A view of Kitson from the Troops Out Movement

When Barack Obama became President of the USA in 2008, there was alarm at the heart of the British state, when they realised that around sixty years before, their security forces in Kenya had tortured the new President’s grandfather, Hussein Onyango Obama. This occurred during a revolt against British colonial rule. Hussein’s wife, Sarah, described his ordeal: “They would sometimes squeeze his testicles with parallel rods. They also pierced his nails and buttocks with a sharp pin, with his hands and legs tied together with his head facing down.”

General Sir Frank Kitson, who has died last week at the age of 97, served, as a young officer, in Kenya, where he’d gained prominence for his work in setting up ‘counter-gangs’. He’d joined the British Army soon after World War Two and was promoted and decorated for helping to sharpen the army’s counter-insurgency techniques in Kenya, Malaya and Cyprus.

Post-World War Two, during ‘Cold War’ anti-communist hysteria, there were over sixty attempts to engineer regime change around the world, covertly set-up by the intelligence agencies of the US and Britain. Reactionaries seized power through military-coups in places like: Iran 1953, Democratic Republic of Congo 1961, Brazil 1964, Ghana 1966, Indonesia 1967, Greece 1967, Bolivia 1971 and Chile 1973.

British troops had also been continually involved in a series of campaigns including: Palestine 1945-48, India/Pakistan 1945-47, Malaya 1948-60, Kenya 1952-60, Cyprus 1954-59 and Aden 1955-67. Many of these were colonial conflicts, but cocooned in a media web of ‘Our boys doing a jolly good job in trying circumstances’, ‘peace keepers’ amid ‘bandits’, ‘extremists’ and ‘terrorists’, the folks back home rarely asked any questions.

The truth was very different, as these colonial ‘small-wars’ were about power, hegemony, natural resources, cheap labour and profits. Intimidation, internment, torture and killings were systematically used by our troops to ‘protect British interests’.

During the 1960s, as worker and student struggles erupted across the world, in Derry and Belfast civil rights protesters were being batoned off their own streets by the Royal Ulster Constabulary. In August 1969, after an annual Orange march in Derry, the RUC tried to force their way into the Nationalist Bogside area, as they had often done before. This time, however, they were met by determined resistance from the local people and, after two days of street fighting, British troops were ordered to go in and replace them.

A brief ‘honeymoon period’ occurred between the soldiers and the Nationalists, who had regarded the entry of the troops as a victory over the Unionist Government at Stormont and the RUC. The ruling class, however, knew they were struggling to maintain their control and in 1970 Frank Kitson – now a Brigadier – was posted to Belfast to command the 39th Infantry Brigade.

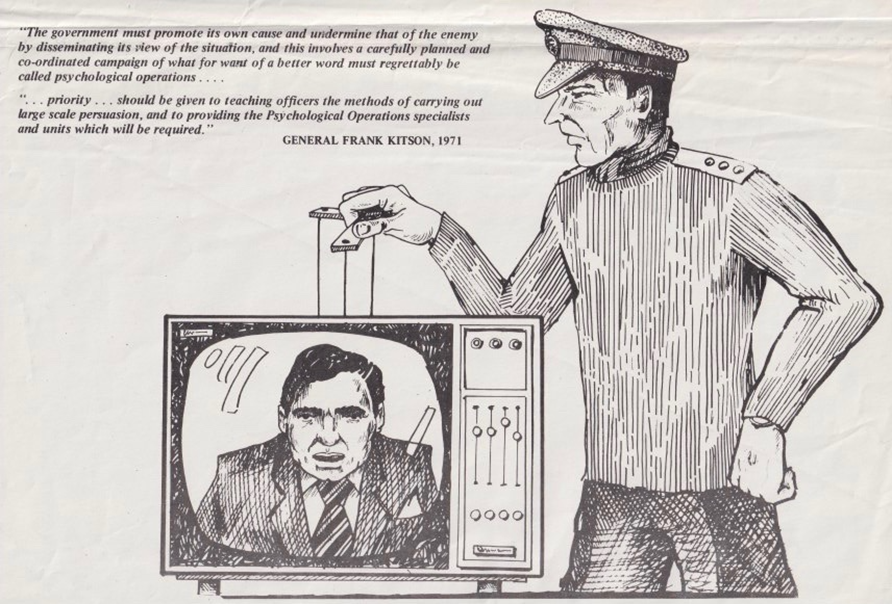

Kitson’s appointment reflected the changing military emphasis to counter-revolutionary operations. In essence, it signalled the start of an army offensive against the Nationalist community, using the Ministry of Defence’s latest Land Operations manual as their blueprint. It contained sections on “The Threat” and “The Principles for the Conduct of Counter-Revolutionary Operations” and details of how “psychological operations”, “military actions” and “political initiatives” must be co-ordinated.

Given carte blanche by Westminster and egged on by the Unionists in Stormont, the army embarked on a series of aggressive operations. These included: The Falls Curfew 1970, Internment 1971 and Bloody Sunday 1972. These did not cow the Nationalists, however, but instead triggered a violent resistance.

There had also been an on-going debate in Nationalist areas questioning whether they should they continue their civil-rights struggle by peaceful political means? Or, because of the violence being used against them: Should they resort to using violence themselves? Bloody Sunday, when 14 peaceful demonstrators were shot dead by soldiers of 1 Para in Derry, dramatically resolved this discussion in favour of the latter. The day after Bloody Sunday there were long queues of locals outside the Sinn Féin office in Derry – and nearly all of them wanted to join the IRA.

British politicians and the Army top brass did not change course. Instead, they increased the repression and in July 1972 launched Operation Motorman – then the largest British military operation since Suez in 1956 – against the resistance in Nationalists areas. A series of army forts were subsequently built in the heart of these now occupied territories.

In October 1972, the IRA killed the driver of a Four-Square laundry van at the Twinbrook estate in West Belfast and also attacked a massage parlour on the Antrim Road. Both had been set-up by the Military Reaction Force (MRF), which was partly a clandestine surveillance unit, partly a ‘counter-gang’, and partly an undercover assassination-squad that operated, under Kitson, from Palace Barracks.

The Four-Square laundry van was being used for surveillance work in hard-line areas, with forensic tests carried out on the clothes taken for cleaning. The Gemini Health Studios, which advertised ‘attractive masseuses’, was used to procure informants. A report stated that “cameras were used by hidden agents to record people in compromising positions, and force them to spy on the IRA.” The Labour MP, Joan Maynard, demanded to know in Parliament whether “the British Army was setting up brothels in Belfast for espionage purposes?”

A year later in ‘Operation Lipstick’, female British Army personnel with Irish backgrounds, were carrying out door-to-door sales of cosmetics and running ‘underwear selling parties’ in West Belfast. And the files of the RUC Drug Squad were used to arrest youngsters, who were offered drugs, cash and immunity from further arrest in return for information. The use of ‘touts’, ‘informers’ and ‘supergrasses’ became a crucial part of counter-revolutionary strategy in the war.

Although only in Belfast for under two years, Kitson was at the heart of the violence and the ‘dirty war’ that evolved over the following decades:

- He introduced ‘covert-operations’ and set-up the MRF, which ‘colluded’ with Loyalist paramilitaries (friendly forces against a common enemy).

- He took a dominant role in ‘psyops’, which included seeking to control and manipulate the media reporting of the conflict.

- He sought to extend the use of special units, like the SAS, and to progress their integration into the military command structure.

- He believed in the ‘pacification’ of disaffected populations and punishing them for harbouring revolt.

In Belfast, Kitson kept 1 Para – nicknamed ‘Kitson’s private army’ – in reserve. And if one of the infantry regiments was experiencing difficulties, he would withdraw them temporarily and send in 1 Para – to dish out retribution. This resulted in the massacres at Ballymurphy in August 1971 and on Bloody Sunday in Derry, five months later.

Kitson, who was awarded a CBE for his ‘service’ in Belfast, was a public-school educated upper-class warrior for the rich and powerful. A modified version of his methods was used in the 1984/5 miners’ strike against the National Union of Mineworkers, whom Thatcher called: “the enemy within”.The people who were subject to Kitson’s full treatment in Kenya, Malaya, Cyprus and Ireland will not mourn his passing. And neither should we.

Source >> Labour Hub

Art (54) Book Review (127) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (46) EcoSocialism (60) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (62) Film (48) Film Review (68) France (72) Gaza (62) Imperialism (101) Israel (130) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (56) Labour Party (113) Long Read (42) Marxism (49) Marxist Theory (47) Palestine (183) pandemic (78) Protest (153) Russia (343) Solidarity (151) Statement (50) Trade Unionism (144) Ukraine (351) United States of America (140) War (371)