Anti-Capitalist Resistance condemns the atrocities committed by Hamas on 7 October. It does not hesitate to do so because it embeds that condemnation in an analysis of how these attacks came to take place, the conditions of occupation and mass murder over the past 75 years by the Israeli apartheid state. We understand why the first response of the anti-imperialist left on 7 October, and before the scale of the violence was apparent, was to hail this as the action of “freedom fighters”.

However, we were clear from the start that Hamas is not a progressive organisation, and its government of Gaza and military operations have always been functional to Israel; Netanyahu has many times argued that one effective way of weakening Fatah and the Palestinian National Authority, PA, would be to promote and even finance Hamas. It is also much easier to close ranks and unite the nation against monsters, including those you have created, than to negotiate with reasonable men in suits.

Condemning Hamas

That poses a political and ethical question for us when we are repeatedly told to “condemn Hamas”. What exactly is it we are condemning if we tell them to keep focused on the obvious monsters rather than the pathological state structures that need and feed them as enemies, and who uses that demonization of Hamas in order to pull people on side, on the side of Israel against the Palestinian people?

Condemnation in the field of politics, at least, is always part of a series of assumptions that are linked together in dominant ideological ways of describing the world. That ideological framing of politics is something that carries with it another series of courses of action. Those ideological ways of describing the world, or ideological frames, are held together in a language that is organised and independent of our will. We have to organise collectively not only to change the world but to forge a different way of speaking about it, which is with the oppressed rather than with the oppressors.

Part of the problem is that whenever we speak or write, our words are immediately chained together with other words and phrases, and they will be heard or read in conditions and with meanings we cannot completely control. At least, it always requires a lot of effort to argue and clarify, and when our words are quoted and quoted against us, there is sometimes little space to do that. So, when we are repeatedly told to condemn Hamas, we need to know in what context and for what purposes that condemnation is being demanded to be repeated.

Speaking and writing and sharing

Condemnation does not happen in a vacuum, just as the 7 October attacks did not happen in a vacuum, but when we respond to the question “Do you condemn Hamas” or “Do you condemn the 7 October attacks,” it points the blame in one direction at an event that is wrenched out of context. The consequences of saying yes to that condemnation are too often that we fall in line with a way of treating the Palestinians confined to Gaza as being the cause, the beginning of the problem. The “yes” corrals us into an ideological framing of the situation. In some circumstances, that means saying yes, agreeing that you condemn, but finding space to step back and know what this is for.

“Condemnation does not happen in a vacuum, just as the 7 October attacks did not happen in a vacuum, but when we respond to the question “Do you condemn Hamas?” or “Do you condemn the 7 October attacks,” it points the blame in one direction at an event that is wrenched out of context.”

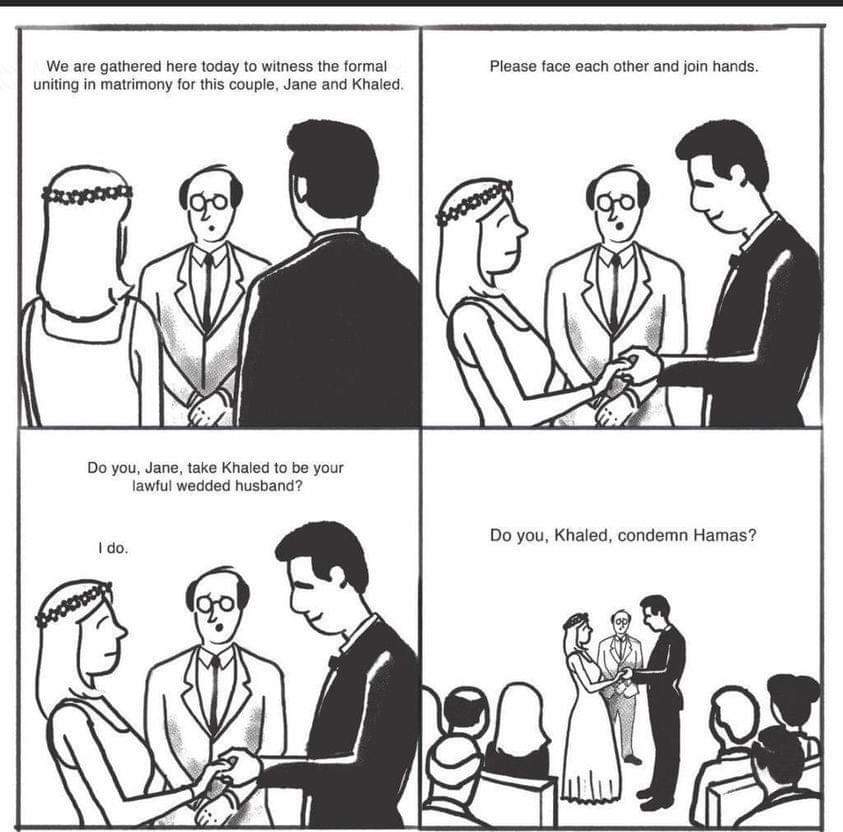

This is a problem that is made worse by the “liking” and “sharing” of stuff on social media. What, for example, if we liked and shared the cartoon that shows Jane and Khaled getting married where the official says “Do you, Jane, take Khaled to be your lawful wedded husband?”, and Jane says “I do”, and then the official says, and this is the punch-line, “Do you, Khaled, condemn Hamas?” What this cartoon does is precisely step back and make us think about what the repeated demand to condemn is tying us into. But then there is a little trap because of the uneven playing field of discourse around “condemnation”: someone who shares this could be asked, “But does that mean you don’t condemn Hamas?” Here you see the power of the condemnation discourse to condemn you for not falling into line with it. Things we say have a time and a place, and both of those things, time and place, change in ways we cannot ourselves determine as individuals.

Description and action

Now “condemnation” works not only as a description of the world, and it is obvious that it is not a neutral description of the world, but as a statement that does something, it is meant to have effects in the world. It is what students of language call a “speech act”; it is like when a judge says “I sentence you to death”, and what they say is not simply describing something that will have effects. And this “condemnation” speech act is part of a wider discourse or narrative in which there is “if this, then that” logic at work. If you really condemn Hamas, for instance, then you should necessarily support Israel, which claims they are doing the logical thing.

We can also notice something else about the way this is working now, in this current case. The call for condemnation re-centres things so that the perpetrators of the horrors of the last 75 years, that is, the Israeli state, are turned into the ones that we should, it is assumed, be speaking with and for. To agree that we condemn Hamas and to leave it at that, to say nothing more about it, is to continually refocus things from the standpoint of the Israeli state. To disentangle what we are being made to say when we say we condemn Hamas is sometimes difficult.

More than that, you need to notice who is given the right to condemn and who is not. This, again, is not a level playing field of discourse; a judge can condemn you to death because of their rights to speak in that way, because of their status and their power. And those who “condemn” bad things are speaking from a status that gives them the right to do that; “condemnation” is a speech act expected of those in power. To condemn is the kind of thing you expect from the UN, governments, or speakers with power, not the kind of thing that is heard as serious when it comes from a Palestinian in Gaza, unfortunately.

So, when you “condemn,” you also re-centre the debate around those in a position of power with the status to declare such things. “Condemn” is to claim a position, to re-focus things on that speaker rather than look carefully at what is happening, and the best way of describing it is part of progressive collective action. That collective action then changes the discourse we share to make sense of the world.

Traps and time

To give another example from this current situation, which is now clearly mass murder in Gaza, we could respond to the claim that the Israeli state is defending itself by saying that it is actually the Israeli state that puts Jews in danger. Israel cares little for the lives of the hostages in Gaza, and Netanyahu has explicitly refused ceasefire and hostage release negotiations, and it cares nothing for the lives of the conscripted IDF force soldiers, and it puts the lives of Jews at risk around the world because there is a deadly and mistaken ideological assumption made that speaks of Jews and Israel in the same breath, as if there were not many Jews who refuse to support Israel.

The danger is that this response flows into a discourse or narrative that works as a series of speech acts; that is, the danger is that it both re-centres Israel and its citizens as if they are the only ones we are concerned about. Yes, we are concerned, and resistance to the Israeli state will need to come from Jews as well as Arab citizens, and the state knows this well, which is why it criminalises the “boycott within” campaign and cracks down on anti-war protests.

“The danger is that this response flows into a discourse or narrative that works as a series of speech acts; that is, the danger is that it both re-centres Israel and its citizens as if they are the only ones we are concerned about.”

How we speak of that threat to the lives of Jews that the Israeli state poses is also important—it could so easily and unfortunately be spoken or heard as a threat, for instance, and care has to be taken about how that consequence of Israeli state action is noted—and that is why solidarity includes combating any instances of antisemitism, including in the anti-war movement. Now the task is to build solidarity and work to build it, acknowledging the contradictions.

Again, we need time, and make sure we have time together to collectively work through how we speak about these things so we don’t simply give a kneejerk response that locks us into ways of describing the world that are harmful to us and those we are in solidarity with. So, the question of condemnation is intimately tied to the question of solidarity, and the political and ethical task we are faced with is how to make clear our solidarity with the oppressed and to acknowledge suffering caused by systems of oppression.

Solidarity

One way of doing this is to follow the watchword “unconditional but critical support”. We speak out against actions that are harmful and self-sabotaging, and we voice that “critical” support as an act of solidarity. We voice it as internationalists in alliance with whichever oppressed group we are championing and relating to, and we voice this “critical” support knowing that there are always deep contradictions and differences in political organisations as well as in the communities they believe they speak for.

“One way of doing this is to follow the watchword “unconditional but critical support”. We speak out against actions that are harmful and self-sabotaging, and we voice that “critical” support as an act of solidarity.”

That is precisely how it operates: as “unconditional” support, argument alongside and with the oppressed rather than as a demand that we will only support them if they agree with what we are saying, with our view of the world, with our political analysis. Unconditional but critical support means that we weigh up who we are agreeing with and, on what terms, when we condemn this or that supposed enemy. Condemnation is articulated in our discourse of resistance in a way that is embedded in solidarity.

Art (53) Book Review (121) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (80) Climate Emergency (98) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) EcoSocialism (55) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (57) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (70) Gaza (60) Imperialism (100) Israel (124) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (52) Labour Party (111) Long Read (42) Marxism (49) Marxist Theory (48) Palestine (169) pandemic (78) Protest (152) Russia (340) Solidarity (142) Statement (48) Trade Unionism (141) Ukraine (346) United States of America (132) War (368)

Just a thought, doesn’t speak directly to the unconditional but critical support but adds a nuance:

Who or what is speaking – Two condemns:

1.To condemn as a collective, as a State, on behalf of a political party, as a court, etc – might be a juridical a-contextual judgment, one made simply because there is good evidence a law has been broken. But can, of course, be done for political gain

2.To condemn – might be a personally held view that claims ‘I’ would never act like that.

Finklestein argues he cannot personally condemn Hamas because he doesn’t know how he would act in the context of Gaza’s last 16 years, to presume you know would after all seem arrogant.

https://open.substack.com/pub/chrishedges/p/the-chris-hedges-report-with-professor?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web