In light of the mass arrests of those supporting the Palestine Action Group, it is useful to compare a previous wave of mass non-violent civil disobedience – the Committee of 100 in the early 1960s.

The Committee was a spin-off from the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), focusing public attention on the danger of nuclear war at a time when the Cold War nearly escalated into nuclear conflict over the Soviet Union’s siting of missiles in Cuba. Its founders were frustrated that CND’s large demonstrations were not producing rapid results.

The organised radical left – from the Communist Party leftwards – was not directly involved, but anarchists and pacifists became its main organisers. The Committee helped accelerate the radicalisation of activists, a process which, half a decade later, was inherited by the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign – whose main beneficiaries were the revolutionary left.

The chief organiser of the Committee of 100 was the late Ralph Schoenman, an exceptionally capable personal secretary of world-famous philosopher Bertrand Russell. Russell became the movement’s figurehead and, despite being 89, participated in sit-down demonstrations.

The 100 people who pledged to take part in civil disobedience included a stellar list of cultural personalities. Playwrights included John Osborne, Shelagh Delaney, and Arnold Wesker; visual artists encompassed Augustus John and Christopher Logue. Others included Marxist art critic and cultural theorist John Berger, film director Lindsay Anderson, jazz singer and all-round performer George Melly, and prominent CND campaigner Pat Arrowsmith.

Into Action

The Committee’s first action was a sit-down outside the Ministry of Defence in Whitehall in February 1961. They gathered 2,000 pledges to join the civil disobedience, and a still greater number took part, with hundreds more demonstrating nearby. Reflecting hesitation in Harold Macmillan’s Tory government over firm action, no arrests were made. A second sit-down in Parliament Square in April saw a change in tactics by the authorities, with over 800 people arrested and charged with obstruction of the highway and breach of the peace.

The third mobilisation took place in September 1961. Alongside a sit-down in Trafalgar Square, for the first time a nuclear base – the Holy Loch submarine base in Scotland – was targeted. This sent alarm bells ringing in government. Civil disobedience in and around nuclear bases shone a spotlight on the secret nuclear state and its preparations for war. Later demonstrations targeted US nuclear bases in Britain, generating international publicity and embarrassing the British government.

More than 1,300 people were arrested on these occasions, marking an escalation of confrontation between the state and the anti-nuclear movement. Thirty-seven people refused to be bound over to keep the peace and received one- or two-month prison sentences. Bertrand Russell was given only a token seven-day sentence.

Mass Sit-Downs and Repression

In December 1961, a further demonstration took place outside the American nuclear bomber base at Wethersfield in Essex. More than 800 arrests occurred. Six of the main organisers – Pat Pottle, Ian Dixon, Trevor Horton, Terry Chandler, Michael Randle, and Helen Allegranza – were charged with conspiracy and breach of the Official Secrets Act.

The men received 18-month jail terms, while Helen Allegranza was sentenced to 12 months. The significance of this trial was that the Committee had encouraged and planned a trespass at the base, interfering with its normal operations. This presents a specific parallel with the banning of Palestine Action by the Labour government today.

Modern Comparisons

If we compare the Committee of 100 with later direct action organisations like Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil, the numbers arrested and the charges they faced were broadly similar. Two things have changed, however: a) the passing of the Crime and Policing Act and b) the use of terrorism charges against demonstrators holding up placards in support of the Palestine Action Group.

These measures represent a much more all-round challenge to the right to protest than did the repression of the 100. The Committee of 100 experience showed how the dramatic effect of direct action can be used to spotlight issues. But it is only one tactic in the range that radical and anti-capitalist movements will need to use, none of which should be fetishised.

Crisis of Perspective

The Committee of 100 represented part of the radical wing of the anti-nuclear movement. It demonstrated the radicalisation of many prominent intellectuals and artists and deepened understanding of the role of the police and state repression.

However, the anti-nuclear movement was blindsided by the signing of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty by the US, Britain, France, and the USSR in 1963. The Conservative Party used this against the movement, running a newspaper ad showing a man sitting with a “Ban the Bomb” placard, captioned: “Meanwhile, the Government has signed the Test Ban Treaty.”

No sooner had the Committee managed to pull off several days of mass civil disobedience (and mass arrests) than it faced the obvious question – “What next?” In February 1962 another demonstration was held at Wethersfield, and on April 9 a new round of demos and sit-ins was held nationwide. This resulted in a total of more than 1,000 arrests.

In a sense, this was the high point of the Committee’s activity. But it also highlighted an underlying stalemate: how could such a widespread mobilisation be bettered? How many people were prepared to be arrested? Even if most convictions did not result in imprisonment, the disruption caused to individual lives was significant. And non-custodial sentences generally involved being ‘bound over’ to keep the peace – i.e., not taking part in further demonstrations for a year.

It was in the context of these debates that Bertrand Russell resigned as the Committee’s chair. In November, a broad series of demonstrations during the Cuban Missile Crisis were organised – doubtless supported by 100 activists, but bypassing the Committee as an organisation. The 100’s objective of highlighting the role of US bases and the nuclear secret state had been achieved.

In November 1962 CND underwent an upsurge, protesting against the nuclear war danger over the Cuban Missile Crisis. But the anti-nuclear movement was again blindsided by the signing of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963. The 1964 Aldermaston March was notably smaller. From the platform in Trafalgar Square, CND Vice-Chair Stuart Hall said: “If CND is dead, then I’m looking at 20,000 corpses” – although in reality there were closer to 10,000. Offstage, the first preparations were already underway for the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, which would briefly take CND’s place in mass anti-war mobilisation.

CND re-emerged spectacularly in the 1980s, leading the campaign against the siting of American Cruise and Pershing missiles in Britain and other European states. In 1984 it organised a demonstration of 400,000 in central London.

Legacy and Parallels

The Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 damaged the United States’ image and fuelled hostility to American imperialism on the left, especially in universities and colleges. The new radicalism outflanked the Communist Party, which clung to its cautious “peace talks” line on Vietnam. By 1966, the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign was overtaking the CP’s British Council for Peace in Vietnam.

The Committee of 100 was never banned, nor accused of terrorism. But the state, under Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and Home Secretary R. A. Butler, used long-standing conspiracy laws to strike at its leadership.

By the late 1960s it was difficult for radical and democratic mass movements to avoid using defensive levels of force. The American Black liberation movement faced huge amounts of police and vigilante violence. The anti-war movement and student occupations often faced brutal police responses, leading to defensive violence. ‘Self-defence is no offence’ was a more influential slogan than strict adherence to total non-violence.

The Committee of 100’s repression took place in a Britain still governed by a residual liberal consensus. We now live in a different world – one where liberalism has lost much of its moral compass, and the state’s routine use of law and force to suppress dissent is entrenched. The recent branding of Palestinian solidarity marches as “hate marches” by Tory Home Secretary Suella Braverman and others helped to set the stage for this repression.

Sequels

“Spies for Peace”

In 1963, during CND’s annual Aldermaston March, a group of anonymous activists – later known as the “Spies for Peace” – revealed the existence of a network of secret Regional Seats of Government (RSGs) underground bunkers, from where top army, police, and political personnel would administer Britain after a nuclear attack. One such RSG was at Warren Row near Reading, close to the Aldermaston March route. Hundreds of demonstrators split off to surround and expose the RSG, a huge embarrassment for the Conservative government.

The George Blake Escape

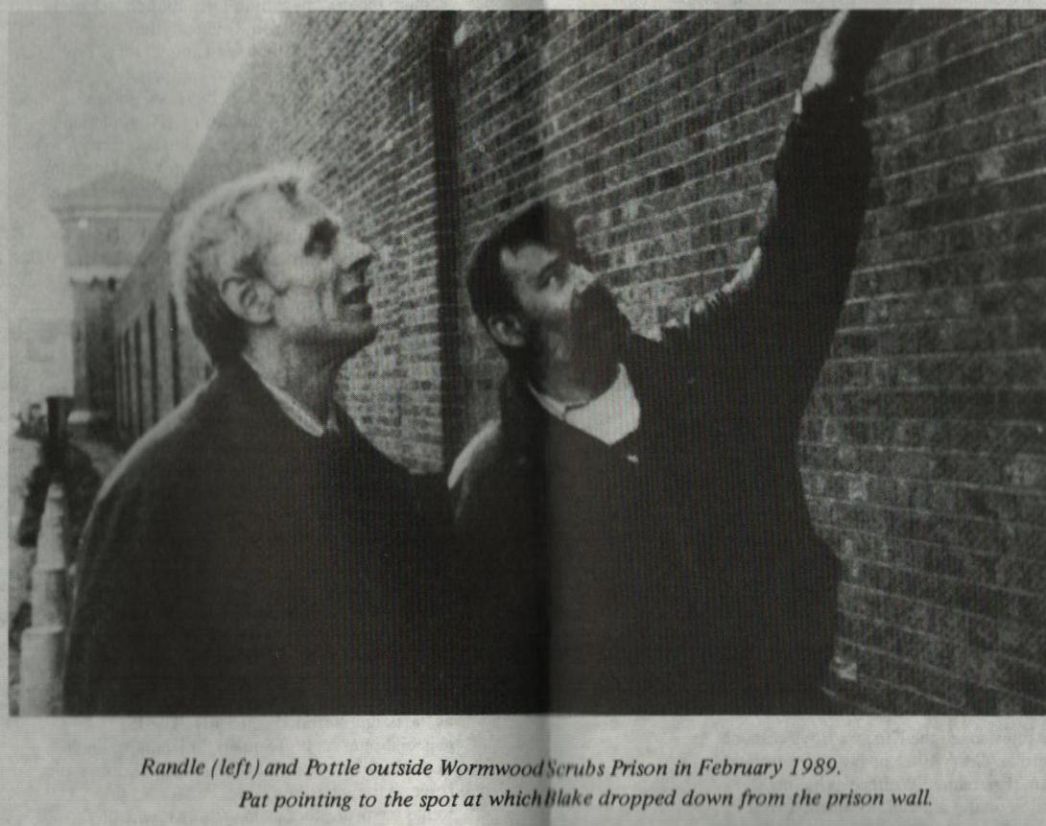

An unexpected outcome of the imprisonment of the six “conspirators” was that Pat Pottle and Michael Randle shared Wormwood Scrubs prison with George Blake, a British intelligence officer convicted of spying for the Soviet Union. Because of his position as an MI6 officer, Blake received an exceptionally severe sentence – 42 years. Randle and fellow activist Sean Burke, convinced of the injustice of this sentence, organised Blake’s escape. Randle transported him to the East German border, where he was met by KGB officers and smuggled into East Germany and then to Moscow.

A bizarre further sequel was the 1991 publication of a book by Michael Randle and Pat Pottle in which they openly described how they engineered their George Blake escape. Probably the state already knew of their involvement, but preferred to let sleeping dogs lie. But the publication of the book was a provocation they could not ignore, and they were tried at the Old Bailey. They admitted what they had done, but pleaded not guilty on the grounds that Blake’s sentence was unjust. The judge ordered the jury to find them guilty, but the jury refused and they were released – to widespread amazement.

A detailed account of the Committee of 100, by key participant Michael Randle, can be found here

Art Book Review Books Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 EcoSocialism Elections Europe Fascism Film Film Review France Gaza Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Palestine pandemic Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War

Socialist Challenge, a newspaper supported by Fourth Internationalists in Britain, published an excellent pamphlet detailing the history of the early Committee of 100 and CND etc, by Julian Atkinson and Tony Southall in 1980-81 “CND 1958-65 Lessons of the First Wave”. Available here: https://tinyurl.com/5n9449jw Tony Southall was an active Fourth Internationalist, a member of the Committee of 100 and at one point its secretary. He spent the last years of his life living in Glasgow and was active as Secretary of Scottish CND, obituary here: https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article423

My student landlady, Mary Ringsleben, was a member of the Committee of 100, and a friend of Pat Arrowsmith. She was also the secretary of Leeds CND, and signed me up promptly when I moved in. When I dropped out of university (not having chosen to go there anyway), I was recruited to her staff running the Leeds University Publications office, where I learnt proofreading, copy editing, and for a while I was on the CND editorial board. I remember her main advice ” If sent to prison, always ask for vegetarian food. It’s more edible”. Pat Arrowsmith once planted some bulbs in a prison garden in the CND symbol shape when told to plant them, according to Mary. I don’t know if she was still there when they flowered!