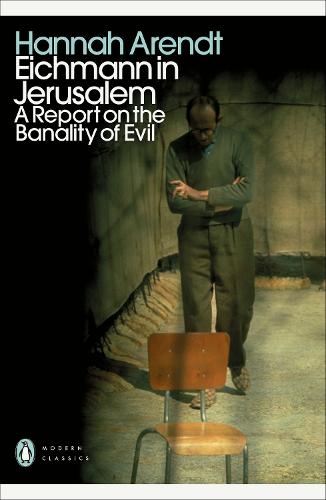

Hannah Arendt is among the 20th century’s greatest and most influential philosophers. Among her masterworks, one stands out as her most important and famous: Eichmann in Jerusalem. In this book, Arendt introduced the world to her most well-known theory, the banality of evil. Despite this popularity, or perhaps because of it, the idea is regularly misunderstood as suggesting that men such as Adolf Eichmann were “unthinking” in their evil and, in some sense, not responsible. The theory is therefore accused of minimising the severity of the Nazis’ evil, bringing their heinous crimes within the realm of possibility for regular folk.

This is inaccurate. While Arendt did believe everyday people were capable of great evils, her characterization of such evil as “banal” was not intended to suggest that the source of evil was an inbuilt tendency of human nature. On the contrary, banality is a social category, historically contingent rather than essential. Arendt intended to shift our analysis of the Holocaust from moralistic denunciations of the Nazis as somehow ontologically evil and instead to the social and historical forces which allowed that evil to take root.

In an ironic twist, the moralistic framework that is the subject of Arendt’s analysis is the very thing that has led her critics to misunderstand her. While she intended to undermine the worldview that can only conceptualize radical evil as demonic, her critics attempt to understand her theories from within that worldview. Since Arendt eroded the ontological distinction between good and bad people, and since radical evil is necessarily demonic in the moralistic view, Arendt can only be understood as suggesting that all people are demonic.

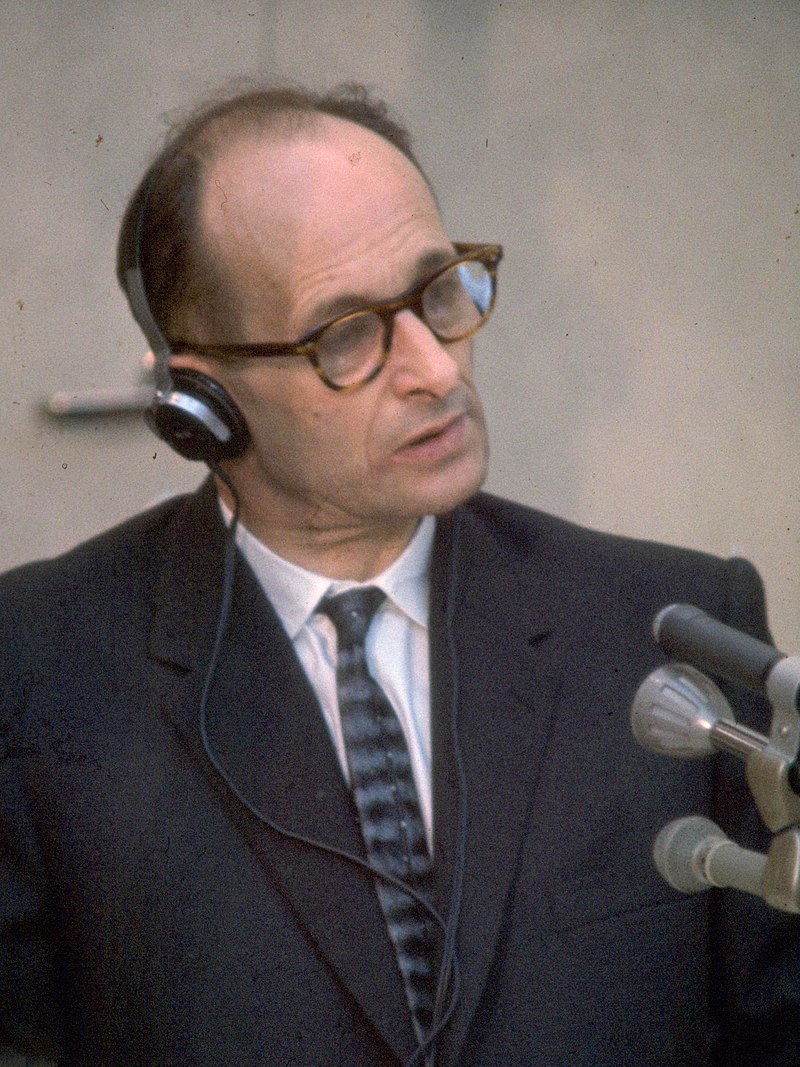

To illustrate the limitations of the moralistic worldview, Arendt used SS officer Adolf Eichmann as a case study. Responsible for managing the logistics of the mass deportation of Jewish people to ghettos and concentration camps in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe, few can claim to have done more harm in their lives. Nevertheless, in her reporting of Eichmann’s 1961 trial for crimes against humanity, Arendt found the man “terrifyingly normal,” describing him as “neither perverted nor sadistic.” Others concurred, with a panel of six psychological experts concluding that he displayed no signs of a behavioral disorder, going so far as to summarize their findings as the discovery that he was “more normal than normal.”

Such evaluations led many to incorrectly surmise that Eichmann was a mere bureaucrat, opportunistically advancing his career by mindlessly stepping atop the bodies of his victims. Indeed, Eichmann attempted to depict himself this way during his trial, stating, “I never did anything, great or small, without obtaining in advance express instructions from Adolf Hitler or any of my superiors.” This was indisputably a lie.

Far from unthinking, Eichmann and Nazi officers like him had significant room for creativity in carrying out orders from above. Each officer tried his best to act in a way he believed would embody the spirit of Adolf Hitler most perfectly; in many cases, officers spoke of hoping to essentially out-Hitler Hitler. Eichmann himself said as much, once invoking Kant’s categorical imperative theory to express that his intent was always to enact the spirit of his orders rather than their mere letter, directly contradicting his claim to only act on the express permission of those above him.

One on hand, Eichmann was a psychologically average man who displayed no noteworthy abnormalities, a boring ‘desk murderer’. On the other, he bragged about how “I will leap into my grave laughing because the feeling that I have five million human beings on my conscience is for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction.” The difficulty of analyzing Eichmann lay in squaring these facts, and it was Arendt’s brilliance that she could.

Arendt, far from denying the role of creative thinking in Eichmann’s evil, sought to socially contextualize that creativity. In her view, evil is not the result of a failure to think but a failure to think critically. In an echo of G.K. Chesterton’s views on bigotry, Arendt wrote that “the longer one listened to [Eichmann], the more obvious it became that his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think, namely, to think from the standpoint of someone else.” It was not that Eichmann was incapable of thought per se, but instead of thought that went beyond the slogans and dogmas handed to him. Contrary to the claims of Arendt’s critics, Eichmann’s fanaticism for Nazi ideology reinforces her point rather than undermining it; the mistake the critics make is in their equation of zealotry with psychopathy.

Arendt’s profiling of Eichmann’s life showed that he tended to seek out and become a member of tight-knit communities, such as the YMCA, Wandervogel, and Jungfrontkämpferverband in his youth. When he could not join the Schlaraffia in 1933, family friend Ernst Kaltenbrunner encouraged him to join the SS instead. After World War II, Eichmann felt depressed because he no longer had a sense of belonging to a group. Arendt argued that Eichmann’s actions during the war were not motivated by evil intent but by his blindly loyal dedication to the regime and his need to feel part of something. Eichmann himself admitted that the prospect of leading a “leaderless and difficult individual life” without orders or directives was daunting.

Therefore, Eichmann’s evil did not come from a place of unthinking, but from groupthinking. Eichmann believed that by participating in the Nazi project, he would be a part of something grand and historically significant; he would achieve immortality through his deeds, which society would approve of in the aftermath of a Nazi victory he wrongly thought inevitable. In his trial, Eichmann went so far as to take credit for crimes he had not committed; he preferred to present himself as not merely a good Nazi but the best Nazi to life itself. Again, showing her awareness of Eichmann’s fanatical nature, Arendt would write, “bragging was the vice that was Eichmann’s undoing.”

In a final illustration of this truth, we may turn to Eichmann’s willingness to violate orders, but only when they contradicted what he took to be the fundamental ethos of the Nazi worldview. When, in 1944, Heinrich Himmler, in a desperate bid to attain leniency, ordered Eichmann to “take good care of the Jews, act as their nursemaid,” Eichmann instead, in Arendt’s words, did “his best to make the Final Solution final.” In his mind, Eichmann remained loyal to Hitler, whereas Himmler had turned apostate. This disobedience suggests complete submission to a framework of thought rather than to the Nazi bureaucracy.

Arendt insisted Eichmann’s professed fidelity to the Nazi cause “did not mean merely to stress the extent to which he was under orders, and ready to obey them; he meant to show what an ‘idealist’ he had always been.” By “idealist,” Arendt means ideologist. The ideologist is willing to sacrifice their moral convictions and personal desires when they come into conflict with the demands of the ideology; for Eichmann, this included a willingness to kill his father on the condition that his father was a traitor to the Nazi cause. For the ideologist, ideology provides the ground of meaning. As such, any sacrifice made in its name is justifiable if it is necessary to maintain the integrity of that groundwork.

So, in what sense was Eichmann’s evil banal? It was banal insofar as it was a precondition for entering and a requirement for remaining within the world of the Nazi party. Arendt argued that, having sat in on the Wannsee Conference, Eichmann saw German civil servants and “respectable society” enthusiastically receive Reinhard Heydrich’s program for the Final Solution of the Jewish question.

To be responsible for such a crucial part of the execution of such plans would be an honor for Eichmann; not because it fulfilled a deep-seated personal hatred of Jewish people, but because it would be grounds for praise and approval from his reference group, the people whose judgment and evaluation determined his self-worth. It was banal because, within the walls of Nazi party meetings, he was fulfilling a social and ideological role. As astounding as his evil was in the context of global society, within his subculture, it was expected.

If this seems to conflict with Arendt’s portrayal of Eichmann as an ideologist, it is essential to understand that Arendt did not believe Eichmann’s antisemitism was inauthentic or just for show. Eichmann did hate Jewish people; but, and this is critical, such conclusions were not reached by way of an independent thought process. He rightly rejected the notorious Protocols of the Elders of Zion as the Czarist fabrication it was and denied the charge of blood libel against the Jewish people, an antisemitic canard that accuses Jews of killing Christian children and using their blood in religious ceremonies. Insofar as this is the case, Eichmann can be credited with a modicum of credulity.

In justifying his crimes, Eichmann instead appealed to the “fatherland morality” that possessed his spirit and to the duty he owed to the German state. To quote Roger Berkowitz in the New York Times, “Eichmann was an antisemite because Nazism was incomprehensible without antisemitism.”

For an analog, how many young Marxists today feel the need to deny the Holodomor simply because they think, as Marxists, that they must uphold the honor of Joseph Stalin and maintain the view that the USSR was a society worth imitating? As someone who fell prey to this thinking at a young age, I suspect the number is disconcertingly high. Stalinists may retort that denying the Holodomor is a radical position that contradicts the views we are taught in school as children and, therefore, cannot be adopted unthinkingly.

This truth may be ceded to the Stalinist with no consequence, as to accuse them of ideologist thinking is not to accuse them of being unthinking. While many thousands begin as Marxists and become Holodomor deniers, the number of people who start as Holodomor deniers and become Marxists must be minimal. This suggests, as do Arendt’s ideas, that Holodomor denial is born out of ideological need more so than from an evaluation of the facts. One denies the Holodomor to fit in with a group and to adhere to a worldview that is taken as valuable in and of itself.

As compelling as I find it to be, the banality of evil is hardly comprehensive. Nor is it intended to be, but accepting it still leaves us with many questions needing answers. Chief among them is that since Arendt presupposes the existence of evil, she only explains how evil spreads and not how it originates. She also gives little suggestion as to why anyone would choose to ingratiate themselves with groups that perpetuate evil over ones that do not. Finally, the theory does not explain why people require reference groups and ideologies. Answers to these questions can be found in Arendt’s books; their scope far outstrips the purpose of this article.

What Arendt’s theory does, even accepted in isolation, is explain how ordinary people can be roped into movements whose beliefs they inauthentically (but sincerely) believe in. By undermining the ontological theory of evil, in both its religious and naturalist form, Arendt makes viable questions regarding how to stop the spread of fascism and other reactionary movements. Moreover, it suggests that fascists are better at meeting the psychological needs of specific subsets of people (namely, of course, middle-class cishet white men), and while it provides no clue of how we might do better in this regard ourselves, it points us in the direction of answering the question.

In The German Ideology, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels famously state that “communists do not preach morality at all,” and several further quotations and citations could be mustered to illustrate the extent to which they sought to distance themselves from the moralism they felt characterized utopian socialism. Despite this, Marxists have never been particularly concerned with unearthing the moralistic tendencies within themselves, even when they wrote scathing critiques of the matter conceptually.

Contemporary Marxists like Jonas Čeika have valuably begun to work through this issue, but further work is sorely needed. Arendt’s banality of evil, while no replacement for a holistic critique of morality, nevertheless represents a handy heuristic that, when properly understood, can be quickly and intuitively deployed to undermine moralistic strains in our own thought.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Protest Review Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women

good article! ^ ^

the point about the moralistic framework’s twist and misunderstanding the banality into suggesting that all people are demonic, is really good!

that’s such a big heart of moralism, and why “good people” is such a dangerous notion.

the point about Eichmann being “more normal than normal” is, in context somewhat frustrating but also good too – as you said, the error in equating zealotry with psychopathy – brewed, of course, with typical social aggressive bias & ignorance of “weird, crazy” people.

which after all, again plays right into the game of “good people” and “demonically evil human monsters”

Eichmann’s thing about leaping into his grave laughing, is to me a very -basic- kind of display of the drive to immortality.

also, the point that he understood the Protocols of the Elders of Zion & blood libel to be things to reject, but then placed the whole of his self into “fatherland morality” really just says it all, doesn’t it. The most egregious kind of truly pathetic groupthink!

the point about Holodomor denial, Stalinism, Marxism is a very good basic kind of return point! Also as you pointed out, difference between unthinking and ideologist thinking! it’s far too easy for people to simply crow on about “unthought”, as if that’s the real major issue.

also, your point about Marxists criticising morality conceptually but not unearthing their own tendencies, is really useful and absolutely you should continue with as well! a lot that can be covered there, and the tendancy of automatic, simple denunciation via disgust should always at least be brought around back into consideration.

overall, nice piece, good to counter the Milgram style popular bs, and a great jumpoff point! : 3