Often, when politicians debate a policy concerning social welfare, there lurks behind them a malevolent ghost, a spirit from long ago whose influence is still felt at the highest reaches of government. Quite often, it is the spectre of Thomas Malthus, a cleric and economist writing in the 1790s, most famous for his argument that the poor would breed so recklessly that food production would not be able to keep up and they would impoverish themselves and starve.

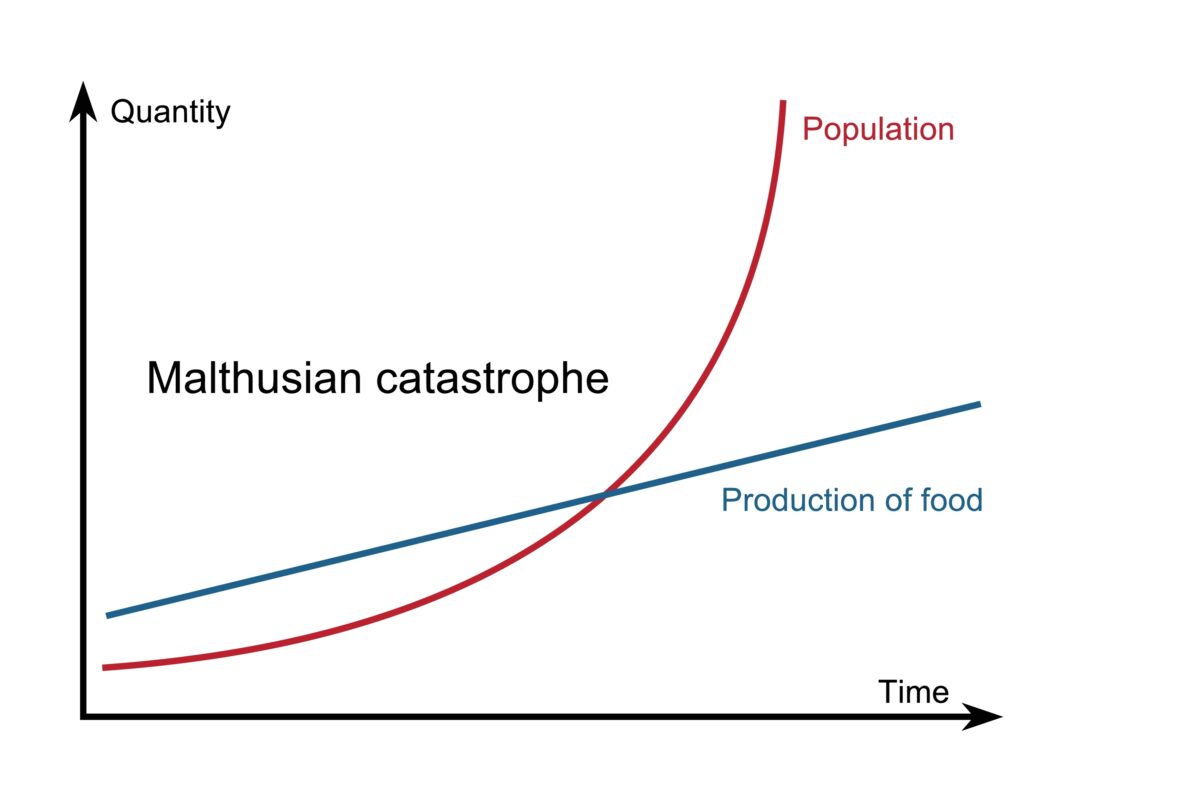

His 1798 book An essay on the principles of population predicted that the national population would double every 25 years whilst food production would lag behind, leading to poverty and misery for the lower orders. Behind the apparent concern for the poor was actually a deeply reactionary view of humanity, informed by false theories and ideas that were almost immediately disproved. His book came out of the historic debates that had been ushered in by the French Revolution of 1789, with pamphlets and books that set out the basis of modern conservative thinking (Edmund Burke), radical liberal thinking (Thomas Paine), feminism (by Mary Wollstonecraft), and philosophical anarchism (William Godwin). Burke’s book came out the same year that the United Irishmen attempted their revolution against British colonial rule and a year after a mutiny in two of the fleets in the Royal Navy, which led to the imposition of harsh anti-working class legislation in parliament, including the suspension of Haebeus Corpus and an extension of the Treason Act. A turbulent time!

Malthus argued that poverty was inevitable; it was a kind of natural law of humanity. In the 1830 version of his book, he outlined his view that “the natural tendency of the labouring classes of society [is] to increase beyond the demand for their labour all the means of adequate support.” The poverty inflicted on the poor left them wretched and miserable, but it was also something they bought on themselves, usually through large families. In response, disease and starvation could provide a positive impulse to the poor because it might force them into work to earn more money to improve their lives (can you see where this is going?)

“Malthus argued that poverty was inevitable; it was a kind of natural law of humanity.”

Despite his fears over excess population, he opposed all efforts towards contraception, including even the withdrawal method, as immoral. He argued that working people and paupers should simply not have sex; abstinence and moral fortitude should be enough. If it wasn’t, then starvation would at least propel people into work.

Of course, Malthus was totally wrong on the question of food. Food production had increased significantly since 1760, and the introduction of new crops like the potato had revolutionised the European diet, but Malthus totally ignored these improvements in his original work. English agriculture became much more advanced during the early years of the industrial revolution as new technology allowed for more efficient farming. Increasingly, any food shortages that occurred were a result not of population growth but of war (Britain’s war with revolutionary France) or capitalists growing food for export instead of feeding people directly (as happened in the Irish famine in 1847).

Today, globally, we have a huge food surplus that could feed everyone, but the capitalist market economy limits who gets what based on how much money you earn or not. Thus, this isn’t a problem of population but a problem of how the market distributes wealth. Capitalists destroy excess food so as not to ‘flood the market’ and drive down prices and, therefore, profit. Malthus rejected any arguments that it was the economic structures that caused these problems, instead claiming it was simply the fate of some humans to be poor: “At the table of Life, not everyone is served”. His view was that if you were born poor and there was no work for you, then you have “no claim of rights to the smallest portion of food and in fact has no business to be where he is.”

We cannot underestimate the importance of Malthus in supporting and advancing the agenda of early capitalism. His chief mission was to absolve those in power of any responsibility for poverty while also opposing any measures that might alleviate their situation because poor people, in their desperation, made better fodder for the factories. As such, Malthus opposed the Poor Laws that existed at the time in England, whereby parishes gave relief to the poorest in their community. He believed that any welfare payments for the poor simply encouraged their continued breeding by ameliorating their suffering. He campaigned for the complete abolition of all measures to provide welfare for the poor, leading to the passing of the Poor Law Reform Act in 1834, which ruined the lives of many and forced thousands into poor houses and forced labour barracks. The rich didn’t want to waste their money on the poor and, in fact, believed that a ‘free’ labour market was beneficial to increasing their wealth as it allowed them to exploit impoverished people desperate to take any job at any wage. This is also why they opposed trade unions, seeing them as an imposition on their right to pay what they wanted for labour.

Malthus argued that there was an increasing number of dependent poor and that this would create an unbearable burden on the taxes of the rich (the economist David Ricardo shared this view). But the increasing numbers of people reliant on Poor Law relief were because of enclosures, which had thrown rural workers off their land and into cities and towns where there often weren’t jobs for them, increasing the numbers of those in need and forming an urban underclass reliant on charity. Malthus blamed their biological urges to breed too much instead of the reality of the brutal social changes happening under capitalism. Likewise, capitalists actually desired child workers and would refuse to hire adults; this encouraged working class families to have children to get an income. High levels of child mortality at the time due to the atrocious conditions in towns and cities only encouraged more attempts to have children. Once again, the poor were blamed for overbreeding when the conditions they lived in encouraged it.

As capitalism developed in Britain, Malthus shifted his arguments from its original position to accommodate some of the changes happening. By 1830, he accepted that the disparity between population size and food and resource production was not entirely natural and that, in fact, the question of property relations and production was not just a ‘natural law’. However, his fundamental point remained: even if you could provide enough food and resources for everyone, that would still be a bad thing to do, as it would only increase the population. He acknowledged that “the means of subsistence” could grow, but it would still fall far short of what was needed to ensure a good life for everyone, unless, of course, you completely reorganised how wealth was distributed, which he opposed as the accumulation of private property and wealth was a natural law (for the ruling class) that could not be violated.

Malthusian ideas influenced reactionary thinkers at the time (and those that came later) to believe that any attempt to accommodate large populations of the poor through wealth or property distribution would lead to a decline in society as mediocrity and lack of initiative would be allowed to thrive. The malevolent ghost of Malthus survived into the Victorian era as the distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor and would go on to be used to justify brutal policies in the colonies in countries like Ireland and India. An ideology that is specifically anti-working class and implicitly racist in its world view, Malthusian ideas can be traced directly to eugenics and the mass slaughter of so-called ‘undesirables’ in the 20th century. It could be seen in the response to the emergence of HIV and AIDs, which disproportionately affected gay men and sub-Saharan Africans—the kind of people that the ruling class were perfectly happy to reduce in number. The ideology lives on today whenever the poor are blamed for their situation so the powerful can escape accountability. We can see how the kind of arguments Malthus was making in the early 1800s are pretty much the script for any editorial of the Sun, Daily Mail, or prominent politicians in Westminster. Recently, we saw it with particular clarity with some political responses to COVID that amounted to just letting it wipe out the elderly and the medically vulnerable.

“Malthusian ideas influenced reactionary thinkers at the time (and those that came later) to believe that any attempt to accommodate large populations of the poor through wealth or property distribution would lead to a decline in society.”

Elsewhere, Malthusian ideas have been re-appropriated as the basis of greenwashing reactionary environmental politics, which claims overpopulation is the central crisis in the world today and not the capitalist system that structures and determines our relationships to each other and to the planet. It can also be seen in the debates about welfare policy in the West, including the two-child benefit cap in Britain, an austerity policy specifically designed to encourage people with larger families to go out to work. It also goes to the heart of the debate over personal or social responsibility: are people poor because of their own lazy, feckless irresponsibility, or do we look to the economic structures of capitalism to understand our society?

This is not to say that Malthus is the only reactionary thinker of the capitalist era, but he set the agenda and popularised ideas that others took up and developed. His ideas were the bedrock for how the ruling class has come to see the poor as a sea of mouths to feed, brought on by their own irresponsible nature to breed beyond what the capitalists can find a use for in terms of people to exploit. The world has been shaped by Malthusian ideas, and it is time to put all of them in the bin and consider a world based on human need and not a defence of the privileges and entitlements of the wealthy whilst the victims of their system struggle.

In opposition to Malthusian ideology, socialists look at the society we all live in. The problem isn’t overbreeding by the poor; our planet has more than enough resources for all of us. If there is a concern about the size of the human population, then the primary factor in reducing family size is the level of women’s education; this is something that can be improved through a general increase in the public wealth of any society. In fact, Malthus’s fundamental point that more money means more children and more poverty has generally been proven wrong; richer nations in the modern age have declining populations.

Even if some people in our society are ‘lazy’ (as in unmotivated) in terms of work, we have to look at the wider issues: the quality of jobs, the level of wages, and how engaged people feel around improving their lives (also, how lazy are shareholders or landlords who just live a parasitical relationship to property and wealth?). Socialists challenge this view that such a thing as the underserving poor exists, or if they did, they deserve poverty and misery to encourage them into work; that way leads to the workhouse and eugenics. These politics are rooted in capital as a form of scarcity: the working class must fight for the crumbs while the rich swan around on yachts or private jets.

We can create a world that meets everyone’s needs as long as we escape the capitalist paradigm, which privileges power and wealth in the hands of the few while demonising and blaming the poor for their own situation.

“We can create a world that meets everyone’s needs as long as we escape the capitalist paradigm, which privileges power and wealth in the hands of the few while demonising and blaming the poor for their own situation.”

Art (52) Book Review (121) Books (114) Capitalism (65) China (79) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) Economics (39) EcoSocialism (55) Elections (82) Europe (44) Fascism (56) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (69) Gaza (59) Imperialism (97) Israel (119) Italy (45) Keir Starmer (52) Labour Party (110) Long Read (42) Marxism (47) Palestine (163) pandemic (78) Protest (149) Russia (334) Solidarity (133) Statement (48) Trade Unionism (134) Ukraine (339) United States of America (130) War (362)

Latest Articles

- Turkey and the Neofascist ContagionThe ongoing battle in Turkey has become increasingly significant for the entire world. If the Turkish popular movement wins, its victory will have a significant impact in galvanizing resistance to the rise of neofascism worldwide argues Gilbert Achcar

- The boys are not alrightSimon Pearson points out that a Minister for Men cannot rebuild the infrastructures of solidarity that were torn apart by decades of neoliberal consensus.

- Yemen on the brinkNow that Trump has returned to the White House with far greater arrogance than during his first term, the possibility of re-escalating the war in Yemen with direct US involvement has become very real, argues Gilbert Achcar

- Labour austerity – balancing the books on the backs of the poorestDave Kellaway on Labour attacks on disabled people

- Turkey: a mass movement builds against Erdogan’s power grabUraz Aydin answers questions from Antoine Larrache about the mobilization currently building in Turkey after the arrest of the mayor of Istanbul, who is seen as Erdogan’s main rival in the race for the next presidential election.