I saw Richard Seymour introduce the key ideas from his book Disaster Nationalism at an ecosocialist summer camp in Ireland, just as news of a far-right uprising gripping the UK in early August was making headlines. Earlier that day, fascists had attempted to burn down a hotel housing asylum seekers in Rotherham, an act of mass murder driven by hatred and fury—a hatred of the ‘small boat people’ so visceral that it led them to attempt to kill.

Alongside this, the news from Israel painted a similar picture of escalating violence. Amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza, there was near civil war in the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF), with soldiers and far-right politicians resisting the arrest of soldiers accused of rape and sexual assault, arguing that if the victims were not Jewish, then it didn’t count. It is clear, Seymour argues, that when it comes to violence used to enforce a particular ethno-nationalism, the disaster is already upon us.

The Rise of Fascism and the Politics of Resentment

Seymour’s latest book offers a timely and insightful analysis of the global rise of the far right. He describes his approach as reading “incipient fascism as political dreamwork” (p. 201), exploring the relationship between economics, politics, society, and psychology. Drawing on thinkers such as Freud, Arendt, Billig, Mann, as well as figures like Donald Trump and Steve Bannon, Seymour builds a rich narrative. Much like in his previous work, The Twittering Machine, one of the most insightful books on the (d)evolution of social media—what Seymour terms the “social industry”—his writing provides a complex and layered engagement with these issues.

Seymour highlights the far right’s fixation on disaster and crisis. In a world rife with real crises—caused by a capitalism that destroys the planet and pillages communities—the far right concocts its own imaginary crises. They deny climate change but fear the World Economic Forum’s supposed plan to replace white people. In the UK, they rage against so-called two-tier policing, ignoring the well-documented racial bias in law enforcement against Black people. For these groups, permanent victimhood is key: they claim that white men are the ones being eradicated, oppressed by the left and people of colour who they argue hold all the power.

“They deny the reality of climate change but believe the World Economic Forum wants to replace all white people.”

Seymour makes it clear that the politics of resentment plays a central role in this dynamic. Yet, he argues, resentment itself is not inherently negative. It is a normal human emotion that can be channelled by both the left and the right, by socialists or fascists, depending on the target of the resentment and the proposed solutions. Disaster nationalism, in Seymour’s view, emerges from a perceived crisis within the dominant group, as their relative superiority—once sustained by national unity and privilege—is eroded. Formal legal equality, the entry of women and Black people into the workforce, and the defiance of traditional gender categories by trans people become threats. As Seymour notes, “The apocalyptic threat, from this point of view, is not plague, wildfire or ecological catastrophe. It is the liquidation of social distinction” (p. 18).

Fascism’s Violent Aesthetics and the Path to Authoritarianism

Seymour tracks the far right’s growing attacks on Critical Race Theory, ‘Gender Ideology’, and ‘Cultural Marxism’—the latter now a fascist trope openly embraced by some Tory MPs. These conspiratorial fears are deeply embedded in the belief that these ideas undermine tradition, threaten established social hierarchies, and challenge the status quo. During periods of austerity, when the state withdraws as a social safety net, these fears take on tangible form. In such times, the far right thrives by casting marginalised groups as the enemy. As Seymour argues, disaster capitalism is not yet fascism, but it paves the way for it, much like John the Baptist heralding an apocalyptic messiah.

“When the state as social cohesive is rolled back and brutal neoliberalism renders us all competitors, the far right finds its opening.”

A key aspect of Seymour’s analysis is his focus on the psychological underpinnings of fascism. Fascist movements are not built on rational discourse or reasoned debate. Instead, they thrive on a complex yet simplistic web of conspiracy theories rooted in persecution and the perceived loss of privilege. Seymour examines India as a case study, pointing to how Narendra Modi’s rise was fuelled by pogroms against Muslims in Gujarat, which helped garner Hindu support. The “Gujarat model” expanded the private sector, privileging the chosen few while sacrificing democracy for an ethno-nationalist vision.

The psychological nature of fascism is essential to understanding its irrationality. The far right’s belief in a zero-sum game—whether it’s incels feeling entitled to sex or nationalists fearing refugees will take their jobs—leads to a violent, authoritarian mindset. Seymour critiques the liberal response to fascism, noting that appeals to rational self-interest or the economy often fall short. The far right, he argues, understands the power of passion and emotion far more effectively than the liberal centre.

“Fascists live in a world of imaginary crises, where Black people and the left are in total control and white men are losing out.”

Seymour’s critique extends to the left as well, cautioning against a retreat into defending the status quo of liberal democracy and capitalism as if they were inherently good or natural systems simply under external threat from fascism. He urges the left to move beyond this framework and build a mass movement capable of offering a socialist alternative.

Seymour’s book is a compelling and necessary read for anyone seeking to understand the ideological and psychological landscape of today’s far right. It is a reminder that while fascism may not yet be in its full 1930s form, the conditions for its resurgence are present. To fight it, we must offer a viable alternative—one grounded in solidarity, empathy, and social justice.

“Seymour challenges the left to build a mass movement that offers a socialist alternative to disaster nationalism.”

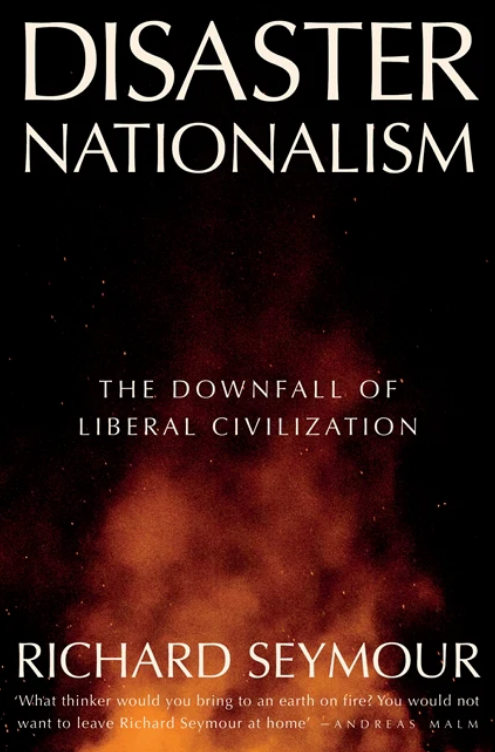

Disaster Nationalism: The Downfall of Liberal Civilisation by Richard Seymour can be ordered from Verso Books.

Art (54) Book Review (127) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (46) EcoSocialism (60) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (62) Film (48) Film Review (68) France (72) Gaza (62) Imperialism (101) Israel (129) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (56) Labour Party (113) Long Read (42) Marxism (49) Marxist Theory (47) Palestine (182) pandemic (78) Protest (153) Russia (343) Solidarity (150) Statement (50) Trade Unionism (144) Ukraine (351) United States of America (139) War (370)

Although of course relating to a different epoch, Wilhelm Reich’s ‘Mass psychology of fascism’ which explored the irrational resentments fuelling the members of the Nazi party has explored this ground before, as I recall (I read it 50 years ago). I’ve been raising the catastrophic consequences of not challenging them for a long time now, chiefly aimed at the suicidal disinterest of the LGBTQ+ communities. Fortunately, we don’t need the creation of a revolutionary party to beat them, just a little understanding of history…. oops, now that does cause a problem!