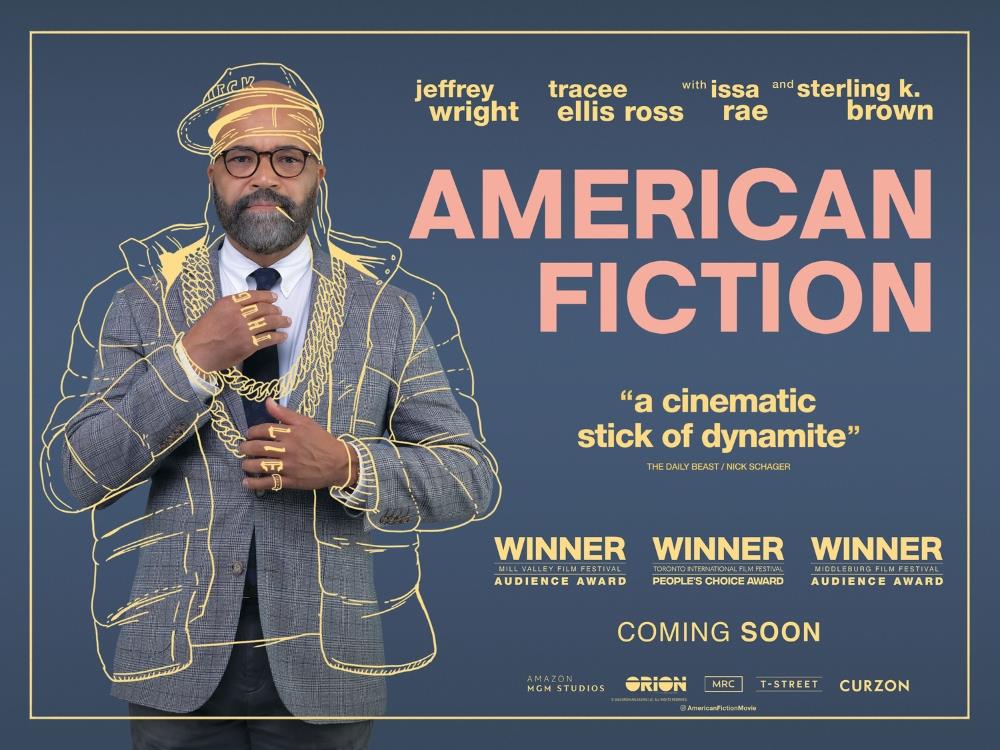

Otegha Uwagba tells the story about how he walked into a big bookshop and found one of the books he had written about money not in the economics or business section but placed on the black studies shelves. Reality is stronger than fiction. A key comic scene in this thought-provoking satire is when Thelonious ‘Monk’ Ellison, played masterfully by Jeffrey Wright, gets really angry when he finds his books about classical Greek or Roman culture dumped in the race studies area. The hapless sales assistant says it is the company that decides where the books go. So the issues this film deals with are real.

It is a laugh-out-loud satire about how difficult it is for Black creatives not to be steered into writing or making art that panders to white stereotypes of how ‘blackness’ should be represented. Monk’s rather literary academic books have some critical success but do not make much money. When he desperately needs to find money to finance his mother’s social care, he turns his hand to writing one of those books that the white-dominated capitalist publishers think are most marketable—tales of violence in the ghetto, rising or falling out of a deprived upbringing told in a ‘black’ dialect. Similar to what we have called poverty porn here on British TV (Benefits Street) in relation to working class poor people.

Much to his and his agent’s total surprise, the book is snapped up by a big publisher, and he is given a $750,000 advance. The movie with millions attached duly follows. For interviews, he has to pretend to be a convict on the run. There are hilarious scenes where he has to change his middle class, educated accent into ghetto rap and even adapt the way he carries his body or dresses himself to convince the gullible media.

Alongside the satire, we have an acutely observed drama of a high-achieving, middle class family. People die, get divorced, commit suicide, change their sexual orientation, and deal with dementia. It is almost as if the film is saying, Look, we can do the sort of stories about Black people that white directors like Woody Allen do all the time. This linked family story backs up the counterargument Monk makes against the stories publishers or Hollywood push Black writers or filmmakers into. There is a pointed exchange between Monk and the black woman writer, Sintara, who has written the Blaxploitation blockbuster that the publishers want:

Monk: You write about what interests white publishers fiending Black trauma porn.

Sintara: They are the ones buying the manuscripts. Is it bad to cater to their tastes?

Monk: I see the unrealised potential of black people in this country. But people—white people—read your book and confine us to it. They think we are all like that.

Sintara: Then it sounds like our issue is with white people Monk not me. Potential is what people see when they think what’s in front of them isn’t good enough.

As you can see, although the film basically backs up Monk’s stance, it recognises that things can be complicated. Monk comes across at times as a bit of an academic snob, looking down on popular culture and its strengths. Sintara is smarter than her book appears and pricks his academic, slightly elitist prejudices.

It makes you think of certain critics who do not consider Le Carre’s spy novels to have the same value as true literary fiction. Authenticity has value, even if Monk correctly criticises crude identity posturing or virtue signalling. At the very beginning of the film, a young woman student in his class criticises the fact that Monk examines the use of the term ‘nigger’ in southern-based historical literature. Some right wing culture war people have leapt on this scene to try and denigrate ‘woke’ culture, but they detach it from the sense and meaning of the whole film. The director and Wright have spoken out against such a crude misreading of the film.

Alongside the nuances of Monk’s literary approach, we also see the development through the film of someone who does have difficulties with relationships with family, friends, or partners. As someone says, he is a bit of a ‘tight ass’. His brother, Cliff (Sterling K. Brown), and sister, Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross), shine in supporting roles, helping us to understand Monk better in exchanges with him.

Cliff: People want to love you Monk, I personally don’t know what they see in you, but they want to love you, You should let them love all of you.

The script is very insightful, both in terms of the family drama and the comic satire. The novelist who wrote the original book and the director collaboratively wrote the screenplay, so this is hardly surprising. It is the sort of film that inspires you to go back and read the original book. Apart from the book, Spike Lee’s efforts to raise similar issues in his film Bamboozled surely partly inspired the film.

In the final denouement, Monk sits on a critics jury, having to award a prize out of a list of books that includes his spoof novel (called Fuck, a pafology). The discussion here shows the limits of white liberals gushing empathy for black people as victims, denying them agency, and failing to address the structural racism of society, the changing of which could disrupt their lives. As Arthur, Monk’s agent, says:

White people think they want the truth, but they don’t. They just want to feel absolved.

The ending is deft, adding a further story to the two main plot themes and leaving the viewer to reflect and speculate further.

Let us give the last word to Otegha Uwagba:

I’m left turning over a series of uncomfortable, complex questions long after the credits have rolled. Where does one draw the line between authenticity and pandering? Do I need to temper my disdain for Black authors who choose to “play the game”?

Art (55) Book Review (127) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (46) EcoSocialism (60) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (63) Film (48) Film Review (69) France (72) Gaza (63) Imperialism (101) Israel (130) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (56) Labour Party (115) Long Read (42) Marxism (49) Marxist Theory (47) Palestine (186) pandemic (78) Protest (154) Russia (343) Solidarity (152) Statement (50) Trade Unionism (144) Ukraine (351) United States of America (140) War (371)