“In our case, the principle of internationalism is the only one possible… The whole work, called art, knows no borders or nations, only humanity.”

— Preface of the Blue Rider Almanac

The Importance of the Blue Rider Art Movement

The Blue Rider art movement was important for three reasons:

- Transnationalism: An earlier exhibition in 1937 focused on the group’s German roots. This show reasserts its internationalism.

- Role of Women: Women artists played crucial roles in leadership, organisation, and artwork production.

- Contemporary Issues: It tackled issues still relevant today, such as multiple identities, fluid sexuality, migratory experiences, ethnic intolerance, everyday chauvinism, war and its trauma, the environment, and our relationship with animals.

What Is Expressionism in Art?

Expressionism followed Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, movements particularly significant in France, exemplified by Monet and his water lilies. Expressionism emerged further east, with Russian and Germanic origins. Its characteristics include:

- Instantly recognisable bold, pure colours and dark outlines

- Dramatic forms and gestures

- Expressive distortion of forms

- Atonal music

- Free verse

- The angst of early silent cinema (Murnau, Fritz Lang, and films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari)

- Decadent tastes

- Medieval striving for the symbiosis of artistic forms (p.14, Tate catalogue)

The Impressionists certainly moved on from a rigid academic gaze, giving us great art by rendering the outdoors and people in new ways. On the other hand, the Expressionists always feel more disruptive, modern, and radical. They broke more rules and asked more questions. The Blue Rider group exemplified this.

The Emergence of the Blue Rider

The group emerged in Munich at the turn of the century, which provided a relatively liberal and progressive environment for creatives. Misfits and marginalised individuals from less tolerant societies ended up there: artists with Jewish ancestry like Elisabeth Epstein, from the declining Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, those like Kandinsky or Maria Franck-Marc, who could not fit into their privileged milieu, and those who pursued unconventional relationships like Marianne Werefkin or Jawlensky (p.14, ibid). Paul Klee from Switzerland, the composer Schönberg from Austria, and the Delaunays from France were all in Munich.

Kandinsky remembered in 1930 the importance of the bohemian neighbourhood of Schwabing, just north of the centre of Munich: “(It was a place) where everyone painted…or wrote poetry or played music, or learned to dance.” Certain localities are the nurseries for new thinking and ideas. The idyllic rural surroundings of Murnau were also important, and the exhibition shows several pictures depicting this area.

The Split from NKVM and the Iconic Yearbook

As is often the case, the Blue Rider group formed after a split from the NKVM (New Munich Artists’ Association), which had rejected one of Kandinsky’s abstract pictures for an exhibition. The new group was established in 1911 and held two exhibitions with hundreds of works from over 30 artists. Only three women artists, Münter, Epstein, and Goncharova, were in the show. The famous Blue Rider yearbook, which you can see up close in the exhibition, was published in 1912.

“Works by both Western and non-Western artists were represented, which was unusual and new.”

This iconic book was experimental, avant-garde, and non-hierarchical. It represented works by both Western and non-Western artists, which was unusual and new. It aimed to produce a new synthesis of the arts while celebrating the principles of total abstraction and total realism. The book encouraged closer collaboration between the visual arts and music, theatre, vernacular art forms, children’s art, and non-Western traditions. While some women’s art was illustrated, all the commentary was written by men. Non-Western art was anonymous and often cropped in the book, unlike the Western artists. Thus, the relationship of these artists to the East or colonised world remained problematic. The links and affinities between a Van Gogh and Japanese art were hinted at but not fully developed. However, nothing as radical as this collective work had been seen before in the art world. A second yearbook was never produced, and the collective dissolved at the outbreak of the First World War.

Rediscovering Overlooked Artists

This exhibition highlights some of the artists, including women, who have traditionally been overshadowed by the way art history has foregrounded Kandinsky’s role. Marianne Werefkin played a pivotal role — she was dubbed the “Baroness” by other artists as she coordinated and led the weekly salon in Munich. Her journals prove she was even ahead of Kandinsky in formulating Expressionist ideas.

“Her journals prove she was even ahead of Kandinsky in formulating Expressionist ideas.”

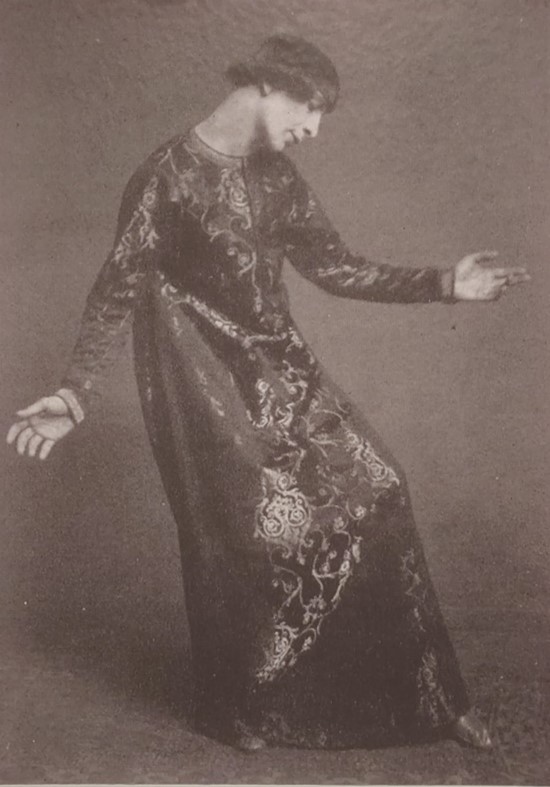

One of the most interesting sections in the show is how her work engaged with gender fluidity. She consciously took on the concept of the “third sex” proposed by sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld in 1904 and identified with the term Mannweib or man-woman (a term commonly used to disrespect women artists). Marianne aimed to unify feminine and male elements to achieve the androgyne (p.92, catalogue). You can see this in her striking self-portrait, where she referred to herself as catching “the male gaze that call for a slap.” In her diary, she wrote: “I am not man, I am not woman, I am myself.”

Werefkin also painted the dancer Sacharoff, who pioneered gender-fluid performance:

Apart from highlighting Werefkin’s importance, there are plenty of other pictures to enjoy in this exhibition. There is also a section that shows how Kandinsky and Schönberg collaborated to combine music and painting.

Notable Artworks in the Exhibition

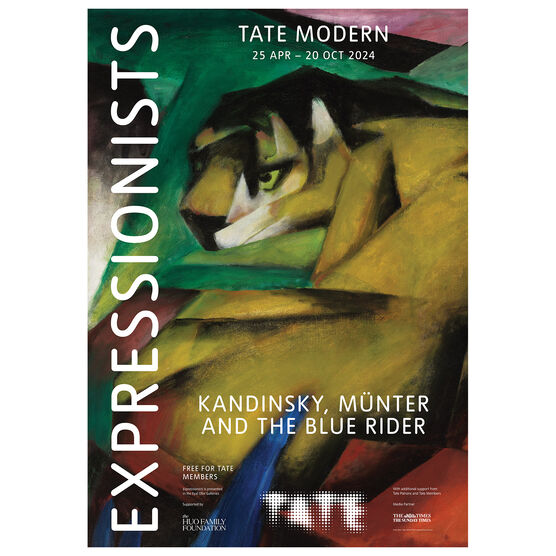

I particularly like this painting of a tiger by Franz Marc. He was interested in spirituality and eastern religions, as well as studying Japanese prints. The cubist blocks, vibrant yellows, reds, and spiral composition convey the uncoiled energy of the tiger. Power and menace leap out of its eyes. This expresses what you may feel when you see such a beast; it does not attempt to recreate a natural impression of it. Unsurprisingly, this was chosen as one of the cameo pictures of the exhibition. Marc was killed at Verdun in 1916.

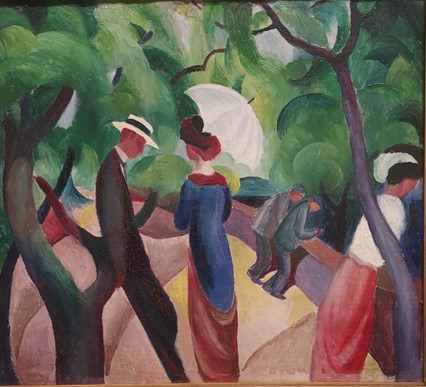

There are lots of beautiful Kandinsky pictures in the exhibition, but we are so familiar with them that I have selected a lesser-known artist for my final picture. A joyful celebration of everyday life, this is entitled The Promenade. Again, it is interesting to compare this non-naturalistic depiction with many well-known Impressionist pictures of scenes of people in the park. Here, there is no recognisable detail or precise brushwork rendering the complex impressions of light, colour, and shade. Yet, we still feel the sense of being outdoors, people enjoying themselves amid the circles of greenery and winding paths. The picture has its own movement, life, and music. Here is what he said about his painting: “Work for me means a thorough enjoyment of nature, the blazing sun and trees, shrubs, human beings, animals, plants and pots, tables, chairs, mountains, water of illuminated becoming, I immerse myself in the snow-drops’ friendly nodding, in the rhythm of the bird-laden twig swaying in the sun.” Macke died in 1914 on the Western Front.

This show opens up another path to understanding the Expressionists. You will see some classics from Kandinsky, but there is a lot else to see too. The exhibition demonstrates how new art movements are formed from the material culture of the time, based in certain places and interpreted through multiple friendships and relationships. It tells the story of a radical art movement that cast a long shadow over modern art.

“It tells the story of a radical art movement that cast a long shadow over modern art.”

Expressionists – Kandinsky, Münter, and the Blue Rider is on at the Tate Modern until 20th October.

Art (53) Book Review (121) Books (114) Capitalism (65) China (79) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) Economics (40) EcoSocialism (55) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (56) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (69) Gaza (59) Imperialism (97) Israel (119) Italy (45) Keir Starmer (52) Labour Party (110) Long Read (42) Marxism (47) Palestine (164) pandemic (78) Protest (151) Russia (339) Solidarity (140) Statement (48) Trade Unionism (139) Ukraine (344) United States of America (132) War (367)