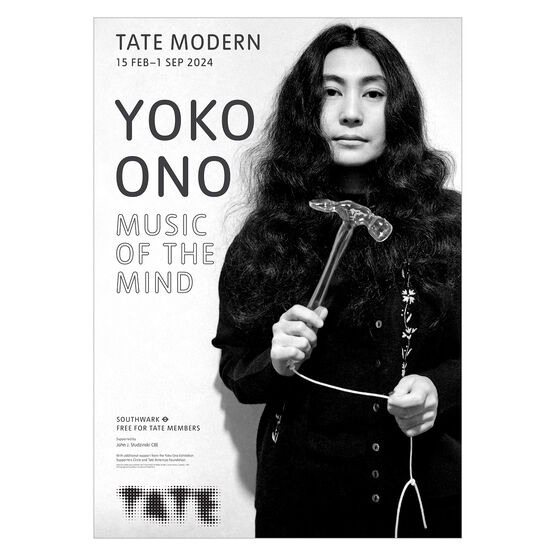

Like many of my generation, I first became aware of Yoko Ono through her relationship with John Lennon. This exhibition includes a section on their collaborative art, such as the “War is Over” bed-in in 1968 and their work with the Plastic Ono Band. However, it establishes that Yoko Ono was already a groundbreaking, multi-media artist long before she met John. Since Lennon’s death in 1980, she has continued to be artistically productive, featuring in exhibitions worldwide. Far from being an ‘interference’ in the Beatles’ artistic trajectory, as Paul McCartney once claimed, Yoko positively influenced Lennon, expanding his artistic creativity. One could argue that her art was somewhat held back by her relationship with John. Before his death, Lennon belatedly acknowledged Yoko’s significant influence on one of his most famous legacy songs, Imagine.

Many on the radical left welcomed Lennon’s alignment with the anti-imperialist, anti-Vietnam War movement. He was famously photographed holding a copy of Red Mole and was friendly with International Marxist Group leaders Tariq Ali and Robin Blackburn1. Many regretted his shift towards an idealist, pacifist position after meeting Yoko.

However, this exhibition shows that Yoko combined her pacifism with an understanding of imperialism, an internationalist perspective, a critique of the capitalist commodification of everyday life, active feminism, and practical solidarity with migrants and refugees. She may have focused on changing individual consciousness, but she skillfully manipulated the mass media and used her work to reach the general public. Far from destroying the Beatles myth, she succeeded, at least for a while, in building a bridge between avant-garde ideas and pop music.

Yoko also showed incredible dignity and resilience in the face of the barely disguised racism of the mass media at the time. She was the weirdo, Japanese, older woman taking away ‘our John’—a member of a group that had become a national treasure. The media ignored her credentials as an accomplished artist who had worked with modernist composer John Cage and the Fluxus group in New York and had been a prominent figure in the 1960s London art scene. She was one of only two women involved in the 1966 Destruction in Art Symposium, part-organised by leading Nuclear Disarmament campaigner Gustav Metzger. Lennon famously met her while participating in one of her art installations involving a ladder.

Here are some examples of her conceptual, participatory art featured in the exhibition:

Example 1: Put Your Shadows Together Until They Become One. A light shines so you can trace your shadows on a whiteboard. All the tracings mix together.

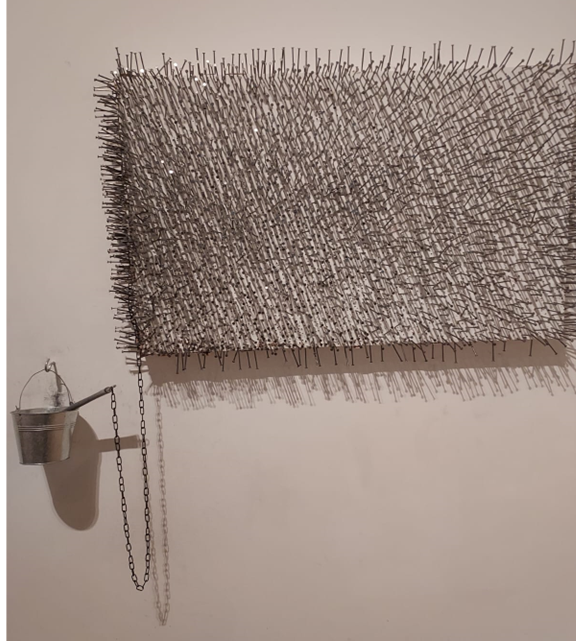

Example 2: Painting to Hammer a Nail. You are invited to hammer a nail into the board. You can also wrap one of your hairs around your nail. When the board is covered with nails, the painting is finished.

Other examples from the show include:

- A canvas in the centre of the room with a hole in it. You put your hand in the hole to shake someone else’s hand.

- A chess game played only with white pieces, symbolising the rejection of conflict.

- A bag you can enter and close yourself inside.

When you come to a Yoko Ono show, you are not there to view protected objects or pictures. You come to participate. You are encouraged to imagine through Yoko’s pithy ‘instructions or scores’. You experience making or completing a work and, through this, gain heightened awareness of simple everyday gestures. Yoko wants us to free our imaginations to confront both ourselves and society. Within this democratic dialogue, she aims to make the world a better place. For her, art is unfinished, a process in which we participate as collaborative creators. The foreword to the Tate catalogue sums it up:

“Instructions open to interpretation by anyone and everyone, guide visitors on their journey through this exhibition. We are invited to step on a painting, water a canvas, perform inside a bag, greet visitors by shaking hands anonymously, put our shadows together, hammer a nail, or play a game of chess, to celebrate our mothers, to share our hopes, dreams, and wishes, most importantly, to imagine” (p. 14).

Yoko is a versatile multi-media artist. You can listen to or watch her musical performances, see several films, installations, texts, drawings, a few painted pictures, objects, and recorded performances. There are no traditional paintings of people or landscapes or complex technical work. Her palette is limited, favouring white and blues, the colours of peace and the sky.

Unlike some world-famous artists, her work as objects to be collected does not command high prices. In a sense, her work challenges the commodification of art. This is documented by her parody of the art world, such as mounting a fake exhibition in a major New York museum or selling ‘catalogued’ pieces of broken glass linked to different mornings in her life.

Ono’s brief text instructions have been compared to traditional Japanese practices, like seventeen-syllable haiku poems and terse koan riddles given to disciples by their Zen masters. She wants you to read the instruction and complete the work in the music of your mind. Here are a few I liked, published in the classic 1964 art book Grapefruit:

Cloud Piece

“Imagine the clouds dripping

Dig a hole in your garden to put it in”

Voice Piece for Soprano

“Scream

- Against the wind

- Against the wall

- Against the sky” (1961)

Smell Piece

“Send the smell of the moon” (1953)

Wood Piece

“To David Tudor

Use a piece of wood

Make different sounds by the different angles of your hand in hitting it (a)

Make different sounds by hitting different parts of it (b)” (1963)

Yoko explains her art like this:

“The only sound that exists for me is the sound of the mind. My works are only to induce music of the mind in people… in the mind world, things spread out and go beyond time. There is a wind that never dies.”

But it is not pure individualism:

“A dream you dream alone is only a dream.

A dream you dream together is reality.”

She is also on the side of progressive people:

“I like to fight the establishment by using methods that are so far removed from establishment-type thinking that the establishment doesn’t know how to respond…The job of an artist is not to destroy but to change the value of things.”

One exhibit, Cut Piece (1964), is recorded on film for this show. She sits on stage and invites the audience to come forward and cut pieces of her clothes from her body. It is now recognised as a pivotal early work in feminist art history. When she performed it again in 2003, she said she did it ‘against ageism, against racism, against sexism, and against violence.’ Another film shows a naked woman with a fly, challenging the societal objectification and mistreatment of women. Later in her Plastic Ono Band albums, she created several feminist anthems, such as Sisters, O Sisters and Women Power. Her Arising album featured testimonials of women who have suffered harm. You can listen to them all in the show.

One room in the exhibition started with a small white boat set in the middle of a white floor and walls. Visitors were encouraged to take a blue pen and draw or write whatever they wished on the boat, floor, or walls. Yoko shows her solidarity with migrants and refugees in this exhibit.

Another exhibit reflects her pacifism. She hangs Second World War helmets from the ceiling. In one of the helmets, there are jigsaw pieces that, when assembled, form an image of the sky. When she was evacuated from Tokyo due to Allied bombing, she and her brother found solace by looking up at the sky through the roof. Local children had not been particularly friendly to these Tokyo evacuees. Throughout her artistic life, Yoko has used the colour blue and the sky as unifying global symbols. She hoped that making the puzzle whole symbolised the possibility of remaking humanity after the fragmentation of war.

“Take a piece of sky. Know that we are all part of each other.”

Socialists should always respect pacifists. Given that many wars are imperialist, pacifists can be important allies in the anti-imperialist movement. This proved true with the ultimate successes of the Anti-Vietnam War movement and can also strengthen the movement of solidarity with Palestine today.

This exhibition is well worth a visit. It truly feeds the music of your mind. The last image you see exiting the show is Yoko, well into her eighties, performing live at the Sydney Opera House. Watching that, let no one ever tell you her art was gimmicky or lightweight.

Ono invites you to take a piece of the sky, which she sees as a hopeful symbol of limitless imagination. The pieces are presented in German army helmets from the Second World War, referencing the violent fragmentation of hope through war. Despite being dispersed, the puzzle pieces are still designed to come together and reform the sky. They suggest the possibility of healing through collective action or thought.

Footnotes

- John Lennon was Interviewed at his home in Tittenhurst Ascot by Tariq Ali and Robert Blackburn of the International Marxist Group. A part of the interview was released in The Red Mole. Footage can be seen in the Apple TV documentary series 1971: The year that music changed everything. ↩︎

Art (54) Book Review (127) Books (114) Campism (31) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (45) Creeping Fascism (37) Economics (41) EcoSocialism (58) Elections (83) Europe (46) Far-Right (34) Fascism (61) Film (49) Film Review (68) Fourth International (32) France (72) Gaza (62) History (42) Imperialism (100) Iran (31) Israel (129) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (56) Labour Party (114) Long Read (42) Marxism (50) Marxist Theory (48) Migrants (34) Palestine (178) pandemic (78) Police (31) Protest (154) Russia (341) Solidarity (146) Statement (49) Trade Unionism (142) Trans*Mission (31) Ukraine (349) United States of America (134) War (368)