I came of age in 1990, a time when the Stone Roses and Happy Mondays ruled the airwaves, and Madchester was the epicentre of British music. Ian Brown of the Stone Roses famously declared, “It’s not where you’re from, it’s where you’re at,” capturing the ethos of a generation more concerned with the here and now than with tradition. For the Mondays, it was all about “pills, thrills, and bellyaches”—a hedonistic celebration of life that seemed endless. The Second Summer of Love had come and gone, leaving behind a heady mix of optimism and disillusionment. The 1980s had gone, this was the 1990s.

Blur’s second album Modern Life is Rubbish was a nod to the purists, hinting at shifting tides. Grunge was making its way across the Atlantic, but it wasn’t for me. The Stone Roses had retreated to the studio, not to return until 1994’s Second Coming, and Factory Records, once the heartbeat of the scene, was on its last legs. The label had staked everything on a new Happy Mondays album, sending the band off with £150K to record Yes Please! in Barbados with Talking Heads Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth producing. In hindsight, it was a reckless move. Our heroes were imploding, the scene fracturing, and what came next felt as manufactured as Stock, Aiken and Waterman.

“Madchester was no longer where it was at; the scene was shifting south, with London—Camden to be specific—becoming the new cultural hub.”

Music journalism was in its last long hurrah, with the NME and Melody Maker still being published weekly, their pages filled with the musings of writers watching their world shift beneath their feet. Madchester was no longer where it was at; the scene was shifting south, with London—Camden to be specific—becoming the new cultural hub. The Good Mixer pub was where the new breed of bands and journalists congregated, producing copy over pints and lines. Creation Records, with its roster already boasting the Jesus & Mary Chain and Primal Scream, was at the forefront of this new indie wave. 1993 and Alan McGee, the label’s maverick owner, had an eye for talent and discovered Oasis on a stage at King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut in Glasgow. But Oasis wasn’t the Stone Roses, nor were they Primal Scream. They were something different—rawer, more aggressive, and at the time unapologetically working-class.

I first saw Oasis in April 1995 in Sheffield (which just happened to be the last gig for original drummer McCarroll – see below), where they were supposed to be supported by The Verve. A fight in Paris put an end to that, and Pulp stepped in as the replacement for Richard Ashcroft’s band. It was a great gig—one of those nights where you could feel the electricity, where it seemed like something important was happening. I followed Oasis from Sheffield to Earls Court and then to the two massive gigs at Knebworth, where they cemented their place as the biggest band in Britain. Even the release of Oasis’ disappointing third album, Be Here Now, failed to put a dent in the hype. 400,000 copies were sold on release day, and I bought three of them: one on CD, the vinyl album, and a tape version so we could play it in the office. I even waited for WHSmith to open at Victoria Station—though I cringe at the thought now. But by the time we got to Finsbury Park in 2002, something had changed. The crowd had changed. The spirit of Madchester had given way to the brash, boozy bravado of “Loaded” lad. Beer was thrown rather than drunk, and the atmosphere was more aggressive, less about the music and more about the spectacle. My last Oasis gig was in 2006 in Lille, and by then the magic had faded. The band that had once felt like a revelation now seemed like a relic of a different time.

From the Warehouse to Lad Culture

The birth of the warehouse scene in the late 1980s and early 1990s marked a significant shift in British youth culture.Dance music, fuelled by the widespread use of Ecstasy, was run by working-class lads and lasses for the working class (and anyone else, the point was it didn’t matter who you were). It was a vibrant, grassroots movement that celebrated inclusivity, freedom, and community. This scene was inherently political, standing in direct opposition to the established norms of mainstream culture. It rejected hierarchy and embraced diversity, creating a space where people from all backgrounds and races could come together and dance to the beats of electronic music.

However, this celebration of freedom soon came under threat from the government. The Conservative government under Thatcher and then John Major sought to curtail this burgeoning movement, culminating in the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994. This legislation specifically targeted raves, banning gatherings centred around “music with a repetitive beat,” and was widely seen as an attempt to suppress a politically charged youth movement. The Criminal Justice Act was a clear message from the government: the right to dance, to gather, and to express oneself freely was not to be taken for granted.

Amidst this crackdown, British youth culture was once again in transition. The end of the Thatcher/Major era had left deep scars on working class youth (lack of opportunity/unemployment), and in the wake of this, lad culture began to slowly dominate. In 1994, Oasis emerged, perfectly positioned to become the poster boys of this new movement. Lad culture, with its emphasis on (misogynist) debauchery, machismo, and a rejection of intellectualism, became the defining characteristic of the scene. Oasis, with their unapologetic attitude and working-class roots, embodied this ethos and quickly rose to prominence. It seemed for every Menswear or the Longpigs the Gallagher’s loomed large.

The rise of lad culture, epitomised by Loaded magazine, marked a shift back to a more traditional—and some might say regressive—form of masculinity. Loaded celebrated a lifestyle centred around drinking, football, women, and having a laugh—an ethos that Oasis embodied perfectly. The magazine glorified a simplistic, no-nonsense masculinity that rejected sophistication in favour of a more primal, instinctive approach to life. Oasis, with their love of booze, swagger, and irreverent attitude, were the ideal representatives of this culture. The band’s antics—whether getting into brawls, insulting other musicians, or just talking about getting “mad for it”—aligned seamlessly with Loaded’s vision of what it meant to be a man in ’90s Britain.

“Lad culture, with its emphasis on hedonism, machismo, and a rejection of intellectualism, became the defining characteristic of the Britpop scene.”

This culture, while fun and carefree on the surface, also perpetuated a narrow view of masculinity that glorified excess and discouraged introspection. The emphasis on “beer and tits,” as Loaded so bluntly put it, turned having a laugh into a guiding philosophy, one that left little room for the complexities of life or the responsibilities that come with adulthood. For many, Oasis wasn’t just a band; they were the living embodiment of the Loaded lifestyle—a band of brothers who seemed to have it all, living out the fantasies of a generation that wanted to escape the drudgery of daily life.

But lad culture, with all its brashness and bravado, also had a darker side. It often flirted with sexism, homophobia, and an aggressive anti-intellectualism that shut down meaningful discussions on politics, identity, and social change. Unlike the dance scene, which stood against the authoritarianism of the Criminal Justice Act and championed a more inclusive, socially conscious ethos, Loaded culture, and Oasis specifically, offered a more insular escape, one that was resistant to progress and dismissive of anything that didn’t fit into their narrow view of what it meant to be “one of the lads.”

“Dance music as an underground culture used to be a safe haven for those who didn’t fit into the mainstream to have a refuge for our weirdness. Now, most of it is populated by the kids we once sought to escape from.”

reid speed

For me, the most troubling aspect of ‘lad culture’ was how it sought to erase the sensitive and intelligent working class man, branding him as unworthy of his masculinity. It perpetuated the idea that the working class was somehow inadequate, while reserving that space for the middle and dominant class.

Political Sounds

Should music be political? I believe it should. Music is more than entertainment; it’s a form of expression that reflects the times, challenges, and inspires change. When music engages with politics, it becomes a powerful force, giving voice to the voiceless and highlighting issues that might otherwise be ignored.

The rave scene, for example, was inherently political, standing as a form of resistance against government repression. In contrast, the rise of lad culture and the music of Oasis, while reflective of a specific working-class experience, often avoided direct political engagement, opting instead for the personal, the selfish, and the individual.

I need to be myself. I can't be no-one else · I'm feeling supersonic, give me gin and tonic. You can have it all, but how much do you want it? (Oasis - Supersonic)

But can music truly resonate without politics? I don’t think so. (John Lennon one of the Gallagher’s musical heroes was always political) Without political engagement, music risks becoming mere background noise (lift music?)—pleasant, but ultimately inconsequential. Music that dares to tackle political issues pushes boundaries and invites listeners to think critically about the world around them.

In the end, music and politics are deeply intertwined. Not every song needs to carry a political message, but when it does, it gives the music depth and purpose, transforming it from simple entertainment into a force for change. Without politics, music may still be enjoyable, but it lacks the substance that makes it truly meaningful.

The Britpop Context

While Oasis were swept up into the banner that was Britpop, they never sat comfortably alongside many of their contemporaries. The Britpop movement was diverse, encompassing bands that had as much to say politically as they did musically. Suede, with their glam-influenced sound and lyrics exploring themes of sexuality and urban decay, stood in stark contrast to Oasis’s more straightforward rock anthems. Elastica, with their punk-infused edge, and Sleeper, who often tackled issues of gender and relationships with a wry wit, offered a more nuanced take on the cultural landscape.

Caught by the fuzz Well I was, still on a buzz In the back of the van With my head in my hands Just like a bad dream I was only fifteen (Supergrass - Caught by the Fuzz)

Supergrass and Dodgy also brought their own distinctive voices to Britpop, blending genres and pushing boundaries in ways that Oasis never seemed interested in exploring. Supergrass, with their infectious energy and witty lyrics, and Dodgy, known for their sun-soaked melodies and socially conscious themes, both contributed to a Britpop tapestry that was richer and more varied than Oasis’s often singular focus. Blur, arguably Oasis’s biggest rival, epitomised this difference. While Blur engaged deeply with British identity, class, and the changing social landscape, Oasis remained largely apolitical, focusing instead on universal themes of love, loss, and defiance. Blur’s Damon Albarn was not afraid to challenge the prevailing order, using his platform to comment on the state of the nation, whereas the Gallagher brothers seemed content to sidestep these issues entirely.

The Spectacle of Celebrity

Oasis was never just a band; it was always about the Gallagher brothers. From the outset, Liam and Noel Gallagher were not just the faces of the band—they were the band. Oasis wasn’t a collective of musicians united in a shared artistic vision; it was a spectacle of celebrity, a soap opera centred around two larger-than-life characters whose public feuds and outrageous antics often overshadowed the music itself.

“Their spats were publicised and amplified, feeding into a culture of celebrity where the drama surrounding the music became more important than the music itself.”

The focus on the Gallagher brothers created a dynamic where the other band members were little more than supporting actors, easily replaceable in the grand narrative that was more about persona than performance. Paul “Bonehead” Arthurs, Paul “Guigsy” McGuigan, and Tony McCarroll were part of the original line-up, but their contributions were often diminished in the shadow of the Gallagher brothers’ omnipresent egos. When these members left or were replaced, it barely caused a ripple; the band continued as if nothing had changed because, in the eyes of the public, nothing had. Oasis was Liam and Noel—everyone else was dispensable.

This wasn’t just a band; it was a spectacle, and the Gallaghers were its main attraction. Their constant bickering, public insults, and reckless behaviour provided endless fodder for the tabloids and kept Oasis in the headlines long after the music itself had started to lose its edge. Their very public rows—whether on stage, in interviews, or behind closed doors—were played out for the world to see, turning their relationship into a form of entertainment that often overshadowed the songs they were supposed to be promoting.

The brothers’ antics often seemed more calculated for attention than born out of genuine emotion. Their spats were publicised and amplified, feeding into a culture of celebrity where the drama surrounding the music became more important than the music itself. The tension between Liam’s volatility and Noel’s brooding (or Liam’s brooding and Noel being volatile) created a storyline that was irresistible to a media landscape hungry for the next big headline. Oasis, as a result, became less about the art they produced and more about the spectacle of the Gallaghers’ lives—a spectacle that the brothers themselves were all too aware of and which they exploited to the fullest.

Noel and Liam always fitted the mold of the typical school bully and school clown. Even if Noel hadn’t kicked things off, he would have pulled every trick in the book to make sure Oasis came out on top. When the media conflated ‘Battle of Britpop’ erupted between Oasis’s ‘Roll With It’ and Blur’s ‘Country House,’ Noel had to eat humble pie when Blur emerged victorious. It was then that he resorted to making his abohrent comments about Albarn catching AIDS and dying.

While Blur might have started the chart rivalry, Albarn eventually saw the Gallagher brothers for what they were—just the school bullies in a different setting. In No Distance Left to Run, he reflected, “Noel Gallagher used to take the piss out of me constantly, and it really, really hurt at the time. Oasis were like the bullies I had to put up with at school.

This obsession with celebrity came at a cost. The music, once fresh and vital, became secondary to the personas that the Gallaghers cultivated. Their public disputes and larger-than-life egos consumed the band, creating an environment where creative collaboration was impossible and where the music often felt like an afterthought. By the time Noel Gallagher walked away in 2009, effectively ending Oasis, it was clear that the band had long since stopped being about the music. It had become a brand, a commodity fuelled by the relentless drama of the Gallagher brothers rather than any meaningful artistic pursuit.

The Epitome of New Labour’s Shallow Promises

Before the tantrums and falling outs, Oasis for a short while was at the heart of something new, more than just a band; by the late 1990s they became the poster boys for “Cool Britannia,” a cultural movement that sought to rebrand Britain as a vibrant, modern, and dynamic nation. This movement coincided with the rise of New Labour and Tony Blair, who successfully harnessed the energy of Britpop to project a sense of youthful optimism and renewal. Noel Gallagher, with his swagger and sharp wit, was cast as the epitome of this new, self-assured Britain—a man of the people who had risen from the working class to become a cultural icon. However, this alignment with ‘cool’ also reflected New Labour’s broader political strategy: a deliberate shift away from its traditional working-class roots toward a more centrist, market-friendly approach that prioritised middle-class appeal over working-class solidarity. In embracing figures like Gallagher, New Labour sought to create an image of inclusivity and modernity, but in reality, this was more about style than substance—a cosmetic rebranding that masked the party’s gradual abandonment of the very communities it once championed.

#OTD 1997. Tony Blair hosts ‘Cool Britannia’ reception at Number 10 for celebrities who backed New Labour

— Tides of History (@labour_history) July 30, 2019

Guests included Noel Gallagher, Ross Kemp, George Michael, Mick Hucknall, Ralph Fiennes, Lenny Henry, Vivienne Westwood, Nick Hornby, Helen Mirren, Ben Elton, Kevin Spacey pic.twitter.com/0SoCQQqDyY

“New Labour’s focus on image over substance was not just a cosmetic shift; it was a deeper cultural rebranding that left working-class communities behind.”

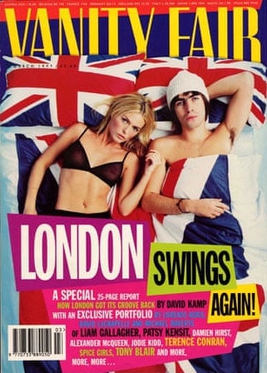

Tony Blair’s New Labour was keen to distance itself from the old, staid image of the Labour Party, symbolising a move away from policies that directly addressed the material concerns of the working class. Less beer and sandwiches, more champagne supernova. Instead, the rebranding was not just about policies; it was about creating a new cultural identity for the nation—one that was modern, inclusive, and aspirational, but also market-oriented and focused on attracting middle-class voters. A significant part of this rebranding involved a bold attempt to reclaim the Union Jack as a symbol of patriotic pride. This effort came five years after Morrissey’s controversial use of the flag during his performance at Madstock in 1992, an act that had been widely criticised for its flirtation with far-right symbolism. While Morrissey’s gesture was seen as embarrassing and divisive, New Labour sought to recontextualise the Union Jack as a unifying emblem of a revitalised, progressive Britain, free from the toxic associations of nationalism. However, this cultural project was more about crafting a marketable image of unity than addressing the deep-seated economic inequalities that continued to affect working-class communities.

Oasis, with their working-class roots and meteoric rise to fame, fit perfectly into this narrative. They were rough around the edges, yet wildly successful—a perfect symbol of the New Labour ideal that anyone could achieve greatness if they just worked hard enough. However, this narrative was deceptively simple and aligned with New Labour’s broader political shift towards centrist neoliberal policies that often left behind the working-class communities from which Oasis emerged. Noel Gallagher’s appearance at 10 Downing Street in 1997, shortly after Blair’s landslide election victory, was emblematic of this symbiotic relationship between New Labour and the Britpop movement. Gallagher, draped in the Union Jack, was the living embodiment of “Cool Britannia”—a movement that sought to celebrate British culture in all its diverse and modern forms. Yet his presence alongside Blair also symbolised New Labour’s focus on image over substance, where the politics of representation were used to obscure the party’s retreat from traditional working-class politics.

“Noel Gallagher’s appearance at 10 Downing Street symbolised not just a cultural triumph but also the shallow promises of both ‘Cool Britannia’ and New Labour.”

However, this embrace of Oasis by New Labour and the “Cool Britannia” movement was ultimately superficial. Just as Oasis’s music was often more about bombast than depth, so too was the “Cool Britannia” brand more about image than real change. New Labour’s policies, while initially promising a break from the past, often ended up reinforcing the status quo. This reflected a broader shift within the party away from the traditional working-class base toward a centrist, market-friendly approach that prioritised appeal to the middle class and business interests, the third-way. The close relationship between Blair and cultural figures like Noel Gallagher symbolised this shift—a move away from substance towards a focus on style and marketable images. The proverbial style over substance.

The Union Jack, despite New Labour’s efforts, has remained a contentious symbol. The flag’s association with nationalism and far-right movements has made it difficult to reclaim as a purely positive emblem of British identity. This challenge persists today, as evidenced by the recent election campaign of Labour leader Keir Starmer, whose materials prominently featured the Union Jack. Starmer’s use of the flag reflects an ongoing attempt to reframe it as a unifying force, representing a modern, diverse, and inclusive nation. The recent far right riots have somewhat soured the status of both the St George’s cross and the Union Jack. What was a deliberate attempt to detach the Union Jack from its historical associations with exclusionary and far-right ideologies and instead promote it as a banner of national pride that reflected the progressive values of a new Britain under a new, new Labour has thus far been an abject disaster.

Change begins. Watch my speech here. https://t.co/npCLojfGZk

— Keir Starmer (@Keir_Starmer) July 5, 2024

Morrissey, a figure who straddled the 80s and 90s, who had previously embarrassed himself with his Union Jack stunt1, later deepened his association with far-right views by supporting jailed Tommy Robinson in 2018 and backing the anti-Islam party For Britain in 2019. He even suggested that Nigel Farage would make a good prime minister. These actions further complicated the Union Jack’s legacy, highlighting how easily it can be co-opted by divisive, exclusionary ideologies.

Cornershop demonstrate the fire risks of Morrissey posters.

— Michael Bradley (@MickeyUndertone) September 5, 2017

Thanks lads.

Sleep On The Left Side ending tonight's MBRS @bbcradioulster pic.twitter.com/37Z0ZAWbKk

As the years passed, it became clear that “Cool Britannia” was more like a marketing campaign dreamed up by the British Council than a genuine cultural revolution. The optimism that surrounded Blair’s early years in office gave way to disillusionment, particularly as New Labour’s promises of a fairer society failed to materialise. The war in Iraq, the continuation of neoliberal economic policies, and the widening gap between rich and poor all contributed to the erosion of the hopeful image that had been so carefully crafted in the mid-1990s.

In many ways, Oasis’s role in “Cool Britannia” mirrored the trajectory of New Labour itself: starting with a bang, capturing the imagination of a nation, but ultimately being unable to deliver on the lofty promises of change. Noel Gallagher’s swaggering presence at Downing Street was a moment of cultural triumph, but it also symbolised the shallowness at the heart of both the band’s music and the political movement they had come to represent.

Oasis, like New Labour, was a product of its time—a time when image and perception often took precedence over substance. The band’s association with “Cool Britannia” and New Labour was less about genuine political engagement and more about creating a marketable narrative. In the end, both Oasis and New Labour left behind a legacy that is remembered as much for what it promised as for what it failed to deliver. The “Cool Britannia” moment, much like Oasis’s peak, now feels like a relic of a more naïve and optimistic era—one that believed in the power of culture to effect real change but ultimately fell short in the face of reality.

Jarvis Cocker, Real Life, and Protest

Perhaps the most striking contrast within the Britpop movement comes when we consider Jarvis Cocker and Pulp. Pulp’s music was a window into working-class life, filled with sharp social commentary and a deep understanding of the struggles and aspirations of ordinary people. Songs like “Common People” were not just anthems; they were narratives that captured the frustrations and dreams of a generation, offering insight into the complexities of class and identity in modern Britain.

Cocker’s lyrics were both observational and empathetic, providing a voice for those often overlooked in society. Pulp’s work was political in the truest sense—not in a didactic or overtly ideological way, but through a commitment to depicting reality as it was lived by millions. In contrast, Oasis’s lyrics, while powerful and evocative, often lacked this depth, focusing more on personal themes and abstract emotions than on the gritty realities of life in Britain.

Cocker’s protest against Michael Jackson at the 1996 BRIT Awards is a prime example of his willingness to challenge the establishment. Less of a “moon” and more of a bend and flounce, Cocker turned away from the crowd during Jackson’s messianic performance, bent over and made a wafting gesture from his behind, as if to tell the audience to “wake up and smell the excrement.” He then demonstrated his zip-up top and ran off the stage. While by today’s standards this might seem tame, at the time it was a shocking act of defiance. This was 13 years before Kanye West interrupted Taylor Swift at the MTV VMAs—context that underscores just how audacious Cocker’s protest was.

“This act of defiance was not just a publicity stunt; it was a deliberate political gesture that critiqued the absurdity and hypocrisy of celebrity culture.”

While figures like Noel Gallagher were calling for Cocker to be knighted, and celebrities like Neil Morrissey and Martin Clunes (men behaving badly—remember them?) led a “Free Jarvis” campaign, others took the stunt very seriously. Cocker was rushed to a police station and detained until 3 AM on charges related to “assaulting some kids,” a claim that was ultimately baseless. Reflecting on the incident later (see interview on TFI with Chris Evans below), Cocker explained his motivations: “I was just sat there and watching it and feeling a bit ill ’cause he’s there doing his Jesus act. And I could kind of see—it seemed to me there were a lot of other people who kind of found it distasteful as well, and I just thought: ‘The stage is there, I’m here, and you can actually just do something about it and say this is a load of rubbish if you wanted.'”

This act of defiance was not just a publicity stunt; it was a deliberate political gesture that critiqued the absurdity and hypocrisy of celebrity culture. In contrast, Oasis’s rebellious image often seemed performative—more about maintaining a certain attitude than about making any real statement.

Similarly, Chumbawamba, though often dismissed (unfairly) as a one-hit wonder, made headlines when they tipped a bucket of water over Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott at the 1998 BRIT Awards. This act of protest was a direct challenge to those in power, highlighting the band’s commitment to anarcho-punk and their willingness to use their platform to speak truth to authority. In contrast, Oasis’s bad boy swagger often lacked substance—more about image than action, more about attitude than art.

In 1997, while Noel Gallagher urged the Oasis crowd to back the striking Liverpool dockers, I attended a gig at ULU where Primal Scream and Asian Dub Foundation performed a benefit concert, donating all the proceeds to support the striking workers. The event was hosted by Irvine Welsh, the author of cult novel Trainspotting which had recently been made into a successful movie by Danny Boyle, produced by Andrew McDonald, with an adapted screenplay by John Hodge2 (the three would later collaborate on The Beach based on the novel by Alex Galand)

The day after the 1997 general election, Damon Albarn was interviewed by Swiss TV. He voiced his hope that the word “socialism” wouldn’t be forgotten by the incoming Blair government and expressed disappointment that the Blairs hadn’t sent their eldest son to a state school, recognising the importance of a good education was deserved by all. He ended by emphasising that those in pop culture have a duty to speak out.

Damon Albarn continues to push boundaries The Good, The Bad & The Queen, a later side project, and particularly on their 2018 album, Merrie Land. When the EU referendum results came in, Albarn was preparing to perform at Glastonbury 2016 with an Orchestra of Syrian Musicians. Reflecting on that moment, he noted how the Syrians were puzzled by the deep shock felt by many in the UK. Albarn later remarked that if he had anticipated the country’s direction before and after the vote, he would have returned earlier to voice his concerns more publicly.

“When the EU referendum results came in, Albarn was preparing to perform at Glastonbury 2016 with an Orchestra of Syrian Musicians. Reflecting on that moment, he noted how the Syrians were puzzled by the deep shock felt by many in the UK.”

Merrie Land captures the broader confusion of post-Brexit Britain. The album sharpens its focus on the nation’s disarray, with Albarn sometimes setting aside his usual subtlety for more direct commentary. The title track, for example, questions the uneasy alliance between working-class Brexit supporters and the privileged few who claim to represent them.

This year, during a performance with Bombay Bicycle Club at Glastonbury, Albarn once again shared his thoughts on important stuff away from music. He urged the crowd to consider the fairness of the conflict in Palestine, the importance of voting in the upcoming elections, and whether it’s time for a generational shift in global leadership.

https://t.co/LY4kdOaT68 pic.twitter.com/Ps2IfHtOgz

— Damon Albarn (@Damonalbarn) June 18, 2024

The Manics (for real)

While Oasis dominated the scene with their brash, swaggering anthems, the Manic Street Preachers offered a starkly different vision of what working-class music could be. Where Oasis embodied a simplistic, often reductive portrayal of working-class life—one focused on hedonism, defiance, and a celebration of “laddish” culture—the Manics took a more complex, intellectually rigorous approach. Their music, steeped in radical politics and introspective lyricism, was a deliberate counterpoint to the commodified version of working-class identity that Oasis represented.

The Manic Street Preachers emerged from the coal-mining communities of South Wales, a background that deeply informed their music and their politics. Unlike Oasis, who largely avoided overt political statements, the Manics embraced a decisively left-wing stance, urging a kind of radical intellectualism that was the antithesis of Oasis’s apolitical bravado. Their lyrics, often dense with references to history, literature, and political theory, challenged their listeners to think critically about the world around them. This was working-class music, but not as Oasis defined it—it was thoughtful, confrontational, and deeply engaged with the struggles and aspirations of ordinary people.

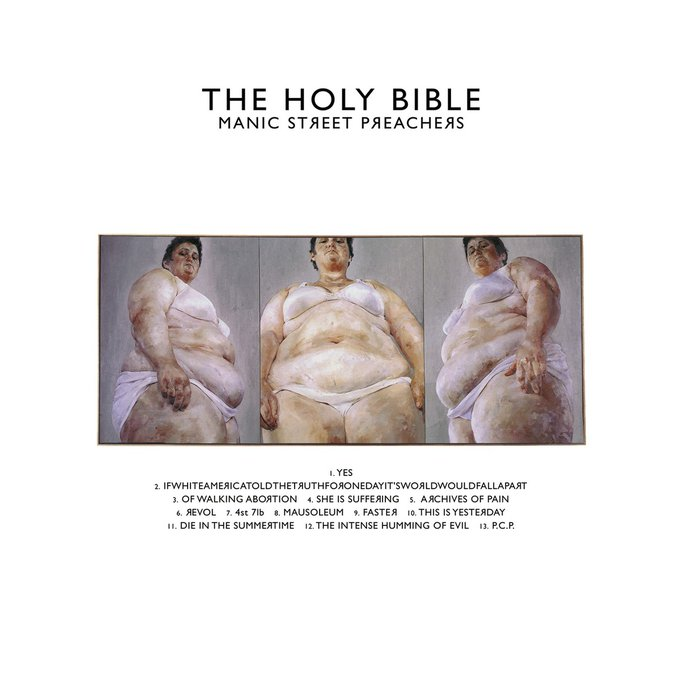

The Manics’ The Holy Bible was released on the same day as Oasis’ Definitely Maybe, and you couldn’t find two more contrasting albums. While Oasis offered a swaggering, anthemic celebration of working-class life, The Holy Bible delved into the darkest corners of the human psyche. With Richey Edwards’ intense and introspective lyrics, the Manics challenged the idea that working-class identity had to be tied to bravado and simplicity. Instead, they suggested it was not only acceptable but powerful to be working-class, intelligent, and deeply introspective—to feel the weight of the world and question it. The Manics showed that vulnerability, complexity, and critical thought were not just for the privileged, but for anyone willing to engage with the world on a deeper level.

There's more than a certain irony to The Holy Bible coming out the same day as Definitely Maybe, and it's an enormous pity it was the latter rather than the former which has ended up having the most influence. https://t.co/tZj4a2TP2A

— Octavius Ace (@8Ace___) August 30, 2024

The cover art on The Holy Bible, featured a striking image by British artist Jenny Saville, adds another layer of depth to the album’s intense exploration of human frailty and societal issues. Saville, known for her unflinching depictions of the human body, was a key figure in the Young British Artists (YBA) movement, which was gaining significant attention in the early 1990s. Her work often challenged conventional beauty standards and confronted the viewer with raw, visceral imagery, much like the album’s content itself.

This connection to the YBA movement links The Holy Bible to the broader cultural moment of the 1990s, “Cool Britannia.” In a time when much of British culture was celebrating newfound confidence and global influence, The Holy Bible served as a stark reminder of the underlying issues that still needed to be confronted.

A double page press advert listing the full lyrics to the album. One of the most incredible press adverts of the 1990’s!

— Britpop Memories (@Britpopmemories) August 30, 2024

2/2 pic.twitter.com/IyeG8kzujV

“The Manics took a more complex, intellectually rigorous approach, offering a stark contrast to Oasis’s commodified version of working-class identity.”

This commitment to radicalism and intellectualism set the Manics apart not just from Oasis but from much of the Britpop movement. While bands like Blur and Suede also explored themes of class and identity, the Manics did so with a sense of urgency and purpose that was rare in mainstream British music at the time. Their 1996 album Everything Must Go, released in the wake of the mysterious disappearance of lyricist and guitarist Richey Edwards, was both a commercial success and a powerful statement of intent. It showed that working-class music could be ambitious, complex, and deeply meaningful—a stark contrast to the often shallow, commercially driven narratives that dominated Britpop.

The Manics’ radical approach aligns them more closely with Pulp and Jarvis Cocker than with Oasis. Like the Manics, Pulp also offered a more nuanced portrayal of working-class life, one that acknowledged the complexities and contradictions inherent in the British class system. While Jarvis Cocker may have come from a mixed-class background—his mother was a Tory councillor in Sheffield even as Cocker himself leaned left—Pulp’s music was rooted in a deep understanding of working-class experience. Songs like “Common People” were not just catchy anthems; they were sharp critiques of class privilege and the commodification of working-class culture.

Simon Price, in his recent article for The Guardian, argued that the valorisation of Oasis as a quintessentially working-class band is ideological—it presents a narrow, often regressive view of what the working class is or should be. Oasis, in this framing, represents a working-class identity that is defined by simplicity, by defiance without depth, and by a rejection of intellectualism. In contrast, bands like Pulp and the Manic Street Preachers offered a broader, more inclusive vision—one that recognised the fluidity between working-class and lower-middle-class life, especially in communities where these identities often overlap.

The Manics, in particular, urged their listeners to embrace a form of working-class identity that was both radical and intellectual, challenging the notion that working-class culture should be defined by anti-intellectualism or political disengagement. Their music was not about escapism or nostalgia but about confronting the realities of life in Britain and seeking to change them. This stands in stark contrast to Oasis, whose appeal lay in their ability to provide anthems for a generation looking to escape those very realities.

“The Manics, in particular, urged their listeners to embrace a form of working-class identity that was both radical and intellectual, challenging the notion that working-class culture should be defined by anti-intellectualism or political disengagement.”

As we look back on the Britpop era, it’s clear that the legacy of bands like the Manic Street Preachers and Pulp offers a necessary counterpoint to the dominant narratives of the time. While Oasis may have captured the zeitgeist with their bombastic anthems and brash personas, the Manics and Pulp provided a deeper, more critical exploration of what it meant to be working class (flirting with the middle class) in Britain. Their music reminds us that working-class culture is not monolithic and that it can—and should—be a space for radical thought, intellectual engagement, and meaningful social critique.

Oasis, with their focus on universal themes of love, loss, and defiance, could never have written a song like “Kevin Carter,” which delves into the tragic life of the Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer, or “If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next,” which draws on the history of the Spanish Civil War to explore the dangers of fascism. These songs by the Manics not only reflect their commitment to exploring complex and often uncomfortable truths but also highlight the limitations of Oasis’s more straightforward approach to songwriting. While Oasis captured the zeitgeist with their anthems, the Manics provided a crucial counterpoint, demonstrating that rock music could also be a powerful tool for political engagement and intellectual exploration.

A Reactionary Fan Base?

Fast forward to today, and the legacy of lad culture is still evident in part of the fan base that eagerly anticipates the Gallaghers’ return. Many of these fans long for a return to the ’90s when, in their view, music was pure and British identity was untainted by the complexities of globalisation and multiculturalism. This nostalgia is not just for the music, but for a time when white working-class masculinity was dominant and unquestioned.

This longing for the past often manifests in reactionary politics. The same fans who revere Oasis frequently express disdain for contemporary movements that challenge the existing order, such as feminism, LGBTQ+ rights, and anti-racist activism. They view these movements as threats to the straightforward, “authentic” world they believe Oasis represents. The Gallagher brothers, while never explicitly endorsing such views, have done little to distance themselves from this reactionary element of their fan base. Their apolitical stance in many ways enables the perpetuation of this regressive nostalgia.

The Cash Grab and the Absence of Politics

Liam has demonstrated some allyship with the trans community through a few posts on Twitter/X. However, these seem to have been prompted by specific events/people rather than stemming from a consistent political consciousness. While Noel Gallagher has supported progressive causes in the past, Liam has generally shown little interest in politics. Neither brother has engaged in any deep or meaningful discussions about political issues in recent years. They’ve mostly maintained a careful distance from overt political statements, occasionally making offhand comments about politicians, but never truly delving into political discourse. I’m sure they would say it’s not their job. This contrasts sharply with other musicians from the Britpop era, such as Blur’s Damon Albarn and, of course, Jarvis Cocker, who have used their platforms to speak out on social and political matters.

“For the Gallaghers, the prospect of a world tour is not just a nostalgic trip down memory lane; it’s a business opportunity.”

But this time around, the motivations behind a reunion seem more transparent than ever. It’s not about making a bold musical statement (a new allbum, a different direction) or reclaiming the cultural zeitgeist—it’s about money. The success of recent world tours by artists like Taylor Swift and Adele has shown that there’s still a massive financial incentive for legacy acts to hit the road. Swift’s “Eras Tour” has become a cultural event, breaking records and generating hundreds of millions in revenue, while Adele’s return to live performance has also proven immensely profitable. In this context, an Oasis reunion is not just a nostalgic trip down memory lane; it’s a business opportunity.

For the Gallaghers, who have never been shy about their material ambitions, the prospect of a world tour is a chance to cash in on their enduring popularity. And why not? The nostalgia industry is always booming, and Oasis’s fan base, now older and more financially secure, is willing to pay ‘top dollar’ to relive their youth. But this commercial motivation only underscores the band’s detachment from the political and social issues that define the current era. By focusing on the financial windfall, the Gallaghers avoid engaging with the more complex and challenging questions about what their music and their legacy mean today.

Noel Gallagher, once hailed as a working-class hero, now exemplifies the “I’m alright Jack” mentality—comfortably esconced in his £17 million house (he lives in a house, a very big house….well almost), with millions in the bank, he is a man who has seemingly forgotten where he came from. Gallagher’s journey from the council estates of Manchester to the heights of rock stardom is a classic rags-to-riches story, but his attitudes and statements in recent years suggest a profound disconnection from the struggles of the working-class communities that once formed the bedrock of his fanbase.

Gallagher’s disdain for Jeremy Corbyn and the potential of a truly progressive Labour government is emblematic of this disconnect. In 2018, he famously told Paste magazine, “F*** Jeremy Corbyn. He’s a Communist,” dismissing the Labour leader’s vision for a fairer, more equitable society. A year later, his rhetoric grew even more vitriolic, declaring that he would rather reform Oasis than see Corbyn elected, branding him a “fing student debater, fing captain fishy, craggy old fing donkey, f off.” Gallagher’s contempt extended to other prominent Labour figures, including Shadow Home Secretary Diane Abbott, whom he described as “the face of f***ing buffoonery.”

“Gallagher’s transformation from working-class icon to wealthy celebrity is a cautionary tale of how success can distance one from their roots.”

These outbursts are not just crude; they reveal a profound irony in Gallagher’s position. Here is a man who built his career on the identity of being a voice for the working class, yet he now dismisses one of the few political figures in recent memory who has genuinely sought to address the systemic inequalities facing those very communities. Gallagher’s characterisation of Corbyn and his allies as “pipe-smoking communists” spouting “nonsense” is particularly telling. It reflects a mindset that, once safely insulated by wealth and privilege, sees no need for the kind of radical change that might disrupt his own comfortable existence.

Gallagher’s remarks about politicians being “f***ing idiots” and his view that they should be “forward-thinking, modern, and contemporary—looking forward” further underscore his disconnection from the reality of working-class life. His definition of “forward-thinking” seems to equate to maintaining the ruling class, where wealth and opportunity remain concentrated in the hands of a few while the many continue to struggle. This is a far cry from the man who once sang about the dreams and aspirations of ordinary people, the ones who “live forever” but still have to fight to survive.

In the end, Noel Gallagher’s transformation from a working-class icon to a wealthy celebrity who derides progressive politics is a cautionary tale. It highlights how easily the trappings of success can lead to a loss of solidarity with the very people who helped elevate him to stardom. Gallagher’s harsh words against Corbyn and the Labour movement serve as a reminder that wealth can create a bubble—one where the struggles of ordinary people are easily forgotten and where the need for social change is dismissed as “communist nonsense.”

As Gallagher continues to live in luxury, it’s worth questioning how far he has strayed from the values that once defined his music and his appeal. His story is not just about one man’s success; it’s about the broader cultural shift where working-class heroes are co-opted by the very system they once seemed to stand against, leaving behind the people who need them most.

Noel bemoaned the fact that working-class kids today might struggle to become the next Oasis, citing the rising costs of guitars and the disappearance of affordable rehearsal spaces. However, while Noel highlights this issue, he offers little in the way of solutions or initiatives to help change the situation. For all his concern, it seems the rock icon is more focused on lamenting the state of the industry than taking steps to make music more accessible for the next generation of working-class talent.

For every Rashford we find a Barton.

Nostalgia as a Reactionary Force

Nostalgia, particularly in the context of lad culture, is not merely a sentimental journey back to simpler times—it often serves as a regressive force, reflecting deep-seated anxieties about the present and future. This longing for a past that seemed more straightforward, homogeneous, and less fraught with the complexities of today can carry reactionary undertones, resisting change and romanticising an era where social hierarchies felt more secure, especially for white working-class men.

The Oasis reunion is more than just a way to fund Noel’s divorce settlement or just another musical event—it’s a commercial enterprise that taps into these undercurrents of nostalgia. While there’s no denying that the tour is about making money, it’s also about capitalising on a collective yearning for a time when life felt simpler, when Oasis provided the anthems for a generation trying to find its place in a rapidly changing world. Globalisation was still viewed as a positive thing, and Brexit was but a fever dream of Farage and the ERG. The enthusiasm surrounding the reunion reveals a desire to reclaim a sense of identity and purpose that many feel has been lost in the modern world.

This sentiment resonates with the rise of political movements like Reform UK, led by Nigel Farage, which also draw on a yearning for a return to “traditional” values and a resistance to the multicultural and globalised reality of contemporary Britain. We saw this phenomenon in action when it was leaked that the Labour government might ban smoking in beer gardens, an announcement that sparked more hysteria than over the upcoming budget. One Tory backbencher even compared Starmer coming for her cigarettes to the Niemöller poem about the Holocaust. Farage, much like the Gallagher brothers, has capitalised on a sense of disenfranchisement among those who feel left behind by rapid social and economic changes. Reform UK, with its rhetoric of reclaiming British sovereignty and returning to a perceived golden age of national identity, mirrors the reactionary nostalgia that fuels the anticipation for Oasis’s comeback. Both movements are rooted in a desire to stop the clock, to turn back to a time when cultural and social lines were more clearly defined, and the uncertainties of modern life were less pronounced. After all, everyone thought they had found something worth living for…

“The nostalgia that drives both the longing for Oasis and the support for Reform UK reflects a discomfort with the present and a resistance to the complexities of a world that is increasingly interconnected and diverse.”

This connection between the Oasis reunion and the rise of figures like Farage is not merely coincidental; it is emblematic of a broader cultural shift. The nostalgia that drives both the longing for Oasis and the support for Reform UK reflects a discomfort with the present and a resistance to the complexities of a world that is increasingly interconnected and diverse. In this context, the Oasis reunion can be seen as more than just a nostalgic revival of ’90s music—it is part of a wider societal trend that seeks to recapture a sense of stability and order that many feel has been eroded.

As excitement grows for the return of Oasis, it is important to consider what this reveals about the current cultural and political landscape of the UK. The reunion may bring joy to many, but it also serves as a barometer of the unease that continues to shape British society. The nostalgia that drives both musical and political movements can be a powerful force—one that has the potential to unite and inspire, but also to divide and reinforce reactionary impulses in a rapidly changing world.

I don’t want to be a killjoy—if Oasis is still your favourite band, or you’re eager to relive your youth, then by all means, fill your boots. Just make sure those boots are sturdy enough to walk you home after forking out £150 (or £6000 if you missed out on the rush last night) for standing tickets—at that price, they better be made for walking, because you will not have money for an Uber! There’s no denying the impact Oasis had on a generation, and for many, their music is inextricably linked to some of the best moments of their lives. But for me, this indie boy won’t be partaking in the “Cigarettes & Alcohol” this time around. The allure of those anthems has faded, and what remains is a reflection on what Oasis truly represented—a band that, while undeniably iconic, often prioritised spectacle over substance, image over engagement. As we look back on the era of “Cool Britannia” and the band’s role within it, it’s clear that the nostalgia for that time should be a complex mix of both fond memories and critical hindsight.

I don’t want to be a killjoy—if Oasis is still your favourite band, or you’re eager to relive your youth, then by all means, fill your boots.

Footnotes

- “Waving the union jack during his show at Madness’s Madstock festival in Finsbury Park, London, in 1992, felt like a more aggressive move (this was before Britpop’s Cool Britannia-era reclamation of the flag, and its association with the far right was still strong). And it was done in the knowledge that the Madness crowd contained a significant fascist/skinhead element. When – according to Pat Long’s book The History of the NME – the paper’s sole black writer Dele Fadele persuaded NME’s editors to publish a critical cover story about it, Morrissey refused to speak to the magazine for 12 years.” https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/may/30/bigmouth-strikes-again-morrissey-songs-loneliness-shyness-misfits-far-right-party-tonight-show-jimmy-fallon ↩︎

- If you’re looking for a quintessential ’90s movie that encapsulates the dark, gritty, and morally complex storytelling that defined much of the decade’s cinema, Shallow Grave is a must-watch. Directed by Boyle in his feature film debut, it starts with a simple premise: three flatmates in Edinburgh find their newly accepted fourth room-mate dead in bed, leaving behind a mysterious suitcase filled with cash. But this isn’t just a thriller—it’s a masterclass in how greed, paranoia, and mistrust can unravel even the closest relationships. The ’90s were a time when indie films began to flourish, and Shallow Grave is a prime example of the era’s penchant for blending dark humour with intense psychological drama. ↩︎

Art (54) Book Review (122) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) EcoSocialism (56) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (59) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (70) Gaza (61) Imperialism (100) Israel (127) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (55) Labour Party (113) Long Read (42) Marxism (50) Marxist Theory (48) Palestine (175) pandemic (78) Protest (152) Russia (340) Solidarity (145) Statement (49) Trade Unionism (142) Ukraine (347) United States of America (133) War (368)

Thanks Simon and ACR for this excellent analysis!!

An excellent essay reflecting on the dismay cultural phenomenum of Oasis. I must be the same generation as you Simon, I played in a wannabe BritPop band at the time and remember the era fondly, especially Suede, the Manics and Pulp. I remember the Cool Britania party and the Lads Mags culture somewhat less favourably however. Thanks for posting the links to some of the better moments, cheered me up after listening to Radio 2 on the day of the reunion announcement with their non-stop thinly veiled promotion, and desperate reaching for nostalgia that you correctly say is political in nature.