I was recently at a meeting addressing the problems of both healthcare and in social care in Britain, specifically in England and Wales.

Barnes and Mercer (2003) in Exploring Disability wrote: “[…] the words ‘care’ and ‘carer’ are regarded by the disabled people’s movement as paternalistic and dependency creating when used with reference to disabled people. Social ‘support’ is currently considered the more appropriate phrase for […] related services. Adult disabled people require ‘helpers’, ‘support workers’ or ‘personal assistants.’

I have used the terms “care” and “social care”, solely because these are words in common use. The terms social support and assistance to ensure that disabled and older people can live lives as independently as possible, would be better. I did this because this is already a complex discussion so I have not sought to complicate it further, but it is important to use the correct terminology as words carry implicit and explicit meaning.

Health

For health care, a number of issues came to a head during the pandemic;

- lack of government investment in the NHS,

- The mortgaging of NHS hospitals to the Private Finance Initiative which is leeching money from the service

- the privatisation of profitable parts of the NHS.

The creation of a private healthcare system in competition with the NHS not only drains resources (doctors, nurses) but, since many medical professionals work in both sectors, led to longer waiting lists for non-emergency procedures on the NHS. This decreases access for many while increasing it for those that can afford private health care or get it from their jobs.

During the pandemic the sorry state of the NHS became evident as it was stretched by dealing with those affected; by the pandemic itself. Routine healthcare became harder to access and non-emergency surgeries were postponed leading to a massive backlog of procedures that while not “emergencies” are important for more people to live without pain. Emergency medical procedures like heart and lung diseases, cancer treatment, and dialysis continued but not the daily routine access to preventive healthcare that keeps us healthy.

Lack of government investment and privatisation has led to a situation where these routine preventative treatment and surgeries that are deemed non-essential couldn’t happen during the pandemic. The availability of hospital beds was insufficient to cope with a major pandemic and medical professionals of all types were called into support overburdened and besieged hospital staff. GP surgeries were closed for in person appointments for significant periods to limit the spread of the virus but this meant that new or aggravated conditions were less likely to be picked up.

In fact waiting lists for non-emergency procedures existed prior to the pandemic and then became worse. Those that had the money to pay and those working for companies that provided access to private health care were able to ”jump the queue” past those that could not afford to pay. Rather than reduce waiting periods in the NHS, the existence of the private healthcare sector increased lines. Moreover, since the same people work both for the NHS and private providers, the private sector drains the NHS.

The situation in adult social care is far worse. There is a right to health care free at the point of demand and no right to social care. Access to government funded social care depends on income and wealth (assets) and the level of need which relates to impairment.

A short historical diversion

There are two groups of people who need adult social care: people with impairments and older people.

If we look historically, we see that while things have changed substantially for older people (through the creation of pensions) and disabled people (the creation of disability benefits including the distinction of short-term versus long-term support), there are still issues relating to the nature of the capitalist system that impact access to social care.

In the early days of the capitalist system there was a debate among economists and those working on social policy as to whether the poor have the unconditional right to subsistence or whether they need to do something which makes them eligible for this. – This relates to notions of entitlement and eligibility respectively and we still see this criterion commonly used today in discussion of social policy.

We see this discussion in Britain following the introduction of the 1795-7 Poor Law Amendment which attempted to deal with seasonal agricultural labour, still very significant. The transformation towards a full market system did not guarantee there was sufficient employment which guaranteed subsistence to workers couldn’t find paid employment. The right to outdoor relief (meaning that they didn’t have to enter poor houses to get support) embodied in the Speenhamland System established by these Poor Law Amendments tied relief to the size of the family and the price of wheat (the primary source of subsistence).

These discussions deliberately attempt to shift the responsibility for poverty away from the capitalist economic system being incapable of creating full employment towards that of blaming the unemployed for their poverty.

This takes place not long before a transformation in how political economists explained the determination of wages which shifts in the 1820-30s away from one based on the notion of subsistence and reproduction of the working class to the idea of a wage being determined by the supply and demand of capital used for the employment of labour (specifically that the fund for the employment of labour in relation to the number of people that needed employment) determined the wage that people got.

This shift changed not only the description of wage determination where the system had to provide for subsistence and reproduction of the working class towards one in which the actions of workers was the cause of low wages. As such, it was not the fault of the system that people were poor, it was due to their own actions (e.g., having too many children, being drunk, lazy, indolent and dissolute) and as such all unemployment was voluntary as the wage determined by supply and demand was a full employment one.

While most people may have heard of Malthus’s Principle of Population and his “Iron Law of Wages” which blamed the poor for their poverty (“people are poor because they have too many children”), they probably do not know is that the first attack against the right of subsistence was by Jeremy Bentham in 1797. This was a direct response to the 1795-7 Poor Law Amendment called “Observations on the Poor Bill.”

The argument is that human beings not born to wealth must labour as their contribution to society; in exchange for which they get a wage. The question thus arises as to whether those that are unable to labour for their subsistence still have the right to subsistence and this. becomes what is known as the 1834 Poor Law Amendments or the New Poor Law.

So, if you were able-bodied, you had to work. A whole serious of quantitative and qualitative conditions were established determining whether you were able-bodied enough to work or whether you were entitled to support. If you were able-bodied and couldn’t find a job, you had to enter the poorhouse to work there to contribute to society to get your subsistence. If you were unable to find employment to feed your family, you were forced to enter workhouses where you were put to work and all outdoor relief was eliminated. If you were not able-bodied and able to work, you were entitled to support from the state in the context of the workhouse (Bentham argued that even those with severe impairments could work in a workhouse as long as they were of sound mind) or insane asylums.

This may seem extraneous to a discussion of care, but it actually isn’t. It is a very clear example of the treatment of those who do not have the essential thing that enables one to survive in the capitalist system, the ability to labour. They would not let you starve on the street; they also would not provide extra support to the family to care and assist those who could not work. We can see the roots of institutionalisation of people with impairments that are unable as well as the treatment of orphans and older people

Pensions were created in Germany under Bismarck in the 1880s enabled older people to be financially independent from their families, easing the costs to families, and allowed for a turnover of intergenerational labour. Disability benefits in Germany were instituted at the same time. The creation of the welfare state further solidified a social safety net which is necessary as the capitalist economic system is prone to endemic crises. This was part of a shift away from the arguments that poor people were responsible for their poverty. However, the treatment of disabled people has often been based upon the view that they are a burden on society. We do not have to go to extreme of allowing forceable eugenics sterilisation of disabled people in the SCOTUS Decision of Buck vs Bell (1927) or the Nazi’s Aktion T4 programme which murdered disabled people . Even to this day with eugenics derided, women that are disabled still face pressure not to have children. In recent decades we are again in a period where those that are unable to work are viewed to be a burden on society and benefits and social security have been rationed and privatised.

The Benefits System

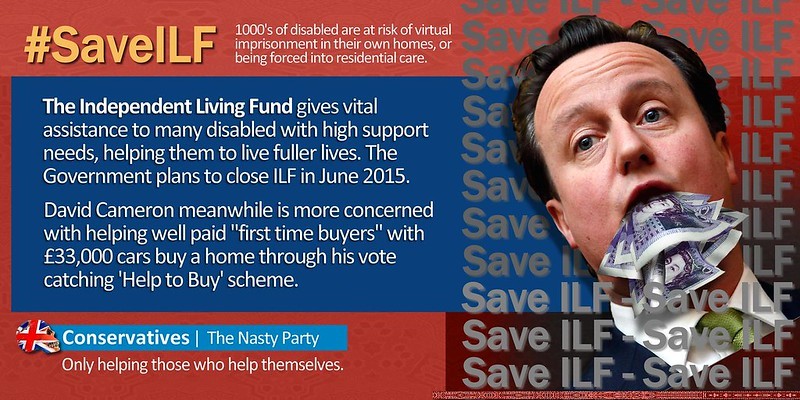

The benefits system has never adequately met the needs of disabled people – as indeed it has not for those who are out of work for long periods of time. There were however some benefits that partially addressed some of disabled peoples’ needs – notably Disability Living Allowance which was abolished for new claimants in 2016 and the Independent Living Fund abolished in 2015.

The most recent change in the British Government’s benefit policy was the introduction of Universal Credit (UC) in 2016 which was predicated on getting people back into employment as though those that were unemployed were work-shy and lazy. Employment Support Allowance (ESA) was introduced and you were then assessed on whether you were able to work or not and this determined how much benefit you get. This introduced a new tier of those receiving benefits called the Work Related Activity Group (WRAG) if they think you will be able to go to work. DLA was replaced by the Personal Independence Payment and mobility and level of care was reduced to two tiers in the new system.

Since the point of UC was to get people into work, the amount received as benefit had to be lower than what you would earn as wages if you were in paid employment (the modern application of “Less Eligibility” developed by Bentham). There are more issues that were added but these are less relevant for disabled people unless they were put into the WRAG group. Since the level of benefits was lower on UC, many disabled people already on benefits stayed on Legacy Benefits (the pre-UC system) which were more generous to disabled people. But when a £20 uplift was given to those on UC benefits during the pandemic, disabled people on Legacy Benefits were left behind.

The Health and Social Care Bill

Discussions of care tend to focus on funding, rather than what elderly people and disabled people want and need to be able to live independent lives. The voices of those who will receive support and assistance are rarely heard or heeded and neither are the voices of those working to provide support and assistance, Those two most important set of voices are routinely ignored.

The latest attempt to address the nightmare of the care system in Britain is the Health and Social Care Bill which integrates health and social care (thereby medicalising social care rather than using the social model of disability) and raises funds for increasing investment in health and social care through increasing National Insurance. Moreover, most of the immediate funding will be going to the NHS and funding for social care will “kick in in the near future”. Increases in NI means that you will have less take home pay (in an inflationary period where real wages are already being reduced). Moreover, given the tendency in the previous decades to replace employees with hiring self-employed or sub-contractors, this means that employer contributions are reduced; in other words, there is an incentive for businesses to hire short-term subcontractors rather than as employees.

By integrating Health and Social Care in this way, neither system will receive the funding needed to ensure the services needed by people in our society are available.

The catastrophe in social care

As well as integrating health and social care, the bill puts a cap (or limit) on how much you have to spend for social care at £87,000. Access to publicly funded social care in Britain depend on assets and income; so if you have assets over £23,250 you are not eligible for publicly funded social care. This means testing forces the majority of those that are older people in need of social care to fund it themselves.

In stark terms, this means is that those whose income and assets fall between £23,250 and £87,000 will have to pay for the costs of their care and will have little or no choice but to sell their homes (if they have them) in order to cover the costs of their social care. The further introduction of care charges for disabled and older people to cover support and assistance beyond what the local authorities will cover has been introduced by the Dept of Health and Social Care and reaffirms the £23,250 allowable assets. The only way to avoid these costs is if you are eligible for Continuing Health Care (CHC) which is funding by the NHS and is only available if medical professionals determine your assessed needs require it.

Faced with rising costs and increasing demand, the care system is unable to cope and is essentially failing; according to The Kings Fund:

“The number of people who need social care has risen over recent years, though this has not always been reflected in the number of people using care services. 1.9 million people requested support from their council last year, an increase of more than 100,000 since 2015/16. This rate of increase has in part been driven by demographic trends. People are living longer with multiple or complex needs and therefore might require short or long-term social care.

[…] However, demand for social care is not driven exclusively by an ageing population, the prevalence of disability among working-age adults has increased over recent years. The most recent data shows that the prevalence of disability among working-age adults is 19 per cent, up from 15 per cent in 2010/11. The same figure for older adults has remained static at around 44 per cent over the same period.

As well as increasing demand, the unit cost of providing care services is also going up, driven mainly by workforce costs. Care workers, who make up the majority of the workforce, have benefited from the introduction of the National Living Wage: average care worker pay has increased from an average of £6.75 an hour in September 2012 to £8.50 in 2020. However, it has now fallen below the average pay of shopworkers and cleaners.”

When the Health and Social Care Bill was presented to Parliament there was no discussion about the type of support and assistance people will receive and how it will be delivered. It is clear that there is no desire to make access to social care a right.

The other bizarre thing was the discussion on the bill made it sounds as if social care only was relevant to older people. There was little or no discussion that the majority of those receiving social care were those with impairments that are disabled by our society.

Discussions have abounded from more progressive sources than the government about Care-led recoveries and about the creation of a National Care Service.

There is a need to change the nature of the discussion about our collective right to care which doesn’t actually exist in advanced capitalist societies. We need to demand that the societies we live in need to challenge how both older people and disabled people are viewed in the capitalist economic system.

We also need to distinguish between social care and health care. Social care exists to ensure independent living; health care addresses medical issues. There is some overlap but these have different purposes. There are some differences in the needs and wants of disabled people compared to the those of older people and these do relate to points of overlap between the health and social care following an illness or injury.

Social care for disabled and older people is in catastrophic shape in Britain. While there is still some social care provided by the state through local authorities, the overwhelming majority of care has been privatised and care homes and agencies that provide social care either at people’s homes are run as profit making enterprises. The privatisation of care has led to both the quantity and quality of care provision to decline precipitously. Moreover, what is available and how much is not based on need but rather upon profitability criteria.

Whether or not you receive the support and assistance you need is dependent upon whether the private care providers make a profit. The private care providers have been threatening to withdraw from local government contracts because they are not being paid enough to make sufficient profits; the old “we would love to pay workers more … but” story. Care is something that cannot depend on the profit motive. Inevitably what happens is that profit is the main consideration, not those getting support and assistance nor those actually providing it.

The Mirror reported that private care home handing back local government contracts have tripled in the last 22 months leaving people that do not belong in hospital unable to be discharged as there was nowhere for them to go. According to the Mirror:

“The Mirror’s research shows the shocking depth of the social care crisis. In 2019, there were 731 contracts for residential care and care in the community handed back, while in just 10 months last year the figure was 1,939.

The returned care contracts last year left 4,720 vulnerable adults suffering distressing upheaval. Some families were given just 42 hours to find a new home.”

If the private care sector withdraws from local government contracts, that will mean that accessing care will require finances that neither disabled people nor older people have – care will become a luxury good if you have enough to buy it.

Part of the problem is the large number of job vacancies in care caused by several things.

- The work is low paid and difficult, those working in the sector are treated as unskilled and undervalued;

- Brexit has cut the number of potential care workers (67% of care workers in London are immigrants (evenly split between EU and non-EU; 19% in the rest of England);

- Large numbers of care workers left the profession due to government mandated vaccinations.

The quality and quantity of the provision of social care has got so bad that many women whose loved ones need support and assistance have stopped working in paid employment and are providing support at home. While they can claim a carer’s allowance it is exceedingly low and not enough to live on.

Care is a sector of the economy in which what is produced by care workers is consumed by those in receipt of support and assistance immediately. There is no surplus value or surplus product produced so profits are made by squeezing worker’s wages. Most care workers who work in people’s homes are paid only for the times that they are actually providing care and not for travel time between visits and making them pay parking fees. This leads to poor working conditions and the rationing of the amount of care that is provided (e.g., shorter visitation times, limits to what is provided in those visits). This means that care workers’ wages are extremely low, their conditions of work are hard and they do not have sufficient time to actually provide more than cursory care.

The reasons for low pay derive from the type of work that care workers do and the fact that it is traditional women’s labour. Since women do this work at home for free, it is deemed as unskilled labour and it is assumed anyone can do this work. The skills essential to the work are not skills that are highly regarded in the capitalist system; that so many care workers are women is relevant as well.

Privatisation has atomised this workforce; Agency workers often get short-term assignments rather than longer term work. People work on their own or in small groups working shifts. Unionisation is difficult in these circumstances.

Care workers are not seen as professionals doing a complex and highly skilled job. Rather than essential and professional workers providing an important service to people that matter in our societies, they are seen as care takers of people that are less important (or even a burden) to the economic system.

Those in need of support and assistance have a hard choice, take the inadequate provision offered by the private care sector or find something for yourself by using the direct payment offered by the government via a local authority. The latter entails a lot of work and finding people to do the job often means having to supplement the amount paid to them in order to contract sufficient levels of care.

Disabled people have fought long-term struggles around their right to support and assistance, against deinstitutionalisation, the provision of inclusive education and around the nature of understanding disability as a social creation rather than a medical problem. The restoration of the Independent Living Fund which provided support so that disabled people could live inclusively in communities rather than in residences for disabled people is still an essential demand for disabled people. It parallels the struggle over collective inclusion in society itself rather than an individual problem of not fitting into the mould of what society says that you must do. Many of these struggles over inclusion (where society adapts to you and includes you) rather than integration (where you must adapt to the society) are contested and ongoing. But for disabled people, the issue is overcoming social oppression where disabled people are excluded from society rather than a part of the communities where they live.

Maybe it seems obvious, but we are long past time the time that those receiving support and assistance and those providing it and the communities in which people live are the main voices in determining what support and assistance is needed, how it should be done and how this is part and parcel of a vision of inclusive communities. This view which is termed co-production must be done locally (while funded nationally) and planned in communities with decisions being made by disabled people, carers and the community. This should be the lynchpin of any discussion on the creation of a social care system, but that perspective is rarely heard among all the various ideas of what to do about social care .