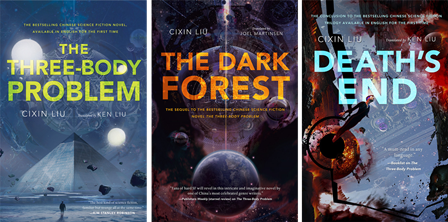

Liu Cixin, a darling of the Chinese state whose books are heavily promoted and very popular, may be surprised to hear that his ‘Three Body-Problem’ trilogy, which is named after the first book but which is formally correctly known by the very indicative title ‘Remembrance of Earth’s Past’, is going to be turned into a Netflix series.

This is not going to be easy because Liu Cixin writes in the genre of ‘hard sci-fi’, that is, the kind of science fiction writing that is not so much concerned with soft social and moral problems that the Star Trek franchise tinkered with but with technological mind-blowing stuff that makes the human species look very small, very insignificant. There is, nonetheless, plenty of social and political stuff woven into the trilogy, and some potent ideological motifs at work, the kind of stuff that makes this work chime with the agenda of the state.

The first thing to notice about the ‘remembrance of the past’ claim is that the first book in the trilogy, The Three-Body Problem, does not dig very far into the past at all; mainly dwelling on the brutal treatment of near relatives of key characters during the Cultural Revolution, something that is very obviously portrayed as a bad thing. An astrophysicist is beaten to death during a ‘struggle session’. Brutal and manipulative the Cultural Revolution may have been, but that, for Liu Cixin, is not the main problem with it because, as he makes clear in the next two books, a measure of brutality – and the number of deaths as we go through the trilogy is truly mind-boggling – is necessary, even valuable for technological and social advance.

Order

The main problem with the Cultural Revolution as seen in the first book is that it is chaotic and random, and here the first lesson of dystopian science fiction of this kind is spelt out in gruesome detail; order is bad but inevitable, but disorder is worst, and you need to report any instances of it to the authorities.

In fact, the ‘three-body problem’ is precisely itself about disorder, about the instability of a ‘three-body’ star system in which three solar bodies are orbiting each other and producing extremes of heat and cold. The question that needs to be faced by humanity is how they should respond when, on a very long but ineluctable time-scale, ships seem to be coming on invasion-course from that unstable star system towards our own, towards earth. By earth here, read China, and China and Chinese protagonists are at centre stage through the three books. This rebalances, in a progressive way, the usual assumption in Sci-Fi writing that the Western world is the technologically advanced centre of our planet and representatives from other cultures should merely come onto the stage as bit parts (think Chekov and Sulu).

the first lesson of dystopian science fiction of this kind is spelt out in gruesome detail; order is bad but inevitable, but disorder is worst, and you need to report any instances of it to the authorities.

Suspicion

The second book in the series, The Dark Forest, deepens the China-centric focus on earthly progress when under threat, with a repetitive meditation on what the consequences might be of sending a message out from this planet to other possible civilizations. The premise of the ‘dark forest’ hypothesis is that the universe, like a forest, is an irredeemably hostile place. While it is tempting to imagine that other forms of life in far-away star systems are necessarily more technologically advanced and so more socially advanced, and so likely to be pleased to hear from us because they look forward to visiting us and making friends with us (the Posadist position, for example), it is actually more likely that other civilizations are more brutal and will be intent on colonising us.

The lesson of the ‘dark forest’ is that you should definitely not signal your presence in the world to others, but instead keep yourself hidden; hidden and silent is the safest option. This message is replicated at different levels of the trilogy, ranging from keeping quiet during periods of social turmoil like the Cultural Revolution, to keeping quiet about what technological progress you are making in relation to the West, possibly hostile countries outside China (a historically understandable take on things), to contact with aliens. Assume they are out to destroy you and attack first.

The lesson of the ‘dark forest’ is that you should definitely not signal your presence in the world to others, but instead keep yourself hidden; hidden and silent is the safest option.

The trilogy unfolds through the second and third book over literally millions of years, a span of time that also marks it as ‘hard sci-fi’, and it is here that the dystopian aspect is drummed home. Reading the trilogy is like being drawn into a nightmarish march forwards that is inevitable and bloody, marching to the beat of a drum that you do not control, and harnessing yourself, adapting to technological change that, you realise somewhere along the way, will never promise utopia, will never perhaps even promise a better life.

Obedience

Hard sci-fi here is also hard life, a hardening of our stance towards others – suspect them, and be all the more suspicious the more different they are – and hardening relations of self-control, and ordered social relationships, along with adherence to authority. There is, for example, a lull in the narrative in the middle of the trilogy where there are signs that things are going soft, that things are going wrong, that the human race has lost its edge, is not on a winning streak against the alien forces. The key sign of this is a breakdown in gender relations, specifically that women become more masculine and men become effeminate, a moral-political message that will play well with the Chinese state now, and not so well with the LGBTQI+ communities who are seeing each and every space to contact each other shut down.

Nature

But, and here is the good news from Liu Cixin, the healthy natural balance between male and female reasserts in book three, Death’s End, and the onward march to the future is restored. This is not a matter of choice, and personal choice is also something treated with a great deal of suspicion in the trilogy – even almost as bad as an alien invasion – but of necessity, and so we have a quasi-Confucian concern with respect for your elders and betters combined with awesome technological expertise, the triumph of technological reason over everything else. If the encounter with the universe will show us anything, the trilogy seems to be saying, it will show us what our deepest nature is as obedient well-behaved and grateful servants to a higher purpose.

Whether Netflix will balance this all out with a liberal-individualist concern with dialogue and a pretence that decisions are taken for the good of all, or whether it’ll glory in the unending subjection of human beings to a machine-like future, bewitched as they are glued to a screen that replicates in their leisure time the lives they lead while working, remains to be seen.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women