We are all familiar with the cliché that we all remember where we were when big news events occur, like Kennedy’s assassination or the terrorist aerial attack on the Twin Towers. For those of us on the left at the time, we all remember where we were when General Pinochet sent in the air force on September 11th, 1973, to bomb the Moncada Palace, seat of Salvador Allende’s leftist reformist government. Tanks were sent into the centre and the workers areas, where there was heroic but limited resistance given the lack of arms.

Remembering the 1973 Chilean Coup

- The Brutal Repression of the Pinochet Regime

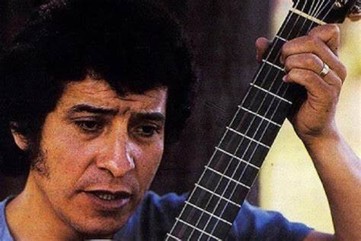

Later, the world watched as thousands of left activists were rounded up and held in the Santiago football stadium. Victor Jara, the folk singer-guitarist whose songs (link to listen) were the voice of the Popular Unity process, had his hands broken and was then murdered. His story captured the absolute brutality of the fascist coup and helped galvanise a massive international solidarity movement.

I remember being at my parents’ house after finishing university and following the coverage on the TV in the front room. My dad did not really know what all the fuss was about until I explained. Chile was not really on the mainstream news agenda.

Salvador Allende, the Chilean Socialist Party leader, had dared to challenge the interests of the local bosses and their masters in Washington. Estimates vary, but around 3,000 were killed, and 200,000 (2% of the population) went into exile. The bodies of around 1,000 of those killed have never been recovered, despite the continuing search. Years of repression, torture, and ‘disappearances’ against the left and any progressive opponents followed. Another 17 years would pass before there was a limited transition to democratic rule with the election of Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin.

Salvador Allende, as his daughter said, could have fled like other leaders, with his briefcase full of him, but he did not abandon his post. There is the iconic photograph of a man with a helmet on and a gun in his hand. Later autopsies confirmed—and his family agreed—that he committed suicide. Whatever disagreements the left may have with his strategy and tactics, Allende lived and died with the dignity of a committed progressive democrat.

Pinochet was blocked from returning to Chile in London during a visit in 1998 after international charges of human rights abuses were made. At least his fascist coup and repression were once again widely publicized. Unfortunately, Pinochet managed to return in 2000, where he died in 2006, without facing a trial or detention for his crimes. Jack Straw, the then-Labour Home Secretary, decided in the end to allow him to leave for what turned out to be spurious medical reasons. A younger Straw had helped organise solidarity demonstrations after the coup but rejected the demands of the revived British solidarity movement, Chile Democratico. Like Franco in the Spanish State, Pinochet survived prosecution until his death.

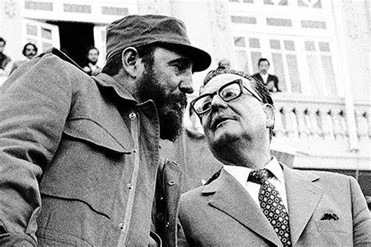

Fifty years later, it may be difficult to comprehend how important the 1970s Chilean political process was for the national and international labour movement. This was true for the reformists, who saw the Popular Unity government as the model for a democratic, peaceful transition to a socialist future without the need to confront a violent capitalist state. On the other hand, it held a different meaning for the new revolutionary left emerging from the political earthquakes of the post-1968 period with the rebellions in France, Italy, Prague, and the Viet Cong’s Tet offensive in Vietnam. For us, the key question was the development of worker and peasant self-organisation in Chile that could defend and extend the gains of the Popular Unity government. Fidel Castro visited Allende and presented him with a machine gun. This was a clear political message. The left recognised the huge risks of challenging the national bosses and their US allies without organising the means to withstand any counterattack.

“Fifty years later, it may be difficult to comprehend how important the 1970s Chilean political process was for the national and international labour movement.”

Like in a nightmare where you are trying to run and escape, the left could see the disaster that was unfolding but was relatively powerless to turn things around without preparing any armed resistance. The fascist army even organised a rehearsal with the tancazo—when tanks were put on the streets—a couple of months before the coup. This led to the government actually appointing Pinochet as commander in chief. Left groups, like the MIR (Revolutionary Left Movement) and some workers committees, who tried to agitate among soldiers and call for arms to be distributed, were rebuffed by the government.

The communist-led union federation appointed Pinochet as its military counsellor. On the very morning of the September 11 coup, the Italian Communist Party’s daily newspaper published a commentary by a Chilean Communist senator, Volodia Teiteboim, extolling the army’s loyalty and love of democracy.

Indeed, the Italian Communist Party’s conclusion was the exact opposite of what many class-conscious activists in Chile and elsewhere around the world came to. Rather than radicalising the situation by calling for workers to control their factories, land occupations by the peasants, and the development of armed militias, the Italian communists concluded that the alliance that Allende had built was too narrow.

What was needed was a historic compromise with the right and Christian democracy to ensure things did not end like in Chile. Thankfully, there was no violent repression in Italy as a result of the ultra-moderate line of the Italian CP. It did support Christian Democrat governments and went on to govern in a number of governments that carried out neo-liberal austerity policies. It dumped even its classic reformist ideology, changed its name, and made its historic compromise by merging with a liberal sector of the Christian Democrats.

The result has been the transformation of the Italian labour movement into a very weak force both politically and culturally compared to its heyday in the 1970s. Italian working people have paid the price for the soaring inequality and poverty that now exist and the arrival of a government in power today that is led by people from the fascist tradition.

Maybe the coup would not have been stopped if Allende had changed course and gone forward, responding to the demands coming from the most radicalised sectors rather than retreating. The levels of workers’ self-organisation and the size of the radical or revolutionary left were not as great as some leftist commentators imagined in Europe. Perhaps the extent of the reactionaries’ social base had been underestimated. It was never a question simply of armed struggle crudely counterposed to working in institutions.

We will never know for sure the outcome of an alternative strategy, but there was a terrible price paid for sticking to the cautious approach. There was an inverse proportion between the historical constitutionalism of Chilean society, its similarity to European society, and the furious brutality with which the left was brutally repressed. This is a lesson for us too. Societies that seem to have respected democracy for many decades can become the sites of fascist reactions if capitalist power feels fundamentally challenged. In Chile, the left was physically eliminated, and it took several generations for some sort of recovery.

Building International Solidarity

- Mobilising the Labor Movement

- Cultural Connections

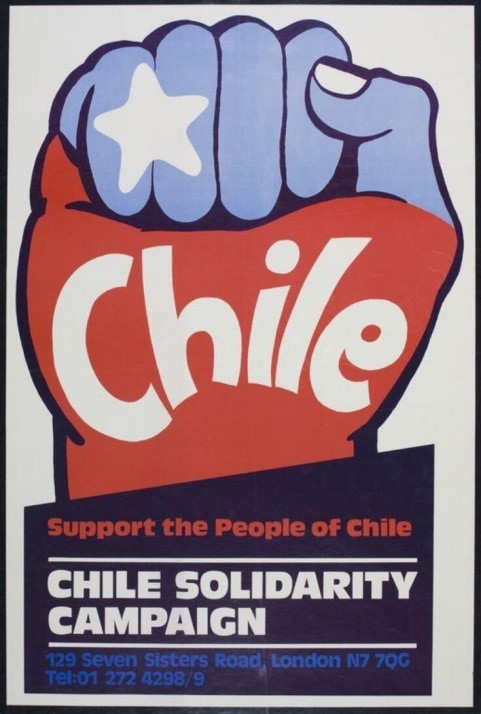

Once the coup happened, debates on strategy, while still relevant, had to be put to one side while an effective mass solidarity movement needed to be built. As in other countries where the labour movement had been following events in Chile, there was an extraordinary response. The closest comparison has to be with the movement in solidarity with Republican Spain against Franco in the 1930s and 1940s. We had to get people out and organise refuge. Around 3,000 refugees came to Britain, and about half eventually returned. To her credit, the Labour minister for international development at the time, Judith Hart, released some funds to support the resettlement of Chileans here. Although the same old Home Office was still not always helpful about providing visas, the trade union movement was heavily involved in the support networks. Most of them are affiliated with the Chile Solidarity Campaign (CSC).

The CSC brought everybody, from human rights activists to the radical left, into one united movement. I remember working with comrades from the Communist Party, the Labour Party, and left wing groups. Every major city and many smaller towns had active CSC committees, and most lived on until at least the end of the decade. Groups organised in the universities helped get academics out of Chile. We were able to mobilise religious communities as the repression targeted European nuns who were working over there. Later on, direct links with communities in Chile were developed.

Annie Street was the secretary of the Chile Human Rights Committee (CHRC), which worked alongside the CSC. The CHRC focused on the practical work of highlighting human rights abuses, supporting political prisoners, and campaigning around the plight of the disappeared. She gave me an example this week of how deep the solidarity became. In the late 1970s, she accompanied a Chilean visiting speaker on a UK tour. While in Scotland, they visited Cumbernauld, a small mining town where the National Union of Mineworkers had secured jobs down the pits for two Chilean miners. As she walked down the street with one of the Chilean wives, they were greeted continuously by passersby, who all said ‘hello Maria’. Everyone knew her, and the family had been taken into the heart of the community. Their solidarity extended to not just the two families but to the entire trade union. That example could be repeated in many communities in Britain at the time, where trade unionists got jobs for refugees fleeing persecution.

Boycotts were organised against Chilean fruit imports, but the highest form of solidarity was action by East Kilbride Rolls Royce workers who refused to service and repair engines for the Chilean air force. It actually grounded an entire squadron as the workers dumped the stuff outside the factory. Four years later, it is believed some military operation (the SAS?) organised their removal. Tory laws about boycotts and sanctions (not rejected by Labour currently) would make this sort of action illegal. An excellent film, Nae Pasaran,was made in 2018 about the action.

Pena (party), empanadas (Chilean pasties), and performances by Inti-Illimani or Quilapayun became part of the cultural life of the labour movement. Consequently, the depth and breadth of the campaign enriched internationalist work here. When General Videla carried out a fascist coup in Argentina in 1976, it was relatively easy to piggyback on the success of the CSC to build a companion solidarity movement.

“The depth and breadth of the campaign enriched internationalist work here. When General Videla carried out a fascist coup in Argentina in 1976, it was relatively easy to piggyback on the success of the CSC to build a companion solidarity movement.”

It also educated activists about the reality of US imperialism and how it intervenes to help overthrow democratic regimes when they challenge its interests. Recently, the release of official government documents shows that Kissinger, the US secretary of state, had his hands all over the blood-drenched coup. It only confirmed what the left had been saying all along.

Lessons for Today

- The Power of the People

- Never Forget, Never Forgive

The residual strength of the solidarity movement was shown in 1998 when Pinochet was placed under quasi-house arrest in Wentworth while awaiting a decision on whether Britain would extradite him to Spain or another country where international arrest warrants had been issued. Veterans of the CSC stepped up to organise pickets, demos, lobbies, and leafleting.

We must never forget that Margaret Thatcher was a great fan of the neo-liberal monetarist policies of the Pinochet regime. She shared the ideas of Milton Friedman and the Chicago Boys economists who advised the Chileans. Unsurprisingly, she never condemned the coup and lobbied for Pinochet to be allowed to return to Chile. She had a friendly dinner with him.

Personally, the Chilean events, coming a year or so after the successful British miners strike, convinced me more than ever that the real power for change is in the hands of working people. However strong their movement, they need to know their exploiters will not go quietly if their wealth and power are threatened. Nobody relishes violence in politics. It should not be used unless absolutely necessary, but without armed defence against their oppressors violence, the human toll, as Chile shows, can be even greater.

El pueblo unido y armado no sara jamas vencido

[a united and armed people will never be defeated]

Afterword: Never forget and never forgive what they have done

33 years ago they found a mass grave in Pisagua in Chile. It contained 19 tortured and murdered corpses. Humberto Lizardi Flores was identified as one of the bodies and a letter was discovered among his clothes.

Dearest mother and father.

Tomorrow I will perhaps be dead and for this I want to write these brief lines with the urgency of the situation I am in. For the last time I want to tell you I owe everything I am to you. Thanks to your guidance I have been able to live a full and true life. These years have been well lived with your love and that of others. I have fully lived and for that I am forced to leave. At the end of it all I am dying for what is just.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War

Latest Articles

- A Marxist Defence of StuffDoes marxism entail giving up the enjoyment of stuff? Echo Fortune argues for a socialist future defined by public goods and shared, creative pleasure.

- Climate change is an injustice multiplier. Not an asteroidReview by Simon Pirani of Climate Injustice: Why We Need to Fight Global Inequality to Combat Climate Change, by Friederike Otto (Greystone Books, 2025). Republished, with thanks, from the Ecologist

- Storm in a Coffee Cup – a catalogue of global warming effectsWhat does the crisis in the coffee industry tell us about global warming? Phil Hearse shows the links between climate, economy and the precarity of workers.

- Palestine: The hypocrisies of misrecognitionWhen it comes to humanitarian action in Palestine, everything is happening too slowly writes Dylan Naughten. The Biden administration held out through eight months of atrocities before calling for a ceasefire, aid trickles into Gaza at a snail’s pace, if at all, and peace talks are routinely stalled.

- How and why is our feminism trans‑inclusiveAll women, including trans women, are a part of feminism. Echo Fortune, Ally Nuttall and Paris Wilder write for RISE.