The Stars at Noon directed by Claire Denis is now out on general release and digital download. Denis builds up an atmosphere of sultry passion and menace in Pandemic-hit Nicaragua. The two main characters stumble from alcoholic daze to bruising encounter with the authorities and back again, making mistakes at the level of business espionage and in personal choices, clinging to each other and then eventually are sucked into betrayal.

There are troops on the streets of Managua, the capital, but it is not clear whether this, and the mainly empty streets, are the result of lockdown or military rule. There is endemic corruption, but it is unclear how much this is to do with the government itself or a function of a run-in with Costa Rica or the CIA. Both of these threats are mentioned in the course of the film, as is the oil company that the luckless and possibly clueless Englishman has crossed.

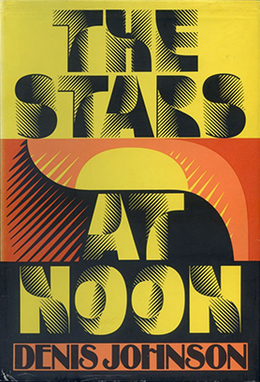

The Book

Claire Denis adapted the film from a 1986 book by Denis Johnson, though there are some differences between the two, between book and film. Denis is fairly faithful to the atmosphere conjured up in Johnson’s sardonic noirish first person narrative. The story is told from the point of view of a woman who likes to think she is a journalist but who makes her living selling sex, and trading sex for resident status from policemen and low-level ministers.

While the film is ostensibly set in the near past, with postponed elections and suggestions of vote-rigging prompting cynical commentary on the political process, Johnson’s book is set in 1984, and reference in the book to postponed and fiddled elections is pretty ripe – a reflection more of Johnson’s own miserable alcohol and drug fuelled time in Central America than of reality. The book, in fact, while well-paced, building tension as the couple head south towards the Costa Rican border, is laced with heavy-handed irony.

We are told several times, for example, that living in Nicaragua in 1984 is ‘Orwellian’, and one of the main characters – I won’t tell you which to save you from unnecessary plot-spoilers – reflects on a moment of betrayal with a deliberate reference to the betrayal of Julia in Orwell’s own novel. Perhaps we could forgive Denis Johnson and even Claire Denis, and read the book as a sad prediction of how things eventually unrolled in Nicaragua after 1984, but this does not do justice to the hopes for the Sandinista revolution, and the experience of those who visited the country in solidarity with the revolution back in ‘84.

The Revolution

For a critical trustworthy account of what was going on in Nicaragua at the time you could not do better than turn to Dan La Botz’s 2016 What Went Wrong? The Nicaraguan Revolution, a book that has prompted comradely discussion about the political analysis he gives us. La Botz likes to say that Nicaragua was about the size of Wisconsin or New York State, though that might mislead readers who don’t know how large these places actually are; Nicaragua stretches from the Atlantic to Pacific Oceans, and is actually larger than England.

La Botz takes us from the history of conquistador mass murder to US-American freebooting back in the day – in which Nicaragua suffered a staggeringly high number of deaths from invasion and then ill-fated business ventures –and then to the years of the Somoza family dictatorship, which lasted until 1979. The Somozas controlled not only the state apparatus but also the bulk of industrial and commercial concerns, all run with the active blessing of successive US administrations. This, La Botz shows us, also put the Somoza family, which was based in Managua, in conflict with both conservative and liberal ruling families based in León and Granada.

The FSLN, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, was founded in 1962 by members and allies of the Nicaraguan local communist party, and, by 1979, was itself composed of three factions, of which the ‘Terceristas’ led by Daniel Ortega balancing between left and right in the Frente was the most canny and well-placed. Augusto Sandino, who the FSLN was named after, was actually a good choice for those who wanted to build a radical origin myth for the struggle against the Somoza family.

Sandino, assassinated in 1934, was ‘radical’ and would even claim to be ‘socialist’, though, as La Botz points out, that term could mean pretty well anything at the time. Sandino was definitely not ‘communist’, and said so publicly a number of times, and instead, as well as being a yoga-practising vegetarian, was a member of a weird group called the Magnetic-Spiritual School of the Universal Commune.

The main problem, though, was that the FSLN replicated the top-down political structures they were combating, and they took as their model the Stalinised Cuban regime. Whatever was actually radical about Cuba, and there was still plenty even in those crucial years of struggle, was lost in the translation of the apparatus in Havana to the internal organisation of the FSLN.

1979 was a dramatic breakthrough, but there was no attempt to inspire grassroots democracy or accountability of either the FSLN after victory or the state apparatus. In classic Stalinist popular front vein, Ortega cobbled together an alliance with ‘progressive’ business leaders – those who had been excluded from the Somoza dynasty –and they bided their time. Eventually worn down by the relentless ‘contra’ attacks – something that also made full democratic functioning very difficult in 1984 – and by impending collapse of the Soviet Union, Ortega did a deal with the IMF, and paved the way for the return of the right under Violeta Chamorro in free elections held in 1990.

Ortega swung into pole position to take back the Presidency in 2006, eventually outflanking the government from the right and doing a deal with the virulently anti-communist Archbishop of Managua Miguel Obando y Bravo. Attacks on the opposition by Ortega included antisemitic slurs. The deal with the Catholic church was made over the bodies of Nicaraguan women, with the introduction of a ban on abortion; the deal blessed in Ortega’s full-pomp wedding in the cathedral with Rosario Murillo, to whom he was already married.

Away went the black and red Sandinista regalia, and in its place came the image of the happy couple and good family, with Murillo effectively functioning as unelected Vice-President before she was actually named as such. The Ortega children own most of the media. This is a new dynasty in the making. Membership of the FSLN mushroomed, but not on the basis of political mobilisation; instead tempted in by the chances of economic privileges.

La Botz notes that preferment or exclusion were the main carrots and sticks of the Ortega regime rather than outright dictatorship, though since his book was published things have taken a turn for the worse with more arrests and the slide into a police state condemned by the anti-stalinist non-campist left internationally.

The Film

Back to the film, which is heavy on image – of beauty amidst devastation – making the setting as important as the book, but a setting stripped of political coordinates; as you follow the characters from Managua to the border, you have as little sense of where exactly these people are as you do about the reasons they are in such a mess. The music by Tindersticks is haunting, and will carry you through the 135 sometimes puzzling minutes of the film.

As far as COVID is concerned, and something you won’t find out from the film either, the Nicaraguan government was either lucky or lying. There were indeed Cuban doctors there, as you see shuffling around the Managua Intercontinental Hotel. Nicaragua did not impose a lockdown, and carried on with sporting events until quite late on, eventually getting Sputnik V financed by the Russian Direct Investment Fund, and it reported very low deaths, among the lowest in Latin America.

Opposition groups have challenged these official figures, and the country is still putting big bets on tourism lifting the economy, still requiring a negative PCR test result for visitors. Rosario Murillo, still Vice-President, is, like her husband, still very religious, combining Catholicism with advice from fortune tellers. Maybe they have good news for her. You won’t learn much more about Nicaragua from the film than you will from the Sonic Youth track The Sprawl, which was inspired by the title and which includes quotes from the book in the lyrics.

Art (53) Book Review (121) Books (114) Capitalism (65) China (79) Climate Emergency (98) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) Economics (40) EcoSocialism (55) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (56) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (70) Gaza (60) Imperialism (98) Israel (123) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (52) Labour Party (111) Long Read (42) Marxism (48) Palestine (169) pandemic (78) Protest (152) Russia (340) Solidarity (142) Statement (48) Trade Unionism (141) Ukraine (345) United States of America (132) War (368)

Latest Articles

- Solidarity with LA, we cannot let Trump and ICE winSusan Pashkoff reacts to events in Los Angeles

- Barcelona Primavera Sound and PalestineJoe reports on a festival that took place from 2-8 june in Barcelona that put Palestine solidarity front and centre

- Critical minerals and genocide in the CongoWhat’s behind the sudden surge of interest in rare earth minerals. Phil Hearse investigates.

- York Pride“What a big celebration it was!” Liz Thompson reports back from her first experience of York Pride when her son and his family invited her over from Leeds, to enjoy this year’s celebration.

- Red Roots Collective Solidarity StatementThis statement from Red Roots Collective (a group of Iranian activists based in Manchester) is against the Zionist war on Iran and in solidarity with the people of Palestine.