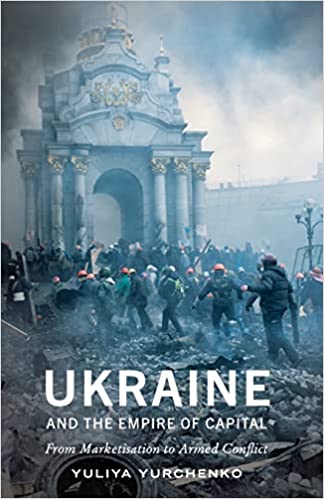

Spectre‘s Ashley Smith talked to Yuliya Yurchenko, author of Ukraine and the Empire of Capital: From Marketization to Armed Conflict (Pluto, 2018).

She is a Lecturer in International Business and Researcher at the Public Services International Research Unit, the Centre for Business Network Analysis, and the Political Research Centre at the University of Greenwich.

What are conditions like for people in Ukraine now amidst this war? What is the state of the military and civilian resistance to Russia’s invasion?

First of all, it’s really good to chat with you and tell the story of this war and resistance from a Ukrainian and leftwing point of view. I think everyone knows that Russia’s shelling has severely damaged whole cities, especially Mariupol, and killed untold numbers of people. Its troops and missile attacks have driven huge numbers of refugees out of the country and internally displaced even more people. Nobody knows the exact numbers.

Millions of refugees have fled to the surrounding countries and have been welcomed and given shelter and aid. At the same time, there have been instances of nonwhite migrants and refugees who have been blocked or sent to the back to the line. That has created some ugly clashes at the border.

I’m currently in Vinnytsia, roughly halfway between Kyiv and Lviv. It is considered one of Ukraine’s quieter cities. We have been struck by Russian missiles but not as frequently as other places. We have lots of internally displaced people who’ve fled here and found housing in schools, hotels, rented flats, and people’s homes. Networks of volunteers are providing them with food, clothing, and medication.

Since martial law was declared and medical supplies requisitioned for the troops, access to medicine is an acute problem. There are real difficulties getting prescriptions for insulin and blood thickening medications when people can’t see their family doctors and when supplies are low.

So, people who are internally displaced face acute health issues, even as volunteers help them. We will only know the extent of the harm the war has caused after it’s over. But people in mass numbers are paying an enormous price in life, health, and especially mental health.

Nevertheless, the resistance is massive. People have volunteered to serve in the military in huge numbers, more than in fact the military could accommodate. Those who didn’t have any previous military training were turned away, for now.

So, there are large reserves of people willing to join the military resistance, who were trained for fighting under the old Soviet system. Russia certainly cannot boast that. It does not have the political confidence to even call up reserves, because Russians have no convincing reason to fight, save some scarcely credible imperial myths.

For Ukrainians it’s an existential fight. Our country’s identity, territorial boundaries, and our very existence is under attack right now. So, the nationwide solidarity and mobilization in defense of the country has been great despite Russia’s overwhelming military advantage.

People are not giving up, despite the inevitably dehumanizing impact of the war, the sexual violence, and the demoralizing images, videos, and stories of the destruction in whole sections of the country. We are turning back the Russian invasion. It’s an all-out popular resistance that makes you feel very proud.

Few people expected this level of military and civilian resistance, including those who are most optimistic and patriotic in Ukraine. It also surprised the Western powers, who, I think, downplayed the threat of the Russian invasion and then thought that Ukraine would quickly capitulate. They thought it would be ugly but then be over in a couple of weeks.

Putin thought that too. So, the resistance has shocked the world. But it really should not have surprised everyone. Russia has triggered a resistance that is deeply rooted in a centuries-old fight of Ukrainians against Russian imperialism.

One thing that has been noticeable is the resistance among Russian-speaking areas of Ukraine. As we know, Russia has tried to exploit divisions between Ukrainian and Russian speakers in the country since the Euro-Maidan Uprising in late 2013. They seized Crimea and supported the so-called People’s Republics in Luhansk and Donetsk. What, in the predominantly Russian-speaking areas, does the resistance look like?

The resistance in Russian speaking areas like Mariupol has been inspiring. It has exploded the myth Putin propagated that he was liberating Russian speakers from fascist oppression. No one can believe that anymore.

At the same time, we need to understand where the division between Ukrainian and Russian speakers came from. They were manufactured in public consciousness since the 2004 presidential campaign and became solidified after the Maidan uprising in 2013-4. Maidan was a popular uprising not so much about joining the European Union, but rather opposing the oligarchs who control the country, the government’s brutality against protesters, and frustration with decades of lawlessness and corruption.

In that uprising, the far right, which was only a small part of the protest, played an outsized role organizationally. Pro-Russian oligarchs’ media commentators, not to mention the Russian state, played them up on TV, depicting Ukraine as overrun by fascists. This is not to deny the far right in Ukraine or its inherent threat, but just to say that it was exaggerated for political reasons by Russia and its allies – reasons they used to justify their seizure of Crimea and their backing of Russian separatists in Luhansk and Donetsk, many of whose leaders were planted there by Russia.

The popular reactions in Crimea and the so-called Peoples’ Republics were complex. We do not have an accurate and objective sense of what people thought. But it’s clear that many were afraid of infringement on their linguistic rights, but at the same time, many wanted to stay part of Ukraine.

It was a very complex picture that even divided families. Many also worried that they had no future in the country because of socioeconomic deprivation that either regime may bring. Sociological data reveals a complex picture beyond marginal errors or bias.

The military conflict between the Ukrainian government and its right wing paramilitaries Donbas exacerbated these divisions. It caused all sorts of atrocities on both sides. People fled the area, many into Ukraine and some into Russia.

As a result, the composition of Crimea and the so-called Republics have dramatically changed. But that doesn’t mean that everybody in in those territories are desperate to be part of Russia. We know that there is a lot of resistance in those areas to the Russian invasion.

In Crimea, the Tartar population, which was oppressed under the Tsar and then by Stalin, has resisted the Russian state’s repression. There are also serious problems in the so-called Republics that have led to deep alienation from the separatists that control them. There has been deindustrialization and the closing of some mines. As a result, the unions have raised complaints against the separatist statelets and have suffered human rights violations and repression.

In reality, those so-called People’s Republics are neither the people’s nor republics. They’re now under semi-dictatorial control and beholden to the Russian state. And Putin does not even trust their loyalty and reliability! So, in the buildup to the invasion, Russia started issuing orders to the separatist functionaries in these Republics to prepare to mobilize for the coming assault. Not everybody was thrilled about that, not even the functionaries. To enforce their loyalty, Moscow took their families to Russia – essentially as hostages to blackmail them into obedience.

While Russia does have adherents in the separatist republics, there is a disapproval and some outright opposition to the war. That’s true even in Crimea, where despite broader support for Russia, there is also dissent and opposition.

Let’s take a step back from these dynamics to explore the underlying causes of the war. Why is it inaccurate to reduce the war to a straightforward inter-imperialist conflict between the US/NATO and Russia? How does this ignore the struggle for national liberation?

Reducing this war to conflict between the West and Russia overlooks Ukraine and treats it as a mere pawn between powers. That analysis denies Ukrainians our subjectivity and our agency in the conflict. It also suppresses discussion of our right to self-determination and our fight for national liberation.

Of course, there is an inter-imperialist dimension to all of this. That’s obvious. But there is also a national dimension to it that must be recognized. And to recognize it, you have to put on your decolonial thinking cap.

You have to draw on all the lessons learned from national liberation struggles in Africa and elsewhere. Even in those cases where competing powers were involved, there was also the struggle for national liberation of oppressed people. And anti-colonial thinkers and leaders taught us to give voice to them and their struggle.

Ukraine is in a similar struggle. It is often forgotten that we suffered centuries of Russian imperialism, not least under Stalin during the Soviet period. That eased to some extent under Khrushchev.

Yes, Ukrainian was taught in schools, but mostly as a second language. Yes, Ukrainian culture was allowed, but often it was reduced to exoticized stereotypes. Beyond this superficial recognition of Ukraine, Russia – its language and culture – still reigned supreme. If you really wanted to make it, you had to write in Russian, adopt Russian culture, and follow Russian artistic norms.

This cultural chauvinism has only intensified in Putin’s Russia. As it was demoted internationally by the US, the Russian elite dreamed of restoring its rule over its past colonies like Ukraine to restore its sphere of influence. Of course, that brought Russia into conflict with the US, which remains the global hegemon.

In this conflict, Russia can in no way be considered a different project than the US and the rest of the capitalist powers. Just like them, Russia is a neoliberal capitalist state fighting for more land, resources, and profit. Its rulers don’t care about improving the lives of everyday Russians who are exploited and oppressed.

In some cities like St Petersburg conditions are better. These have better infrastructure, wages, and pensions. But outside them, the country is dilapidated. Here in Ukraine, we hear that from captured Russian soldiers, usually drafted from smaller, poorer towns. They are absolutely shocked to see simple things like paved roads in Ukraine’s villages and countryside.

The Russian regime, state bureaucracy, and oligarchs have fleeced their own country and now rule through repression and deflection of popular attention onto external threats of regime change and imperial fantasies of rebuilding their lost empire. That has led them into challenging the US and gaining at least tacit support from China.

This inter-imperial dimension should not prevent us from recognizing the centrality of Ukraine’s fight for independence from both Russian and Western Imperial domination. And the imperial competition should not prevent us from seeing the common international class interests that cut across the conflict.

There are Russian oligarchs that exploit Russian labor. There are US oligarchs that exploit US labor. There are Ukrainian oligarchs that exploit Ukrainian labor. And there are Chinese oligarchs that exploit Chinese labor. And transnational oligarchs exploit us all. That class analysis points to our common interests against this band of warring capitalist siblings.

Let’s turn to a discussion of the development of oligarchic capitalism in Ukraine, which you analyze in your book, Ukraine and the Empire of Capital. What are its economic features and political characteristics? How does the current president, Zelensky, fit into these patterns or depart from them?

The last several decades have witnessed a massive expansion of the empire of capital. It swept through the global South after its developmentalist projects were undermined, weakened, and failed. The empire of capital did the same in Eastern Europe and Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Russia inherited all of the USSR’s legal responsibilities, obligations under international treaties, currency, and access to capital. Under pressure of the system and its neoliberal advisers, Russia underwent massive privatization, oligarchs took advantage of free market policies to concentrate capital in their hands, and Putin built a new repressive, neoliberal capitalist state to oversee the country.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the other former republics were suddenly independent, without their own currency, and bereft of capital. In that situation, they had no choice but to turn to the international financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank.

Ukraine established its relationship with the IMF in 1992. Under its tutelage, the new Ukrainian government privatized state property, which was almost everything in the country. Of course, people had their own personal property like cars. But almost everything else from land to housing was owned by the state.

Housing, for example, was built by the state and given to workers attached to particular enterprises. Suddenly all of that was sold off. Workers could privatize – or “buy” – their homes on the cheap, which is why home ownership is so high in Ukraine.

The same program of privatization was carried out in state industry. Shares were created for enterprises and distributed to workers as vouchers. But workers, who were impoverished by runaway inflation, needed cash to maintain their lives, and so sold the vouchers to managers. Similar things were done with land, water, and services – with a degree of regional and sectoral variation. The managers just gobbled up the country.

Essentially, we witnessed what Marx calls the primitive or original accumulation of capital. And there was a lot to accumulate for the new capitalist oligarchs. In the Donbas region, for example, there is heavy industry and lots of natural resources like natural gas, iron ore, minerals, and coal. The oligarchs-in-the-making just scooped most of it up.

In the process of seizing these properties, the oligarchs and their political and criminal networks built successful financial industrial groups. They are comprised of both enterprises and banks. These conglomerates are highly concentrated and diversified.

They wield this capitalist power to control politics directly and indirectly. Some oligarchs became politicians. Others used political proxies. They secured consultants, PR agencies, and political technologies trained in the West to create electoral constituencies to win elected office.

Their control of the state enabled them in turn to further accelerate accumulation in the 1990s. They had a free hand as European capital was preoccupied with Central Europe, Russia was weak, and multinational capital was not yet in the game. So, they plundered state property for their own enrichment.

These oligarchs also competed with one another. This competition overlapped with territorial and linguistic divisions between Ukrainian and Russian speakers. The oligarchs stoked these divisions for their own political gain during electoral campaigns. In the process, The oligarchs turned preexisting and largely non-conflictual differences into new animosities and prejudices.

This was an effective strategy to divide and rule the population that kept resisting the plunder with waves of resistance from below, from the Orange Revolution in 2004 and the Maidan uprising in 2013. These divisions were further amplified by the different oligarchs’ relationships with the EU and Russia. They would play up the divisions to stake out relations with either of those powers.

All of this came to a head during Maidan. People rose up against the oligarchs and the government, right-wing nationalists exploited it, and their parties tried to highjack it. Russian separatists then set up their so-called republics, Russia seized Crimea, and the armed conflict emerged in Donbas. The fascist Azov Battalion developed in this process.

But let’s be clear: Ukraine is not the hotbed of fascism that Russian propaganda claims. For example, the far-right parties were trounced in the 2014 elections. Their vote went down dramatically and the lost seats.

The election of Zelensky was a popular rejection of the chauvinist divisions and an expression of hope for peace. He’s an interesting figure. Behind him are a set of oligarchic forces and campaigned based on a promise of peace and anti-corruption albeit naïve.

In the end, he’s ruled like every other neoliberal politician, failed to secure peace, and oversaw ongoing corruption and oligarchic plunder. On top of that, he was exposed as incompetent at ruling. His rating went down as their standard of living plummeted.

Before the war, it is highly unlikely he would have been reelected. But now he’s a war hero and guaranteed to win a second term if Ukraine exists as a nation-state with a democratic electoral process at the end of this war.

So far, we’ve mostly talked about the role of Russian imperialism in Ukraine. What about Western imperialism, especially its economic policies?

We have endured the dictatorial rule of the Western states and their international financial institutions (IFIs). They have carried the prescripts laid out by Francis Fukuyama in the early 1990s that the free market and its logic of capitalist competition should be unleashed.

IFIs granted loans on the condition that the state withdraw from ownership of industry and services, deregulate the economy, weaken labor rights, and give preferential treatment and protection to investors all to supposedly improve the economy’s competitiveness. The state’s new role was reduced to maintaining social order.

In other words, protect the rich from the poor. Thus, far from democratizing the society, the free market prescription enables the authoritarian turn we have witnessed in Eastern Europe, Russia, and Ukraine.

The European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the IMF, and the World Bank allowed only certain types of economic and political policies. These neoliberal edicts were purportedly designed to improve competitiveness and efficiency, claims that are all of course debatable. In actual fact, they enabled the rise of the oligarchs and their competitive, semi-criminal, and in some cases openly criminal scramble for ownership of privatized industry, services, and land.

What they certainly did not accomplish was efficacy in public services. Why? Because if services are subject to competition, they inevitably exclude people by placing market-set prices on them. That undermines basic provision of universal services in everything from education to healthcare, which in turn weakens the social reproduction of capital’s labor force. Austerity flows from neoliberalism. And far from expanding the economies of countries, it actually impedes their growth, producing underdevelopment.

Ukraine is a paradigmatic example. It was an industrialized economy with developed infrastructure, healthcare, public services, and a highly educated and skilled labor force. The Western imposition of neoliberalism destroyed it. In 1991, its economy was the size of France; now it is the poorest country in Europe. That was not by accident. That was by design.

Each round of EBRD and IMF loans only make this de-development even worse. We are literally drowning in debt like countries in Africa, Latin America, and the rest of the post-Soviet region. Ukraine owes various international financial institutions and states $129 billion, which is nearly 80 percent of our GDP.

How have Western and Russian imperialisms’ interactions with Ukraine’s rulers led to the divisions within the country, especially between Ukrainian and Russian speakers?

They have magnified such divisions. One key example of the dynamic that led to the Maidan uprising in 2013-4 and its aftermath. Then President Yanukovych had been planning to sign an association agreement with the European Union but backed out at the last minute.

Despite being a criminal oligarch, he had a point. There were a few instances where he actually hit the nail on the head. The agreement was not favorable for Ukraine, so he refused to sign it to everyone’s complete shock. That triggered protests, which the government brutally repressed, setting off the mass uprising and the entire sequence of events I’ve described.

People were so surprised because Yanukovych knew the agreement’s terms all along. So, he did not back out of it because of concern for Ukraine. The real reason he didn’t sign it was that Russia and Russian-associated oligarchs pressured him to back out.

Many of these oligarchs’ assets are based in Donbas in energy-intensive industries that depend on affordable Russian gas and oil for their production lines. These oligarchs started spreading the word that if the agreement was signed, energy prices would go up – as Russia was indeed threatening, industries would close, and people would lose their jobs. This is in contrast to the Western section of the country, which has been historically tied to Western Europe. And businesses tend to be oriented more on that market than Russia.

Of course, it’s more complex on the ground; business interests do not align simply along those territorial divisions. Nevertheless, the imperial conflict deepened divisions between oligarchs who then forged electoral constituencies based on allegiances to the West or Russia making new territorial divisions very prominent.

Once this took hold, the different oligarchic blocs and their politicians used threats to limit language rights to disguise their ongoing austerity measures, deflecting class anger into linguistic and cultural conflicts. That led to the emergence of the far-right Ukrainians and Russian separatists, with each side increasingly dehumanizing the other.

This is really disgusting politics. The oligarchic political factions made things out to be a civilizational choice between the West and Russia. The Western-oriented ones presented the EU – which, we must remember, is the source of so much austerity – as the hope for freedom and democracy beyond the Soviet past.

The Russian-oriented ones depicted Western Ukrainians as Russophobes and fascists threatening the linguistic rights of Russian speakers. They portrayed Russia as the last hope to defend them against this tidal wave of reaction.

So far, we have mainly talked about the imperialist powers and Ukraine’s ruling class. What about the struggle of workers and the oppressed against the oligarchs and politicians and imperialist powers? What political and organizational obstacles have they run into?

Under the conditions I’ve described of oligarchic capitalism, we’ve witnessed growing civil resistance. That found expression in the Euro-Maidan uprising, especially after the police brutalized the protesters. People had finally had enough. The police brutality tapped into years of pain and frustration with all the corruption, anger at police collusion with the oligarch criminal networks, and their repeated ability to escape any accountability for their abuses.

All of this resistance was reactive; it wasn’t guided by a clear sense of an alternative program and set of demands. That enabled the right to highjack the revolt. They were organized and had forces to throw into the struggle. The ensuing conflict between Ukrainian government and the separatists partially dampened down the civil struggle.

But over the last few years, frustrations with the oligarchs and corrupt politicians deepened, and they repeatedly threw out one group of them to see another equally awful group replace them. Thus, it’s a proper crisis of representation. There is no clear alternative yet capable of mounting a political challenge to the oligarchs and their politicians. And the left is sadly still rather small.

At the same time, there is popular struggle outside electoral politics, particularly among trade unionists. This emerged outside the old USSR unions, which were essentially company unions. New independent unions have developed within key industries (and even some small and medium size enterprises!). One such important union is in the railroad industry, which is the biggest employer in the country.

They have been a key element in the resistance to Russia’s invasion. They have brought supplies to aging people under artillery fire. The mining unions have been particularly important, fighting against pit closures and defending wages and benefits. Medical workers have also started to organize.

People have learned that if the politicians don’t enact changes, you must do it yourself through collective struggle in your workplace. They’ve even consulted the bigger unions and confederation internationally about how to organize.

This has really expanded in the resistance as people look to one another for solidarity and support. In the last weeks, workers at various enterprises have taken it upon themselves to distribute goods to meet people’s needs amidst the war, lots of anecdotal evidence of that from different cities. For example, workers at a local food warehouse learned that there were refugees in need of food or construction material warehouse managers gave away good of use for city fortifications. Talk about expropriating the expropriators!

In the midst of this war, the resistance affirms people’s ability to affect change. That will be important after the war as the battle over how to rebuild it and in whose interests becomes the central question. I really hope that that spirit of collective solidarity can forge a new path for Ukraine once this hell is over.

This would open up new opportunities for the Ukrainian left. We will have to adapt our language a bit to make our program make sense to people who have really bad associations with the Stalinist past. Nevertheless, people are looking for collective social solutions to deep problems in Ukrainian and global capitalism.

Socialists have to merge with these struggles for immediate improvements in peoples and demonstrate that we have crucial ideas for how to rebuild our society. If we can do that successfully, we can help overcome the crisis of representation that has plagued the waves of resistance and offer a genuine alternative to the oligarchs and the right.

One development that Putin and the campist left have exaggerated for their own political purposes is the emergence of the far right in the country. What is the truth about the far right in Ukraine? How did it develop, what are its various forces, and how influential are they in the political system and the military?

This is a very important and, frankly, scary question. Because the truth is that politics in Ukraine is on a knife edge, and it could go to the right, not just the left. While I agree with you that the right’s role and importance has been exaggerated, it is also a real factor and threat.

It has, of course, been exaggerated by the separatists, Putin, and their strange supporters in the West. They have pointed to people wearing Nazi symbols and paint Ukraine as a government and nation of fascists, or at least ruled by them. This is completely untrue. Support for rightwing parties has declined dramatically.

And the truth is that the majority of people even inside the Azov Battalion do not realize the Nazi associations of the symbols they are wearing. They don’t know the history of Stepan Bandera; they see him as a some who fought for Ukraine’s freedom. But some are very aware of this Nazi past and are fascists, especially in leadership of some of the rightwing parties and the Azov Battalion. That makes me deeply concerned about them as a threat.

So, it would be a mistake to dismiss the threat of the right. The rightwing parties are small but significant force, and so is the Azov Battalion, even if it is a small portion of the overall military. Azov is quite strong. It runs the summer camps to recruit people into their ranks. And it can gain support as their forces are being hailed as heroes of the war in defending Mariupol.

These rightwing forces represent a threat to the future of a multiethnic Ukraine. They have pushed for terrible language laws that discriminate against Russian speakers. Not only are these wrong, but they will also feed the narrative of the Russian separatists.

Of course, Ukraine needs to decolonize and de-Russify. Russian remains the primary language for the most part. And, just to be clear, Russian speakers are not in general oppressed. But Ukrainian speakers have been.

For example, when I went to school, I was bullied for speaking Ukrainian. But the solution is not to mimic the colonizer in the process of decolonization and repress Russian and Russian speakers. There must be equal language rights, not new forms of discrimination. This will be an urgent question in the process of rebuilding the country.

I am for the victory of Ukraine in restoring its borders and ending the Russian occupation. But that will open up a whole process of reconciliation of the cultural conflict that the oligarchs and their politicians manufactured and weaponized. This will be challenging because Russia’s invasion has stirred up a healthy degree of Ukrainian nationalism, especially when Putin’s pretext for the war was that your country was not even a country. We have to prevent that turning into xenophobia and ethno-nationalism.

We will have to transcend the desire to dig through history and refurbish old and problematic symbols in an effort to prove we’re a nation. Instead, we need to seize the historic opportunity to reconstruct Ukraine as a multi-ethnic, multi-religious country in which all minorities have equal rights to their language, schooling, and culture.

That is the task of the left and working-class organizations, and it will entail challenging the rule of the oligarch, their politicians, and the right. The politics of solidarity must triumph; otherwise we risk confirming Putin’s obscene lie that we are a nation of bigots and fascists.

That raises the question of what the outcome of the war will be. It seems that Putin has been forced to retreat from his aim of regime change, now trying to lay waste to the western part of Ukraine and partitioning the country, securing control of Donbas as a land bridge to Crimea. What impact will that have on Ukraine, the resistance, and the political economy of the country?

If you asked me this question just three weeks ago, I would have said that if Putin agreed to retreat and just hold onto these so-called Republics, Ukrainians might accept it. But now, after the horrors of this war, the destruction of Kharkiv and Mariupol, the horrors from the outskirts of Kyiv, and the enormous number of lives lost, brutalized, and people displaced, Ukrainians will not compromise.

The Ukrainian people have tried everything to put an end to this nightmare. We tried peace talks through the Minsk process. We held to a ceasefire even under fire in order to deny Putin the excuse to launch a war. None of it worked. The so-called peace process ended up paving the way for Putin to invade the country in a completely unprovoked attack. They have been planning this for years, blackmailing people, lying about events, and sending thousands of sleeper agents to infiltrate the country, identify targets, and plant radio signals on them.

Now we have thousands dead, millions displaced, and hundreds of millions of dollars in infrastructure destroyed. After all of this, few will agree to surrender whole parts of the country to the invaders. Ukrainians are realizing that if we do not win this war, there will be no Ukraine. If there are occupied parts of the country, there will be an insurgency against Russian forces who will be plotting another war. There will be no peace.

Putin does not recognize Ukraine’s right to exist independently and so we have to fight back. We will not accept the partition of the country into something like North and South Korea. That means a long fight, but people will carry it out.

There is a lot up in the air right now. The outcome depends on if we are able to secure arms to defend ourselves and reclaim our country, if we’re able to stick to our demands in these so-called negotiations, and if the Russian regime collapses. But we will not settle for anything less than the reunification and independence of Ukraine.

There is a significant debate in the international left about what position to take on the war and what demands to raise. What do you argue we should do?

Again, the international left must put its decolonial hat on in thinking about Ukraine. We are fighting Russia, our historic imperial oppressor. We’ve been politically, economically, culturally, and linguistically dominated and colonized for a very long time.

I think some people still get their vision clouded by a one-dimensional opposition to US imperialism alone. But the US is not the aggressor in this situation. Russia is. Of course, NATO is a factor, but not the determinant one. Should NATO exist? Of course not. It should have been disbanded a long time ago. We all agree on that.

Let’s focus on the central issue: Russian imperialism and the Ukrainian liberation struggle. Putin’s made it very clear for years that he doesn’t recognize Ukraine as a separate entity, claiming in his recent statement that country was created by the Bolsheviks. He wants to reclaim Ukraine, subject it to Russian rule, and has been pursuing that militarily since 2014, carrying out a completely unlawful, fabricated, violent partition of the country.

The international left must be in solidarity with Ukraine as an oppressed nation and our fight for self-determination. That includes our right to secure arms for our fighters and volunteers to win our freedom.

But the left must not support calls for closing the skies, essentially a demand for a NATO-imposed no fly zone. That would mean an air war between US and European fighters and Russian ones, risking a wider war between nuclear powers. Just look at what US interventions have done in other parts of the world like Iraq and Afghanistan.

The US and NATO fighters would not care about care about the damage their air war would cause in Ukraine. They would order us to evacuate the cities so that they can carry out a full scale military assault on Russian forces, furthering wrecking our country and inevitably killing more Ukrainians in the process.

In the aftermath, we will need some kind of peacekeeping force, perhaps UN peacekeepers. But that is difficult, as the UN is a fundamentally undemocratic organization with powers including Russia on the Security Council that can veto such a force. But we will need some international forces subject to some sort of oversight to prevent more conflict. A new international security order will need to be built, with automatic suspension of aggressors, no vetoes, no permanent members of a security council, with real mutual guarantees so that future suffering can be prevented in a demilitarized world.

Source > Spectre

The Anti*Capitalist Resistance Editorial Board may not always agree with all of the content we repost but feel it is important to give left voices a platform and develop a space for comradely debate and disagreement.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women