It is very difficult just to walk past this painting. Sharks circling, a massive storm, and the lone young black sailor facing certain death. We see the mast is broken, and the sail has gone. The man looks away from the sharks. Maybe he is desperately looking for another boat. His hand seems to be touching or grasping a sugar cane, and there are a number of other canes on the deck. Were they for sale or sustenance during the trip? Around the boat, the water is flecked with red. Have the sharks killed already? If you look carefully at the horizon, there is perhaps a glimmer of hope – the shadowy outline of a schooner can be seen through the storm clouds. But to the right of the horizon, we can also see a wind spout, which could also threaten the boat. The man’s expression – is it resolute or resigned to his fate? His posture suggests he is resilient still. The sea’s greens, greys, and turquoise blues are vividly painted. At the stern of the boat, you can clearly see its name, “Gulf Stream.”

This picture has been rightly considered the iconic work of Winslow Homer (1836–1910). It is given centre stage at the National Gallery exhibition and is on the cover of the catalogue.

While I was preparing this review, I happened to overhear an interview on Open Book, a BBC Radio 4 programme, with Barbara Kingsolver (who has written one of the best books on Trotsky’s final years). She said that great writers or artists do not lecture but let you into an interesting conversation where you can make up your own mind about the meaning of the work.

This picture, like many of Homer’s other works, tells a story. He painted mostly within the history painting and landscape genres. Homer himself wrote and commented on his paintings very little. Indeed, some of his fans were upset about the first version of this work because they did not like the uncertainty of the man’s fate. He responded sarcastically, saying you can tell “those ladies that he will be rescued and returned to his family and friends and live happily ever after.” In fact, he revised the painting for its final version in 1906 by including the ship on the horizon, restoring a modicum of hope.

There have been many interpretations of the painting. Some have related it to the theme of mortality, which is a recurring theme in his work. He was feeling vulnerable and alone after his father’s recent death. Most critics have directly linked it to the black experience of slavery. Homer was always concerned with conflict and humanity’s difficult relationship to nature. The Gulf Stream currents geographically facilitated the triangular slave trade. Sugar was one of the key commodities that European traders made their profits from. The booming market in Europe for this new sweetness depended on the sour brutality of the slave system. Homer was certainly familiar with Turner’s painting The Slave Ship, showing slaves thrown overboard. It was well known that sharks followed slave ships because they had learned that sick slaves were regularly thrown overboard. The picture was well painted after Reconstruction began after the American Civil War. As Homer alluded to in other works, the Reconstruction did not provide a promised land for black people. The man in the boat symbolises the difficulties facing black people at the time,

Homer was no radical, but he was broadly liberal and progressive for his time. He supported the Union side in the war, and he made his mark making print illustrations for Harper’s Weekly during the conflict. He came from a well-to-do New England family, albeit one with a father who squandered their wealth. His passion was his art, and he never married or had children. He spent a lot of time fairly isolated on Maine’s rugged coast. However, he did have some understanding and empathy for people, so he was one of the few people to actually paint black people in a relatively objective way.

Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, in an article that is included in the catalogue for the US show this July but which is inexplicably not included in the National Gallery, shows that there was a progression in Homer’s depiction of black people. There are a few “ministrelly” or “music hall” figures with exaggerated lips and eyes playing banjos, and the names of his pictures were changed to make them more acceptable to a white market. He tended to paint black women in the US context, and the racists felt particularly challenged by the black male. There is some ambiguity even with the later water colour pictures of Caribbean young black fisherman – are they homo erotic objectifications by a well-off white tourist of the black body? Some critics have speculated that Homer was gay; others just suggest he was asexual or wedded to his art. We do know that the artist was threatened with violence by white racists when he was down in the South for painting black people.

Several black artists today have recognised his contribution, whatever its limits. Kara Walker’s 2019 installation in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern included a direct reference to the Gulf Stream painting.

In the excellent film you can see in the exhibition, you can see another black male artist showing his own recreation of a Gulf Stream boat in a public installation.

During the Civil War, he made many prints, but he later developed paintings from his experience. He avoided the blood and gore of the battle scene – it is still the case that more Americans died in this war than any others. Instead, he showed soldiers, including black volunteers, at rest or focused on a lone sniper sitting across a branch. That one picture does capture the reality of war through its cold-blooded stillness. Homer said painting it helped him understand the murderous aspect of war. In this image, near Andersonville, 1865, he managed to capture the uncertainty of the conflict, particularly from the perspective of black people.

In the top left corner, you see the Confederate soldiers marching along with some captured Union men. The expression of the black women captures what must have been some fear and uncertainty about the course of the war.

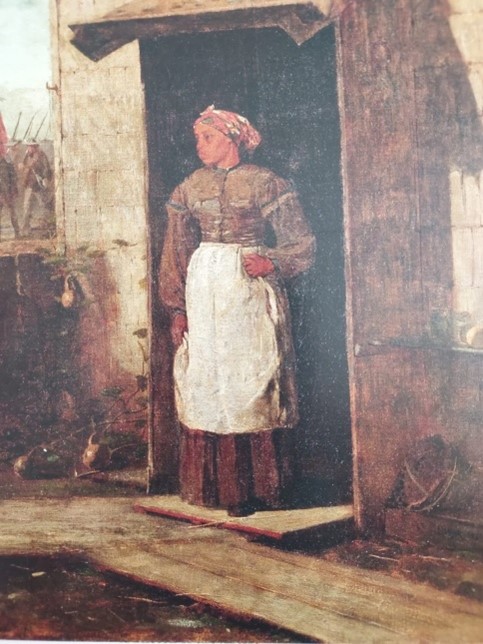

Several of his pictures address the problems of the Reconstruction period, when reforms were supposed to improve the conditions of black people in the South. A visit from the old mistress (1876), where the relationship is now between a boss and wage workers, we see class distance and tension etched in the faces:

This is much more powerful than the ambiguous, anodyne, but stunningly beautiful Cotton Pickers (1876), which was snapped up by a British merchant and was the only Homer picture seen in Britain at the time. Although the two women are not shown cheerily going about their jobs, the overall effect is one of lushness and warmth; the poverty is erased. It looks like a dreamy Whistler picture. You can understand why a British cotton merchant was enraptured with it. I suppose this picture sits alongside some of his other ones that reflect a post-war optimism about building a better America, such as the Veteran in a New Field with a glorious horizon of wheat to be harvested.

Homer was a fan of the sea’s power and beauty, so it’s no surprise that he chose the unfashionable fishing village of Cullercoats near Tynemouth for his year and a half in Britain. Apart from the landscape, he was attracted to recording, in some ways, the lives of the local community. He was particularly inspired by local women who had their own tasks in the fishing community as well as their maternal roles. They also had the risk and worry of losing their men at sea. He admired the everyday heroism of the life brigade – those who went out to rescue people. Lifeline, a painting in the show, pits you against a rescue at sea using the new breech pulley system. Using the techniques of classical art that he had picked up on an earlier trip to Europe, he turned these working class people into heroic, epic figures.

The Gale, 1883–93, depicting a woman and child on the coast, was a huge success for Homer. In the film at the National Gallery, you can see an interview with a proud relative of one of the women that Homer painted, who endorses his honest portrayal of her community. At the time such working class communities were not considered celebrating particularly

Although he retreated to a reclusive life in Maine, Homer escaped the worst of winter by going down to Cuba, Bermuda, and the Bahamas. Again, the sea and the local communities held his attention. You can see in the exhibition that these are nearly all watercolours. At the time, watercolours were seen as inferior to oil painting, but you can see that this was just a stupid prejudice of the academy. The colours and heat of the Caribbean leap off these pictures. He paints a lot of young men fishing or swimming in these paintings. These are not just romanticised holiday pictures; Homer includes subtle references to the continued colonial rule of the English in these parts. The union ensign can be seen on the right side of this photograph, The Bather 1899.

What a contrast to the darker, harsher colours of his Cullercoats pictures! There is a picture of the harbour in Santiago de Cuba, in Cuba, which was painted at the time of the war for independence against Spain. The USA was fighting Spain at the time, and the picture shows that the US Navy spotlighted the harbour entrance to prevent the Spanish from attacking the Cubans. Homer had the nose of a reporter for much of his life.

In his final years, he became more reclusive, and his art focused on pure seascapes. They lose their narrative and become almost abstract in their effect on the viewer. It provides a serene and moving final room in the exhibition.

The US exhibition was called Crosscurrents, and the National Gallery opted for Force of Nature. I think it is helpful to combine both. Homer was not just interested in nature. He was always interested in human conflicts and the relationship between us and nature. If you think of many of the European Impressionist painters of the same period, their work often engages less with social reality and conflict than Homer’s. He could not directly experience the struggles of black people in the US South, a fishing community in the North East of England, or black people in the Caribbean as an artist from a wealthy New England family. Nevertheless, his imagination and skills did manage to communicate a story in which we can reflect on those struggles.

Although there was a small exhibition of his work in Dulwich in 2006, this is the first major exhibition of Winslow Homer’s work in Britain. It is well worth discovering this American artist. Finally, I loved this picture from his British period. Pared down to a few colours and vertical blocks – it could be a Rothko work. – it’s all there: the force of nature and the dilemma of our human community, who have to live with it moving forward.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War