Alice Neel painted this first self-portrait just four years before she died. The curators put it on its own in the first room of the Barbican Art Gallery exhibition. It shows her radicalism. A woman artist proudly portrays her ageing body. The complete opposite of how male artists mostly painted women in an idealised way mainly for the male gaze. Sitting on her favourite chair, where she had painted so many people, she sits with her brush in her hand as both artist and sitter. Neel spent five years on this picture, and her flushed red cheeks represent the effort she put into it. Her face betrays both the wear and tear of her life’s struggles and a steely resilience. There is still a hint of diffidence—a raised eyebrow and a slightly quizzical look—as though she can hardly believe her recently achieved and very belated recognition as a leading American artist.

Her first solo exhibitions, in small galleries, began in the mid-1960s. It was only in 1974 that she had a major retrospective with 58 paintings at the prestigious Whitney Museum of American Art. In 1976, at the age of 76, she was invited to join the National Institute of Arts and Letters. At an Institute event, Neel recalls a discussion about the institute being too old. She raised her hand and said:

Blame it on yourself, not me…it just took you that long to know I as good.

In the last room of the show, you can see film from her investiture into the Institute at the end of the exhibition, along with scenes of her doing one of her later portraits. She comes across as feisty, funny, and a really social person—curious and interested in people of all classes. In her final years of national renown, she was invited onto national TV, lectured successfully, and films and books were written about her.

This is the first major exhibition in Britain, and it is another sign of how art by women is ‘being discovered’ and given a rightful place in the canon. Having more women curators also helps this positive change.

The paintings on display reflect the energy and diversity of her life. She went to Cuba in her twenties and lived with Carlos Enriquez, who was to become one of Cuba’s best-known artists. She loses her one-year-old child to illness. Her husband moves away and settles in Paris, taking their second daughter with him. Neel has a complete breakdown and attempts to take her life. Her art helps in her recovery—”it was the drawing that helped me to get well’.

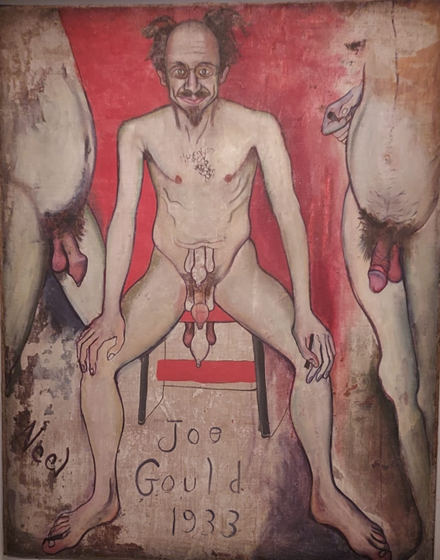

Neel then meets a sailor named Kenneth Doolittle, who becomes her partner. He recruits her to the Communist Party, and they move to Greenwich Village in New York, home to bohemians, gay activists, and radicals. She embraces the spirit of rebellion and imagination. This painting of Joe Gould, a well-known figure on the Village scene, was considered so scandalous, particularly for a woman painter, that it was not publicly exhibited for another 40 years. Neel jokes in the film that it reminded her of Russian Orthodox churches!

Life was never that relaxed for Neel; in 1934, in a fit of jealous rage, Doolittle burned over 300 of her works on paper and slashed around 60 of her paintings. The portrait of Gould is visibly singed.

After joining the party in 1935, Neel participated in anti-fascist demonstrations and supported workers who were defending their living standards during the Great Depression. Roosevelt’s Public Works of Art Project provided artists like Neel with a much-needed regular income. She got $26.88 a week and was expected to submit a painting measuring 23 by 30 inches every six weeks!

Here is a picture she painted of the police repression against the strikes at the National Biscuit Company.

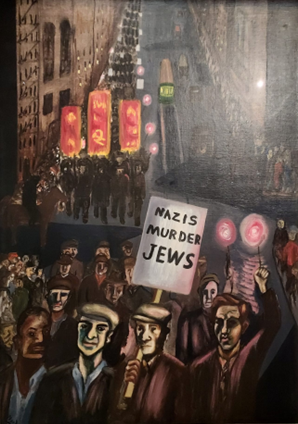

This is a picture helping the campaign against the rise of fascism:

After meeting a Puerto Rican nightclub singer, she moved into Spanish Harlem and painted its mostly Puerto Rican population. We have to remember that at that time most portraits were still mostly made of white, better-off people. As an artist, you are not going to make much money painting poor Puerto Rican families. She captures both the vitality of the people and the desperately poor conditions they were subject to. Women are prominent in her pictures.

Like Paula Rego she does not paint people in a photographic way. Her style is expressive realism. Here the faces and fingers seem over large and distorted but you are drawn into their gaze and a certain anguish and stoicism. The colours are bright but sombre. She explained:

One of the primary motives of my work was to reveal the inequalities and pressures as shown in the psychology of the people I painted.

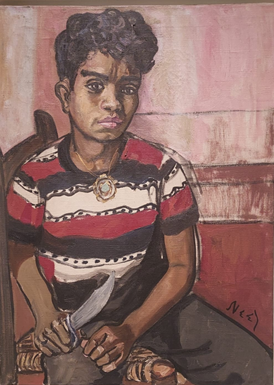

The young man shown here became very close to Neel. He used to hang around her flat and even wanted her to adopt him. He is shown here with a plastic knife. Unfortunately in later life he was convicted in 1974 of murder. True to her humanist solidarity she continued to exchange letters and greeting cards after he was incarcerated. This portrait also in my opinion shows how Neel got better as she got older. Her painting is more assured and more ‘worked’ if you compare it to the Lowry like, naïve depiction of people in the biscuit strike picture above. She herself admitted after working with a therapist that she became bolder and more confident about her work. The final pictures in the show reflect this:

Sadly Judy, the baby shown in this picture died shortly after this was painted. Carmen and her husband were exiles from Haiti’s Duvalier regime. Neel made many portraits of activists from the movement and the Communist Party.

Another reason why Neel did not receive as much recognition as she might have was due to the way the art world, particularly in the US in the 50s and 60s, had made a big shift into abstraction. Figurative work was seen as old hat compared to the drip paintings of Pollock or the colour swathes of Rothko. Even the CIA promoted the trend. It used the Congress for Cultural Freedom to fund art magazines, galleries, and exhibitions favouring the movement. It supposedly represented the abstract freedoms of expression claimed for American democracy. The CIA may have thought it posed less of a challenge to US capital. At the same time, the Soviet Union was at the other extreme, still promoting the virtues of socialist realism and, of course, repressing any art that criticised the bureaucratic regimes.

Neel herself stated:

I am not against abstraction. Do you know what I am against? Saying that Man himself has no importance.

Several recent big exhibitions have featured artists mainly working in the figurative genre; we reviewed the Yiadom-Boakye one a few weeks ago. Great art is great, whatever the media or style.

Alice Neel remained an activist to the end, including in her own field, protesting the exclusion of black and female artists from the mainstream art world. She became disillusioned with the Stalinist regimes because of their poverty, corruption, and repression. Hence, she eventually defined herself as an anarcho humanist.

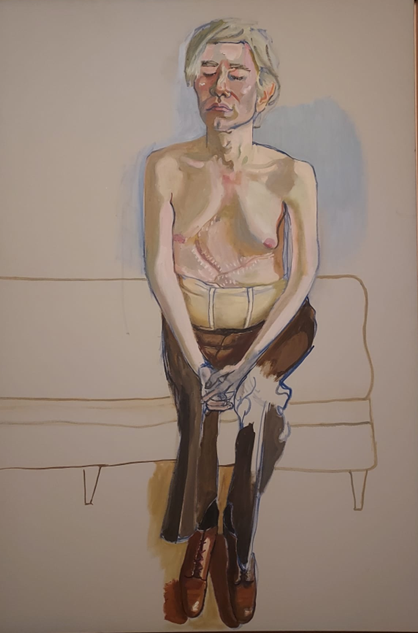

Let us finish with a remarkable portrait from this exhibition. She was friendly with Andy Warhol and somehow managed to persuade the notoriously private Warhol to have a portrait done showing the scars inflicted on him by the feminist Valerie Solanas in her assassination attempt:

As Keats said, beauty is truth, truth is beauty…I paint to reveal the struggle, tragedy and joy of life.

Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle – Thu 16 Feb—Sun 21 May 2023 at the Barbican

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War