“I did what I wanted to do. I am proud to have been part of the Republican Movement, and I hope that I have played my very small part in the success of the armed struggle.”

Rose Dugdale died a few weeks ago, in March. Until her final breath, she remained steadfast in her unwavering dedication to the Irish Republican cause and its armed resistance against British rule. She maintained that the Good Friday Agreement served as a testament to the effectiveness of the armed struggle, asserting that it compelled the adversary to come to the negotiating table.

The film focuses solely on the first 33 years of her life, leaving out her extensive and long-standing involvement with the IRA that spanned several decades. It focuses on a spectacular but unsuccessful heist of fine art paintings from an Irish country mansion. The narrative goes back and forth between the drama of the heist, her childhood and early development as a revolutionary, and the tension of the holdout as the gang negotiates the prisoner’s ransom for the paintings.

She was born into an upper-class family with a country house and residences in London. Her father was a millionaire underwriter at Lloyds of London. She had a private education and went on to finish school in Switzerland. In that era, it was customary for the daughters of aristocratic and wealthy families to participate in the London social season as debutantes, a rite of passage that included being formally presented to the Queen. Reluctantly, she went, in exchange for her parents agreeing to let her go to university. At Oxford, she was radicalised by the ferment of the 1968 revolutionary upsurge in France, Vietnam, and Prague. The rise of second-wave feminism also marked this period. The film features a scene depicting her and other women, dressed as men, staging a protest at the traditionally all-male Oxford Union, an institution where aspiring politicians sharpened their oratorical skills in preparation for the highest offices in the land.

Finishing university with academic success, she moved on to London, living in a squat and becoming an organiser in the Claimants Union. Her unwavering dedication to the cause and renunciation of her privileged background were exemplified by her decision to sell the apartment her parents had gifted her and donate the proceeds to those in need and to support radical initiatives.

Here, the film does not feel quite right in the eyes of anybody who actually lived through these events. Unless time has edited our memories and we really do look a bit stupid at times, the squat scenes look too formulaic, and the language is rather stereotyped and wooden. Also, as some comrades have already pointed out, nobody on the left in support of Irish unity used the term ‘Northern Ireland’ as the characters here do. The film compounds this mistake by having some of the IRA members use the same words. . Six counties was the accepted term.

In order to raise more funds, she organises a burglary of her family’s country mansion. This adventure is more Ealing comedy than anything else, as she and her boyfriend, Walter Heaton, are caught in the act of nicking the family silver. Her class, almost certainly meant she got off on a suspended sentence, whereas her friend was sent down for six years.

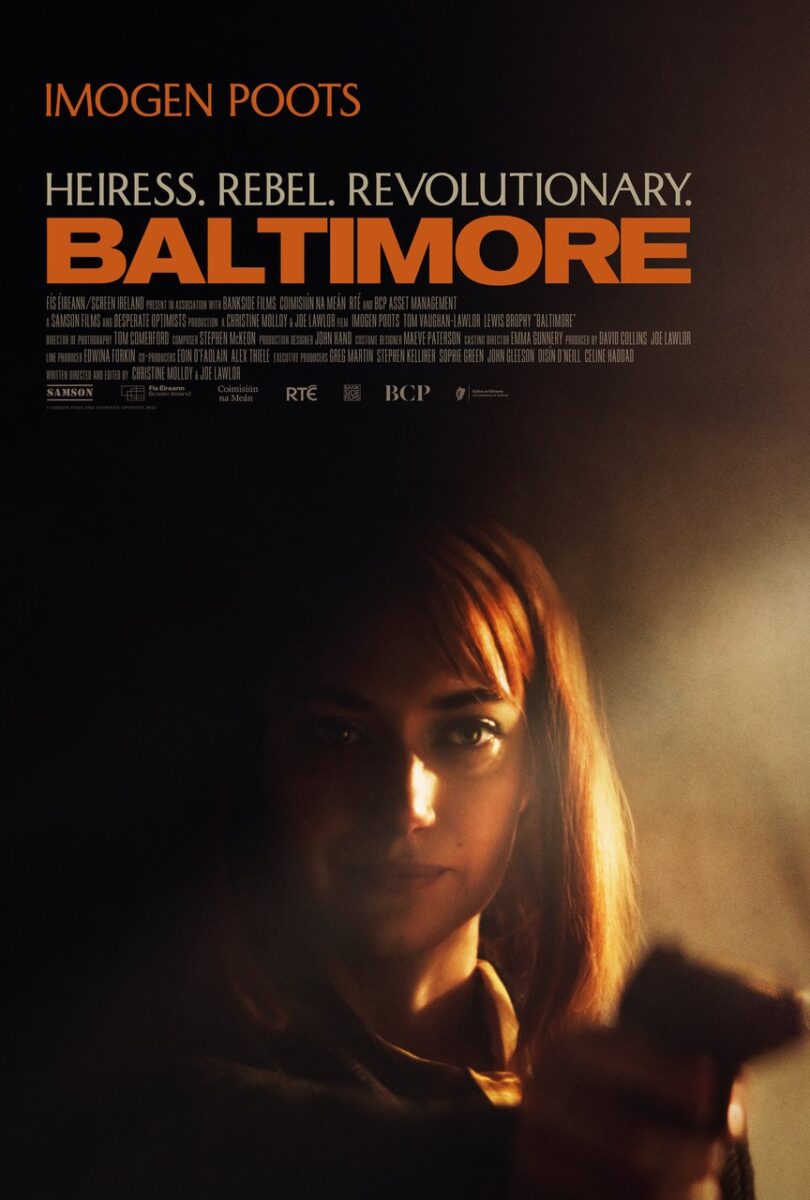

The film really is Rose’s story, and we see events through her eyes. Imogen Potts does a good job of showing her bravery and her doubts at particular moments. She leads the heist team with a cool hand, recognising that her younger male accomplice was a liability and taking over the holdout and negotiations entirely alone. The writers rather clumsily use incidents with foxes to express Rose’s sensitivity; she is upset when she is inducted into country fox hunting and then later hits and kills one in her car. It just seemed like a crude metaphor or symbol. The music is often overblown and intrusive too, getting in the way and distracting rather than enhancing the action or our feelings about it.

Whether intentionally or not, the film does reveal the political limitations of the armed struggle tactic. On the one hand, the IRA’s military defence of their community and its resistance against soldiers occupying their homeland had a logic, an effectiveness, and were based on mass support. On the other hand, bombing civilian targets was counterproductive. It fuelled sectarianism and eroded political support for its political objectives. The difficulty with a military wing is how to maintain its subordination to the political leadership and keep the organisation’s mass political resistance as its centre of gravity.

At the time, in the 1960s and 1970s, many militants showed the difference between reformism and revolution, mirrored crudely as the difference between armed struggle and conventional mass politics—being in parliament, mass trade union work, or public campaigns. Armed struggle became a strategy and not a tactic. This led to disasters in Latin America, resulting in the loss of thousands of revolutionary cadres. In Germany, we had the Baader Meinhoff groups and the Red Brigades in Italy. Those groups believed that spectacular actions, such as hitting high-profile individuals or bombing institutional targets, would somehow expose the reformists as repressive collaborators and jerk the anger of the masses onto their side. Again, it led to a weakening of the left and a strengthening of the very reformist forces they were fighting against.

Robbing fine art—worth tens of millions—was an action carried out in isolation from the mass base. By their very nature, such operations have to be secret. Also, as the film shows, the strategic objective was shaky since the prisoners for whom the paintings were to be exchanged were against destroying the paintings. At the same time, the museum director who Rose negotiated with was not even the person who could decide anything.

The film includes a quote from a representative of the Price sisters, stating that their struggle was aimed at creating a better world, and that they had no intention of destroying the beautiful creations and achievements of past generations. I think they are right about that. We build a socialist alternative, not by indiscriminately destroying everything connected to the old regime. Pol Pot and the liberation army did this in Cambodia when it proclaimed Year Zero. We know how that ended with a mass slaughter.

Actions by Just Stop Oil or Extinction Rebellion that threaten works of art are shortsighted in this respect. Museums can be the arena for protest, for example, against BP or Shell sponsorship, but progessives should not in any way be associated with vandalism of art that is the heritage of humanity.

Inevitably, as the film shows with the violence against the elderly art owners or potentially against the person who had recognised Rose, you end up dealing out the same collateral damage that our militarist rulers mete out in their wars every day.

A comprehensive biographical film about Dugdale would have been fascinating, considering her long-standing role as a crucial bombmaker for the IRA in the years following the art heist. At her trial she was defiant:

The British have an army of occupation in a small part of Ireland—but not for long! (…) Britain is a filthy enemy, and the Dublin government is guilty of treacherous collaboration with England.

Baltimore—in other countries it has a much better name, Rose’s War—is not a great film, but it is a fair enough insight into how somebody who was born in wealth was able to choose the side of the oppressed and to dedicate her life to their just struggle. It also raises the issue of the relationship between violence and political struggle.

Art (54) Book Review (127) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (45) EcoSocialism (60) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (62) Film (48) Film Review (68) France (72) Gaza (62) Imperialism (100) Israel (129) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (56) Labour Party (113) Long Read (42) Marxism (49) Marxist Theory (47) Palestine (181) pandemic (78) Protest (153) Russia (343) Solidarity (150) Statement (50) Trade Unionism (144) Ukraine (351) United States of America (136) War (370)

Please get your facts correct. Rose’s

Boyfriend was white.

I am getting fed up with people thinking I’am black

Edited to reflect and “her

blackboyfriend”@ WH: then you need to take up the fact with the filmakers that your protrayal in Rose’s War/Baltimore is erroneous. Portraying you as a Black man has obviously been included by them to illustrate the issue of post-Windrush immigrants’ experience i.e. that access to British justice depends on aspects that you are born into such as your parents’ class, their race and immigration status etc. i.e. your parent’s demographics that make you what you are and that you have no control over. This is to demonstrate the point that there is no equality of access to real British justice – it can simply be dependent on your background.