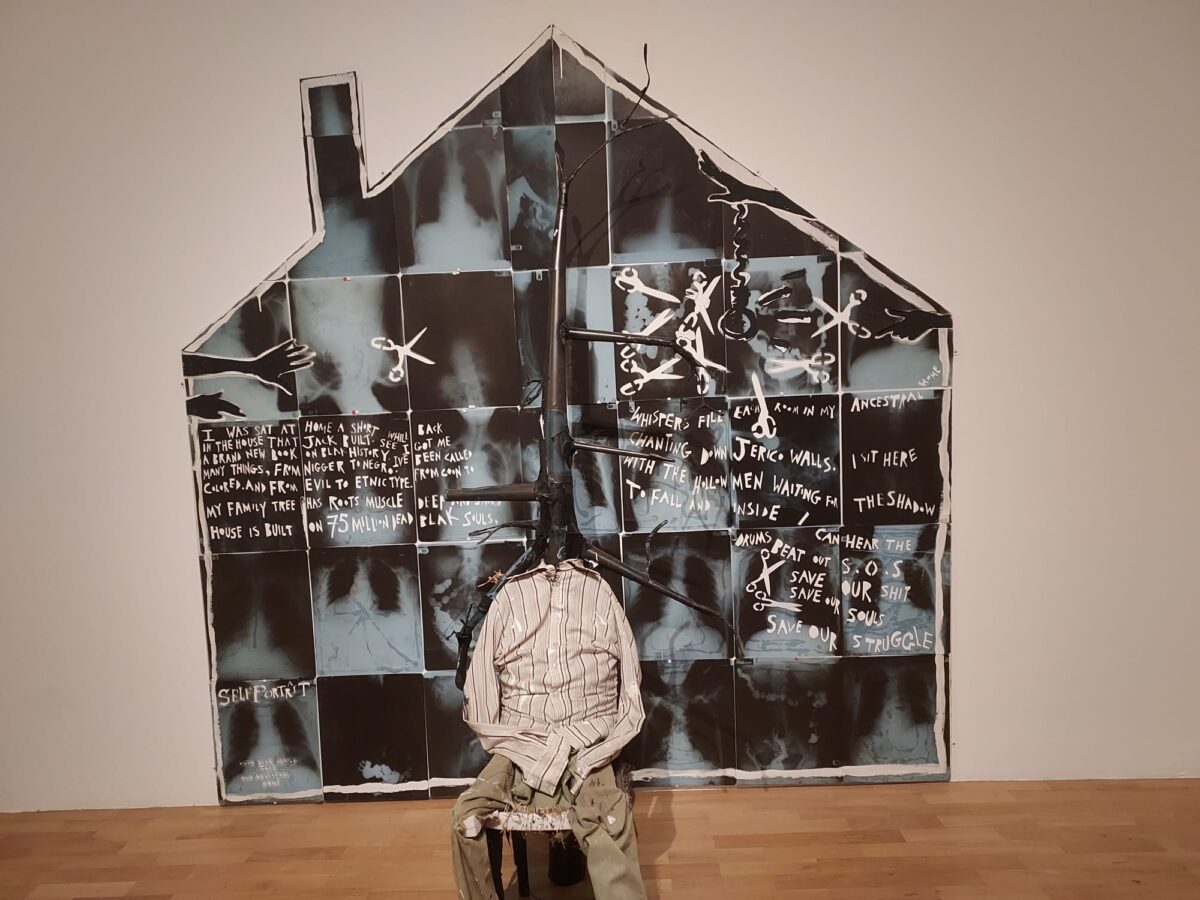

In this installation, The House that Jack Built (1987), Rodney places a sculptural representation of himself with a tree growing out of his head. He sits on a chair with striped shirt and green trousers in front of a picture representation of a house made up of his own X rays. Written on the X ray house are two statements, one identifying the solidity of his roots and identity against racist attempts to ignore or obliterate them and the other celebrating his and his ancestors’ part in the struggle. He often combines text and image in his work. Alongside the text there are white scissors and a noose. Perhaps the scissors represent how his body had been so regularly operated on. A noose is also drawn in black denoting how the struggle was against lynching and that death was always a risk. Of course as the text on the installation indicates this is his identify, his self-portrait. The bare, black tree coming out from his head expresses the rootedness he wishes to communicate. Roots (1977) was the title of a groundbreaking TV series about slavery and the thread linking black people today to Africa.

We can see that Rodney was very tech savvy and he collaborated with other specialists to set up a work called Autoicon. Aware of his limited life span he developed a database of his work so that people could question him after his death. A screen on display shows you how this works. An early form of artistic AI, it was inspired by 19th Century thnker, Jeremy Bentham’s Auto-Icon where he arranged to place his embalmed body in the corridor of University College,London. It is a sort of simulation of an afterlife – a sort of continued artistic production through an interaction between the repository of his work and the public. Somebody interrogating Rodney’s Autoicon is more than just an observer.

Psalms (1997) is another automated creation consisting of an unoccupied wheelchair randomly moving around the exhibition space, apparently autonomously. Rodney was unable to attend the final show due to his illness, so the wheelchair was his idea of indicating both his presence and absence .

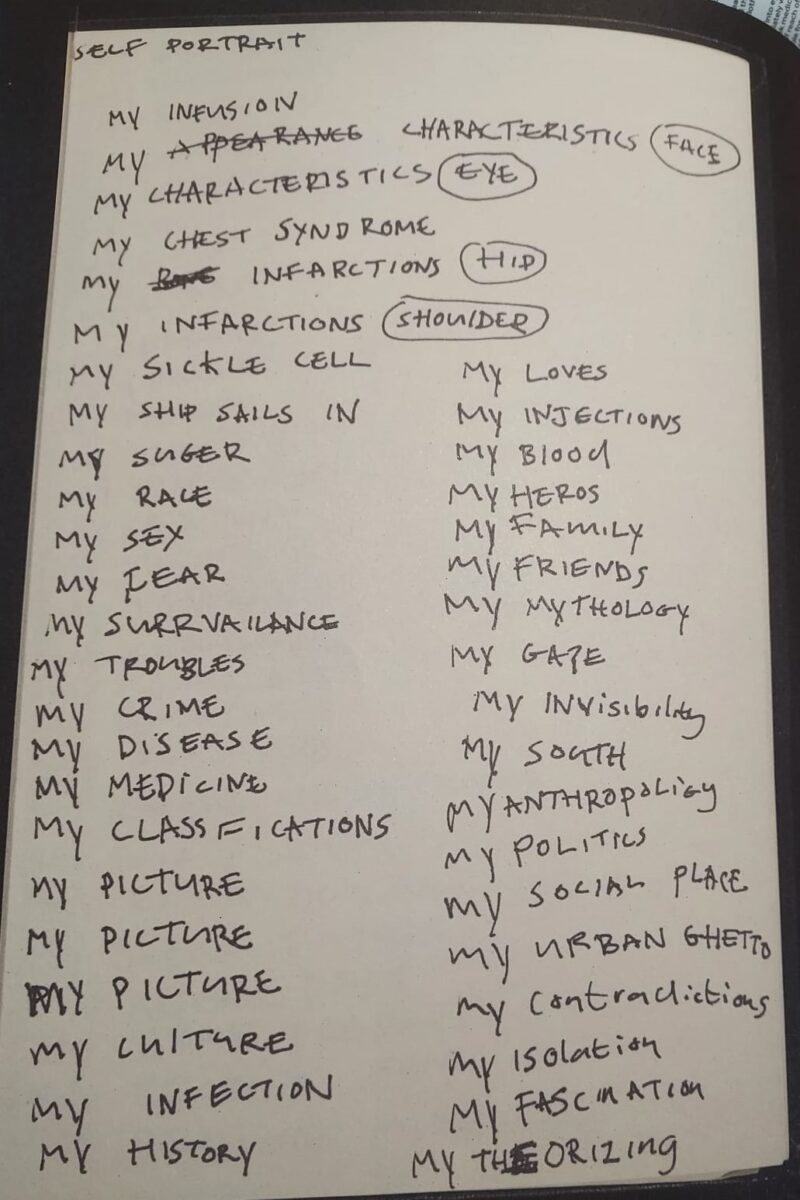

We found the archive section and film show also really worth seeing. The archive gives us a fascinating insight into the artistic process as you can view a selection of his 48 sketchbooks that he saw very much as his mobile studio. You can see above a page from sketchbook 30. A slide show reveals how many of his works did not survive. Many were agitprop type interventions supporting a struggle in specific places.

Certainly if you are in London this show is well worth a visit.

NB The featured image is a photograph of the artist.