Why does the left need to talk more about sport?

“It is just a bread and circuses thing to keep working people alienated from an awareness of their exploitation and oppression”

“We should always support anyone who is playing against England, it’s revolutionary defeatism against our imperialism isn’t it?”

“The left should be working with English fans to develop a progressive sense of patriotism and identity”

“Soccer fans express the last residue of a working-class collective identity

“Sports discipline and represses our natural desires and pleasures that are disruptive of capitalist order”

“Sport just reproduces a capitalist ideology of competition, that anyone can achieve success if they work hard and a general machismo”

I have heard all these sorts of comments from people on the left. In this article, I want to show that these notions are all flawed. We need a more nuanced and balanced understanding of the contradictory role sport plays in today’s capitalism. It follows a presentation and discussion at a recent London ACR forum. It is a work in progress and I would welcome readers’ reactions to it. (editor – please use the join the discussion section at the bottom of the page)

Let’s face it, the average working person is generally more interested in sport than politics. Most people could not name many of Johnson’s cabinet or of Starmer’s opposition front bench for that matter. On the other hand, they could name most of the stars in the sports they follow and know a lot more about them than the politicians. Even those people we meet in campaigns, talks, and in meetings who are somewhat interested in politics are probably more engaged with sport than the average left activist.

Thankfully sport intersects with politics in many ways. Yesterday (2 September) there was the furore about the racist abuse the Hungarian fans unleashed against black England players in Budapest. So it is always possible to link political issues into a conversation about sports. I was playing golf the other day and the whole group started up a discussion about disability having seen various sports at the Paralympics. Gender and trans topics were also aired as a result of the Olympics coverage. Sport holds up a mirror to the way our society is run. We can show how the present model distorts the true potential of healthy, life-enhancing sport through class, gender, race, and disabling power relations. Indeed although the media and right-wing try to fence off sport from politics there has always been a close interaction. The famous black power salute at the 1968 Olympics or the role of the sports boycott to weaken the South African Apartheid regime are two notorious examples.

Commodification of sport

As capitalism has relentlessly brought commodity production and the market into nearly all types of human activity so sport is no longer just a private or local amateur activity but a huge part of the economy. Capitalist profits are generated increasingly in the service/leisure sector of the economy rather than in industrial production. More workers than ever are directly employed in sports-related businesses. You could argue that ideology and activity connected to sport has, to an extent, replaced the role of religion, which in earlier phases of capitalism integrated people into a shared narrative that reproduces the system. From childhood onwards, we participate in narratives or stories that make sense of our lives. Sports are a key part of that. Positive notions of individual effort/improvement, teamwork, role models to emulate, respectful competition co-exist with more negative ideas of winner takes all, excessive hero-worship, and win at all costs. Although a dominant narrative that reproduces the interests of corporate power and the national state prevails, the positive elements are never eliminated.

Developing a radical policy for sport

Just as the left puts forward policies about work, ownership, ecology, disability, gender, or countering racism, we need proposals on how to liberate the potential of sport. In the same way, we argue for mass accessibility and involvement in all forms of art, we take up what used to be an official slogan – ‘sport for all’. We also want resources for the local community to organise and manage all sports. There are contemporary examples of football clubs run cooperatively by fans, both here (Bath City) and in Europe (German clubs have to be 50% member-owned) and we should build on this. Already the tens of thousands of local sports clubs which are run almost completely by volunteers are a base on which to build an alternative vision of sports organisation. We are not just interested in team sports but all forms of individual exercise that improve health and well-being.

A particular emphasis should be on inclusion so it is much easier for women, minorities, and disabled people to participate. There needs to be a better balance between money given to the elite athletes and that which is spent at the grassroots. A lot of lottery money in the U.K goes to support elite sportspeople who attempt to bring back the medals from international competitions. The left inside and outside the Labour party should draw up a radical sports programme for a Labour government to implement. Any real change would have to challenge global corporate ownership, the TV subscription model, and the role of gambling companies both in terms of limiting and controlling their business and sponsorship of clubs.

Against a closed model of sport as an ideological state apparatus

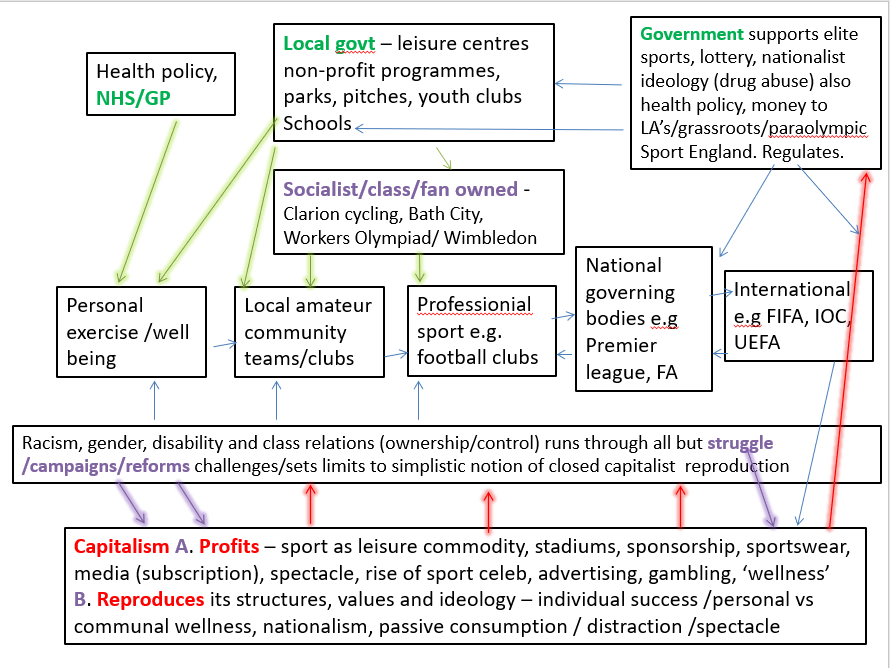

As I have tried to graphically express in a diagram below any reductionist, totalising, or closed ideological models fail to understand both the contradictions and class relations that disrupt capitalist domination as well as the positive elements of sport that continue to thrive. Certain readings of Althusser’s notion of ideological state apparatuses, tend to create a closed reproduction system that eliminates the relative autonomy of civil society from the state. Sports activity does not simply reproduce capitalist domination. For example, competitive sports are not the same as capitalist competition between companies. You are not pro-capitalist if you enjoy a competitive game of tennis or cricket. Similarly, support for your national team is not equivalent to the betrayal of the Second International in supporting national states such as in the First World War conflict. Reading the articles in Socialist Worker during the European football championships you got the impression that the reader was crossing class lines to support England at football.

Although fascists like the Nazis (1936 Olympics) or Mussolini’s party (Italian football) used sport to express their nations’ purity and strength, this is not comparable to Johnson’s bungled efforts to milk England’s Euros success or that of the GB medal-winning haul at the Olympics. There is little evidence that sporting success results in electoral benefit for the government of the day. Supporting your national team does not make you a racist, even if racists will attempt to make a bigger thing of it, including acts of violence against rival fans. A converse error is to search for and to construct some sort of progressive national identity via national sports teams by emphasising their multi-cultural, inclusive character. Obviously, it is great that our national teams represent the broad mix of society, but you can celebrate that without propagating the St George flag. In any case, the rise of Scotch or Welsh national consciousness makes any such effort even more contradictory.

How the relationship between sport and capitalism has changed

Historically professional football was anchored in local communities where clubs were owned by local businessmen with footballers paid within a maximum salary cap, well below that of a solicitor’s income. For some decades now football has been dominated by global corporate capital with players in the top divisions paid many times the average professional salary. When television started the coverage remained limited. Once subscription services like Sky started huge investment poured into the sport. Today the TV rights to the Premier League are sold for billions and it is transmitted throughout the world. Sponsorship and advertising followed the new TV coverage bringing in even more money. Consequently, top footballers became celebrities and were able to secure millionaire salaries. The relationship between local communities and their clubs has changed. Players used to come from the surrounding communities and still lived among them. Ticket prices have skyrocketed over the premiership era, pushing the game beyond the reach of many working-class supporters. Recently spontaneous mobilisations took place by fans (including those whose teams were going to be in the competition) against the European Super League. It would have set up a limited cartel of top clubs with no relegation. These mobilisations showed there is a residual element of collective identity with your team and a consciousness that corporate greed is ruining the game.

Average working time has decreased and leisure time increased so the time and resources people can spend following/consuming sports and, to a lesser extent playing, is greater. Leisure centres have mushroomed, run both by local councils and private businesses. There is a greater number of sportspeople who take part in a burgeoning exercise/wellness sector which includes activities like aerobics, yoga, or pilates. Although local team participation has declined – famously expressed in the title of a US book recording the decline of ten pin bowling leagues, Bowling Alone (Robert Puttman) – the wellness business is booming. A populace that is taking an interest in looking after their bodies and keeping fit is positive but all the attention seems to be on individual fulfillment, sometimes linked to the idea that this is a key to material success or finding/keeping a partner. There is also an element of fat-shaming and promoting a certain conventional or sexist body shape. Nevertheless, it is positive if schools, in particular, can offer more exercise or wellness activities rather than just the standard team sports.

At the 1968 Olympics, women’s athletics track events stopped at the 800 metres distance! Today women’s participation in sport is much more comprehensive. A big change has been the opportunity for women to make a career in sport. Bille Jean King, the US tennis champion, had to do it the hard way by setting up an autonomous women’s tour in opposition to the US tennis governing body. Today women tennis players have prize parity in the grand slam tournaments. There are now professional football leagues for women and although the salaries are inferior to the men’s game they have increased to the extent that you can become a full-time professional. During the war, women’s football was very popular as a spectator sport but it was all put back in the box by the football authorities when the men returned. Professional women’s sports like rugby, football, or boxing have helped to redefine gender perceptions, previously it was considered unfeminine to even think about playing these sports let alone making a career of them.

Gay sportspeople are now increasingly out and proud as we saw in the recent Olympics, one estimate put the LBGT medal tally at seventh in the table. There are still more difficult areas like professional football where it is rare for a top-flight male player to be openly gay. Publicly lesbian players such as Megan Rapinoe, from the US national team, are more prominent. A debate about the rights of trans people participating in sports is underway.

The experience of the English football team with a large number of players with a migrant heritage or BAME has shown how their intervention has helped the movement against racism and all discrimination. No other team in the Euros this summer so consistently took the knee before the matches. A comparison with the 1966 World Cup winning team is illustrative of the changes we have been highlighting. Young black footballers are better educated and more socially progressive. Their impact, partly as a result of social media, is much greater. The racist idea that English means white is demolished by how the England football team looks. Players like Rashford, Mings, or Sterling have taken on the Tories more effectively than Starmer and his team. One of the ceilings that need to be demolished is the access of black people to managerial or coaching posts. The disproportion between the percentage of black players in the top leagues and the number of black coaches is huge. Between 25% and 30% of pro-footballers in the four leagues are black but there are only two or three managers (Sports people’s Thinktank).

While such progressive changes show the potential of sport as an arena to challenge power in our society we can see how the win at all costs mentality – spurred on by the material rewards -is a negative counter tendency. Noami Osaka, the champion tennis player, withdrew from a grand slam event as a result of mental health concerns. Athletes have spoken up against sexual or physical abuse by male coaches. The victims saw the coach as a key to success so it is understandable how they can exploit their position of power to abuse their charges. Drug abuse, sometimes fostered by the state or deliberately ignored by national governing bodies is another plague on sport encouraged by both an an-achieve-at-all-costs mentality and state chauvinism.

Another big change has been the participation of disabled people in sports right up to the Olympic level. This week sees the final days of the Paralympics. There is full coverage on Channel 4 and the media report extensively on the games – predictably focussing on British medals. Indeed the current medals table shows Britain being only currently surpassed by China, this shows the degree of support that has been organised across many sports. The Paralympics only started out of Stoke Mandeville hospital in 1948 but the TV coverage here really took off with the 2012 London Olympics and support for it has increased ever since. For disabled activists, it is a double-edged sword since, on the one hand, it has increased the visibility and awareness of disabled people but at the same time can tend to focus on the heroic, exceptionality of certain disabled people overcoming all the odds stacked against them rather than really addressing how our society ‘disables’ people and fails to adequately provide the resources they need to manage their own lives. I asked leading disabled activist Bob Williams-Findlay to comment:

Most sports operates within contradictions — they give pleasure to participants but nonetheless comply with dominant ideologies. Paralympics were always part of the rehabilitation ideology whereby they began from the normalisation narrative — well-being and giving them a positive set of goals to strive for.

Dominant ideology constructs a duality whereby disabled people are either tragic or brave. Channel Four perpetuates the supercrip imagery for example. In recent years the Paralympics have fed into the neoliberal agenda as a result.

The philosophy also focuses upon functionality as the system to determine who can participate in which category. Despite all of this it does provide opportunities to do sport.

Bob Williams-Findlay

Some comments on the diagram above

The above diagram attempts to graphically express the main ideas I have discussed in this article. I have deliberately used blocks rather than a series of circles to get away from a simplistic reproduction model. Sport is not one undifferentiated entity but a series of interconnected practices and institutions. The arrows reflect conflicts, challenges, and influences. The red arrows show the noxious power of capital, the green ones show how government or local government, or other bodies can provide resources and support, the purple ones show challenge, struggle, and reforms. The foundation and most powerful influence is shown at the base, with capitalist social relations. It is important to understand this power in terms of both material practice (exploitation, economic activity) and ideology that in real life cannot really be separated. One could have put the state and government next to or alongside capitalist power but there is a relative autonomy of the state and politics from capital. Certainly, the strong red arrow towards the state, recognises it is a state that exists to maintain capitalism. The middle series of blocks try to represent the links between the individual desire for exercise and sport as fun and participation at the local, amateur, and professional levels. It is important also to maintain the contribution of alternative mass or working-class sports projects both historically and those that exist today.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Protest Review Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women