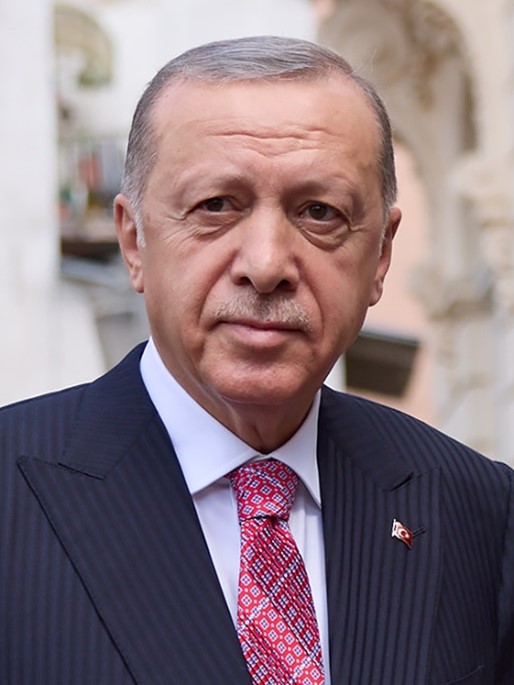

Dave Kellaway: Why does Erdogan keep winning? There have been problems with the economy; the earthquake exposed corruption both in the construction quality of houses and in the aid distribution; and the restrictions on freedom of expression must surely be fueling opposition to the regime.

Uraz Aydin: Erdogan has been able to build his power base by exploiting the intense polarisation in Turkish society. On the one hand, we have a cultural and religious polarisation, and on the other, a social and class polarisation. After the foundation of the republic (Kemal Ataturk, 1923), which had a strong secular aspect, religious people were excluded from positions of power for a long time. Even though the conservative religious political currents survived, the dominant ideology in society was secular and urban, and it excluded those forces. Outside the towns, in rural society, and among the poorer layers, the story is different. That is why, whenever there were elections, the conservative and religious parties had a base among the peasantry and in rural areas. In the towns, you had the intellectuals, the working class, and the urban petty bourgeois and bourgeois classes.

These conservative religious parties were always there, challenging the Kemalist Republican Party. That is also why there were military coups d’états so that this republican, bourgeois, military elite could maintain its power. However, in 1994, in the local elections, including in Istanbul, Erdogan’s Islamist party emerged very strongly. Its profile was not just religious but also had a social programme. The Islamist parties, even where they won votes and could get into government, were repressed by the military.

At a certain point, just after 2000, Erdogan understood that another sort of party was needed that would avoid immediately provoking the military to take action against it. He put forward proposals for Turkey to become a member of the European Union, and he entered into dialogue with other political parties. Neo-liberalism was embraced, and it tried to project itself as a modern Islamist party. So in 2002, he won power after the centre parties had failed to deal with the economic crisis. He has been in power ever since—22 years.

His first ten years were less authoritarian, and he tried to avoid any confrontation with the military. Remember, this was also a period of economic growth internationally that ended in the 2008 crash. The crash came later in Turkey. There was a lot of money around that the bourgeoisie was happy with, and he was able to take certain measures to help working people and the poor. However, Erdogan did not establish a real welfare state or social security system; it was more a system of handouts. After 2010, he had more difficulties with the military. So Erdogan constructed an electoral base on one side of the historic polarisation among the religious-minded, the poor, and especially in rural areas. His party won many local councils, and he used that as a transmission belt to hand out money and resources like charcoal to the deprived layers of society. Also, the party could use the distribution of local authority jobs to cement its support; people voting would know their jobs, and handouts relied on re-electing Erdogan’s party. Non-government organisations that were fronts for the government were also set up to distribute support.

Twenty years of this regime have meant other changes. Islam is no longer excluded from public institutions; before, it was forbidden for women students to wear scarves (hijabs), but now they are allowed and encouraged. Today there is increased poverty and deprivation, but that in itself does not mean the masses will switch allegiance away from Erdogan.

So religious ideology can cancel out or balance out other concerns. We thought, with the earthquake and the opinion polls, that Erdogan was in trouble last year with the elections. But it did not turn out as predicted.

We all thought the same. When we were arrested after protests after the earthquake, we were even told by the police agents that they thought Erdogan was gone. Erdogan has become much more nationalist and far-right. Previously, he had started an exchange with the Kurds about dealing with their demands. That process did not work, and he turned to ultra-nationalism. He made an alliance with the “traditional” fascist party of Turkey, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP).

Is there a possibility that in the coming elections an even more extreme right-wing current could replace Erdogan?

This is a possible trend. Erdogan’s party is more of a movement than a party. There is no real internal debate; it is the court of Erdogan. Of course, there are a lot of arrivistes or careerists who have flocked to the party of power. They have to submit to Erdogan’s will if they want to get on. It is a bit like the Stalinist system. The most sycophantic rises the highest. Corruption is key too; with Erdogan, you have the green light for all sorts of speculation in property or other business. In return, Erdogan gets a contribution from your profits. He has built up a section of the bourgeoisie that is dependent on him. There are no longer really any rules or regulations. Every decision is based on the current interests of Erdogan. This applies to foreign policy too. He flirts with Putin, but he can speak in favour of NATO too. Erdogan puts himself forward as an intermediary between Ukraine and Russia. The transition to multipolar imperialism and the relative decline of the USA in the Middle East increased the capacity of medium-sized powers such as Turkey to act more autonomously. Erdoğan is using this new advantageous international situation to the fullest and is pursuing a more aggressive foreign policy.

The bourgeois opposition to Erdogan is very divided. Is there a possibility of a military coup down the road if there is a stalemate or vacuum of bourgeois leadership?

Nothing is certain, but the military too has subordinated itself to Erdogan. We did have an attempted coup in 2016 orchestrated by another Islamist group that was one of his former allies. This group had worked at infiltrating itself into some positions within the state. It was a real coup—not something manipulated all along by Erdogan. But it is possible that he allowed it to develop a bit without intervening in order to gain more out of its failure.

Could we talk a bit about your party, the Turkish Workers Party (TIP), because even with the success of Erdogan in the 2023 election, you managed to win 1.7% of the vote and hold on to 4 MPs? If you looked at these results in the context of the performance of other radical left parties in Europe—for example, there are no longer any left MPs in the Italian parliament—this is not so bad for a party that calls itself Marxist.

One of the MPs on our list, Can Atalay, is still in prison. We already had four MPs in the previous parliament, and we had worked in coalition with the Kurdish parties, which have a significant electoral and social base. The TIP has a very combative approach, unlike the official left-of-centre opposition, and has attracted support from people who want to fight against Erdogan’s AKP party. The party has grown very fast; when I joined two years ago, it had 6,000 members; today, it has 43,000; in January 2023, we had 10,000, so we quadrupled our membership in a few months. There were three steps.

First, one of our MPs made a YouTube video where he was asked various questions by a hostile audience about the right, the left, and the Kurds about Marxism, and he responded very effectively, which helped us win thousands of new members. We could hardly handle all this rush of applications to join.

Second, we had the earthquake, and our comrades responded very quickly. The whole organisation turned to the task of mobilising citizens to support the people suffering in that region. TİP was able to mobilise a very effective mutual aid and solidarity organisation in the face of the earthquake disaster. Hundreds of trucks were organised. People saw they could trust us as we helped organise vital supplies for the area. We were not seen as corrupt. Even some bourgeois organisations sent stuff through us. Third, the mobilisation around our election campaign drew even more people around us. However, with the victory of Erdogan, there was a general demoralisation of the whole opposition, and it has affected us too. We may still have 40,000, but realistically, we have ten thousand or so activists at the moment. People have not necessarily left the party, but they have become inactive and could be remobilized. What was interesting about our vote was that we did not only win votes where we expected them among the urban, secular, and educated parts of the population, but we also began to win votes where the AKP is strong. We are talking about a few percent, but this is something new for us. We are beginning to cut through with a line focused on working class interests rather than making a dividing line on a religious or cultural basis. The presidential elections were held at the same time as the parliamentary ones, and we saw people splitting their votes between ourselves in the parliamentary elections and Erdogan for the president. So these people still saw Erdogan as the great father figure, the “Reis,” but saw that we could be useful in defending their interests. This is new. On the left, we have to overcome the rigidity of the polarisation between secular, nationalist, and religious identities. The current political polarisation in Turkey is not class-based. As I mentioned before, it is a polarisation that has developed mainly on a cultural basis. TİP aims to transform this polarisation into a new and essentially class-based political polarisation.

Does the TIP see itself like the left populist currents such as Podemos or Syriza building mass left parties?

Not exactly since TIP came out of a split inside the Turkish Communist Party, which was rather Stalinist and nationalist. The split was in part over the attitude towards the Kurdish question. The people who split are also more open about feminism and LBGT+ issues. Its guiding ideology is Marxist. Its publication is called Communist. But it was involved in the uprising around Gezi Park in 2013, when people stopped speculators from taking over this public green space despite brutal state repression. The new party was impregnated by the diverse strands of people involved in this campaign, particularly the youth.

Today, however, it is difficult to organise youth; it is very repressive in secondary schools, and university students cannot organise unions; they live at home because rents are so high and they usually have to work to finance their studies. Student life as we knew it does not exist so much now. So it is rather people in their 30s that we are attracting.

Do you have an Iglesias (Podemos) type problem in the party where the main leader(s) with a big media profile can dominate and bypass the internal democracy of the party?

It is not really the same. Our MPs are very well known because of their radical interventions in parliament, and of course the leader (the “president”) of TIP, Erkan Baş, is an important political figure. But we cannot say there is a domination of the leader; it is more a collective political leadership. We should not forget that, unlike Podemos, TIP comes from a revolutionary tradition, the Bolshevik tradition. So the structure of the party is based on committees (central, regional, local, etc.). By the way, internal democracy, even in the Leninist-Trotskyst tradition, was far from perfect. Internal democracy is a mechanism that you have to conquer, with internal debate, of course, but also with concrete experiences.

I think it is important to build this party, as it is currently the best instrument to carry forward the struggle for a socialist alternative in Turkey. Inside the party, people know I come from a different political tradition to them, but I have been able to take on some leadership roles; for example, I am the secretary of the party in an important area of Istanbul, and there are a range of views on the central committee.

One positive approach adopted by the TIP is not to only try and win new members and support from the secular, non-religious sectors, the educated youth, and intellectuals but also to reach out to the base of the more religiously oriented working class and poor through work around working class demands.

These divisions between different sectors of the working class—between graduates and non-graduates, between the big cities and the smaller towns or more rural areas—also exist in European countries. In Britain, we saw this with Brexit, and in France, with the Yellow Vests movement. So how you overcome this division is very important strategically.

Yes, I agree. Even in Istanbul, there are big differences between some of the suburban areas that are very working class but more conservative and religious and the more central areas, where there are bigger numbers of young people, intellectuals, and progressives.

What about Palestine solidarity here? We saw the brilliant multi-media exhibition in Taksim Square with digitalized art work from Palestinian children that is financed by the government.

Here, we had eighty or so resignations from the party in my branch when we supported the right to resist the Israeli occupation. For activists who have been battling against AKP Islamism, they see Hamas as a similar problem. We did not identify with Hamas’s political line, of course, but it was controversial for us. Of course, this is the first time that the Erdogan government has supported mass demonstrations. We can take advantage of this to organise our solidarity demonstrations or contingents.

Although Erdogan’s government claims that it is on the side of the Palestinian people, this is not the reality. While Israel’s colonial aggression continues at full speed, Turkey’s commercial relations with Israel continue to develop. Apart from some verbal statements, the Turkish government has not shown any concrete solidarity towards the Palestinian people. This situation causes objections among Erdoğan’s base. I believe that socialists should listen to these objections and take the leadership of the solidarity movement with the Palestinian people. The left here can win votes, but it is difficult to mobilise many thousands on the streets; the repression over the years has made this difficult. Just to give an example, eighty of our activists (and I’m one of them) were on trial the other week because they protested about the corruption connected to the distribution of tents in the earthquake area. The Red Crescent had been selling tents to non-government organisations. The police had attacked our protest, which is the norm these days.

Can you tell us a little about Can Atalay (for more details about him and his campaign, click on his name), the MP who has still not been released from prison?

I have known Can for many years. He is a lawyer and was one of the spokespeople for the Gezi Park campaign. He also defended people over labour laws and safety issues. He was condemned to 18 years in prison for his role in the Gezi Park campaign. We put him on the TIP electoral slate as an independent. Once elected, the state has taken action to remove his parliamentary immunity. Different courts at different levels have given different verdicts. The constitutional court said he must be released, but a lower court then said the opposite. But he remains in prison. We are calling it a constitutional coup because the lower court contradicted the higher court. So now we can talk about a state crisis around the legitimacy of the constitution.

Amnesty International information and campaign for Can Atalay are here.

Art (54) Book Review (126) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (45) EcoSocialism (58) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (61) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (72) Gaza (62) Imperialism (100) Israel (129) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (56) Labour Party (114) Long Read (42) Marxism (50) Marxist Theory (48) Palestine (177) pandemic (78) Protest (154) Russia (341) Solidarity (146) Statement (49) Trade Unionism (142) Ukraine (349) United States of America (134) War (368)