The Rebirth of Italian Communism, 1943-44 (Palgrave Macmillan 2021)

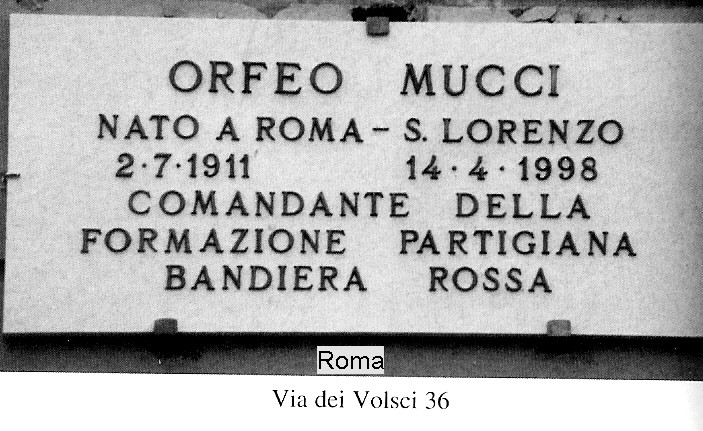

This is the story of several thousand resistance fighters in Rome who were organised as the Movement Communists of Italy (MCd’I), sometimes better known by the name of their publication, Bandiera Rossa (Red Flag). They criticised Togliatti’s PCI (Italian Communist Party) for its policy of national unity with liberals and Christian Democrat forces which effectively blocked a strategy of turning the anti-fascist struggle into an insurrection for socialism. The PCI used all its resources and some unsavoury sectarian tactics to defeat this left organisation.

These dissident communists went from leading the resistance in the poorest neighbourhoods of Rome to disintegrating as a viable organisation just a few years after the Liberation in 1944. None of their cadres wrote significant analyses of why their organisation failed. Official PCI histories of the resistance wrote these comrades out of history and even non – party histories have not treated them much better. This book is the most detailed history and certainly the only significant one in English.

The book follows in the tradition of those writers who have researched and produced honest histories of the POUM in the Spanish Civil war – who share some similarities with the Bandiera Rossa comrades – or told the truth about the left opposition and Trotskyists in the former Soviet Union. If we tell the history of the labour movement and we leave out the story of the defeated we can end up with a history that just rubber stamps the choices of the victors. It invalidates the discussion of any possible alternative. This has a bearing not just on how we read the past but can continue with the same logic into contemporary political discussions. It leads to a sort of realpolitik approach with a reduced vision based on a cynical analysis of human potential.

The book follows in the tradition of those writers who have researched and produced honest histories of the POUM in the Spanish Civil war – who share some similarities with the Bandiera Rossa comrades – or told the truth about the left opposition and Trotskyists in the former Soviet Union.

David Broder delved into the official state and city archives, read through the files of the resistance organisations, consulted Italian Communist Party bulletins, picked through the Allied armies’ intelligence documents, read the memoirs of key participants and talked directly to the few survivors or their families. For those who are not familiar with the history of those crucial years, the book provides a very good outline. The final section also makes the link with post-war politics right up to the present day. As Daniel Bensaid has shown the different times of history interact and you cannot understand the present without looking at their complexity.

Broder does not only show the relative continuity of the PCI’s reformist line from the resistance right up to its own liquidation after the fall of the Berlin Wall, he also allows us to question some of the over-simplistic revolutionary Marxist analyses of the period. Being educated in much of the Trotskyist tradition many of us imbibed, like our mother’s milk, the story of how Stalin told Togliatti to prevent any radical rupture in Italy since it was on the wrong side of the line decided with Churchill and Roosevelt at Yalta. At the same time, we all knew about the way the resistance liberated some key northern cities before the Allies arrived. We revelled in the stories of angry resistance fighters reluctant to hand over their guns and disband on the PCI orders.

As Broder shows, while there was anger and a willingness to fight it was very uneven – the rural south had mobilised very few partisans outside of Naples and the politically organised social base of the left was more limited than it appeared. It is an illusion to say a majority of the population unified around the resistance before the victory was secured.

Consequently, a simple binary picture of the masses in a state of insurrectionary fervour being blocked by the betrayal of the PCI just does not fit the facts. Of course, this does not justify the PCI’s reformist line nor invalidate the idea that more serious gains could have been made for working people to politically prepare the masses for a more radical strategy.

The MCd’I had its roots in earlier armed resistance to the rise of Mussolini and brought together Communists, anarchists and other activists who wanted to fight against the fascists. It developed in the poorest neighbourhoods of Rome. They were no large factories and although it had support among the tram workers it grouped together artisans and the precarious semi-proletariat. Its cadres and members were more working-class than the students and intellectuals which initially comprised the PCI organised resistance in Rome.

Under fascism and then the Nazi occupation there was extreme poverty in these areas, a large part of the comrades’ work was to organise actions, including illegal ones, to provide food supplies and other necessities. They took political education seriously and organised their own school. Most were self-taught and not graduates. Ironically the PCI explained their leftist deviations by some pseudo-Marxist verbiage about the lack of trade union organisation in these neighbourhoods and the social fragmentation that existed.

Looking back from how activists operate today under relatively democratic conditions it is hard to get our heads around how much working-class militants were able to organise their social base and put out a serious political publication. One important consideration also is the way they were cut off from knowledge about what was going on outside Rome. In fact, we see in the book how the PCI exiles coming back into Italy took some time to adapt and did not find it all that easy to convert their comrades to the correct line of national unity.

Looking back from how activists operate today under relatively democratic conditions it is hard to get our heads around how much working-class militants were able to organise their social base and put out a serious political publication.

The isolation of these groups meant that the PCI and the Bandera Rossa groups were both enthusiastic Stalinists. The MCd’I always saw themselves as an external faction of the PCI and looked forward to reunifying in a refounding conference. However, they took two diametrically different interpretations of what Stalin’s line really was.

The MCd’I, like all communists, saw the October revolution as the model: an inter-imperialist war leading to defeat of their bourgeoisie creating the conditions for a revolutionary seizure of power by the masses led by the Communist Party. They thought Stalin supported the same scenario in Italy. An extra element feeding this project was the news of the successes of the Red Army which would come down to Italy to seal the victory. A popular saying among all communists at the time was ‘ the moustached one is coming’ (Stalin was known as the Baffone).

As for the PCI, Togliatti arrived back in Italy after the Allies landing in 1943 and proclaimed the Salerno turn. This meant support for national unity including supporting the ex-fascist Badoglio government. The real line of Stalin was clear.

Even after Togliatti’s arrival the MCd’I still did not really believe that Stalin was in favour of such a line. It was seen as a clever bluff, the so-called doppiezza (double game). It was just a temporary tactic (like the Hitler/Stalin pact) that would be abandoned once the insurrection occurred. Indeed this belief in doppiezza was relatively strong inside the PCI. The leadership even cleverly and very vaguely hinted at a more militant approach in internal bulletins. Some socialists inside Labour have harboured similar illusions at various times – we will get into power and then real change will come!

The MCd’I represented real forces as shown by official figures suggesting in Rome they had 2548 militants against 2336 for the PCI. (see pp8 and 9) There was even a unity meeting which came to nothing. The PCI would not have participated in such a meeting if the MCd’I did not have some weight. Data about the repression back up this reality. Two hundred were deported to Germany and 186 were killed.

Why were the dissidents unable to mobilise their base and challenge the PCI leadership more effectively?

We can summarise the reasons explained in Broder’s work:

- They were hard hit by repression, losing some of their leading cadre. Their internal cell structure was looser than that of the PCI groups.

- When they eventually understood that Stalin decided on the Salerno turn it was a source of disorientation. Unlike the Spanish POUM they were never critical of Stalin and had a lot less information of Soviet reality. The POUM had interacted with Trotsky.

- It was rather hierarchical without much democracy which made it difficult to correct its errors

- It was limited to Rome and despite attempts after liberation it was not able to build bases elsewhere. They attended a left conference in Naples which included Trotskyists but their Stalinism made any unity impossible.

- PCI moved to isolate them through using their government positions to limit access to printing facilities. There were also smears that they divided the resistance, were Trotskyists or even objectively helping the Gestapo. Although not on the scale seen against the POUM in Spain there were some cases of violent elimination.

- Doppiezza – this illusion in a double strategy prevented them from developing a coherent alternative political strategy.

- Like they said about the generals in the Great War they were fighting the last revolution rather than working out a strategy for the Italian context. They applied the Soviet model too mechanically. Despite desperate calls there was no insurrection in Rome and they failed to draw any lessons from that. Perhaps some left groups in Britain today still think they are fighting the last revolution.

- Leadership splits over how to respond to the setback and to the PCI further weakened their capacity.

- Although the PCI deliberately exaggerated the incidence of common criminality and banditry in and around its ranks there was some evidence of this, which weakened it politically

- It is telling that despite producing political analysis regularly in Bandera Rossa, there was no serious political document after the war that tried to work out what had gone wrong. This indicates their certain political limits.

After the war and the failed attempt to build a national presence the activists either drifted out of politics or tried to rejoin the PCI. Of course, the party would only take in the ‘less’ extremist and none of the leading cadres.

Broder’s account also points to some debates on political tactics and strategy that have surfaced regularly on the left. For example, there is the question of armed struggle and how to use it. Attacks on Nazi troops led to the notorious reprisal policy of ten to one, the fascists would kill ten Italians for every Nazi killed. If you have limited resources and rely on your base in the population you have to assess very carefully what you do in these circumstances. The MCd’I did question some of the violent actions against Nazi troops that led to such reprisals. It wanted to maintain its forces for the coming insurrection. The GAP units of the PCI had a different view at the time. They believed that such actions could create confidence and force people to choose sides. As the writer discusses in the final section the Red Brigades had a similar sort of notion that armed actions would galvanise the population. Discussion about armed struggle and its relationship to a social base and overall political strategy was very important in Latin America in the 60s and 70s. Analogous tragic errors were made.

I would have liked a longer discussion in the final section about what was and was not possible in this period. What could a revolutionary current have done better at that time? While an insurrection was not possible what further action could have provided a base for further radical action in the post-war period?

This book is well worth a read and is a good resource for political education or discussion. David Broder writes accessibly for a non-academic audience. It definitely sparked my interest in finding out more about these dissident communists. We have very few photos but with this book, we can read their publications and leaflets. This book helps bring them back to life and respects their memory.

In the Monument to the Martyrs museum at the site of the Nazi murder of 335 anti-fascists at the Fosse Ardeatine caves near Rome there is a piece of paper bearing the last words of Tigrino Sabatini:

Don’t forget what we died for, don’t exploit our death.

Tigrino was a militant with the MCd’I. Both the PCI and most mainstream politicians insist that he died for Italy not for one side in a civil war. Tigrino himself certainly had a different view.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War