Source > Michael Roberts blog

15 May 2022

Last Thursday the $1.3tn cryptocurrency industry was hit heavily when ‘stablecoin’ Tether — a critical cog in the crypto market — briefly failed to maintain its link with the US dollar. A stablecoin is a crypto currency coin that is tied to an existing fiat currency, namely the US dollar, making it easy to switch (if expensively) between a crypto currency like bitcoin and an official currency like the dollar. Stablecoins are supposed to track real-world currencies and so play a central role in the stability of the broader crypto market by providing traders with a safe place to park their cash between making bets on volatile digital coins.

But last week that one-to-one parity between Tether and the US dollar was broken and Tether’s price in dollar’s fell, if only briefly to 96c.

A fundamental issue for all stablecoins is their resilience to conventional speculative attacks, analogous to attacks on fixed exchange rates. Tether’s accounts show that their cash reserves to back the dollar peg are only 4%, with most of the rest in risky dollar commercial paper. JP Morgan recently reported that the Tether stablecoin has no regulatory supervision or deposit insurance. So if people were unwilling or unable to use Tether tokens, “the most likely result would be a severe liquidity shock to the broader cryptocurrency market,” which could lead to everyone trying to sell at once.

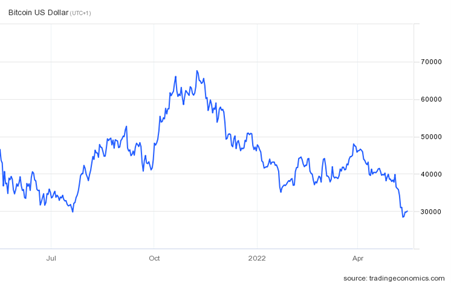

Tether’s wobble happened at the same time that the cryptocurrency market took a huge dive along with other speculative financial assets, like stocks and bonds, in what investors and traders now call a ‘bear market’. This proved, once again, that cryptocurrencies are not money, but just another form of speculative financial asset that will suffer when investment bubbles start to burst.

Tether is the biggest operator in the $180bn stablecoin market. There are 80bn Tether tokens in circulation, meaning it should hold $80bn in assets — a sum that compares with the biggest hedge funds in the world. But details around how those reserves are managed are scant, and not subject to audits under internationally recognised accounting standards. Last year, the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission fined Tether $41mn, claiming the company made “untrue or misleading” statements about its reserves.

The crypto crash was further amplified by another cryptocurrency, TerraUSD. It crashed in price against the dollar by 98%! Terra also calls itself a stablecoin, but it has little in common with Tether besides the goal of being worth $1. Instead of being backed by dollar assets, it is an “algorithmic stablecoin”, where its value against the dollar is determined by ‘decentralised’ decisions made by participants. Its value thus depends not on any dollar-based assets backing the stablecoin, as supposedly with Tether, but purely on the trust taken by the holders of Terra that it is equivalent to a dollar!

This is in effect a ‘Ponzi scheme’ where the value of the assets depends on enough people prepared to keep buying it when others want to sell and not on any underlying value of any commodity backing it. As one observer put it, “this seems like a house of cards because it is. The system relies on an active market, which in turn requires traders to believe they won’t get stuck holding the bag. If everyone sours on TerraUSD at once, the whole thing crumbles.” And it did.

All this proves what I have argued in previous posts. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are no nearer universal acceptance as money than when they first came on the scene. They remain part of speculative digital finance. They will not replace fiat currencies, where the supply is controlled by central banks and governments as the main means of exchange. They will remain on the micro-periphery of the spectrum of digital moneys, just as Esperanto has done as a universal global language against the might of imperialist English, Spanish and Chinese languages.

In the meantime, the crypto mining industry uses huge amounts of energy in the ‘mining’ of these currencies as computer assemblies needed for crypto mining now consume 0.55% of global energy production – about as much as a small country. All the hype associated with crypto obscures the fact that it is using millions of tons of coal, copper, rare earth metals and plastic. China effectively banned the mining and use of cryptocurrencies in late 2021 because mining was consuming so much energy and because of the speculative risks associated with crypto.

These big falls in crypto prices have exposed the failure of some emerging countries’ attempts to raise funds by launching national crypto currencies and by issuing crypto-currency government bonds. Take the El Salvador experiment. Three economists — Diana Van Patten of Yale, Fernando Alvarez of the University of Chicago and David Argente of Penn State — have recently published a study of bitcoin adoption in El Salvador. Their findings, based on a representative in-person poll of 1,800 Salvadoreans, suggest that outside of young, educated, tech-savvy men, durable interest in bitcoin has not materialised.

The Salvador government has offered all kinds of incentives to citizens to use crypto ‘chivo’ over the US dollar, which is in short supply: a $30 installation bonus, paid in bitcoin, worth 8 per cent of the monthly minimum wage; a discount at the country’s biggest petrol stations, only for chivo users; a 150mn national fund to subsidise bitcoin-related fees; a rollout of 200 bitcoin ATMs in El Salvador and 50 more in America; legal tender status, so firms are required to accept the crypto currency and taxes can be paid in bitcoin. But none of this has worked. Most Salvadorians continue to use the US dollar. The study found that “the most important reason for [people who knew about Chivo but did not download it] was that users prefer to use cash. This was followed by trust issues — respondents did not trust the system or bitcoin itself.”

Speculation is inherent in capitalism, but it increases, as other financial activities, in times of economic malaise and crises, i.e. when profitability falls in the productive sectors and capital migrates to unproductive and financial sectors where the rate of profit is higher. This is the reason for the emergence and rise of the crypto market. What the fall of this market now shows is what happens when investors start to expect a fall in profits from an impending slowdown and even recession in the ’real’ economy.

The Anti*Capitalist Resistance Editorial Board may not always agree with all of the content we repost but feel it is important to give left voices a platform and develop a space for comradely debate and disagreement.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War