Many people have probably seen one or other of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) pictures, even if they do not know much of the background of the first self-proclaimed artists’ movement to develop in this country. The Lady of Shallott (Waterhouse) or Orphelia (Millais) are some of the most famous and popular images in British art. There have been regular blockbuster shows of their work over the last thirty years, and given that the new Victorian industrial capitalists were often buyers or patrons of these artists, you can see many of their works in Manchester, Liverpool, or other towns outside London.

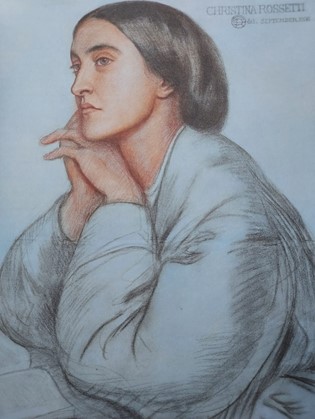

However, this show is interesting in that it re-establishes the importance of the political refugee family, the Rossettis, in leading the movement and also the important role of women, particularly Christina Rossetti, the poet, and Elisabeth Siddall, who was briefly Dante Rossetti’s wife but had been his model and then became an independent artist.

This show puts the sisters back alongside the brotherhood. Elisabeth Siddal‘s life and work have often been seen through the prism of her husband, first as a muse and then as a quasi-pupil. Much ink has been spilled on the stormy relationship and her tragic early death through a laudanum overdose.

As you enter the exhibition, well-known poems by Christiana Rossetti are projected on the walls, and you can stand in a number of spots to listen to them. Indeed, at her death, she was better known and had made more money from her poetry than her brother had from his art.

The Rossettis were an Italian nationalist family that had fled Italy as political refugees. The father taught Italian literature in London and was a Dante specialist. There were two sons, Dante Gabriel and William, and two daughters, Christina and Maria. Their parents encouraged their intellectual, political, and artistic growth. A relative in London was a publisher, and from an early age, they ‘made’ art, mostly pictures and poetry. Political radicals from England and Europe would pass through their home.

It was a fertile environment for Christina to explore her own femininity, emotions, and faith. The family would collaborate on artistic production, so Gabriel would illustrate Christina’s poetry collections. Later, William would publish people like Walt Whitman, and in many ways, he was the most political of all of them, working with William Morris. Maria, like her sister, Christina, committed herself to helping women sex workers through an Anglican women’s order.

Christina’s poetry lives on today. Her In the Bleak Midwinter is regularly sung at Christmas carol services. Her poem, Remember me when I am gone away, is often used in funeral services. Its last two lines are well known:

Better by far you should forget and smile Than that you should remember and be sad.

TV viewers might have noticed lines from her in Peaky Blinders, Boardwalk Empire, The Crown, Downtown Abbey, and Ghosts. Love is the theme she returns to: familial, ecological, romantic, creative, and spiritual. But she rejected Victorian sentimentality; love was painful but also transformative. Her poem, In an Artist’s Studio, which most people say is about her brother’s tempestuous relationship with Elisabeth Siddal, does reflect a woman’s understanding of the unequal relationship between the male artist and his muse or model:

He feeds upon her face by day and night, And she with true kind eyes looks back on him Fair as the moon and joyful as the light: Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim; Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright; Nat as she is, but as she fills his dream.

She refused to join the Brotherhood despite being invited; she had a strong sense of Christian propriety. Indeed, as Dinah Roe (page 48) points out in the catalogue, this poem is not just about the power relationship between the painter and his muse but also about the impossibility of the artist painting reality since, for Anglo-Catholics at that time, the world was not real but simply an illusion, a mirror reflecting the real world of heaven. Her brother, William, criticised this belief as ignoring social reality. Looking at the world as a mirror allowed Christina to freely criticise its conventions. At the same time, she was an animal rights activist, helped disadvantaged women, and chose to be buried in a bio-disposable coffin. This exhibition opens up a whole new look at Christina Rossetti, whose poems we used to read at secondary school in the early 1960s!

Elisabeth Siddall worked in a hat shop when she was discovered’ by the PRB and became its star model, notably as Orphelia in Millais’s painting. The PRB did seek out ordinary women, including sex workers, for their models. To a limited degree, this did challenge at least the art world’s relationship to class. Remember that portraiture at the time mainly consisted of the rich landowners and aristocracy being painted by Reynolds and Gainsborough? The pictures were records and emblems of their status; sometimes they were pictured in front of their property. The PRB found new patrons—sometimes the new money of the rising industrial bourgeoisie—who were happy with portraits from classical or literary sources. It was still the dominant male gaze, so erotic, ‘gorgeous’ women were still a hot sell, which Dante Gabriel could paint brilliantly. Here, you can see the largest number of his paintings ever displayed in one place.

Siddal was adamant about wanting to become an artist, and you had to be pretty determined as a woman to do so in the Victorian era. Her work as a model had already given her some background. This exhibition is the first to have collected so much of her work. More importantly, it shows the two-way relationship with Dante Gabriel. Historically, her work has been seen as very much secondary or derivative of his. You can see in the sketches that she influenced his work. In a specialist article in the catalogue by Glenda Younde (page 114), you can see how he incorporated compositional ideas from her.

The way the arms are drawn in Siddall’s painting of the Eve of Saint Agnes is replicated in Dante Gabriel’s illustration for Christina’s poetry volume. To his credit, he acknowledged her contribution and made photographs of a number of her sketches. He kept this portfolio in his studio. She was independent to the end, visiting the South of France for artistic inspiration on her own.

The exhibition finishes with what has come to be known as Rossetti’s stunners—his pictures, Lady Lilith, La Ghirlandata, Proserpine, and so on. One feature of these portraits is the abundance of red or golden hair. In the Victorian period, according to Sarah Heaton (in Cultural History of Hair in the Age of Empire), hair was ‘a site of contested discourses’ and ‘patriarchal control’. Adult women were expected to be kept prim and proper and restrained. As time went by and women took on more public roles in the second half of the 19th century, these restrictions loosened somewhat. Indeed, the character of Lilith, the female equal of Adam in the Talmudic story, was, according to Gabriel:

‘the first strong-minded woman and the original advocate of women’s rights’.

He painted the subject several times, and his engagement, according to Virginia Allen (page 192 of the catalogue), is an expression of:

‘not only what men saw in the feminist movement in the broad sense but what was understood to be the major hazard of that movement, the escape of women from male control of their sexuality’.

So there remains ambiguity about Rossetti’s work.

This show also tells us how the Rossettis encouraged a sort of multimedia art before its time, with pictures illustrating literature or drama with poetry written on the frames. Books were created with poetry and original artwork. Later, they linked up with William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement. One room shows the furniture on which Dante Gabriel collaborated.

Reviews of the exhibition have been mixed—certainly not many 5-star verdicts. On the one hand, the Telegraph slammed it for its so-called political correctness and its emphasis on the women in the movement. On the other hand, Jonathon Jones, ever the iconoclast, used his review to lambast the limitations of Dante Gabriel. Overall, I think neither reaction is fair to the curators’ attempt to provide another narrative of the PRB through the agency of the Rossetti family and particularly the women.

Art (53) Book Review (121) Books (114) Capitalism (65) China (79) Climate Emergency (98) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) Economics (40) EcoSocialism (55) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (56) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (69) Gaza (59) Imperialism (98) Israel (119) Italy (45) Keir Starmer (52) Labour Party (110) Long Read (42) Marxism (48) Palestine (164) pandemic (78) Protest (151) Russia (340) Solidarity (141) Statement (48) Trade Unionism (139) Ukraine (345) United States of America (132) War (368)

Latest Articles

- Against Bad Arguments for Terrible ThingsA Reply to John Rees from Holly Lewis

- Bob Cullen 1949 — 2025Tony Richardson, who worked for 34 years in the Body Plant at the key British Leyland factory in Cowley, Oxford and was a shop steward for most of that time, and Alan Thornett, who worked in the Assembly Plant for 23 years and was likewise a shop steward for most of them assess the political impact of the life of their friend and comrade Bob Cullen.

- Pope Francis’s failed ‘realignment’Brais Fernández, a member of the editorial board of Viento Sur (Wind from the South) and a member of the Anticapitalistas in the Spanish State, comments on the passing of Pope Francis

- Reform – Labour is feeding the monsterThe centre cannot hold! In the wake of Reform’s massive gains in local elections, Dave Kellaway investigates the new political landscape.

- Manifesto for an ecosocialist revolutionABOUT THE BOOKThe race for profit is widening social inequalities and destroying the planet. As the productivist catastrophe is worsening day by day, democratic and revolutionary socialism must be rethought to meet needs within ecological limits. This Manifesto adopted by Fourth International in February 2025 by the Fourth International raises the banner of a civilisational … Read more