Photography came to Africa as part of the colonial enterprise. It helped construct the social documents of racial surveillance. Photographs were used by anthropologists or other researchers to develop ethnographic archives some of which reinforced pseudo-scientific ideologies of racial hierarchies. Images of naked or semi-naked African women were also included in magazines, reviews or books in the imperialist centres for the prurient male gaze. Commercial studios were established, mostly in the urban centres by settlers, but later African photographers did the same. To some extent getting a portrait done in a studio in the classic Victorian or early 20th Century style represented a certain integration into white, western culture. Subsequently African photographers became to subvert this with their own adaptations of the posed portrait.

This exhibition of thirty-six photographers challenges a history of photography in which African subjects are framed predominantly by a Western lens. A new generation of artists interrogate the camera as an imperial ideological weapon. Photography, video and installations are on show. Different ways of telling the African story chart the pre-colonial heritage, migration and globalisation. Over simplified Western versions of African history and culture which conflates its diversity into a single entity are rejected. The exhibition recognises the way Africa is part of global history but with unique forms of knowledge, myth, ritual and experience. Colonialism violently disrupted this culture but the World in Common exhibition shows how new forms of image-making can produce alternative visions of the future. We see how the power of photography can reimagine history.

The Tate family’s helped sponsor this art gallery, their sugar companies date back to the slave trade and sugar plantations in the Caribbean. It is only historically just that today the gallery is making some efforts to broaden the representation of artists from previously unrepresented regions of the world.

One of the theoretical inspirations behind the exhibition is the writings of Achille Mbembe.

Acknowledging the denial of humanity associated with the colonial encounter and its afterlives, Mbembe posits the notion of ‘a world in common’ in which Africa’s histories are understood as part of a global narrative of civilisation. (…) Mbembe argues for the rethinking of African experience in relation to global networks and cosmopolitan identities (…) this universal humanity offers a path towards a new ways of inhabiting the world

From exhibition catalogue pp 9-10

Here are some of my highlights:

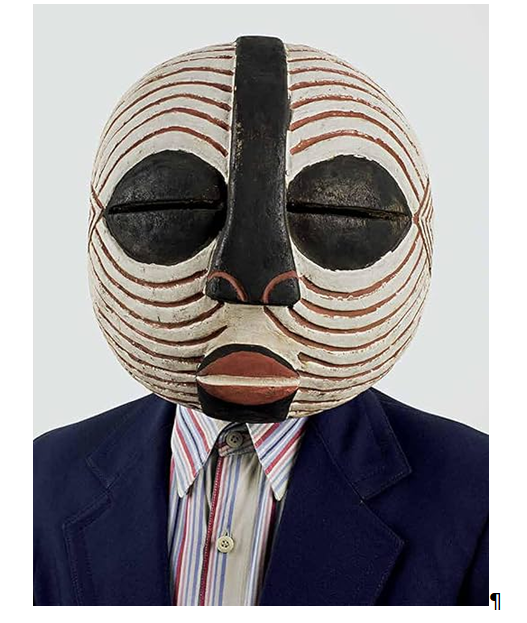

Chagas put traditional masks on sitters wearing modern clothing. He is asking how far are these masks universal markers of authenticity and identity? Remember Picasso and other modernists at the beginning of the twentieth century ‘discovered’ and appropriated such masques and incorporated them into the Cubist movement. The recent Picasso documentary on the BBC stated that Picasso never really accepted his debt to African culture at the time. In his series of photos Chagas is commenting on how these masks are sought after objects in the art world. They circulate freely throughout the West but the movements of African citizens are tightly restricted and thousands perish (like their ancestors in the slave passage) in migrant boats in the Mediterranean today.

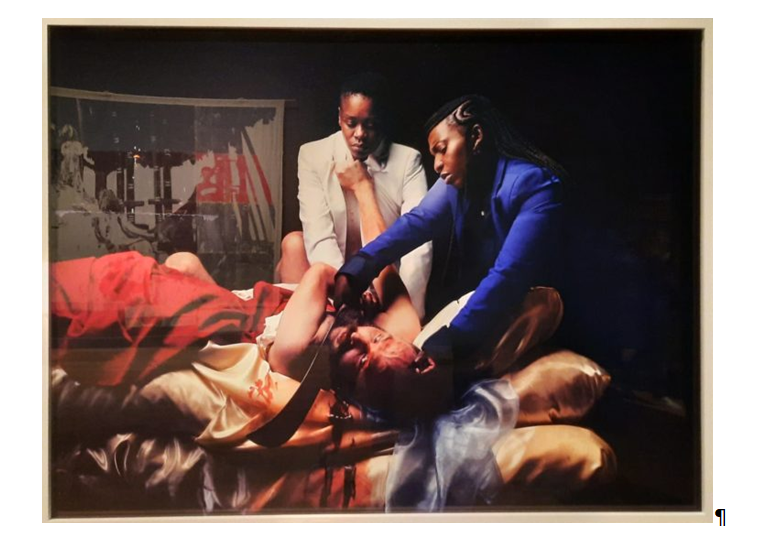

In this image there is a very direct reference to the canon of Western Art, to Artemisia Gentileschi’s painting, Judith slaying Holofernes (1613). Here a Black woman is slaying a white man. It seems to symbolise a desire for retribution and justice against sexism and racism which are both part of colonialism. Gentileschi painted her picture as a response to her rape by another artist. So here ‘Black women replay and subvert iconic European classical paintings’ (catalogue p 23).

In African today millions of people still do not have access to clean water and often walk miles every day to fill plastic buckets. Here this reality is transferred to an urban setting with masked women. This was also a performance piece enacted in the streets of Lagos, Nigeria. The artist and six other performers in matching jumpsuits carry kegs of water strapped to their ankles catching the attention of passers-by as they leave trails of water behind them. The costumes relate to traditional Egungun masquerades which women are not allowed to perform so the performance ‘draws from this tradition by allowing women to occupy a sacred and dynamic space within the public environment’(Ogunji) She continues to pose the question, When do people have an opportunity to rest, reflect , envision, imagine and enact another way of being..

I found these photos both beautiful and very original. The photos were made as he made a year-long journey from Africa to Western Europe, passing through Mali, Mauritania and Sicily. The subjects hold horizontal mirrors to the landscape revealing glimpses of coastlines, train tracks and power lines. These are places that the camera cannot access so you feel a disruption, a displacement in the landscape. He chose locations which were often border crossings.

Petro’s images connect distant geographies, revealing how the legacies of colonialism shape present narratives of migration as a global reality.

(catalogue p213)

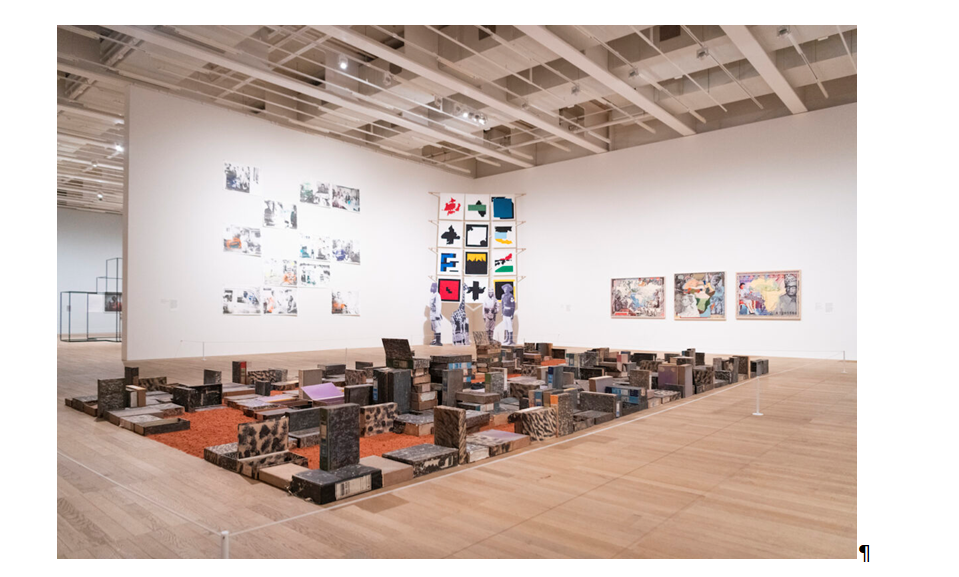

One room of the exhibition has half its floor covered with the actual documents crucial to colonial expansion – official photographs, images, maps and classifications. You could call it an imperial archive. The artist exposes the hidden narratives of the archive to create an image of contemporary society ‘haunted by the ghosts of the past’. Stuart Hall, a very perceptive Marxist writer, commented the ‘living archive opens history to the possibility of imagining the past to produce alternative visions of the future’ (catalogue, p150).

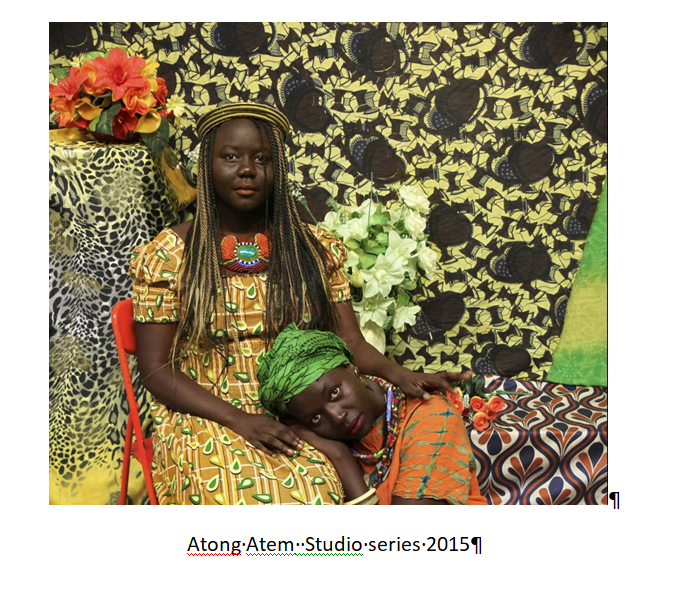

These stunning photos erupt from the gallery walls with their rich, intricate colours and with proud African people. The artist wanted to challenge colonial ethnographic depictions that presented the subjects in a skewed and problematic way.

I wanted to see what happens when we turn the lens on ourselves and subvert the ethnographic gaze. To me, it’s a moment of power and reclamation, and an opportunity for us to celebrate ouir personal and cultural identities.

Atem, (catalogue p 140)

In this review I have picked out just a few of the images that I particularly liked. There is a lot more than this to discover in the exhibition. Such a show opens a door into a world that is not particularly represented in Western media. It is a well worth trying to catch it before it closes in January. If you live outside London you could fit in a visit before or after the national Palestine demos.

Art (52) Book Review (121) Books (114) Capitalism (65) China (79) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) Economics (39) EcoSocialism (55) Elections (82) Europe (44) Fascism (56) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (69) Gaza (59) Imperialism (97) Israel (119) Italy (45) Keir Starmer (52) Labour Party (110) Long Read (42) Marxism (47) Palestine (163) pandemic (78) Protest (149) Russia (334) Solidarity (133) Statement (48) Trade Unionism (134) Ukraine (339) United States of America (130) War (362)