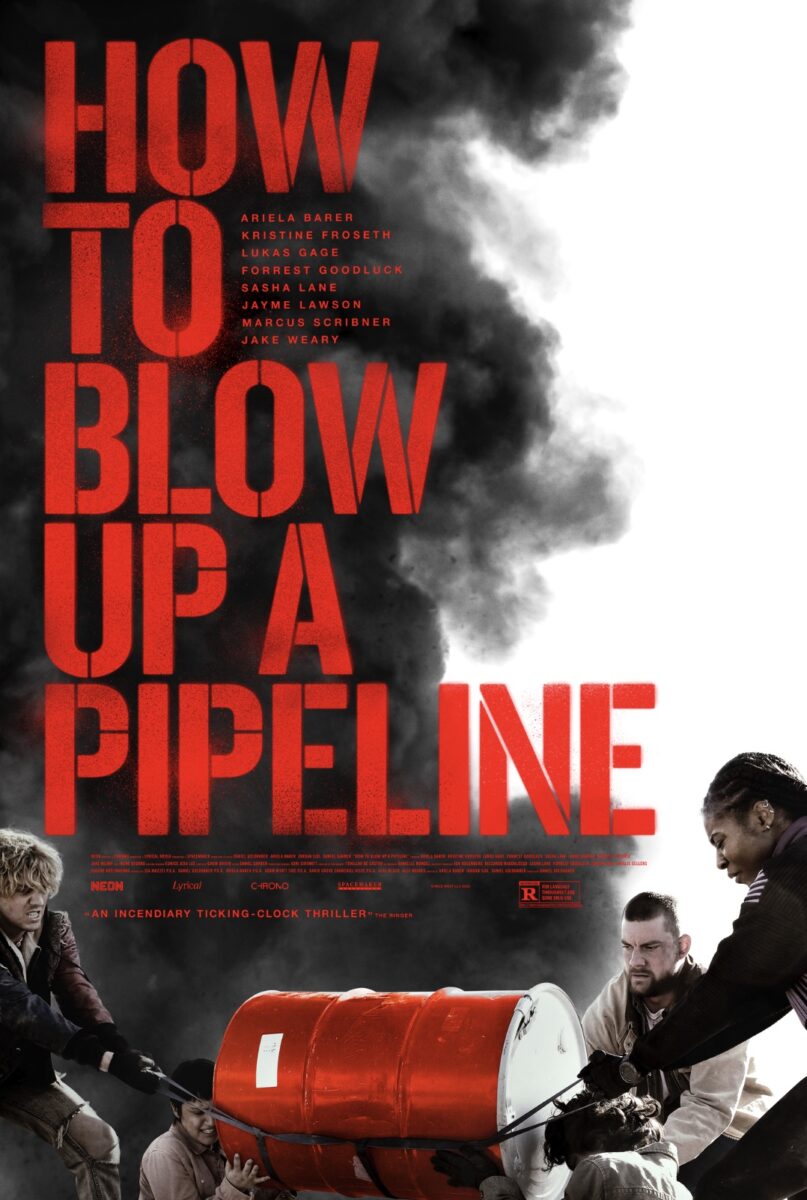

Well-paced, with pulsating tension and interesting characters, this film has the best features of a classic criminal heist movie. All the planning and technical preparations get you thinking about how you actually do something like that. The precise timing and distribution of roles take you into the heart of the action. You look around at the protagonists and see if you can work out who might be the weak link or the police informer. An original music score and neat editing maintain the tension. The simple narrative drive keeps you hooked—will they get away with it?

You can enjoy the movie without even knowing that it was inspired by a book written by a Marxist eco-activist and published by a relatively small left wing publisher. It is the first time our site has reviewed a major film that has come out of a book written by someone who did an ACR Zoom meeting with us a year or so ago!

Although the book does make an appearance in the movie when one of the protagonists is seen reading it, the film is quite an extrapolation from the book. The book is a political essay criticising the limits of a reformist or pacifist ecological approach. It advocates the effectiveness of controlled acts of sabotage against property and infrastructure in combination with building a mass movement against fossil capitalism.

“Although the book does make an appearance in the movie when one of the protagonists is seen reading it, the film is quite an extrapolation from the book.”

The film takes this basic premise and fictionalises it in a pretty realistic way. Just as Tarantino does in his classic Reservoir Dogs or Kubrick in The Killing, the film plunges straight into the heart of the crucial action as they prepare the sabotage a day or so before. Then the unfolding action is punctuated by flashbacks giving the participants’ backstories. Each character has experienced the everyday violence of the fossil fuel industry in a very personal way. One has lost their mother to an early death due to the local fuel plant; another is actually dying of an incurable disease caused by the pollution around her home; an activist of Native American origin has seen his ancestral territory trashed by corporations; and yet another has had his family farm taken away by the pipeline company.

As Malm shows in his book, fossil capital is killing people worldwide every day. Using violence against its infrastructure is responding to “legitimised” violence that is killing people, who are mostly workers and the poor, particularly in the Global South. Indeed, given this violent attack on people, the surprise is that there has not been more of a violent response.

One of the characters in the film does reflect this debate in their personal story. He is shown diligently working to raise consciousness through conventional protests and the production of documentaries, but comes to realise the limits of this action. The documentary becomes a way of dramatising a human story without any political impact. It is a way of surfing on someone else’s terrible situation in order to safely advance your career rather than actually changing anything.

By giving the colour and the details of their motivation, the film shows the rationality of their action and how it is quite different from forms of political terrorism that indiscriminately target human lives. We witness several discussions in the film about how to blow up the pipeline in a way that is not dangerous to human life and does not create pollution for local people.

“By giving the colour and the details of their motivation, the film shows the rationality of their action and how it is quite different from forms of political terrorism that indiscriminately target human lives.”

I liked the way that the characters were not idealised but shown warts and all. For example, the farm owner probably did not tick many of the other progressive boxes, and the Native American had big issues relating to his family and other people. Unlike a lot of Hollywood films, there were no cardboard cut-out good guys. They had doubts and were not particularly articulate about eco-socialist strategy, but it was all the more believable for that. The way the film is tied up at the end reflects the contradictions at the heart of all struggles. It is a little contrived, but it is credible enough.

It would be great if the film inspired people to go and read the book, which is short and not at all academic. Far from being ultra-leftist and advocating spectacular actions by elite groups, it retraces the role of sabotage and violence in all the big mass struggles of our epoch, from the Suffragettes to the Civil Rights movements and the fight against Apartheid in South Africa. In the latter case, the consistent sabotage against the South African oil company, SASOL, was an important element in weakening the regime. As Malm argues, sabotage and direct action are unlikely to bring about the major destruction of fossil fuel industry infrastructure, but a degree of escalation can inhibit future investment and put big pressure on the state, which in the end is the key terrain of struggle.

One of the characters paraphrases a well-known quote from 1968 by Ulrike Meinhoff, who had in turn borrowed it from a black power activist:

Protest is when I say I don’t like this. Resistance is when I put an end to what I don’t like. Protest is when I say I refuse to go along with this anymore. Resistance is when I make sure everybody else stops going along too.

(Malm P.79)

To be more precise, resistance acknowledges that we need systematic change. When we have to work both inside and outside the institutions of current democracy, but with the understanding that our organised power has to replace their power and the economic system that sources it.

Malm uses an insight on sabotage from R.H. Lossin (p. 68)

Sabotage is a sort of pre-figurative, if temporary, seizure of property. It is (in reference to the climate emergency) both a logical, justifiable, and effective form of resistance and a direct affront to the sanctity of capitalist ownership.

If we do not take action, as Malm says, property will cost us the earth. It is not a question of mass movement or sabotage. The former is still crucial, but direct action and acts of sabotage can help create the disruptive commotion needed to stop us from accepting business as usual. On their own, acts of sabotage do not destroy a state, but they express a potential threat and can interact with the confidence of the mass resistance.

Much has been said about the turn of Extinction Rebellion away from certain forms of disruptive direct action. Certainly, their Big One demonstrations show a new capacity to unify broader forces. Malm himself, in the book, criticises the big error made by Extinction Rebellion involving one of its activists stopping a commuter train in Canning Town (a working class area of London). Direct action still has its place. The enthusiastic response of the crowd to the Big One platform speaker saluting the two activists detained for several years for scaling the Dartford Bridge showed that the mass movement can still support such actions, even if not everybody is able or willing to make the sacrifices contingent on them.

Malm quotes the criteria developed by William Smith (p. 105) that should be invoked when proposing property damage (p. 105).

- direct action should be limited to disrupting practices that might result in or immediately threaten to generate, serious and irreversible harm.

- must be grounds for believing that mellower tactics have led nowhere, lack of progress is symptom of the structural depth of the ills.

- should be some higher charter, edict, or convention the wrongdoers have flouted and violated.

As the world warms and the effects of climate change become more visible, it is likely that people will be more receptive to radical action. The fact that this film was made reflects this reality. Inevitably, the state has responded by passing more repressive laws restricting our freedom to disrupt or offend. These laws will be backed by more draconian sentences and heavier policing. Even around the Coronation, the police have sent semi-intimidating notices to the Republic campaign and will be using the latest facial recognition technology.

All the more reason we have to embed the employment of judicious direct action within the mass movement. Building mass support for a just green transition is still the bedrock strategy for eco-socialists. A balance has to be found between taking account of the new repressive environment and refusing to be intimidated into passivity.

Art Book Review Books Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 EcoSocialism Elections Europe Fascism Film Film Review France Gaza Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Palestine pandemic Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War

Latest articles

- Unwavering support for UkraineUkraine is still resisting heroically Russia’s imperialist war of annexation writes Fred Leplat.

- Trump visit – the Emperor’s new clothesDave Kellaway looks at the key takeaways from Trump’s visit this week

- Speaking out for disabled survivorsCharlotte from the Yotkshire Feminist Collective spoke at the Women’s March in Leeds on 6 September. This is what she said:

- Don’t Help Fascists Martyr Their Dead Twilight O’Hara argues against the moralistic response of much of the left to the assination of Charlie Kirk.

- Your Party is Our Party – stop wrecking this opportunity!Statement by Anti*Capitalist Resistance Council calling for unity and a democratic conference for Your Party