AI does not put people out of work. People put people out of work.

The article begins with a look at the Luddite phenomenon and explores how this might help us understand the social implications of Artificial Intelligence.

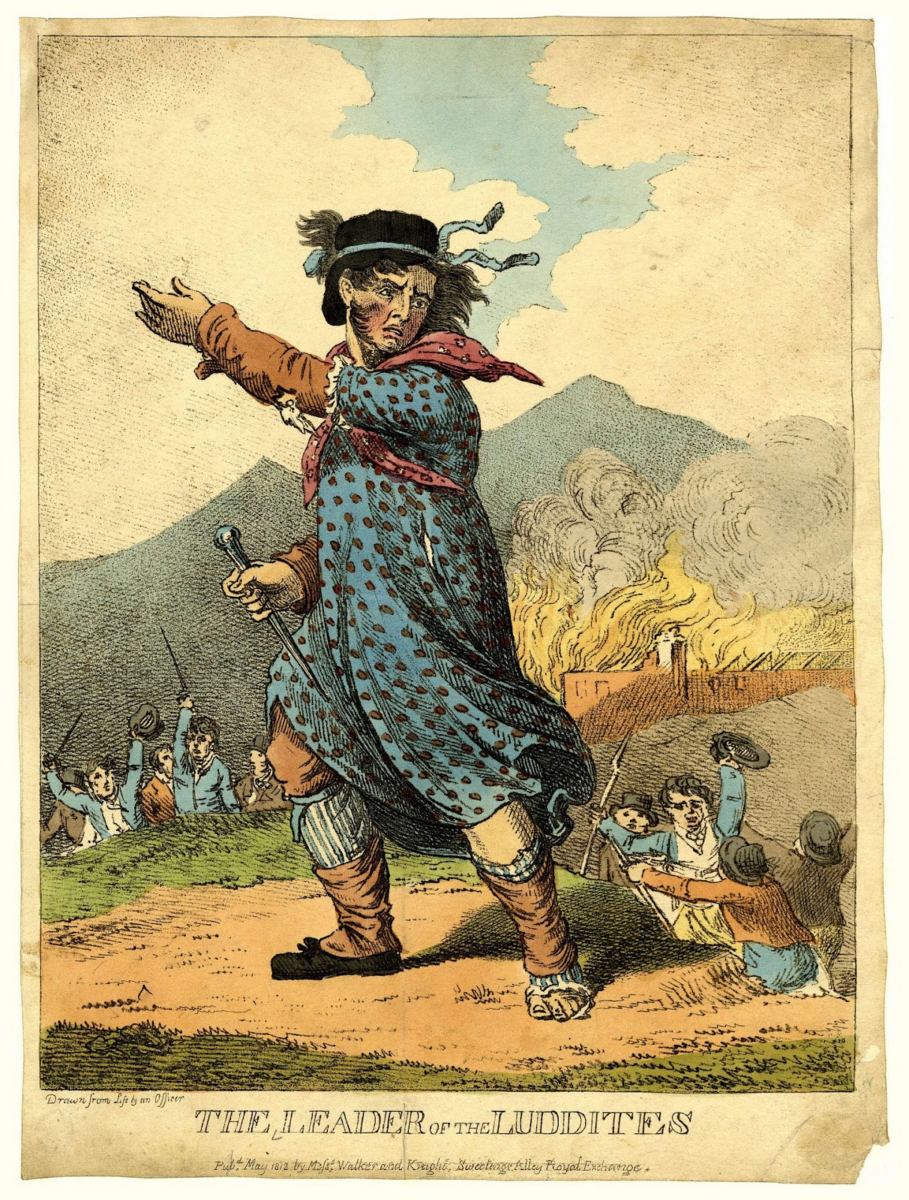

The Slander of History

One consequence of ‘national education’ is how it crushes folk memories under the weight of so much standardization. I grew up in the English Midlands, in a place where 200 years previously, the movement that came to be known as Luddism sprung up. Luddism was a social movement of the 1810s in Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, and Leicester, one quickly snuffed out by state violence. Yet, we were never taught much about who the Luddites were, just a memory of visiting the Framework Knitters Museum and being entranced by the hypnotic motion of the circular sock knitter.

Like most people from my generation, the word ‘Luddite’ was simply a synonym for someone who hated new technology. I probably heard it used to describe people who refused to get a mobile phone, or who persisted with handwritten letters well into the age of email. If I thought about who the Luddites were, I imagined them as a quasi-religious sect that held primitive views against the inevitable march of technological progress and smashed up weaving equipment in a frenzy. Maybe you had, or have, the same view.

Actually, far from an irrational cult, the Luddites were a highly organised group of working weavers and their supporters. Did they smash up looms? Sure, but it wasn’t because they hated some abstract idea of technology. The fury of the Luddite movement, which spread over the East Midlands and Yorkshire areas, was centred around the social relationship of clothing workers to their work.

For frame-work knitters in particular, their livelihoods were not only being ground down by the introduction of machinery that would improve productivity (i.e. profits to the owners) but the practice of speculators investing in frames that could be rented out to the labourers. Thus, immiseration came from both a reduction in the cost of goods and increased rental costs for the frames. New technology made the manufacture of goods like stockings quicker, but this quicker process also led to poorer quality goods, an indignity that not only dragged down wages, but offended the worker’s pride in their craft.

Luddism manifested in the towns surrounding the city of Nottingham as a highly organised group of workers-cum-political activists, who carried out clandestine raids on workshops. Frame-breaking was not only illegal, but brought either transportation (i.e. exiled to Australia) or worse, execution, and 17 men were executed in 1813 for their participation in frame breaking. Thus, apart from their representatives in the media or local politics, the Luddite ‘Army of Redressers’ was an anonymous one, complete with a leader, “Ned Ludd”, a mythological figure who doubled-up as a pseudonym for various leaders of the movement.

Nottinghamshire’s other legendary figure of the redress, Robin Hood, is a celebrated figure whose name has been used to sell countless books and movies, as well as airports and energy companies. Hood’s tale is easy to grasp: rob from the rich and give to the poor. Ned Ludd’s cause: smash the machines that are used to justify our impoverishment, is less easy to script into a Disney film. In comparison to the somewhat paternalistic gentleman thief Hood, Ludd also perhaps represented the ‘sturdy self-reliance of a community’.

Go into Nottingham city today and between the cat café and a comic book shop, you’ll see The Ned Ludd pub. Beyond these small puddles of folk memory, Ludd is largely forgotten, and the Luddites are remembered only for what they did and not why.

History’s slander is a continual rebuttal to righteous protests. In 1998, a group called the Earth Liberation Front burned down a ski lift in the Colorado Rockies in protest against encroachment into the territory of the reintroduced wild Lynx. The actions were taken against property but the group were nevertheless dubbed ecoterrorists, a phrase that calls to mind violence against people. The waves of protest against free trade regimes and supply chains founded on sweatshops and impoverished farmers were, by a supine mainstream press, called “anti-globalisation”, a phrase that invokes once again the Luddite slander: a group of a primitives vainly standing against the tides of human progress. The actual lodestar phrase of those protests was “Another World is Possible”, an ideological riposte to the neoliberal “There is No Alternative”. The alter-globalisation protests at the turn of this century were not against new communications technology, but the ways in which multi-national corporations were using it to aid their ruthless exploitation of the world’s poor.

The Luddites were, in the phrase of Historian Eric Hobsbawm, a “collective bargaining by riot”. If one wishes to follow the spirit, if not the precise tactics, of the Luddites, the lesson is that social movements do not emerge prefiguratively from a grand plan, but from the bottom up. In his book Breaking Things At Work, Gavin Mueller argues that Luddism is not a political party but a “diffuse sensibility that nevertheless constitutes a significant antagonism to the way that capitalism operates.” We could perhaps go further and extend the definition of this sensibility to one that exhausts all avenues of antagonism, legal and illegal. The Luddites did not just break frames, but also attempted to lobby for political intervention through government channels. Add to this a prohibition of violence against human bodies, a code of conduct and principle, that comes from community, not state, law. The Luddites were a secret society but not an escapist one.

Mueller identifies strands of Luddism in the political/theoretical degrowth movement, and also in the Maintainers, a social phenomenon built around repair and renewing current technology rather than endless innovation. He also identifies cultures of illegalism (for instance farmers sharing hacks that allow their tractor software to run) as a “a ripping-open of the walled gardens of code.”

Artificial Inevitability

How then might Luddism apply to Artificial Intelligence (AI) and are there ways in which diffusely located antagonisms towards its exploitative social forms emanating from it could be knitted together?

In the past year AI software, most notably Chat-GPT in terms of Large Language Models and Dall-E and Mid-Journey for images and various other programs for voice modelling, has reached a point where its output is close to passing the Turing Test, in other words, indistinguishable from humans.

I say almost, because as someone who has used Chat-GPT, it is far from a finished product, and claims of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), the presumed state of technology where systems are more intelligent than humans, still seems a long way off.

I will also make it clear that none of my political articles on ExMultitude have or will ever use Chat-GPT or other Language Modelling software. My intention here (and the reason I don’t send out an article a week) is to write carefully and precisely, and to connect with you beautiful readers on a human level. (I may use spellcheck, though.) In my work as a copywriter, I have found ChatGPT useful as a sounding board for ideas, for example feeding it a sentence and asking it for five suggestions on how to make it nicer, from which I select and edit. However, anyone who uses it to produce full copy will be putting out some pretty terrible, and potentially misleading information. The theory of the ‘dead internet’ is that so much of what we read online feels like content for the sake of content, and LLMs will only intensify this. In terms of work, AI style programs will shakeup labour markets, especially in industries that work with text, and even things like software coding and programming will see job losses.

However, we must be clear that this is not a case of ‘robots replacing humans’. AI does not show up at your workplace with a zinc-coated name tag and a manager saying, “Everyone, this is your new colleague RobbieV2, who’ll be working for us without pay. I’m sure you’ll all do your best to make him feel welcome.” Instead, AI provides the conditions for a reorganisation of labour. One person will now do the work that previously six people performed. In capitalist societies this means that, yes the outcome is that people will lose their jobs, but it is not AI that is the active force in this re-arrangement.

Economics dresses itself in the language of inevitability, but there is nothing inevitable that says labour-saving technology must equal job losses. Did societies of ancient humans, arriving on a new, firmer, style of knot for foraging baskets, lament that, with the additional carrying ability these baskets provided, some members of the tribe would now go hungry? Or did these increases in productivity allow them more time for other innovations, for leisure, art, and culture?

A process: X workers make Y product in Z hours. The introduction of a new productive technology into this process could mean that we reduce Z, the working day. In a capitalist society, one in which many different companies compete, doing this would put a company at a disadvantage, at least in terms of price, in the market. Thus, the introduction of new productive technologies allows capitalists to reduce X, the number of workers it takes to make Y product.

AI doesn’t put people out of work, people put people out of work.

The Luddites understood this. That is why, alongside sabotage, they wrote letters and petitions to parliament asking them for legal protection against capitalist speculators. So where then are our contemporary Luddites of the digital age?

No sooner had Chat-GPT launched then people were scheming to break it. The ‘Do Anything Now’ (DAN) command used the rules of language to jailbreak Chat-GPT and go beyond the limitations of the language and content rules its creators installed. Undoubtedly, much of the motivation to hack ChatGPT has come from reactionary and infantile motivations; a sort of alt-right version of making the calculator say 80085.

It’s difficult to imagine such hacks having the potential to coalesce into full political organisation on behalf of workers. Instead the racism of idiots only plays into the capitalist script of a divided workforce. Luddism may be somewhat disparate and at odds with the ‘party’ model of organising, but that does not mean that all reactions or sabotage belong under its banner.

Perhaps the intentions of the creators will be enough? In February. OpenAI, the company behind Chat-GPT, released a manifesto on the future of AI. In short, a thinkpiece of techno-optimism shrouded in the language of caution and reassurance as humanity presumably marches on to meet its destiny in the form of AGI. Employing words like democracy, decentralisation and a desire for AGI to be “an ‘amplifier of humanity’, the article uses the sort of language that will reassure liberals who in the past year have grown tired of the bombast and arrogance of other technocratic highchiefs like Elon Musk.

Yet OpenAI better than anyone should know that language alone does not guarantee ethics. “We want the benefits of, access to, and governance of AGI to be widely and fairly shared”, says Sam Altman of OpenAI, while at the same time partnering with an advertising agency representing Coca Cola, a company alleged to be complicit in numerous human rights abuses. You will not find anything in the carefully crafted press release that suggests that there will soon be less jobs available in the marketing department, but when companies speak of “efficiency” and “productivity”, these are normally euphemisms for reducing the costs of human labour.

AI implementation for productivity and labour reduction is not the only antagonism. The Coca Cola statement mentions use in Human Resources departments. AI as a means of labour control is another battleground that tomorrow’s Luddites must engage with. AI systems are not just able to write like humans, but in terms of data processing go well beyond human capabilities.

During pandemic lockdowns, with exams unable to be taken, there was plenty of rumbling about using AI to predict student grades. The next logical step to this is to implement AI to pre-screen job applicants and employees, buying up cookie and social media data and via a series of arcane algorithms, assigning each individual a number. From there we may as well move functionally to the world of the 2002 film Minority Report, where ‘precogs’ tell the police who to arrest based on psychic prediction, except with massive algorithms instead of superhuman powers.

Even if the vision of AI-controlled everything does not instinctively give you the chills, then consider that anyone who has ever used AI will tell you: it is not and never will be accurate. Only a fool would simply take text generated by AI and put it out there into the world as is. Perhaps this does not matter when it comes to trivial stuff like marketing, but when dealing with life-changing stuff like the ability to get a job or not be selected as a potential criminal, do not want to talk to a real person when we find ourselves victim of an accounting error? Worker resistance against AI regimes thus needs to target the companies that work with AI as well as the AI companies. A recent report by the European Trade Union Institute (EITU) is actually quite impressive in its scope of proposed AI regulation. Among the proposals are regulations on worker surveillance, algorithmic transparency, and a ‘right to explanation’ for workers when it comes to automated decisions.

These are all positive and in many cases pre-emptive proposals, and trade unions should start to unite around them. Simultaneously, however, legislation about the ethical use of AI in the workplace cannot by itself account for capitalism’s larger shadow of constantly seeking to reduce labour costs by any means necessary. Protecting workers against automated management decisions will not in itself prevent layoffs due to ‘efficiency gains’ of new AI, or indeed any technology, for this is the baked-in logic of capitalism, almost the same as it was 200 years ago.

Capital’s managers will claim these ‘efficiency’ boosts are necessary. Equally inevitable will be the sabotage. Whether it succeeds this time is anyone’s guess.

You can subscribe to their blog here ExMultitude.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Review Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women

A few thoughts…We now live in a Climate Emergency…any form of technology needs to be seen in this context as to whether it actually helps or hinders, whether it helps improves the situation or actually makes it worse.

Technology as such is not necessarily a problem though of course it depends on what the technology is and for what it is used ie Is the development of Nuclear power and Nuclear weapons beneficial to humanity’s happiness,individual and collective and Global security,health and safety ?

I would say NO ! Never was and never will be for numerous well founded reasons I wont bother going into here.For those that have eyes to see..

Has Alexa and her mates really improved people’s lives ?

I hate Alexa. I just dont understand why people want her/it in their houses, in their lives. People now site Alexa in divorce cases saying their respective partners spend more time with Alexa etc etc

Do we want to end up paying for everything we buy by either buying everything online or by scanning an app on a smart phone or by scanning a watch or by a microchip inserted into our wrist or eyeball ? Star wars ? Cyber warfare ? Rockets to Mars ? The list is endless.

We are being saturated by this stuff all in the name of ‘change’ and ‘progress’

Driverless trains,planes,cranes and cars is BONKERS

Souless Rail and tube stations with out ticket offices or staff, no toilets or waiting rooms,trains without any staff,little or no health and safety all in the mane of ‘modernisation, ‘change’ and ‘reform’,increasingly NO QUIET ZONE CARRIAGES, just carriages full of thoroughly bored and boring zombioid humanoids increasingly detached from reality spending hours upon hours upon hours on their phones talking utterly meaningless shite in to thin air.

At present under Capitalism We dont have any control of any of this other than to engage or not engage.

Have we necessarily advanced in terms of humanity and human to human communication ? (Remember talking to a stranger and enjoying the experience ?..how do we meet ?)

Fahrenheit 451

Are human beings any happier now living under an increasingly technologised form of Capitalism with the massive advance and spread in AI, computer software, mobile phones, smart phones, self service tills,utterly souless / staffless shops (apart from Security people and people who fill the shelves for now) presently being piloted in Britain by corporations such as Amazon with it’s ‘checkout less free store’ in Ealing and Notting Hill and Aldi’s ‘just walk out store’ in Greenwich,all situated in mainly wealthy ‘gentrified’ middle class islands surrounded by predominantly working Class areas.

We are becoming ADDICTED to tech and depressed by it too !

The main issue which seems to get slightly lost in this article is who is in control of the means of production and development of technology and who is determining the speed, the scale and spread of the consumption and use of technology ?

Where is the democratic accountability ? Technological surveillance.

Apparently Britain has more CCTV cameras on our streets per head of population than anywhere else !! Did we have any say in this ? None whatsoever !!

How accountable are the likes of Big Tech such as Facebook, tiktok, Amazon, Twitter and The military Industrial technological Complex ?

Strikes for improved working conditions and better pay (not peanuts)and sustained campaigns for trade union recruitment and recognition are vital for starters within such virulently anti-Trade Union Corporations.

Similarly, challenging inhumane working conditions eg in Poultry Factories where workers work on ongoing speeded-up production lines(it was ever thus) where they are not allowed to take toilet breaks so have to wear NAPPIES underneath their work clothes

Multi billionaire Capitalists such as Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg,The Global military Industrial-Technological Complex ? No thanks !

TIME TO THROW A SPANNER IN THE WORKS in a million and one ways before it’s too late !

Anyway,spending far too much time staring at a computer screen is really bad for your eyes and eyesight, your back and posture and your head.

It’s in The MaxHeadROOM !

Not to mention anti social media and cyber bullying