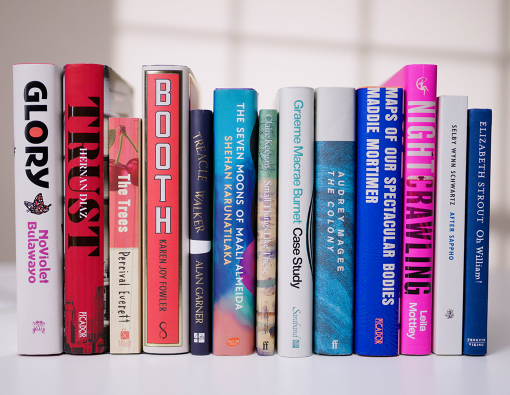

The Booker Prize process has seen some rocky times since it began in 1969, ranging from controversies over the composition of the panel to hissy fits by authors who imagine they should have won it. The scope of the entrants has expanded over the years, and that, along with a greater sensitivity to various dimensions of oppression, has given rise to some interesting long and short lists. This year’s crop gives us some good, interesting work: books that raise political questions from different contexts in an interesting way.

The prize is now supposed to be “international” in scope, though it still lists only books published in the English language. This year we have five books from the United States, two of which explicitly tackle racism, and one of which tries to take a long view of the history of racism in the US. There are two books from Ireland, one of which is concerned with colonisation. There are two books from further afield, one from Sri Lanka and one from Zimbabwe. There is a continental European book written by a US author, and there are three homegrown English books. So there are some openings and some restrictions.

The short list

This is my order of preference from the short list, and I’ll try to give you an idea what you are letting yourself in for without unnecessary plot spoilers, and I’ll try to be clear about what I liked and didn’t like. These may be idiosyncratic choices by the panel, of course, and you may well like the look of some of the books I was less keen on, but here goes.

Shehan Karunatilaka’s The Sevens Moons of Maali Almeida is a real book; long, well-structured, a compelling ghost-perspective on a time of many deaths in Sri Lanka. I’m not into supernatural stuff, but this works, having been written and rewritten for different audiences, now with some explanation of who the different local and international players are in Sri Lanka. It is, by turns, horrific and funny. At times it seems to be too balanced, throwing a plague on all parties, but it has its soul in the right place, raising questions about the role of a gay photojournalist in times of war and what hopes for redemption there might be for those who collude and those who resist.

Alan Garner’s Treacle Walker is a disconcerting and downright weird tale of someone. We don’t know their age or who they live with, though they seem young; when it is set; or where they live – though we guess it is somewhere up in the north of England. Garner is an old hand at mystic stuff written for young adults, and I’ve avoided his work up until now. At some point, characters bleed out of a comic the main character is reading, and there is a chase through mirrors out of this world and back into it again. It is cryptic but intriguing, and I really liked it, thinking about it a lot afterwards and wondering about what it was supposed to mean.

NoViolet Bulawayo’s Glory is set in Zimbabwe and is a surreal satire on the Mugabe regime that is configured as a cast of animals, with dogs as the “defenders” and the shock troops of the state. The word “tholukuthi” appears again and again scattered into the text as if at random. I found that very irritating. It means something like “and so we see” or “you find that,” and the phrase has become a trademark of the book. The corruption and viciousness of Mugabe are well captured, and no opportunity for scorn toward him or his successors is lost. We have a window into the history of anti-colonial struggle that eventually, and unsatisfyingly, in my opinion, tries to end more hopefully than Orwell’s Animal Farm, a book it deliberately alludes to more than once.

Percival Everett’s The Trees conjures up the world of benighted white hillbillies in the US, and they are made to seem all the more backward and ridiculous viewed from the perspective of some black cops brought in to solve some bizarre murders. The plot builds and the deaths accumulate. I liked this a lot, but I was puzzled over where it was going. This is about slavery and its aftermath, about a society haunted by its past, and about the failure to acknowledge and resolve racist trauma. Then, perhaps predictably, there is no resolution at all. Unkindly, perhaps, I felt that the author had a great idea and started writing, but then didn’t know how to click things into place.

Elizabeth Strout’s Oh William is based in the US, musing on the nature of character and relationships and eventually successfully drawing us into the little lives it describes. It is also often annoyingly and too-cutely written from the perspective of someone who is barely aware of what they are tangled in, written so well that one suspects that the writer herself is as naïve as the first-person viewpoint character they inhabit. None of the characters are really likeable, and there is a quasi-reflexive aspect to the book that is also annoying, but finally it works out, with threads surprisingly tied together.

Claire Keegan’s Small Things like These is a very slight novella. It’s not bad, but it’s too brief. It’s set in Ireland in the aftermath of the Magdalen laundries scandal, with an afterword about the thousands of young, pregnant, unmarried women confined and exploited by nuns. The writing is fluid, and – like Foster, which was made into a film as The Quiet Girl – it homes in on family life, in this case contrasting that with what is going on behind the convent walls. It sets the scene well but does not tie everything together, leaving us wondering what all of this means for the characters and the society that allowed it to happen.

The long list

Some of these lower down in the top thirteen are very good, and I would bump some of them up into the short list, while some of them are so-so. For the moment, let’s just take these seven that did not make it into the short list. Again, roughly in order of preference, here they are.

Selby Wynn Schwartz’s After Sappho patches together in a really neat way the queer lives of a network of women, – mainly literary types and mostly very rich – who disturb given categories of gender and sexuality from the middle of the nineteenth century to the 1930s. Many of them idealise ancient Greece, and ‘Sappho’ here is a potent signifier, exciting and inspiring them to live way beyond what they are told they should be. This is fiction and history, beautifully written and exhaustively researched, with a detailed account after the end of the book telling us what was adapted from what.

Maddie Mortimer’s Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies is a weirdly formatted book, and that’s something that disrupts the text – words are compressed, split, and wound around each other, and images complement the narrative. This makes it difficult to read on an e-book, and I converted it into simple text to read. The typographic image work is actually unnecessary, and that makes it feel overworked. But this debut novel is a surprisingly engaging and moving story of a family ravaged in different ways by cancer, told in fragments; the family fragments, and we watch them fall apart.

Graeme Macrae Burnet’s Case Study is, at times, very funny, crafted as a kind of elaborate spoof of the life of a radical psychiatrist – it’s clearly based on R. D. Laing, with that character appearing at other points to give some Zelig-style realism to the book. It rattles along through the voice of a relative of a patient out to outwit the shrink, revealing something weird about herself in the process. At some farcical moments, I pictured it as a song-spattered Dennis Potter TV series. There is nicely observed stuff about people pretending to be clients of therapy, as well as “untherapists” critical of their own institution and unwittingly getting drawn into what they think they are setting themselves against. It’s a good, long joke.

Leila Mottley’s Nightcrawling is the painful journey of a young black woman in Oakland. This debut novel just about escapes cynical charges that this is poverty-porn, and it hits some predictable buttons around the contradictions of sex-work and the intersection of racism and sexism among the exploited and oppressed. It feels at times like different kinds of sexual lifestyles are pasted in, playing to an audience. There is good stuff here clearly gleaned from creative writing class, with lows and highs, moments of desperation and then heart-warming bonding, and some legal tension and police violence. Written from the heart, but in a formulaic manner.

Audrey Magee’s The Colony is set on a remote Irish island in the 1970s, and the intrusion of an English painter – symbolic violence – is interleaved with a sequence of sectarian killings in the North. There are some clunky explanatory facts about language and colonisation inserted through the research writing of a French visitor who, for his own complicated reasons, wants to save the language. Despite some nicely observed scenes, the real menace and violence seem always to be located on the side of the Irish, and so some kind of journalistic “balance” ends up betraying whatever positive critical points that are being made.

Hernan Diaz’s Trust is structured around the conceit of “perspective,” with four different books in this book giving different viewpoints on the economic success of a US businessman, centred on the 1929 Wall Street Crash, from which he benefits. There are more red herrings than solutions, and what is revealed in the fourth book – and that, and this is a heavy clue, is about the Wife – is not the most interesting answer to the most pressing questions that are raised and forgotten as we go through the thing. The book shifts attention from who labours to create wealth to who is creative enough to calculate and invest wisely.

Karen Joy Fowler’s Booth is a rather tiresomely padded-out family story about the life and crimes of the guy who killed Abraham Lincoln in a theatre. It is a mythic narrative of interest, maybe, to US-Americans, and I remember seeing images of John Wilkes Booth pop up in DC comics stories and puzzling as a kid about what was going on. It is too long, and, infuriatingly, much of the life and family are fabricated. You won’t learn much, except that the good guy in the story, Lincoln, was himself a dodgy character who hedged his bets on whether or not to actually end slavery, so I didn’t care so much when he meets his maker at Booth’s hands.

The top three

The books are pitched in very different ways to different readers, and perhaps it is stupid to rank them. Different styles make for real difficulty in imposing criteria. I have two criteria here that clash against each other. There needs to be a political sensitivity that makes me feel that I’m immersing myself in something of the real world and getting a different, progressive, vantage point on it; there should be critique. And there needs to be an enjoyable flow so that I feel that I am finding a way out of this world, stepping out into a quite different landscape, of the world and characters; there should be escape.

So, bearing that in mind, if I had to choose, I would select the following as the top three from these thirteen listed books: First place went to Shehan Karunatilaka’s The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida (which beautifully and horrifically combines escape with critique), so I agree with the final Booker panel verdict. Then, second, Selby Wynn Schwartz’s After Sappho (for progressive historical critique in absorbing vignettes). Then, third, Maddie Mortimer’s Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies (for taking us into some surreal places to examine our mortality). In different ways, these works of “fiction” are also, as all good fiction should be, windows back onto the real world.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Protest Review Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women