Source > Michael Roberts blog

China’s Congress of the Communist Party takes place this week. This is an important event not only for China but globally. The Western media have concentrated on the fact that current party leader Xi Jinping will be confirmed for an unprecedented third term as party leader and thus also continue as President of China when the National Congress meets next March.

Naturally, Western pundits are strongly opposed to Xi having a third term. The FT’s Keynesian guru, Martin Wolf reckoned Xi’s continuation in power would be ‘dangerous’ for China and the world. “It is dangerous for both. It would be dangerous even if he had proven himself a ruler of matchless competence. But he has not done so. As it is, the risks are those of ossification at home and increasing friction abroad… Ten years is always enough.. It is simply realistic to expect the next 10 years of Xi to be worse than the last.” And apparently, that has been bad enough.

The antagonism to Xi and the current leadership is less to do with the lack of democracy and one-party rule in China – the Western pundits and international agencies seldom mentioned that in their past analyses of China before Xi took over. The strong antagonism now is really to do with two things: 1) under Xi, China’s economic policy has emphasised state control and a reduction of the sway of the capitalist sector; and 2) under Xi, China is resisting to being contained and squeezed by US imperialism in its escalating attempt to stop China’s progress as a major rival in trade, technology and global influence.

When it comes to the current state of China’s economy and its future prospects, Western analysts (and especially those based nearby in Hong Kong, Taiwan etc) veer from reckoning that the Chinese economy is about to implode under the weight of record-high debt and a property bust to long-term stagnation due to demographics, the lack of consumer demand and slowing productivity growth, induced by Xi’s bias towards the state over the market.

For decades, Western analysts have been predicting China’s demise and collapse under the weight of rising debt and state control. That has not materialised. Now the main emphasis is on arguing that China can no longer expand its national output at any reasonable pace and won’t be able to get out of what is called the ‘middle-income trap’ and so meet the needs of an urbanized population – unless it breaks with its state-led economy and allows the capitalist sector to flourish to meet the consumption demands of the burgeoning middle-class.

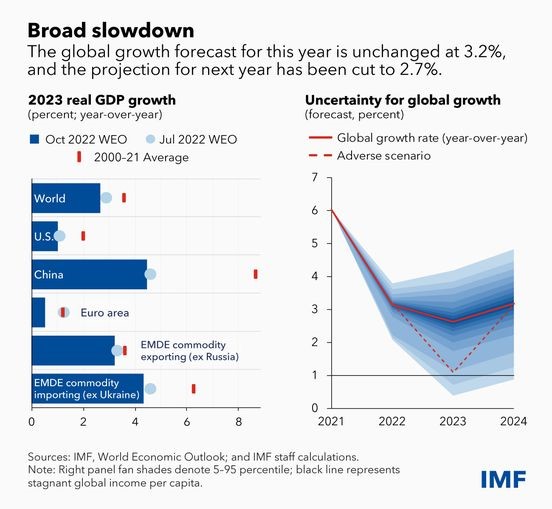

But is this view of China’s economic future any more accurate than the one adopted for the last two decades that China was about to implode? First, what is the current state of the economy? For the first time since the 1990s, China’s real GDP growth this year and next is likely to be lower than the average growth in the East Asian region. This year, economic growth will probably be under 3% and next year rising to about 4.5%. That’s well below the long-term target of about 5% a year.

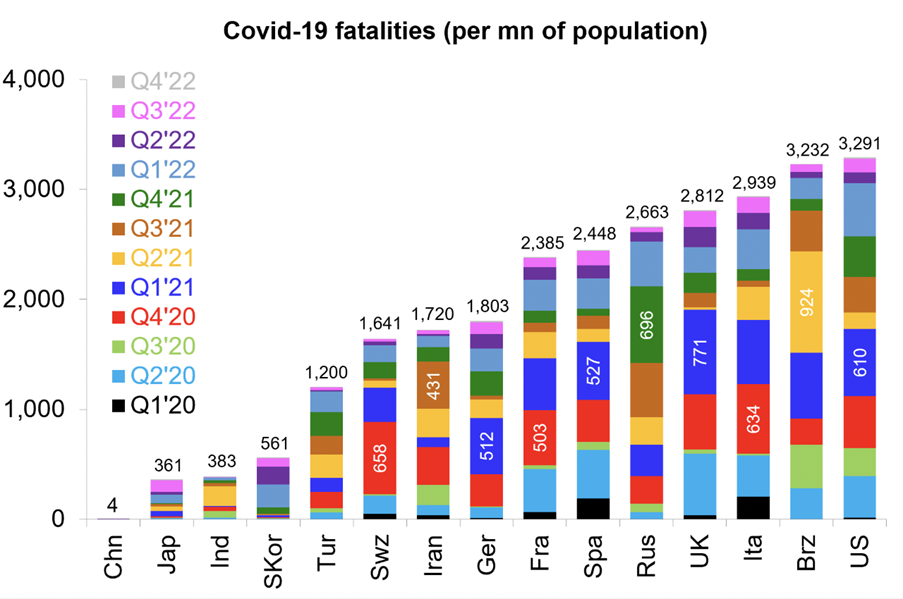

Why is this? There are two reasons. The first is the impact of COVID and China’s zero COVID policy. The West never had such a policy and eventually just relied on vaccinations to overcome the worst of the COVID impact on lives and health. But the virus in various forms continues to spread across economies, delivering yet more deaths and above all lingering ‘long COVID’ illnesses that have stopped millions from working. China rejected this ‘open up the economy’ approach. Instead, it imposed strict and drastic lockdowns at the first sign of infections picking up and is still doing so. The government was not prepared to repeat the disaster of the first eruption in Wuhan. As a result, China has had the lowest death rate from COVID in the world.

The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention warned that if the country followed the opening-up strategies taken by countries such as the UK and the US, it would cause hundreds of thousands of cases a day, of which more than 10,000 would present severe symptoms if there was a sizeable community outbreak. “We are not ready to embrace ‘open-up’ strategies resting solely on the hypothesis of herd immunity induced by vaccination advocated by certain western countries,” the Center wrote.

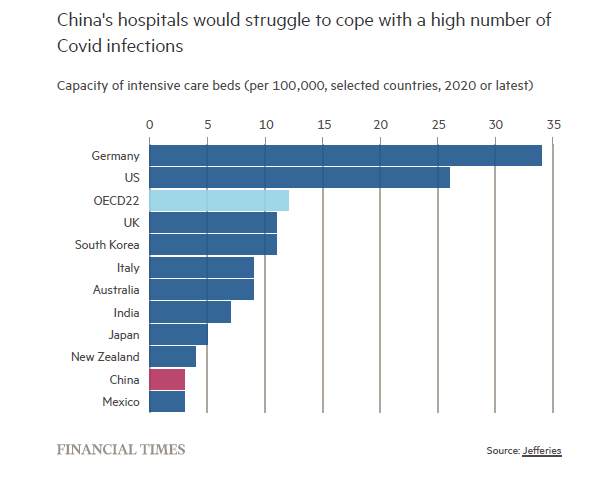

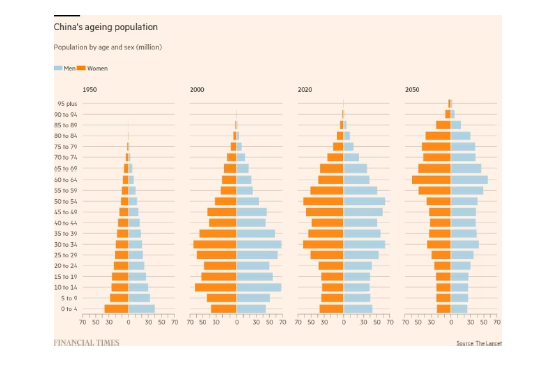

A key reason that China adopted lockdowns, as well as vaccinations to curb COVID, was its relatively weak public health service and the lack of the latest and most effective mRNA vaccines. China has a patchy network of poorly-resourced hospitals and a huge elderly population at a higher risk of severe illness, as well as comparatively low efficacy of its domestically-produced vaccines. While there are more hospital beds per capita in China than in the US and the UK, the number of intensive care beds available — crucial to keep Covid-19-infected patients alive — is a quarter of the OECD average. Resources are especially thin outside of the big cities; rural areas have half the doctors and beds on a per capita basis of urban areas.

China rolled out the first wave of vaccinations at breakneck speed, at its peak jabbing more than 22mn people a day. Domestically, 3bn vaccine doses have been administered to the country’s 1.4bn people. China has sent around 1.6bn vaccine doses to developing countries, making it the world’s single largest exporter of jabs. Chinese health officials and experts believe they have prevented at least 200mn infections and 3mn deaths.

However, there are signs that the domestic jabs, which use traditional inactivated vaccines — where the pathogen is killed or modified so it cannot replicate — produce weaker immune responses to the Covid-19 virus than the newer messenger RNA used in Moderna and BioNTech/Pfizer jabs and the viral-vector technology in Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca. Over the past 12 months, the spread of the highly infectious Delta and Omicron variants has put the spotlight on fading efficacy of these vaccines. The lockdowns have continued on and off throughout this year and this has made economic recovery more intermittent and weaker as a result.

But China opted to save lives over economic expansion. Of course, Western analysts claim that China’s lockdown ‘zero COVID’ policy is more to do with controlling the population by an autocratic regime – yet most opinion surveys in the past have shown broad support for the policy among the population, although it is true that ‘lockdown fatigue’ is beginning to have an impact, mainly because there is no democratic decision-making on health policy, which is just imposed from above.

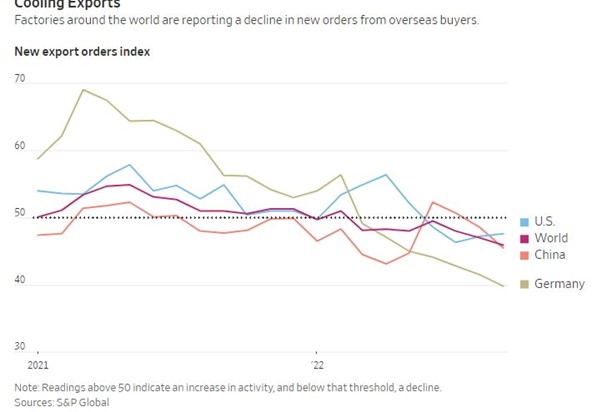

The other reason that China’s economic growth has slipped this year is the general slowdown towards a slump in the rest of the world. The major capitalist economies are stuck in supply-chain congestion, weak investment expansion and now rising interest rates and inflation that threaten outright global recession.

World trade growth has fallen away. The World Trade Organisation reckons that total exports and imports of goods are likely to grow by just 1% in 2023. The most recent World Bank projections put China’s GDP growth for the year at 2.8%, down from its initial forecast of 5% and well below the rest of Asia.

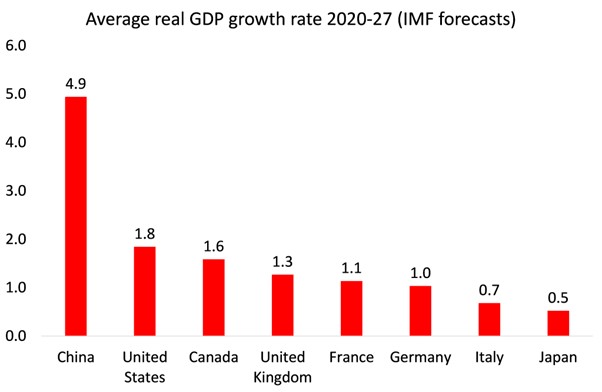

But China is not heading into a slump like the G7 economies. Indeed, both the World Bank and the IMF expect China’s real GDP to rise by over 4% next year, while most G7 economies will be contracting or have near zero growth.

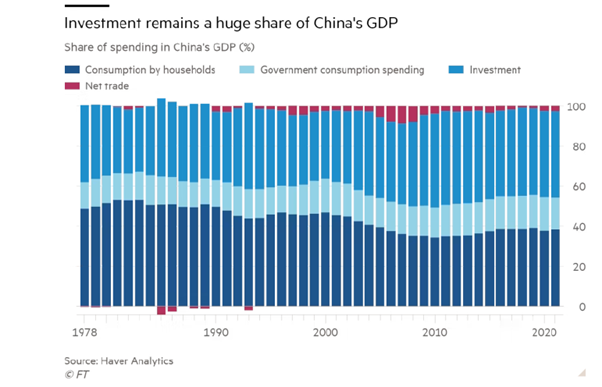

Looking longer term, Western analysts reckon China is heading for much slower growth and this will threaten Xi’s future. Up to now, China’s unprecedented economic growth record has been based on high investment rates and exports of manufactured goods to the rest of the world.

But the COVID slump and the dissipating global economic recovery have hit export growth hard. Exports fell in dollar terms by 1% in the year of the COVID slump and then rose sharply in the 2021 global recovery year by 21%. But in the first eight months of this year (2022) exports are down to 7.1% yoy. As a result, industrial production has risen only 3.6% and retail sales up only 0.5%. Fixed asset investment has remained stronger at near 6% yoy, based on increased infrastructure investment (roads, rail, bridges and public services).

From hereon, Western analysts claim that China will enter a period of low growth and will not escape the ‘middle-income trap’ that so many so-called emerging economies are locked into. China will not catch up even with the GDP level of the US as previously expected.

This claim is based on two assumptions. First, China’s ageing population and the declining working-age sector will reduce growth rates and second that the high-saving, high-investment model of Chinese growth no longer works.

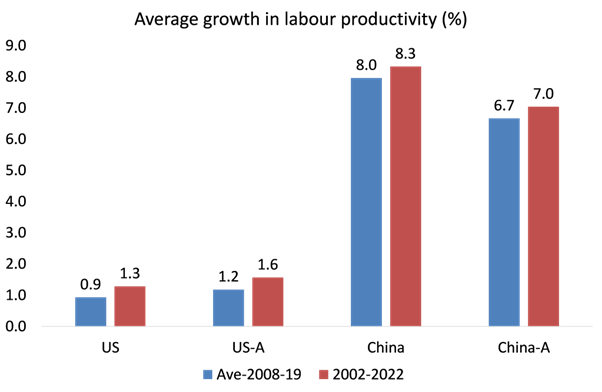

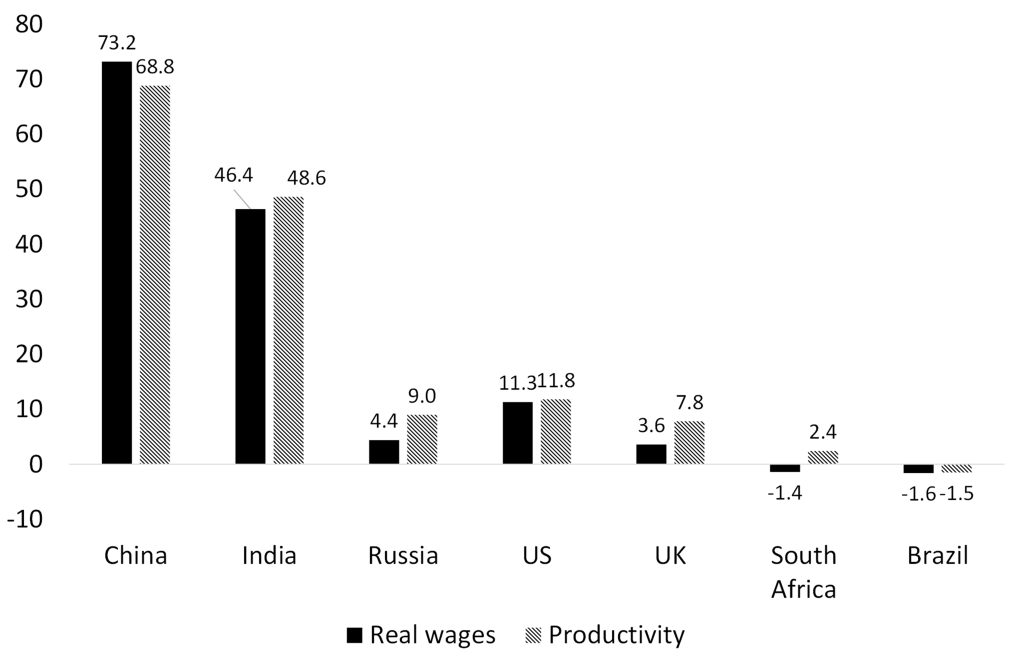

China won’t be able to grow as fast as before as the working population is declining and there will be an insufficient rise in the productivity of labour to compensate. I have discussed at length in previous posts these claims by Western experts that China’s falling working-age population and its slowing productivity growth rate mean that it will begin to fail. The arguments are weak and faulty. Indeed, even on the adjusted (A) Western measures of labour productivity growth during the COVID period, China has done way better than the ‘dynamic’ USA.

Longer term, the IMF forecasts that China will grow at a subdued rate of 5% a year. But that rate would still be more than twice as fast as the US, and more than four times as fast as the rest of the G7 – and that’s assuming no slump in the G7 economies in the next five years.

The other argument of the Western analysts is that China cannot grow at any reasonable pace from hereon unless it switches from a high-savings, high-investment, export-oriented economy to a traditional consumer-led capitalist economy existing in most of the major capitalist economies, particularly the US and the UK. The usual basis for this view is that personal consumption rates are too low in China and this will hold back demand-led growth.

For example, take this view by Chen Zhiwu, a professor in Chinese finance and economy at the University of Hong Kong. Chen argues that, under Xi, major reforms towards the private sector, consumer-led economies have been sidelined. “The 60 reforms would have largely expanded the role of consumption and private initiatives,” he says. “However, the market-oriented reform agenda has been largely sidelined . . . resulting in a larger role for the state and a shrunken role for the private sector.” According to Chen, this will mean China’s economy will stagnate from hereon.

Another prominent and widely-followed Western analyst, Michael Pettis, who is based in Shanghai, makes a similar argument, namely that what will push China into Japanese-style stagnation is the failure to expand personal consumption and continue to expand investment through rising debt. It is no accident, in my view that both these analysts come from the finance sector.

And yet how can anybody claim that the mature ‘consumer-led’ economies of the G7 have been successful in achieving steady and fast economic growth, or that real wages and consumption growth have been stronger there? Indeed, in the G7 capitalist economies consumption has failed to drive economic growth and wages have stagnated in real terms over the last ten years, while real wages in China have shot up.

This is the real point. Consumption is rising much faster in China than in the G7 because investment is higher. One follows the other; it is not a zero-sum game. Pettis’ view is a crude Keynesian analysis that ignores even Keynes’ view himself that it is investment that grows an economy with consumption following, not vice versa.

And not all consumption has to be ‘personal’; more important is ‘social consumption’, that is, public services like health, education, transport, communication and housing; not just motor cars and gadgets. Increased consumption of basic social services is not accounted for in the personal consumption ratios. China has a long way to go in social consumption too, but it is way ahead of its emerging market peers in many social areas and not so far behind leading G7 economies, which started more than 100 years before. I defer to Citibank’s economists in their recent in-depth study of the Chinese economy “In other words, it is quite possible for the Chinese economy to deliver greater opportunities for consumption without consumption being a specific target for policy.” “household disposable income has been growing faster than GDP in real terms in the past few years (except 2016), a trend likely to extend into the future. At the same time, the unlocking of wealth effects should help the consumer.”

The real challenge for China’s economic future is how to avoid much of its investment going into unproductive areas like finance and property that have now led to serious problems. And also in what way the growing contradictions between the state and capitalist sectors in China are to be handled in Xi’s third term.

In part two, I will deal with these issues.

The Anti*Capitalist Resistance Editorial Board may not always agree with all of the content we repost but feel it is important to give left voices a platform and develop a space for comradely debate and disagreement.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War