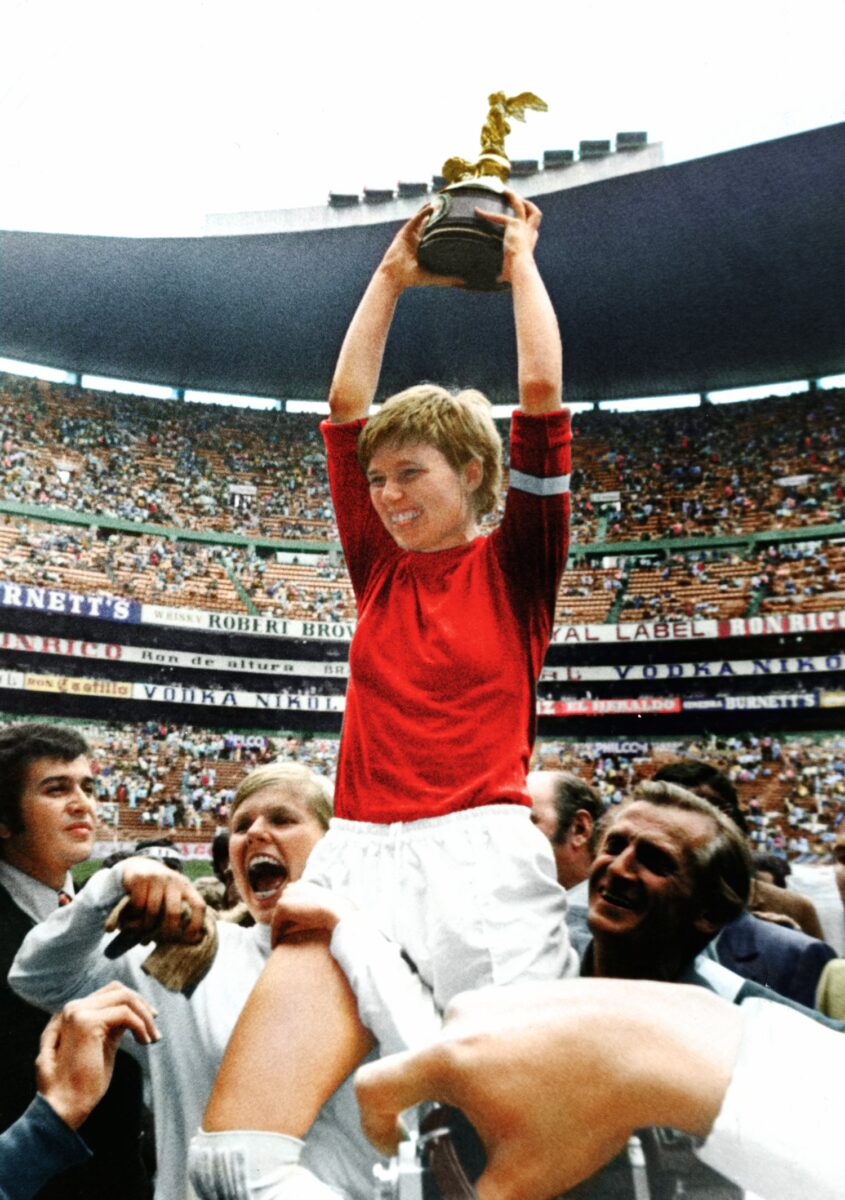

Brandi Chastein was a great US football player who helped her country win the 1991 and 1993 World Cups and Olympic gold in 1996. We meet her in the first scene of this film. She was handed a tablet and asked what the film was showing. She had no idea at all. The tablet was playing a clip from the first international women’s football tournament, organised in Mexico City. One hundred and ten thousand people watched the final between Mexico and Denmark; it remains the biggest crowd to watch a women’s match.

Chastein is not alone in her ignorance of this tournament. I consider myself quite a sports nut; my parents encouraged us to play lots of different sports, and I had no idea about this event. Asking around friends who know about sports, I got the same reaction. This event, like much else about women, has been erased from history.

At that time, women’s football was effectively banned from the official game. National and international governing bodies, composed almost exclusively of men and dominated by the ‘white’ European countries, had decreed that football was not an appropriate game for women. All sorts of sexist bogus arguments were made: it would threaten their childbearing potential, it would lower standards and be ridiculed, and that women had to raise families in the home. This was just at the beginning of the second wave of the women’s liberation movement; rights to abortion, divorce, equal pay, and so on had not been secured in most countries. Men’s football grounds and clubs were off-limits to women.

You may think that this ban was because only a tiny minority of women played football or that there was no point in developing the game because nobody would want to come and see women play. In fact, there had been hundreds of active amateur clubs set up in Britain at the beginning of the century. During the First World War, there was no men’s professional football. Women’s clubs played in front of thousands of supporters.

Some of these teams were linked to munition factories where women were working. There had been concerns about the number of women entering the workforce and what they might get up to in their spare time (e.g., some had moved away from home for the first time). Originally, it was more about morale and aiding production than filling gaps in the football schedule. Of course, the games became really popular, and so they did help fill the gap; however, the reporting was still of its period. They made the girls sound like a circus act at times!

The decision to effectively ban women’s football by the FA was about the retaking of a traditionally male space postwar (so a heavy dose of sexism was involved in everything that followed), but also about the growing professionalism of the men’s game before the war and early signs that the game could be really lucrative. The women had been raising money for charity or injured servicemen when they played their games, and there’s an argument that the FA was concerned that more questions would be asked about what they were doing with their profits.

There was a real basis for developing the game among women, but the governing bodies closed it all down after the end of the war. There was no historical inevitability about the progress of women’s sports. Choices were made and affected how sport and society developed.

The COPA 71 tournament had been set up by entrepreneurs who saw a way of following up on the success of the 1970 men’s World Cup that had been staged there. They could use the same spanking new stadiums that had been built for the previous year’s tournament, which featured the unforgettable Brazilian team led by Pele. There was a lot of focus in the promotion of the COPA on the ‘glamour’ of the women players, the short skirts and shorts, the hair and make-up, and so on. The male gaze and the novelty of seeing young women in a physical sport framed much of the publicity. In other words, the people behind the project were not women or feminists but capitalists out to make a lot of money. Needless to say, since the women were not professional footballers, they were not paid, which did lead the Mexican team to consider refusing to play the final, a threat that was later withdrawn under great pressure from politicians like the Mayor of Mexico City.

It is interesting to compare the contradictions of this tournament with how women tennis players fought to wrest control of their game from the governance of the male-dominated tennis associations. Billie Jean King got the best women players together and set up their own tournament circuit that was totally separate from the official one that favoured the men with much bigger prize money. King negotiated sponsorship from the Virginia Slims tobacco company to get the process started, but women led and organised the change. It is unsurprising that two great champions who have benefited from Billie Jean’s trail-blazing work, Serena Williams and Venus Williams, were the main producers of this movie.

We should also remember that the infrastructure of the women’s game in the six countries that participated was very undeveloped. There were no qualifying games to get into the COPA 71 final. The organisers chose the countries where they believed decent squads could be found. Although the games were transmitted live in Mexico and had extensive media coverage, they were not re-transmitted in Europe. So it is not surprising that the tournament passed under the radar of sports fans here and elsewhere.

What is true is that after the amazing spectacle of over 100,000 people seeing a women’s football match, the football authorities made no attempt whatsoever to build on that success by starting development programmes or providing resources. The ban preventing entry into existing clubs or grounds remained.

This film was only made possible because of the Mexican media’s intensive coverage filmed in colour; the previous year’s World Cup was the first to not be in black and white. The makers of this film then just had to search out some of the players who took part, and the documentary was good to go. A simple but effective narrative for the documentary was set up. We follow the progress of the tournament and news reports about it, but this is interspersed with contemporary interviews with some of the women who played, who are now mostly over seventy years young.

Apart from anything else, people love to see how we change over the years. You often see lifeline photos at birthday parties, and everyone looks at them. Watching these women today, you can still see the character and personality needed to go against the norm—the courage to follow their dreams. The Italians and the Mexicans still disagree about some of the dodgy refereeing that ensured the home team got into the final. Looking at the skills on display in the clips of the matches, you also wonder what further progress they could have made with coaching and the support women players get today.

We witnessed how this event was a pivotal moment in their lives. Women footballers come from working class backgrounds. None had taken a flight anywhere or stayed in such fancy hotels. Although they were not paid, they were treated well and feted by the Mexican public. Above all, the fact that they were the first women footballers to play in such iconic stadiums and in front of so many people has remained an element of pride down to today.

Nevertheless, they are rightfully bitter about the way their exploits made no difference at all to women’s football back home. One of the British women, Carol Wilson, talked about the sexist response she got when asked to say a few words at a Newcastle United reception. She was so upset about it that she hung up her boots and did not play again.

I liked the international scope of the film. We hear Spanish, French, and Italian throughout the film. You witnessed how women were discriminated against in all the countries. You could see in the Danish victory that progress for women varied to a degree; years of progressive social democracy there probably facilitated a better level of women’s football. The Scandinavian countries have a good record in women’s football despite their smaller populations. Today, the international game is much more competitive as infrastructure, resources, and coaching have advanced in many more countries.

The film finishes with Carol and some of the others attending the 2022 women’s Euros, won by the English team. They express a sense of satisfaction that their struggles to play eventually led to the much better situation today for women’s football. Today, if you get to play in the top league, you can make a decent living—still not equal to men—and matches at grounds like Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium draw crowds of more than fifty thousand. International tournaments like the Euros or the World Cup are now big events covered by the media worldwide.

[Thanks to RK for the additional points about the First World War and women’s football].

Art (53) Book Review (121) Books (114) Capitalism (65) China (79) Climate Emergency (98) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) Economics (40) EcoSocialism (55) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (56) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (70) Gaza (60) Imperialism (98) Israel (124) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (52) Labour Party (111) Long Read (42) Marxism (48) Palestine (169) pandemic (78) Protest (152) Russia (340) Solidarity (142) Statement (48) Trade Unionism (141) Ukraine (346) United States of America (132) War (368)