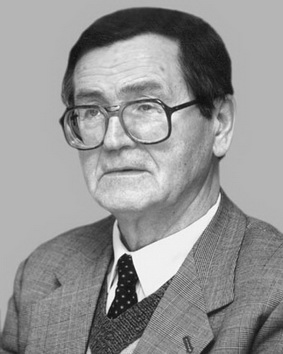

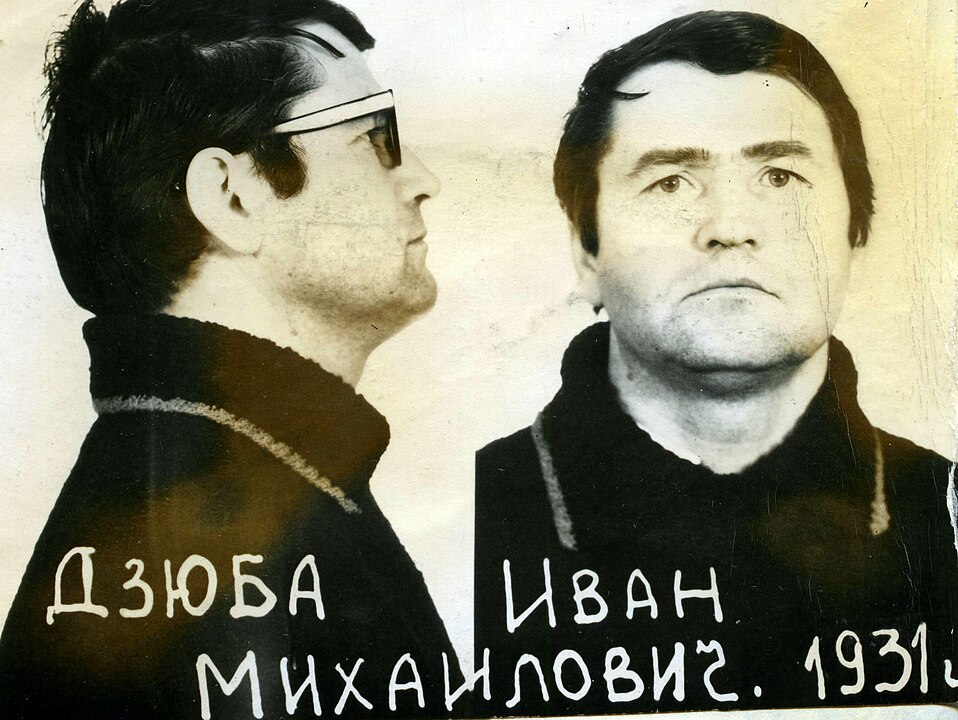

Ivan Dzyuba was born into a peasant family on 26 July 1931 in a village in the Donbas coal mining region of the Ukrainian SSR. In 1949 he left his secondary school and entered the faculty of philology at the Pedagogical Institute in Donetsk (then Stalino). After graduating, he did research work in the T. Shevchenko Institute of Literature of the Ukrainian SSR Academy of Sciences. Subsequently he worked as an editor for the State Literary Publishing House of Ukraine, was in charge of the department of literary criticism of the journal Vitchyzna (the leading organ of the Writers’ Union of Ukraine), and was a literary adviser for the publishing house Molod (Youth).

Dzyuba’s work in literary criticism has been appearing in print since 1950; in this genre he has displayed remarkable insight, opening up for his readers entirely new approaches to literature. He carries his readers with him by a striking lucidity of exposition, and is no respecter of accepted opinion. His work has done much to encourage new trends in Soviet Ukrainian literature, and he is· held in high esteem among the younger generation of writers and readers. His articles have been published not only in various periodicals in Ukraine but also in a number of Russian journals; he has also contributed to journals in Georgia, Czechoslovakia and Poland. The first publication of his work in English was in the Moscow journal Soviet Literature (No. 10, 1960).

Dzyuba’s boldness and originality has not remained unchallenged by the conservative literati who have reproved him from time to time, as in June 1962 for instance, when the Presidium of the Writers’ Union of Ukraine accused him of ‘giving a distorted view of the real state of contemporary Ukrainian literature’ and of uttering ‘politically erroneous statements’,1 and threatened him with expulsion from the Union.2

In late August and early September 1965, a week or two before the arrests of A. Sinyavsky and Yu. Daniel, a number of political arrests among young intellectuals took place in Ukraine. On 4 September, Dzyuba, together with V. Chornovil and V. Stus, appealed to an audience in the ‘Ukraina’ cinema in Kyiv to protest against these arrests. No official statements were issued regarding them, nor was any answer given to enquiries about them addressed to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine by eminent people – deputies of the Supreme Soviets of the USSR and the Ukrainian SSR, Lenin Prize laureates and holders of the Order of Lenin. Instead of clear official statements in the press, rumours about the arrests of ‘nationalists’ gained ground. Motivated by his conviction that those arrested were not ‘nationalists’ but people genuinely concerned for the condition of Ukrainian culture, and himself witnessing numerous instances ‘of an indefatigable, pitiless, and absurd persecution of the national cultural life’ of Ukraine, Dzyuba wrote the present book in the last months of 1965 in order to show that ‘the anxiety felt by an ever-widening circle of Ukrainian youth’ was the result of the abandonment of the Leninist nationalities policy by Stalin and Khrushchev. Dzyuba asserts that a policy of persecution is no answer; in his opinion, the restoration of the Leninist policy is indispensable for the good of Communism and its future progress.

His book, consisting of a thorough examination of the historical background of the nationalities problem, of the Leninist policy on it, of its subsequent abandonment, and the means whereby it should be restored, was presented to the leaders of the Communist Party and the Government of the Ukrainian SSR and also, within a month, in a Russian version, to the Central Committee of the CPSU. Shortly after receiving it the Central Committee of the CPU distributed it in a limited number of copies for internal circulation among the regional (oblast) Party secretaries (there are twenty-five regions in Ukraine) requesting their comments (these have so far not been revealed). The book subsequently began to circulate in Ukraine and beyond its borders.

Following the protest, he staged in the Ukraina cinema, in September 1965 Dzyuba was dismissed from his post with the Molod publishing house, and was given the post of language editor with the Ukrainian Biochemical Journal as from the January 1966 issue.’ Six months later, the Secretary of the Kyiv Communist Party Committee, writing in the Party organ Komunist Ukrainy, attacked Dzyuba (together with two other writers) for ‘ideologically harmful statements’ and other equally vaguely formulated offences,3 and in September the satirical journal Perets’ published a rather scurrilous lampoon of him,4 soon answered by three journalists, among them Dzyuba’s fellow-protester Chornovil, who courageously came to his defence in a letter to the Perets’ editorial board (which has remained unpublished). Then in November, Dr S. Kryzhanivs’ky, a poet of the older generation, a literary critic and scholar and Party and Writers’ Union member, vindicated Dzyuba from the rostrum of the Fifth Congress of Writers of Ukraine, naming him, together with another critic, as the only ones who dared to speak the truth (this was published).5 In January 1968, Dzyuba returned to his first post as an editor with the State Literary Publishing House (now renamed Dnipro), and was also readmitted into print in the USSR for the first time in two and a half years. He was also busy with other books (his first, entitled ‘An Ordinary Man’ or a Philistine?6 appeared in 1959); they included a history of thought in Ukraine, a book on T. Shevchenko (He Who Chased out the Pharisees) and one on V. Stefanyk.

In the meantime, the arrests of 1965 (which impelled Dzyuba to write the present work) were followed by a series of trials. The first two, in January-February 1966, were conducted in a way similar to the well-known one of Sinyavsky and Daniel, which also occurred that February, and the charges brought, of anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation, were also similar. The remaining nine trials, although the charges brought were again similar, were held in February-April and in September in camera (in breach, it must be noted, of the Soviet law on this point). Sentences of from eight months to six years were passed, and five of the accused are still, at the time of preparation of this edition (June 1970), in strict regime camps or prison.

Among the considerable number of inquiries about the fate of those arrested and of protests against their harsh sentences, that from Chornovil stands out by the fullness of its documentation and its convincing argumentation. In his letter, like Dzyuba’s book, addressed to the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPU, P. Yu. Shelest, as well as to the highest legal and security authorities of the Ukrainian SSR, he demonstrates, by referring to specific articles of the Soviet Constitution and Soviet legal codes, that the majority of the trials were illegal because they were not public, and, moreover, that the investigation and trial procedures contained a number of grave breaches of certain fundamental and specific legal safeguards, thus invalidating both the trials and the sentences passed. Chornovil’s serious specific charges against the judiciary and the security services remained unanswered for nearly fourteen months; in the meantime, by April 1967 he had compiled another document – a ‘White Book’ on the accused,7 to which, in early August, the security authorities did answer: Chornovil was arrested, and sentenced fifteen weeks later to three years’ labour camp, halved under a general amnesty; he is now free.8

Louis Aragon declared that the Moscow sentences create ‘A precedent, more harmful to the interest of socialism than the works of Sinyavsky and Daniel could be. It is to be feared, in fact, that one could think that this kind of procedure is inherent to the nature of communism’,9 and John Gollan’s conclusion was that ‘The court have found the accused Guilty, but the full evidence for the prosecution and defence which led the court to this conclusion has not been made public. Justice should not only be done but should be seen to be done. Unfortunately, this cannot be said in the case of this trial.’10 It must be remembered that there was at least some (though admittedly one-sided) discussion of the Sinyavsky and Daniel case in the Soviet press, that the trial was (though incompletely) reported in Soviet papers, and that some members of the public were admitted to the trial; but not a single word appeared in the Soviet press about the arrests and trials in Ukraine, and all the translate from late February 1966 were held in camera. Compared with them, even the 1968 Moscow trial was much more public, although the Morning Star wrote this about it in its leader of 13 January 1968:

Outsiders are in a difficulty when forming an opinion of the trial and sentences on Yuri Galanskov and others in Moscow.

Neither friends nor enemies of the Soviet Union in Britain know what went on in the courtroom, what evidence was produced, or what the witnesses said.

Louis Aragon’s fears may well now be reinforced, and one cannot but say with John Gollan that justice most definitely has not been seen to be done; – more than that, allegations of a grave miscarriage of justice can no longer be brushed aside, under the circumstances as they are now known.

In fact, a recent report of a Canadian Communist Party delegation to Ukraine also speaks of ‘cases of violation of Socialist democracy and denial of civil rights’ there, and continues: ‘When inquiries were made about the sentencing of Ukrainian writers and others, we were told … that they were convicted as enemies of the state. But the specific charges against them were not revealed. Although we do not claim to know what considerations of state security led to the trials of these writers being conducted in secret, we must make the point that such in camera trials never serve to dispel doubts and questioning.’11

Dzyuba’s work shows the historical and contemporary background, the social, cultural, and political processes in the light of which these events must be viewed. But he himself does not view these processes from the outside; he is deeply involved in them, feels responsible for what is happening, and ardently advocates a return to Leninist justice. A man of letters, Dzyuba is always mindful of these words of Jean-Paul Sartre which have now gained fresh poignancy:

The writer is in a situation in his time: every word has repercussions. Every silence too. I hold Flaubert and Goncourt responsible for the repression that followed the Commune because they did not write a line to prevent it. It was not their business, one may say. But was the trial of Galas, Voltaire’s business? The condemnation of Dreyfus, was it Zola’s business? Each of these authors, in a particular circumstance of his life, measured his responsibility as a writer.12

Footnotes

- This he was supposed to have done in a lecture delivered in L’viv which has remained unpublished, and therefore it is difficult to ascertain the reality of these allegations. ↩︎

- ‘U prezydiyi SPU’, Literaturna Ukraina, 29 June 1962. ↩︎

- V. Boychenko, ‘Partiyni organizatsiyi ta ideologichne zahartuvannya tvorchoyi inteligentsiyi’, Komunist Ukrainy, No. 6, June 1966, p. 17. ↩︎

- Perets’, No. 17, September 1966, p. 5. ↩︎

- Literatuma Ukraina, 20 November 1966, p. 5. It is said that at the mention of Dzyuba’s name the audience’s thunderous applause nearly raised the roof. ↩︎

- I. Dzyuba, ‘Zvychayna lyudyna’ chy mishchanyn? Litnatumo-krytychni statti, Kyiv, 1959, 277 pp. ↩︎

- Both documents in The Chornvil Papers, McGraw-Hill, 1968. ↩︎

- Full documentation of his case, as well as more recent writings by some of these, and certain earlier, prisoners, appeals on their behalf by Dzyuba and others, and other relevant documents, with a survey of events in Ukraine from 1965-8, published Macmillan in M. Browne (ed.), Ferment in Ukraine. Conditions in the camps are well documented in Rights and Wrongs, Penguin, 1969, and A. Marchenko, My Testimony, Pall Mall, 1969. ↩︎

- L. Aragon, ‘Apropos d’un procés’, L’Humanité, 16 February 1966, p. 3. [Translation by the editors] ↩︎

- ‘British Communist Protest at Soviet Sentences’, The Times, 15 February 1966. ↩︎

- Viewpoint (Central Committee Bulletin, CP of Canada), Toronto, January 1968, p. 11. ↩︎

- J.-P. Sartre, ‘Presentation’, Les Temps Modernes, No. 1, October 1945, p. 5. [Translation by the editors]. ↩︎

Art (55) Book Review (127) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (46) EcoSocialism (60) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (64) Film (48) Film Review (69) France (72) Gaza (63) Imperialism (101) Israel (130) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (57) Labour Party (116) Long Read (42) Marxism (49) Marxist Theory (47) Palestine (186) pandemic (78) Protest (154) Russia (345) Solidarity (153) Statement (50) Trade Unionism (144) Ukraine (351) United States of America (140) War (371)