“Next time is next time. Now is now.” (Hirayama)

A friend who is a specialist on Japanese culture met me before we went to see the film and said she was not that impressed with it—too submissive, too Zen-like acceptance of our world. Socialists, aiming to transform society, would likely react to the film this way, challenging the capitalist reality of inequality and ecological disaster.

After watching it, I am really torn between two reactions to the movie. Maybe that is a sign of a serious, engaging film. Is it superficial and neutral, and does it leave out the social processes behind the individual story of the near-perfect worker? Or does it make us reflect on how our 24/7 digitalized lives are cutting us off from valuing the moment, empathising with others, and seeing the beauty of our natural world? Let us look at the case for the prosecution and for the defence.

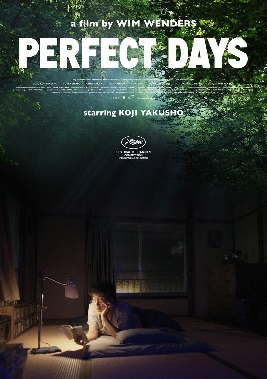

This is a two-hour film where nothing much happens. We follow the daily routine of an older toilet cleaner, Hirayama. He lives in a very modest house with few luxuries. We see him get up early each day with the noise of a neighbour doing her early morning cleaning. He washes, trims his moustache, dons his impeccable overalls, gathers up his old-style camera, wallet, and keys, and goes out to get in his official van. We remember all these details because, like in the film Groundhog Day, they are repeated a number of times in the film.

Unlike Groundhog Day, the main character is not trying to escape the routine but rather embraces and reveres it. There is hardly any dialogue until the end of the film, when there is a little more. The camera follows his meticulous cleaning of the public toilets. He has even developed his own equipment to improve the service he provides, such as a special mirror to check under the rims.

Although he is alone, we see him with his irritating young co-worker, whom he generously helps out, and with his niece. Rarely speaking, he smiles at people in the park, where he eats the same lunch every day. He rescues a young child from a locked toilet and delivers him to a very ungrateful mother. Later on, he meets his sister, and we find out how he is estranged from his family, who are reasonably well off. During his lunch break every day, he takes a picture of the tree canopy with its interplay of light and shadow. He always eats at the same couple of places. In one, he appears to have (or not?) some feelings for the woman. The film comes to an end after he meets her ex-husband, who is dying of cancer.

That is about it, and the closing scene is a long take on Hirayama’s face with Nina Simone singing Feeling Good. You can see why he won Best Actor at Cannes just with this scene, as he shows a beguiling joy in life, but in moments his expression suggests a poignant backstory of loss and pain. Just recounting what happens makes it sound like one of those tedious, overlong arthouse movies that people fall asleep in. I suppose this is Wenders’ art; he can show you a non-touristy Tokyo and get you to see things the way his main character does.

Architectural lines and spaces are beautiful if you see them from a certain angle. Repetition, which is part of the Zen-like submission of the main character, is portrayed as serene and comforting, an anchor against daily vicissitudes. The beauty of the everyday transforms with the addition of an uplifting soundtrack by Lou Reed, Patti Smith, the Kinks, the Animals, and Otis Redding.

The Christian Brothers at my Catholic secondary school educated me about monastic life. We were told how those men or women who entered closed contemplative orders found joy and fulfilment in the daily routine of work and prayer. St. Benedict’s Rule lays it out in great detail. Buddhist monks have a similar framework. For Hirayama, every moment is valued and savoured, and his work is a service to others, like the monks. He tries to be positive and empathetic towards everyone.

Wim Wenders, in his Variety magazine interview, put it like this:

The skill is very simple: for him, all people are equal. For him, there are no nobodies. In his own opinion, he is not a nobody either. So he recognises the ‘nobodies’ around him very acutely.

Repetition as such: if you live it as repetition, you become the victim of it. If you manage to live it in the moment, as if you’ve never done it before, it becomes a whole different thing. (…) And it becomes a beautiful, dignified job if you reinvent every day what you do and who you do this for. But most of all, you have to like the act of being of service.

Some films teach us to see carelessly; others show us how to see with a loving look.

Wim Wenders

Giving service and the beauty of everyday life

For people working to change society, we need to respect people who give service and value empathy with strangers. For eco-socialists, recognising and validating the beauty of nature in our everyday lives inspires us to want to preserve the natural world from capitalist destruction. Those endless photos of the light and shade in the trees taken by Hirayama express that feeling. He takes time to cultivate bonsai trees. You also cannot easily build a coalition for socialism with people who are cynical or always see the glass as half-empty. We embrace the optimism of someone like Hirayama.

James Cannon, the historic US revolutionary leader, reminded party members working in trade unions to win the respect of fellow workers by doing a good job. Showing competence and not letting the team down were important if you wanted to represent fellow workers. So doing the job right is not such a bad thing.

You could also see the film as a hymn to the importance and dignity of doing menial jobs; such work is essential, and we all need to value it. Re-valuing jobs and making remuneration more equal requires us to understand the common validity of all work, from brain surgeons to toilet cleaners.

There is often prejudice in our society for people who have chosen to be alone. We sometimes confuse being alone with cold loneliness. Society imposes the family model. Hirayama has consciously chosen this life. He does not want our pity. People can find fulfilment in a solitary, contemporary life.

Isn’t it all a bit sentimental, patronising, and pretentious?

Watching the film, you could tell that this guy is the perfect worker for the bosses. He does a near-perfect job. He keeps his head down and is totally isolated from any other toilet cleaners. Hirayama never complains about his salary and is happy to live simply. If every worker was like this, profits would be even higher.

Nowhere in the film do you see the reality of how many cleaners are treated harshly under capitalism. A recent French movie, Les Brillantes, about a group of night shift female office cleaners, gives you a totally different view of such work. A takeover meant the women had to travel much further to clean different offices. Pressure is applied for them to sign the new contracts, and supervisors attempt to divide and rule.

None of this is revealed in this Tokyo story. There are no managers working on speeding up the work or cutting jobs. In fact, this toilet cleaner seems to work with perfect autonomy, travelling in the van from home to work and back with no interference. Is real life really like this? Would the serenity of his daily existence be so easily maintained if he did not have this apparent autonomy?

Then there is this glorification of the analogue format—the cassettes and the camera—against the digital world that we see in the movie. Some reviewers see this as innately positive. Hirayama excludes himself from the digital world. Is that necessarily positive or progressive?

Yes, the respectful depiction of toilet cleaning as important and essential is fine, but in the film it does not go any further, and no links are even made to the huge salary disparity between so-called skilled and unskilled jobs, between mental and manual labour.

As one critic put it in the New Yorker review:

Perfect Days” comes off as Wenders’s exaltation of humble and uncomplaining submission—someone else’s, not his own.

Is it two hours well spent? On balance, I think it is well worth it. Even with the caveats we make in this review, it still plunges you into a world you might not have thought about much, and Yakusho certainly draws you magisterially into the humanity of the main character. Good films allow you to reflect and discuss different interpretations; they open, not close, conversations.

Art (52) Book Review (121) Books (114) Capitalism (65) China (79) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) Economics (39) EcoSocialism (55) Elections (82) Europe (44) Fascism (56) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (69) Gaza (59) Imperialism (97) Israel (119) Italy (45) Keir Starmer (52) Labour Party (110) Long Read (42) Marxism (47) Palestine (163) pandemic (78) Protest (149) Russia (334) Solidarity (133) Statement (48) Trade Unionism (134) Ukraine (339) United States of America (129) War (362)