Source > uACT

I am writing as a member of the Free Psychotherapy Network (FPN) and the campaign for universal Access to Counselling and psychoTherapy (uACT), but the responsibility for the opinions expressed is mine alone.

Is there a mental health crisis?

I think we probably have to allow that there is a mental health crisis of some kind going on in the UK, and by the way, all around the globe it seems.

In the form I am meaning mental health crisis here, it is a relatively recent phenomenon. I am thinking, for example, of how often we hear about people’s mental health in the Mainstream Media (MSM), and also perhaps especially on social media, particularly if you are plugged into the mental health/therapy/service user echo chamber – as many of us are these days.

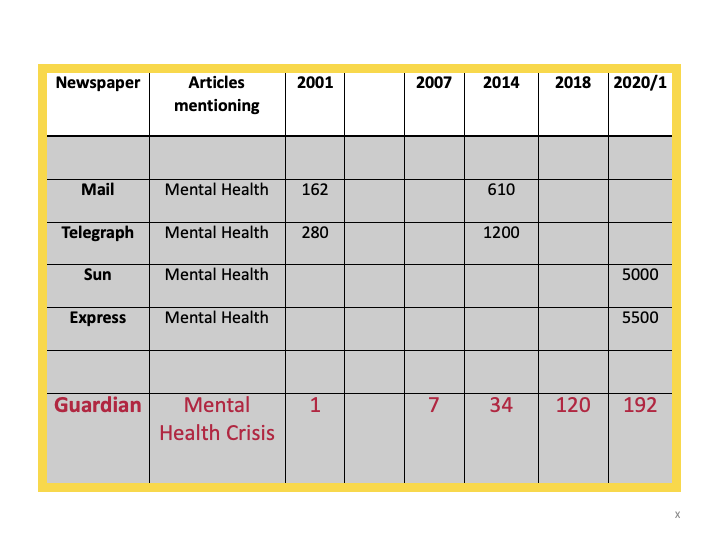

I recently had a go at gauging how often “mental health” and “mental health crisis” were mentioned in the press, in MSM headlines, and how the number of mentions has mushroomed over recent years. It was a very sparse, quick survey in the end, but nevertheless quite dramatic.

I think mental health as a regular news item probably got going in the 1990’s but mushroomed after 2000.

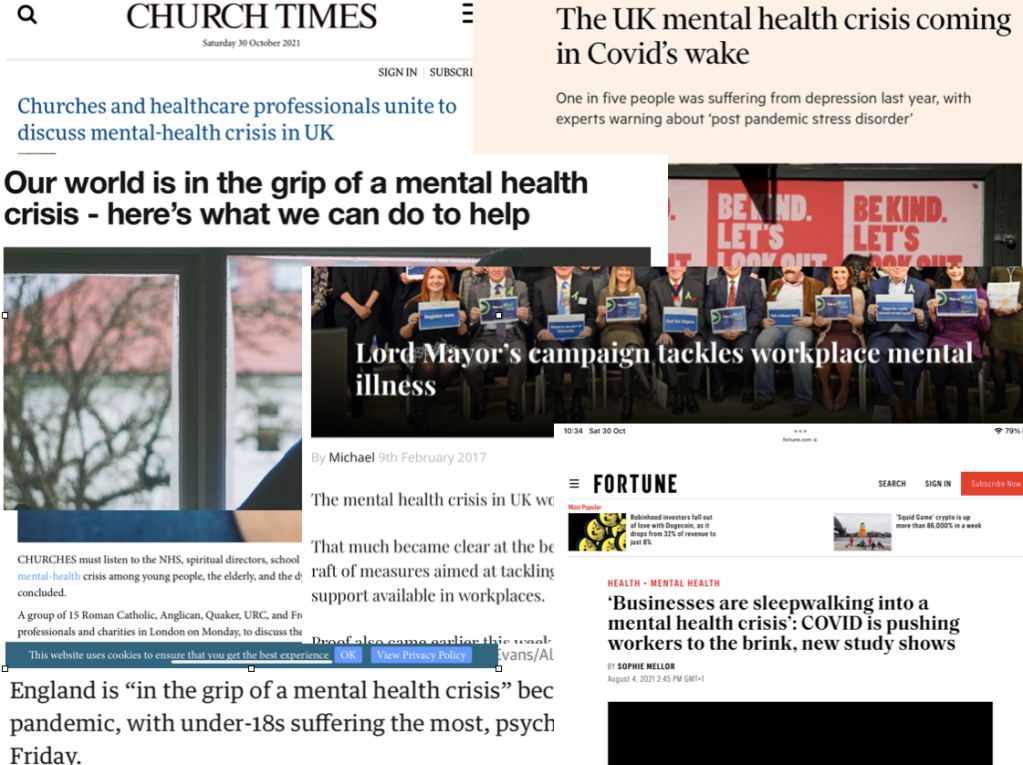

Here are the kind of headlines announcing the mental health crisis we have been getting used to in recent years:

Since the financial crash in 2008, there have been regular headlines about the state of mental health among young people, especially women, about eating disorders, suicide, self-harm as well as depression, anxiety and anti-depressant prescriptions:

And there has been a proliferation of celebrity mental health reports, with confessional headlines from across the spectrum:

What is this mental health crisis about?

But what is this mental health crisis about? What is it saying about our society and our changing relationship with emotional life, the priority we are giving to our own and other people’s psychological experience and pain?

It’s clear that awareness of mental health issues has been rapidly growing across the globe. As well as media coverage, there have been scores of reports in this country from charities like MIND and many others, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, central and local government and so on. Similarly from Europe (eg OECD reports) and more widely from the World Health Organisation – all pronouncing on the increasing incidence of common mental health conditions like depression and anxiety. It’s now everyday among younger people in the UK to be talking about their experience of MH problems and their diagnoses.

The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies service, introduced in 2008, has changed the scene as far as common mental health (CMH) conditions and their treatment is concerned. Since 2014, over 1 million people a year have been referred, or have self-referred, to IAPT. In 2019-20 there were 1,700,000 referrals.

We might expect then that all this media coverage indicates a reduction in social stigma around mental health problems. After all, almost every news report these days seems to include a mention of the mental health dimension of the item covered. On Radio 4 as a write this paragraph, the BBC are reporting “a survey of 4000 people on the cost of living. 56% reported cutting food and car journeys. Two thirds said their MH had been affected.”

But things are not so simple. There is significant stigma still in relation to psychosis, especially diagnoses of schizophrenia. There’s certainly stigmatisation of people in marginalised communities like the homeless, substance misusers, people experiencing poverty or disability – and severe and enduring MH conditions generally. And of course if you are black or brown there is always likely to be stigma.

There are also differences in levels of stigma within minority ethnic communities.

And we might ask, does the language of mental health and medical model diagnosis translate into awareness of psychological life, feelings, relational dynamics and and the dynamics of power?

Is there MORE psychological distress and suffering in recent decades than in the past?

This a difficult one. Firstly, we have very little comparative data before WWII. Data begins to really take off from the 1970s when anti-depressants begin to hit the consumer market and behavioural scientists and clinicians begin the big randomised controlled trials of behavioural therapy – notably Aaron Beck, “father” of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

The beginnings of so-called “evidence-based psychological treatments”, the mental health market and the mental health crisis are chronologically coincident. From a different angle, we might add to this, as far as increasing awareness is concerned, the role of humanistic growth movement therapies and alternative cultures around mind, body, spirit therapies from the late 60s and 70s.

Psychological trauma and distress, depression and anxiety, are not something new. We human beings have been living in societies for ever and day that normalise oppression and exploitation, through a combination of brute violence on the one hand and cultural narratives of “there is no alternative” on the other. Going back over the last century or two, I don’t imagine that the emotional and psychological stresses of ordinary people’s lives have been any less violent and traumatising.

For the political class, it has always been important to minimise and/or deny the damage we are doing to ourselves and our world in the name of necessity, in the name of maintaining the known and familiar (the status quo), or carrying on in the name of progress or economic growth.

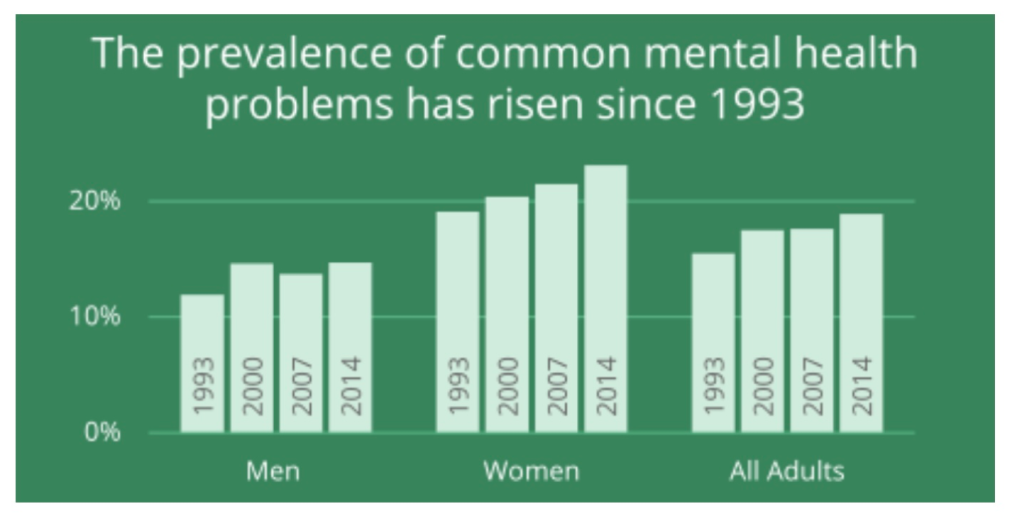

There is however evidence that in certain respects psychological suffering is on the increase.

As far as the prevalence CMH problems is concerned, government statistics report that there has been an overall increase in the prevalence of common MH problems between 1993 and 2014.

It’s not clear though how far this chart illustrates growth in actual distress, and growth in consciousness around valuing of the awareness of distress.

There certainly seems to be an increase in MH problems among young people, girls and young women in particular.

The number of A&E attendances by young people aged 18 or under with a recorded diagnosis of a psychiatric condition more than tripled between 2010 and 2018-19.

7% of children have attempted suicide by the age of 17. 72% of those in suicide counselling with NSPCC are girls.

26% of young women experience a common mental health problem, such as anxiety or depression – almost three times more than young men.

Suicide is the single biggest killer of men under the age of 45. And a marked gender split remains. For UK women, the rate is a third of men’s: 4.9 suicides per 100,000.

There is also some evidence that the number of people suffering Severe Mental Illness (SMI) is on the increase.

There is another way of looking for the meaning of the MH crisis: the social determinants of people’s distress and suffering

Let’s start with an understanding that life itself is difficult and stressful, that we are all physically, emotionally and spiritually vulnerable creatures what ever else, some more so than others at different times and in different places, and we need each other’s empathy, understanding and practical support to get by.

But this is not the way our society is organised. On the contrary, we are living in a society that generates misery, anxiety, loneliness and depression.

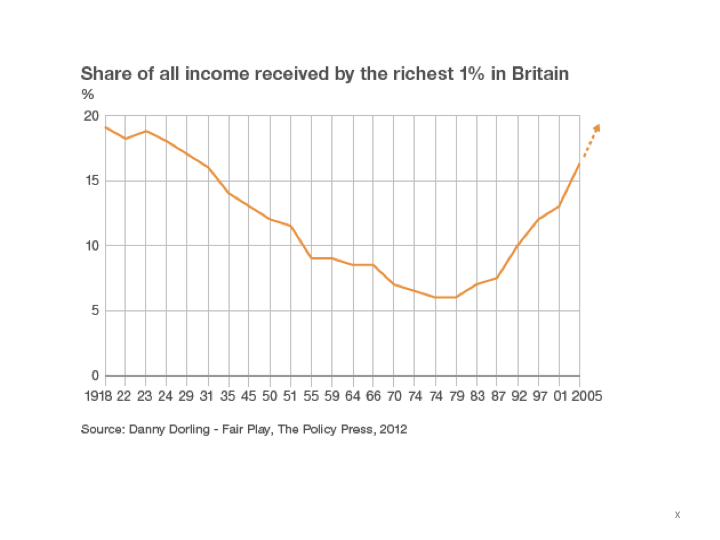

As a socialist, I’d argue that the MH crisis is a crisis of capitalism, in other words it is a systemic crisis around the power relations of class, race and gender, a crisis of alienation through the transactional worlds of markets and money, a crisis of exploitation and the extraction of resources, a crisis of greed and inequality, a crisis of the undermining of community and of social relationship generally.

Just as modern capitalism is driving us towards breakdown in our relationship with the natural environment, it is driving us towards breakdown in our relationship with our emotional and psychological environments, our bodies and each other.

It is generally acknowledged by most academics, policy makers as well as activists that the social conditions of people’s lives have a critical causal impact on the levels of stress, anxiety and depression they experience. More importantly, it is just plain common sense to most of us.

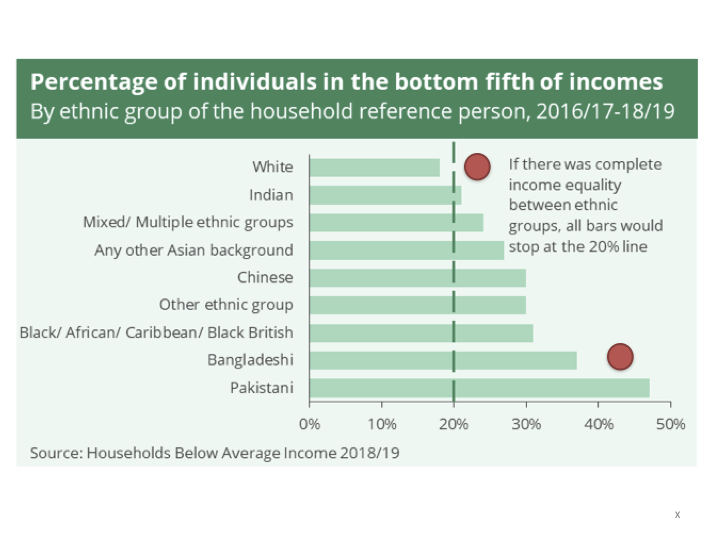

One of the most recent and extensive examinations of the social determinants of mental health in the UK is the Marmot review 2020. Michael Marmot compares the state of UK society ten years after his previous report of the social iniquities of health. He reports on the major inequalities in socio-economic conditions contributing to disparities in physical and psychological health in the UK. The catalogue of social determinants includes inequalities of income and wealth, poverty, household debt, lack of decent housing, welfare cuts, food and fuel insecurity, lack of social mobility and equal opportunity, racial discrimination, sex and gender discrimination, adverse and abusive working conditions, childhood poverty and adverse experience.

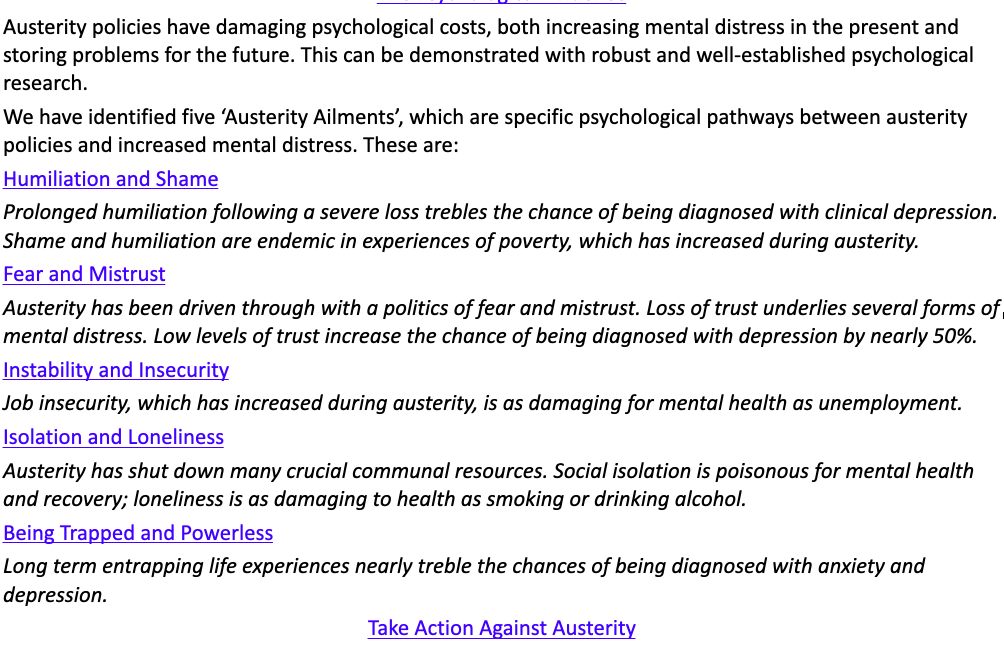

A few years ago, Psychologists for Social Change spelt out the emotional impact of austerity polices on ordinary people like this:

And more recently, Jack Munro has described the link between poverty and psychological distress with passion in the Guardian:

“The 14.5 million people living in poverty in the UK today are ticking time bombs of increased toxic stress, post-traumatic stress disorder, CPTSD, cognitive difficulties, depression, gum disease, chronic fatigue, osteoporosis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arterial disease, mental illness, diabetes, hypertension, inflammation, autoimmune disorders, suicidal ideation and suicide.”

What would follow from all this for any government or policy maker really concerned about the MH of the country is that addressing socio-economic iniquities via social policies like a basic living income and adequate housing for all, equality of opportunity through education, a proper social security safety net, redistribution of wealth and income via progressive taxation etc etc – these are the essential changes we need to become a more secure, confident, emotionally open and relating society.

In fact, we have seen the opposite – since the crash government policies have prioritised wealth accumulation by a minority at the expense of the social, material and psychological well-being of the majority, culminating in the austerity policies introduced after 2010 which have utterly immiserated the most deprived areas of the country .

The reality of the government’s concern for the UK’s mental health crisis: managing the dysfunctional system of modern capitalism

In fact while we are ostensibly in the midst of a MH crisis, and governments have been raising the alarm and talking about more resources for MH services, more staff, more community MH, parity of esteem – the same governments have in fact been cutting MH services, cutting beds, imposing real pay cuts, and accumulating staff vacancies.

The total number of mental health nurses in NHS England is down by over 3,000 in real numbers since 2009. Between 2009 and 2020 there has been a 12% drop in the number of mental health nursing posts.

Anyone with severe and enduring MH issues looking for support in the community will know that resources, ongoing professional support, decent housing, a reliable relationship with a key/social worker/psychiatrist are just not available.

Both the climate and MH crises are symptoms of systemic breakdown in our society Both have the power to turn our world upside down. Both are being managed as if they are unfortunate but inevitable consequences of progress. Both are being approached by the political class with disingenuity and duplicity. It is increasingly clear that people with power and money do not actually care about the lives of ordinary people. Both require social and political transformation.

As far as common MH conditions are concerned, instead of responding to the growth of symptoms of distress and inability to cope as a signal of something dysfunctional in the way society and the political economy are organised, the problem has been defined and responded to as the dysfunction of the individual.

So, for many of the more establishment commentators on the social determinants of mental health, social factors may determine the conditions which are likely to promote MH problems, but the causes of each person’s symptoms lie in their individual predisposition to mental ill-health – bio-chemistry, negative cognition, negative behaviour.

The current state of denial of systemic crisis is demonstrated in the term – mental health crisis. Mental health is a misnomer. First, the emphasis on cognition implied by the term “mental” is deeply unsatisfactory in that psychological life is much more about the dynamics of emotional relationship, unconscious life, fantasy, dream, and embodied experience as anything mental or cognitive. Second, applying the medical model of health and ill health to psychological experience implies a norm of healthy psychological life, and the pathologising of so many everyday dimensions of the human condition – depression, anxiety etc. loneliness, sorrow. defensiveness, paranoia, euphoria, the multiplicity of the self – that might conflict with the one-dimensional narrative of normalcy within the frame of neoliberal values.

Put another way, the term mental health is also a POLITICAL misnomer. It is however the most generally acknowledged language of psychological life and suffering.

If unhappiness and emotional pain is an individual illness, it can be treated under the medical model through scientific investigation, evidence-based diagnosis and treatment plans with the goal of getting us back on the horse of normal, healthy life – or offering us an understanding that if we cannot, it is our individual insufficiencies and weaknesses that are at fault.

Lord Richard Layard, co-founder of the IAPT service and Tony Blair’s Happiness Tsar, helped set up Action for Happiness in 2010. The front page of its website used to picture its understanding of the causes of unhappiness like this:

It’s a telling image. 50% of our happiness or unhappiness is rooted in our individual genetic make-up, the social determinants of happiness account for only 10%, and 40% can be influenced by cognitive or behavioural action.

The IAPT service, informed (loosely no doubt) by this kind of “evidence-based finding” is an excellent example of an approach to mental health that confirms that there is a crisis, that the crisis is based in the unhealthy mentality of individuals, and that it can be diagnosed and fixed without changing the fundamental structure of society..

Since its roll out in 2008, the number of people referred to IAPT has grown to 1,700,000 in 2019-20. IAPT currently treats people for depression, anxiety, a dozen categories of physical, emotional and behavioural disability, psychosis, OCD, several phobias, Long Term Conditions like IBS, obesity, chronic fatigue, PTSD, and body dysmorphia. It has an official budget of $700 million this year.

Current estimates of the prevalence of CMH problems in England put the figure at 20-25% of the adult population who will each year experience a diagnosable condition. IAPT is required by the government and the NHSE to offer access to psychological therapies to a quarter of that prevalence in 2021-22, a total of about 1.5 million adults. It is also required to achieve a 50% recovery rate.

What is so telling is that by the standard of its own targets, it is a total failure. If we look at last year, though it had 1,700,000 people as referrals (over the 1.5 million target) only two thirds started a course of treatment, only a third completed, and only 16% of the original 1.7 million recovered. In areas like Manchester the picture is significantly worse. Only 7% of its original referrals recovered.

If only a third of people applying for access to IAPT therapy 40% of the 1.5 million target) actually complete a course of treatment, can we then claim that we have offered access to therapy to 1.5 million people? If only 16% of those applying for therapy end up being successfully treated by IAPT’s measure of success, can we really claim a 50% success rate. I don’t think so.

Despite all its claims to have transformed access to therapy on an unprecedented scale, IAPT is in reality a grossly ineffective and wasteful use of NHS resources. In fact, I think it would fair to say that its primary role is political rather than therapeutic, namely to manage on behalf of the state a severely dysfunctional and sick social system, and to disguise this unwholesome fact with a smokescreen of diagnosis and cheap behavioural “solutions”.

Campaigning with uACT

No government or political party in modern Britain has so far prioritised the basic material, relational and emotional needs of the people over the interests of capital. Social and economic policies have therefore consistently carried a cost of harm to the psychological welfare of the many in the interests of the few. Unless and until this changes, government mental health policies are likely to be taken up with attempting to mitigate the damage it is itself inflicting on the society it purports to serve.

At the heart of the uACT campaign is the understanding that the fundamental problems facing us as a society, and perhaps particularly as therapists, is the fact that we are becoming an increasingly transactional, managed society. Human relationships are being stripped out of our public lives at a rate of knots. The inequalities and suffering in our society are being treated as problems to be addressed piecemeal by technical and administrative strategies that reduce us as human being to data and data management.

In the world of counselling and psychotherapy, IAPT and the reforms currently being introduced in the NHS are at the cutting edge of building a society in which open ended mutually respectful relationships between people are being reduced to behavioural and financial transactions.

UACT is a campaign for the promotion of universal access to open, democratic and mutually respectful relationships within counselling and psychotherapy, and in a wider sense it’s also a campaign for community and relationship at the centre of society and our politics as a whole.

The Anti*Capitalist Resistance Editorial Board may not always agree with all of the content we repost but feel it is important to give left voices a platform and develop a space for comradely debate and disagreement.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Event Video Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War