As you enter the exhibition the artist has displayed a series of questions that aim to involve you actively in the show. This work has not been produced as a passive diversion or entertainment to make you feel culturally in tune with the latest artistic fashion. It is not meant to soothe, make you bathe in some fine aesthetic or make you feel relaxed or comfortable Himid does not address us as isolated individuals but as people in socialised relations. She wants her work to have a consequence, an effect after you have left the museum. Her art is the opposite of the coolness, repetitive gimmicks and conspicuous consumption of artists like Damian Hirst or Jeff Koons.

What will I learn about myself here

What would I do in this situation

How is my life the same as this one

(,,,) What do I want to say

Who could I work with

What would a sharing of space mean

(…) What do I really want

Is this enough

How much time do I need,

What difference can I make

What is astonishing about the exhibition is the variety and diversity of the work on display. There are ceramics referencing the slave trade and Liverpool, several sound installations using music and spoken languages, cardboard cut-outs installations, paintings, textiles, sculpted objects, a decorated wagon and illuminated texts. Her training as a stage designer helps make this into a real multi-media spectacle. The catalogue suggests she wants you to experience it as an opera. The cuts out appear in a group as if characters on a stage that encircles you.

Himid is another black artist whose brilliance has only been recognised more widely since she won the Turner prize in 2017, the biggest art award in the UK. It followed more than 30 years of bold and witty work that puts people of African descent at the centre of our shared cultural history, which they’ve often been left out of. She played a vital and vocal role in the British Black Arts Movement of the1980 as part of a network of female artists of colour – alongside Sutapa Biswas, Sonia Boyce, Claudette Johnson, Ingrid Pollard, Veronica Ryan and Maud Sulter and others. The progressive and feminist curatorship of the Tate Modern has contributed to her earning this major retrospective

…

Lubaina Himid was born in Zanzibar, Tanzania in 1954 and moved with her mother to London when she was just four months old. Her mother was a textile designer, and she spent a lot of her childhood thinking about fabric… Throughout her practice, there’s real attention to what people are wearing. As a child, Himid frequently visited art galleries and museums. Her work has been in conversation with art history throughout her career.

As we have seen in our recent review of Kehinde Wiley on this website some Black artists have deconstructed well-known pictures of the art history canon in order to highlight the absence or the very limited colonial view of black people. In this exhibition, we can see the cuts outs referencing Hogarth’s famous Marriage a la Mode – Toilette. Himid places her characters in the London art world of the 80s:

London in the 1980s in the midst of the hedonistic, greedy, self-serving, go-getting opportunistic mayhem was a fabulous location for me as a satirist and wit. Everyone who shook or moved in artistic semi-circles or political whirlpools was a deserving dartboard. I took aim and threw. Hogarth…proved to be the perfect ally.

Lubaina Himid – from Tate website

Below you can see a detail where the young girl in her ‘remake’ has a collection of black liberation books in the basket in front of her. Also, the couch shows rockets with stars which brings the cruise missile issue of the 1980s into the work. Thatcher can also be recognised elsewhere. The girl is sitting on a suitcase with labels showing the migrant experience much more directly than the two black people included in Hogarth’s picture. Himid says her look is saying to the artist ‘stop negotiating and being polite. We have to fight. We’re part of a big political battle’. Hogarth was a sharp critic of the morality of the rising bourgeoisie but was not able to integrate black people into that satire.

The show also re-interprets another iconic painting. Freedom and Change (1984) is painted on a large pink bedsheet, with the two white figures from Picasso’s 1922 painting Two Women Running on the Beach (The Race) re-imagined as two Black women leading a pack of snarling dogs away from the buried heads of two white men.

You are struck by the scale of this installation and it really held the attention of the public when we were there. It works as a dramatic, show-stopping theatrical piece even before you get to the political message.

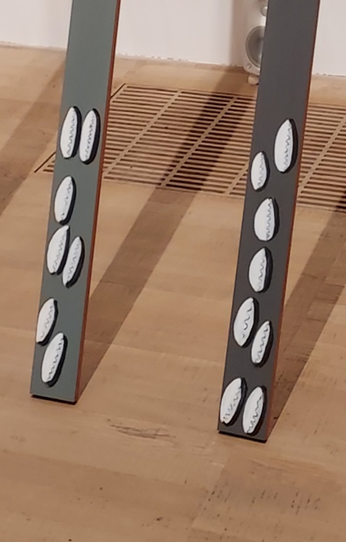

Himid has another large installation called Old Boat/New money placed in the room she has named ‘How do you distinguish Safety from Danger’. The sinuous planks of this boat seem precarious and sweeping. They look like a wave but are the basis of the sort of boat that brought so many million slaves to the Americas from Africa. Cowrie shells painted on them represent currency that was used to finance the trade and also refer us back to the beach which is a site of pleasure and of trauma. The sound of the sea and a creaking ship on the waves accompany the installation.

“What would it be like if this happened to me? How terrifying would this be.. in a moving sinking space, not knowing that it is a wooden sailing ship, on this stuff that I don’t know is the sea? I try to work out how on earth I could actually survive as a human being if I ever go to the other side of the ocean…you’d hand on to these little talismans (the shells)”

Himid, quoted in show booklet.

The paintings are filled with bright acrylic colours. Architectural shapes are very prominent. The situations are ambiguous, both ordinary and extraordinary where unbearable memories of the past bear down and create tension. The Le Rodeur series of pictures is named after a French Slave ship wherein 1819 a disease onboard caused blindness among the slaves. The captain ordered 39 to be thrown overboard. The originality is that the paintings do not show the events directly but instead present us with rather strange, unstable situations. Himid tells us ‘we are seeing overlapping moments of the past and present and that some figures in the scene may be imagined by others’. It is almost surrealist in effect. This picture is the one featured in the booklet and catalogue. There is painful mythology of departure, arrival and exchange with the woman in the centre holding out a piece of textile. For black people whose heritage goes back to slavery the past and present interact in a different way to white people.

Art forum suggests the following interpretation:

One figure has the head of a bird, while another holds out a swath of African patterned fabric; an open window reveals a churning gray sea. The chic setting, evoking the present-day comfort of its inhabitants, is jarred by the ominous sea; a piece of cloth with a hidden past; and the uncanny presence of a bird-headed guest—a messenger perhaps. All allude to a horrific history of struggle and pain.

Finally one of my favourite pictures from the show is this picture of a man (some critics see a woman) about to cut lemons. An ordinary situation but there is that turbulent sea in the window again and the man is looking out of the picture to his right with a look as though he is distracted or worried. Again it is that moment ‘in between’ at the beginning or at the end of a task that intrigues Himid. She says she respects the ‘pastry chefs’ of life who make useful things for us. Then there are the medals and what looks like a party hat. Is he or she in the pay of a colonial army or enterprise? I love the lemon that has slipped off the bottom of the picture and has its own little frame – another surrealist touch. It may look rough and ready but the colours are subtly done with red fading into his shirt and the yellow of the lemons onto his shorts. On the right we have the vertical slash of light and dark green colour which could be a curtain but does it matter, the effect helps close our vision onto the figure. Part of the fun of art is that you do not have to give one closed answer to what you see and enjoy.

Finally, please ignore the mean spirited review (‘promise unfulfilled’) the Guardian critic gave this show and come and see it before it ends on 22 October this year.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Event Video Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War