Close your eyes and imagine all the famous landscape and portrait pictures you may have seen from the Western Art canon. How many Black people did you see? You might have seen a black king in renaissance Epiphany pictures. Black leaders or people killed, imprisoned or defeated in battle are sometimes depicted. It was fashionable to include the liveried black servant at the side or in the background in pictures of aristocratic families.

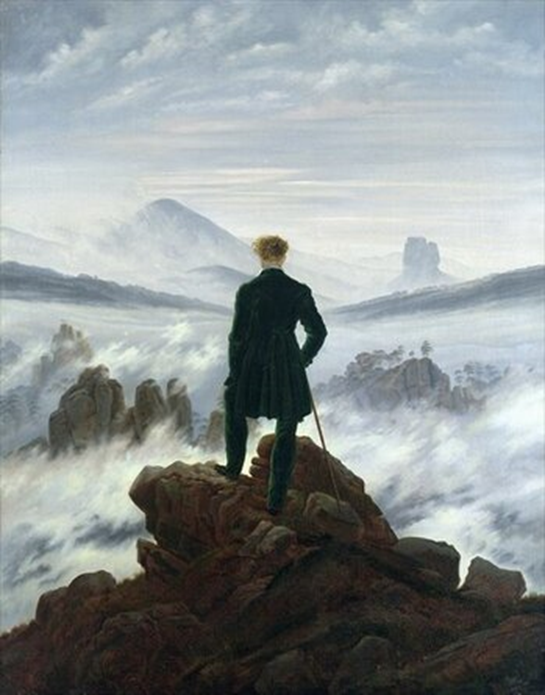

Kehinde Wiley, the black American artist who painted the official pictures of Barack and Michele Obama, has engaged with the Western high art tradition in order to highlight questions of race, gender, migration and marginalisation. His current exhibition confronts the tradition of the sublime in European landscape paintings by visually re-appropriating it with a contemporary black figures. The sublime was very popular in the 19th Century and refers to a ‘greatness beyond all possibility of calculation, measurement or imitation’ (Edmund Burke). Casper Friedrich (1774 -1840) was an exponent of this extreme romanticism. Here is one of his most famous pictures alongside Wiley’s reimagining of it.

Friedrich, Wanderer above the sea of Fog

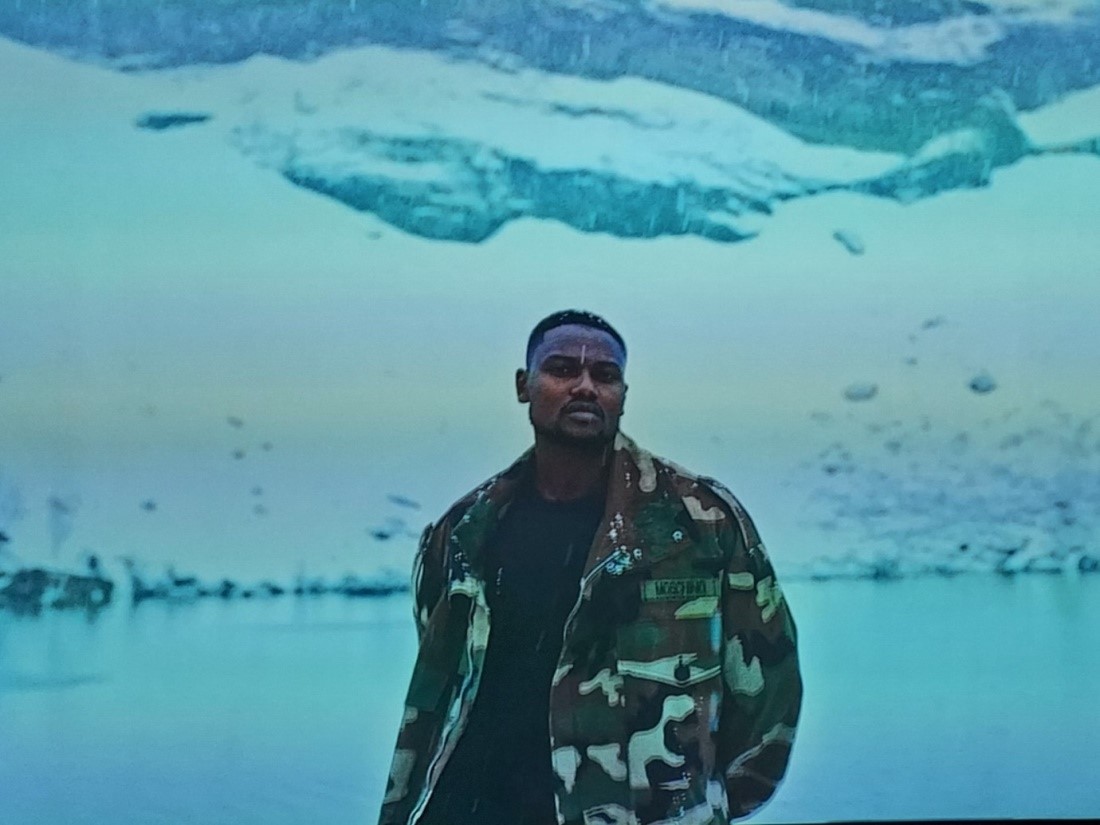

Wiley, Babacar Mane

Wiley gives his figure another staff and dresses him in a rather elegant modern raincoat. He had previously done similar work in relation to the tradition of portrait painting. His take on Holbein’s Ambassadors can be seen here or on the famous Gainsborough picture of the aristocratic landowners, Mr and Mrs Andrews here. (which John Berger’s masterwork, Ways of Seeing, also dissected brilliantly)

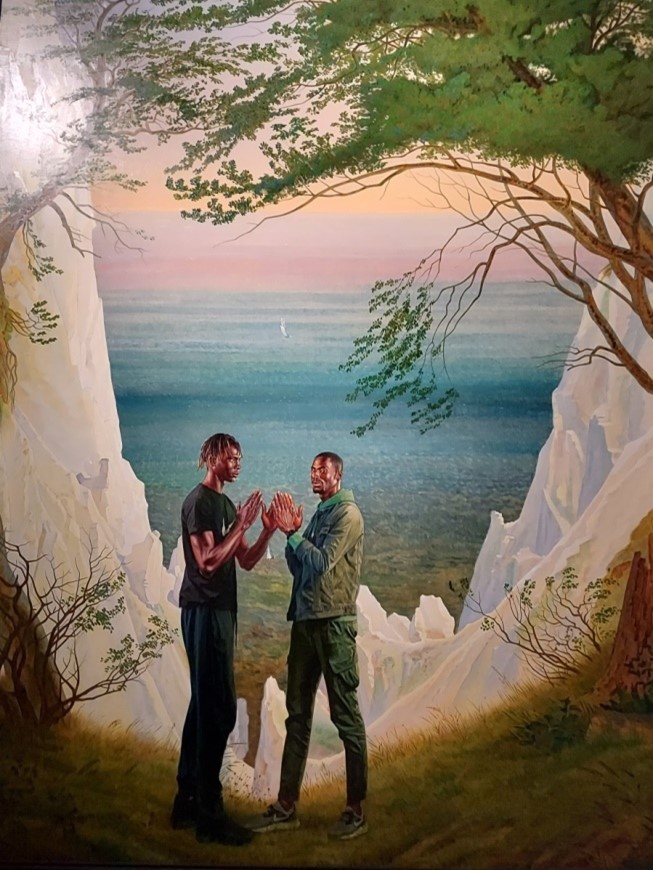

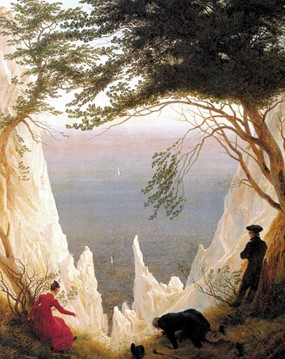

In this exhibition he deliberately focuses on the contrast between whiteness/light in Western art and blackness. In an interview with Zoe Whitley in the exhibition catalogue (p25ff) Wiley discusses the longstanding correlation in Western culture between purity, divinity and whiteness, with the representation of light as a ‘stand in for whiteness itself’. This can be seen clearly in Friedrich’s work below (Chalk cliffs on Rugen). Wiley puts his black protagonists in a sunlit chalk precipice, he visualises how for him ‘whiteness becomes a metaphor for a cage’. Indeed the way he places the figures emphasises their precariousness in front of the abyss. They are playing a hand clapping game popular in black culture among children – we see this game repeated with the people featured in the six channel digital film, Prelude which completes the exhibition.

Wiley, Ibrahima Ndlaye and El Hadji Malick Gueye

Friedrich, Chalk Cliffs on Regen

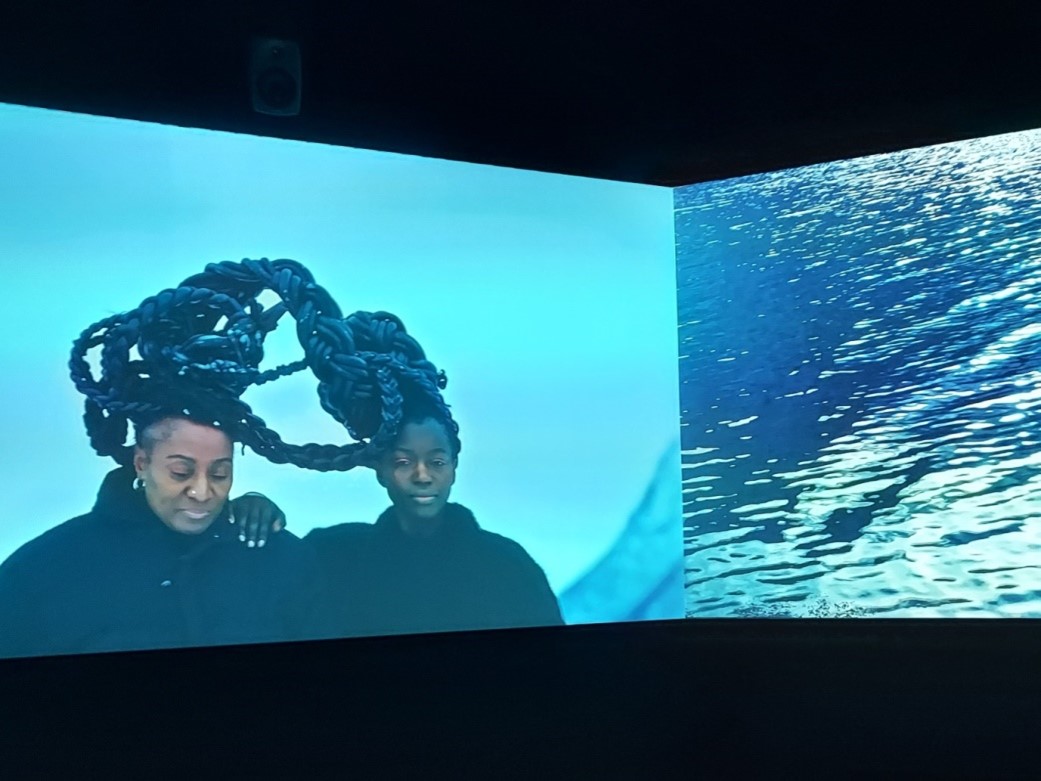

Wiley’s film Prelude

You can immerse yourself in a near 360 degree experience with six screens split between each side of the oval room. It lasts over twenty minutes and you can enjoy the original music score (Niles Luther) and stunning images without necessarily tuning into his message or the poetry that is spoken and subtitled onto the film. We got the sense that people really got into the film and its inspiring music. Despite its length and lack of conventional narrative people stayed for the whole thing. It stirred you and made you reflect.

Wiley recruited Black Londoners he met in Soho to take to the shoot in Norway with its fjords and glacial landscapes. The artist wanted his figures to really experience the cold and harshness of the landscape – ‘the temperature of the north becomes a character in the room’. As with the paintings in this show he wanted to repeat the metaphor of black figures (originally from a warmer south) being surrounded and occasionally subsumed, by whiteness. In an earlier film, Narrenschiff (2017) based in Haiti highlighting themes of migration and borders, he stated that ‘the ocean becomes a stand-in for the way we have traditionally viewed the global South as being the opposite of the rational North‘.

The title of the film references William Wordsworth’s autobiographical poem which was all about the poet’s spiritual development through his communion with the natural world. This is the other theme Wiley wants us to understand. He is not just concerned about racism or colonialism but also fervently believes we need to become absorbed in nature and through that we can be inspired to have a deeper connection with humanity. The movements of the figures in the landscape again echo themes form Western Art, such as the Romantic solitary – and always white and male – wanderer. Words and poetry from Wordsworth, Emerson and Thoreau are recited during the film. Whatever we may think about the idea of the divine or immortality in nature, socialists today have to profoundly change their mindset about humanity’s exploitation of the natural world and accept our existential connection to it.

‘So often mountains have been positioned as something to be conquered, something to climb and to hold up as a trophy to anyone’s individual ability to be dominant over nature’

Wiley, (p94, catalogue)

Images from the film, Prelude

Images from the film, Prelude

Already it appears this show is pulling in the crowds. It is free to enter and can be done easily in an hour. It seemed to me to be drawing in a younger and more ethnically diverse crowd than you usually see in the National Gallery exhibitions. This show can easily be slotted into an hour before or after a demonstration!

Art Book Review Books Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Event Video Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review France Gaza Global Police State History Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party London Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants NATO Palestine pandemic Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War