In an early piece of dialogue involving the protagonist of Fernando León de Aranoa’s new cinematic character study, we glimpse the inner workings of Julio Blanco. “What are you thinking about?” asks his wife Adela, as they sit in the lavish garden of their mansion. “Nothing,” he replies. “It’s impossible to think about nothing,” she retorts.

Later in The Good Boss (El buen patron, 2021), when events have spiraled into chaos and Julio’s nihilistic bent is more apparent, this conversation is repeated. The superficial implication behind the refrain is that beneath his quite empty exterior, Julio has nefarious depths. But the greater truth is contained in his first insistence that he is thinking about nothing, which becomes much more apparent in the denouement. His goals, his ideas, are trivial. This is a man without much substance, whose power has robbed him of the social ties needed to be more than two-dimensional.

It is perhaps easier to do a character study of a person with hidden depths and sustained tensions. In this sense, Tom Ford’s 2009 sumptuous adaptation of Christopher Isherwood’s novella A Single Man is almost an inversion of Aranoa’s project here. Ford’s film was all about an elaborately disguised inner life that was in conflict with postwar American suburbia, but as Aranoa peels back Julio’s layers we discover that his disguises reveal nothing.

There is hardly any tension between him and a contemporary Spain defined here by ambitious middle-men and little napoleons. Where tensions do arise, it is between him and those who do not accommodate to realpolitik. Much like director Mary Harron’s 2000 subversive feminist take on the titular Patrick Bateman in Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, Julio is a representative of the capitalist of his day. Both are hollow men, without much capacity for empathy and with a tenuous grasp of reality, but whereas Patrick is the model of a predatory neoliberal yuppy, Julio is what Slovakian philosopher Slavoj Žižek would call capitalism with a human face.

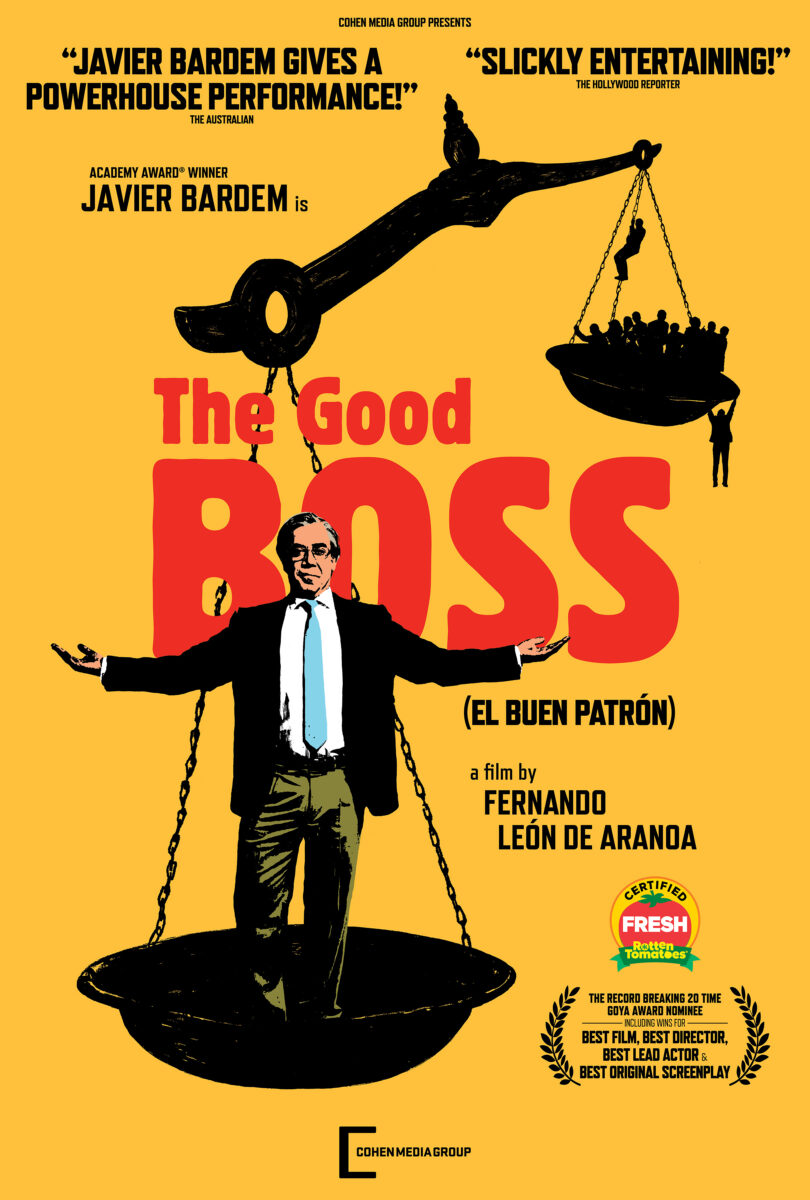

So many of the comedic moments of this film emerge in what are also its most sinister moments. “You treat me like a boss and I’ll treat you like an employee,” Julio warns one of the many of his employees (and those unfortunately associated with them) whom he manipulates to secure his prize, a provincial award for business excellence. Bardem’s performance works so aptly because he is able to be so understated. He revels in portraying the charisma of a tyrant who operates through implication and faked familial concern.

So many of the comedic moments of this film emerge in what are also its most sinister moments

Only once in the film do we get a sense of a person directing all of this Machiavellianism, a strange moment of near confession in which Julio unburdens himself to a distracted security guard, Fernando Albizu’s Román, defending his actions. In what comprises a villainous soliloquy, Julio compares himself to a surgeon who must amputate a leg. “I don’t think the surgeon likes cutting off someone’s leg,” he pleads, “but he has to do it. Just like me. I have to do it. For all of you, for your families as well. Do I want to do it? No, I don’t. But I have no choice.”

Javier Bardem’s performance is matched by Almudena Amor as Liliana, whom Julio attempts to seduce but in a series of twists ends up being his greatest adversary. Against his vicious, self-serving conniving her justified cynicism is a perfect foil. Sonia Almarcha’s Adela, like Bardem’s performance, is also aptly restrained with subtle moments hinting at a broader awareness of events.

Óscar de la Fuenta’s Jose, an ex-employee most directly threatening Julio’s ambitions with his protest, however, is a tad overperformed. As are many other minor characters. This occasionally leads the film into a clash of registers, where the taunt, suspenseful story of the Mephistophelian boss jars with the comedy-of-errors satire. Ultimately Bardem sufficiently anchors the film to avoid this becoming a major fault, but there are interactions between Jose and Román that felt as if they belonged to a different, if still interesting, movie.

Pau Esteve Birba’s cinematography felt it belonged to the film about Julio; unassuming, focused on character, with a range that did justice to the grim subtext. Whereas Zeltia Montes’s wry, more comedic soundtrack at times feels like it would be better placed in a film focused on Jose’s mishaps and his stubborn travails as Román offers him silly advice to use more assonance in his placard’s slogans.

Underscoring the tension in tone is the film’s commentary on race and gender. The opening scene offsets the narrative by depicting a brutal racist attack on Arab immigrants by a group of Spanish adolescents. This intersects with the later plot, revealing the depths of Julio’s amorality. Birba uses handheld footage to catch the sordid intensity of the moment, which contrasts with his cleaner, neatly arranged approach to most of the rest of the film. Scenes of sexual exploitation are also handled with a self-aware luridness. When these elements of the story clash with the film’s chirpier humour, the two do not fully come together quite as seamlessly as they should.

Overall, however, The Good Boss is a deft examination of someone whose alienation from others, his loss of a meaningful sense of self, perhaps his deeper inability to cultivate such a self, is precariously sustained by self-importance and the control he assumes over those he only pretends to cherish. This examination also serves as a subversive look at a Spain that tries to contain the demands of the exploited and oppressed behind the charms of fatherly if liberal patriarchs.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War