How should we interpret the results of the EU parliamentary elections?

The first observation: in the EU elections held in all 27 member countries between 6 and 9 June 2024, voter turnout was once again very low. The average for the entire European Union was 51%. But keep in mind that countries where voting is compulsory also figure into the calculation of that average – for example Belgium, where voter turnout was 90%.1 Without those countries, the rate of participation in the election would drop below the 50% mark. Out of the 27 EU member countries, 15 had a voter turnout of less than 50%. And the countries who recently joined the EU the rates were extremely low. In Croatia the voter turnout was only 21.35%. Croatia only joined the EU in 2013, and did not become part of the Eurozone and the Schengen Area until 2023. In Lithuania, which joined the EU in 2004, the voter turnout was 28.35%. For the two other Baltic republics, the rate was 34% for Latvia and 37.6% in Estonia. The other countries where participation in the election was low are: the Czech Republic with 36.45%, Slovakia at 34.40%, Portugal with 36.5%, Finland with 40.4, Bulgaria with 33.8% and Greece with 41.4% (and remember that voting is compulsory in the latter two!). Italy’s rate (48,3%) was six percentage points lower than in 2019. In France, the turnout was 51.50%. Among the major countries of the European Union, only Germany is well above the 50% turnout mark, with 65%.

In Croatia the voter turnout was only 21.35%

Conclusion : the majority of European Union citizens have no enthusiasm for the EU institutions and don’t see the point in exercising their right to vote. Citizens of the countries of the former Eastern Bloc or Southern Europe, who were full of hope when their countries became part of the EU or later the Eurozone or the Schengen Area are clearly disappointed by the promises of improved quality of life that have not come true. Hopes of progress in the area of social rights have not materialized – quite to the contrary. Whilst it sometimes adopts a few relatively positive resolutions, the European Parliament has no real power. It is the EU Commission and Council who make the real decisions; and the major countries like Germany and France have decisive influence there. And don’t forget the coercive role played by the European Central Bank on several occasions, as in the case of Greece in 2015, where it used its power to destabilize a government that was not docile enough in following the policies set by the EU’s real leaders. Those policies are forced on the populations by the governments of the countries who dominate the EU economically and politically and by the major private corporations, in particular big private banks and investment funds. Citizens also realized during the coronavirus pandemic (2020–2021) that the EU’s leaders were incapable of adopting health policies that could protect them effectively. And since then, the EU has done nothing to improve the situation structurally – refusing to put in place a pharmaceutical industry capable of responding to a new pandemic, refusing to support the proposal of 135 countries of the Global South to suspend application of patents, barring universal access to vaccines and instead supporting Europe’s arms industry by increasing military spending.

The conservative Right and the extreme Right have emerged greatly strengthened

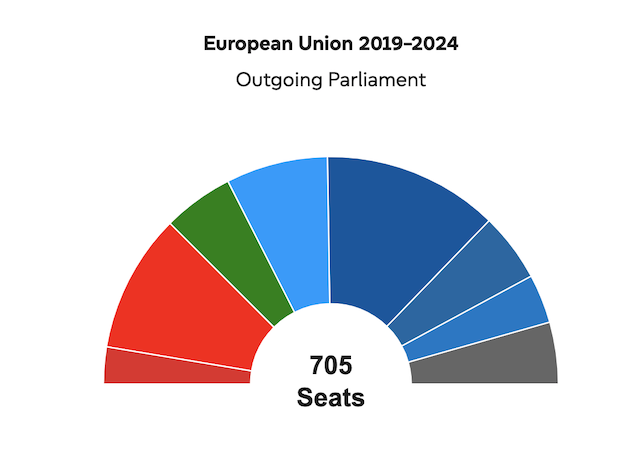

Second observation: political forces of the conservative Right and Far Right have emerged greatly strengthened. Political groups who promoted themselves as being centrist or centre-right, despite their conducting hard-right policies regarding migrants, candidates for asylum and the accelerated remilitarization of Europe, are reeling from heavy losses in certain cases. That is especially true of the group centred around the party of Emmanuel Macron, Renaissance, which lost 10 seats, dropping from 23 to 13. Another example is Open VLD and the Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo, who lost half their seats. Voters prefer the original (the Far Right or hard conservative Right) to a pale imitation.

The other big losers are the European Greens, who paid for their compromises regarding climate change, the environmental crisis and managing migration and the right to asylum. They also paid for their support for the remilitarization of Europe and alignment with NATO. On certain occasions the Greens have played a fundamental role in forming majorities in the Parliament and the approval of the principal measures of the 2019–2024 legislature (the European Green Deal, the remilitarization of Europe, the Migration and Asylum Pact, etc.). In their respective countries, for example in Germany and Belgium, the Greens have been accomplices to rightist policies. As Miguel Urban writes: “While in 2019 they had won recognition, to a certain extent, as forces for renewal and modernization of a bipartisan governance that had become ineffectual, their inability to meet expectations caused them to pay a high electoral cost.”2 [2] The European Greens group lost 17 seats, going from 71 to 54 seats. The Greens group was the fourth-largest one in the European Parliament, ahead of the two extreme Right groups ECR and ID (see below). It is now in sixth place. The two extreme-Right groups are now ahead of them.

The dominant group in the European Parliament, the European People’s Party, in which the CDU-CSU of Ursula von der Leyen and the Spanish PP predominate, is tempted to reach out to Giorgia Meloni and her extreme-Right party

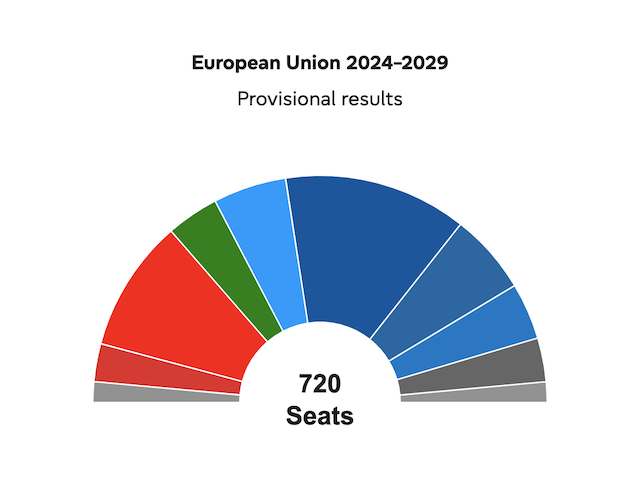

Third observation: the coalition of three parliamentary groups that governs the European institutions has held on to a majority, even though it has dwindled from 417 to 406 seats, and can continue to govern the EU. That coalition includes the European People’s Party; the “social-democrat” group of Socialist parties; and Renew Europe (which includes Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance, Open VLD of Alexander de Croo – who resigned on the evening of the election following his party’s defeat –, and the VVD of Mark Rutte, Holland’s ex-Prime Minister. But the dominant group in the European Parliament – the European People’s Party, in which the CDU-CSU of Ursula von der Leyen and the Spanish PP predominate – is clearly tempted to reach out to Giorgia Meloni and her extreme-Right party Fratelli d’Italia (a member of the ECR parliamentary group) in order to include Italy in Europe’s governance. Meloni, for her part, is bolstered by her own electoral success on 9 June by the growth of the extreme Right parliamentary group, which she leads and which has gone from 69 MEPs to 83. She is demanding a place among the among the top EU leaders, arguing that Renew Europe has dropped from 102 to only 75 MEPs. We’ll know in late June whether she gets her wish.

The “radical Left” group has gained strength overall, going from 37 seats to 39

Fourth observation: the “radical Left” group – the smallest group in the European Parliament – despite losses in some countries such as Portugal, where both the Left Bloc and the PCP lost almost half their votes and seats, has gained strength overall, increasing from 37 to 39 seats. It could grow further, as the Non-attached Members and independents, who represent more than 80 MEPs, could join it. Beyond the composition and the number of the radical Left group The Left, certain successes should be noted. La France Insoumise, for example, did well compared to its 2019 results: the party went from 7 to 9 MEPs, with almost 10% of the vote. We should also add the results of the radical Left in Belgium, with the Workers’ Party of Belgium (PTB) doubling its score and its representation in the EU Parliament (see below). Italy is also a case in point, where the Green and Left alliance reached nearly 7% of the vote and won two EU Parliament seats (see below).

Fifth observation: the crisis of political systems continues to be reflected, in addition to the strengthening of the far Right, by the emergence and success of short-lived lists who take advantage of their impact on the social networks and the voters’ desire for alternatives outside traditional or even “classic” far-Right political parties. Two examples of this phenomenon: the list of Fidias Panayiotou, a 24-year-old Cypriot TikToker, which ranked third and won a seat in the European Parliament with almost 20% of the vote, and Alvise Pérez, the candidate of Se Acabó La Fiesta (The Party is Over), one of Spain’s new parties, which won three seats with 800,000 votes. Alvise Pérez is very active on the social networks Telegram and Twitter / X, where they spread clearly right-wing oriented fake news. Recently, X withdrew his access to the network. He is targeted by several criminal proceedings for defamation and hopes to take advantage of his status as an MEP to dodge them during his term of office.

How much stronger has the far Right become?

The far Right has succeeded in becoming the leading political force in Italy (Fratelli d’Italia), France (RN), Hungary (Fidesz-Hungarian Civic Union), the Netherlands (Geert Wilders’s PVV – Partij voor de Vrijheid) and Austria (FPÖ)

The two far-Right EU Parliament groups, which together numbered 118 MEPs in 2019, have emerged stronger from the 2024 elections. They now have 134 MEPs. The total is 149 if we include the 15 MEPs from Germany’s far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), which was expelled from the Identity and Democracy (ID) group dominated by Marine Le Pen’s RN in May 2024, following pro-Nazi statements by its main candidate during the European election campaign. It should be noted that on 9 June 2024, AfD became the second-largest political force in Germany with 15 MEPs, whereas in the 2019 European elections it was in fifth place with 9 seats. If we add Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz-Hungarian Civic Union party, which came out on top in the Hungarian elections and won 10 seats, the total would be 159 MEPs.

Indeed, it should be noted that a number of non-attached members and independents are also likely to join one of the two far-right parliamentary groups. The far Right has succeeded in becoming the leading political force in Italy (Fratelli d’Italia), France (RN), Hungary (Fidesz-Hungarian Civic Union), the Netherlands (Geert Wilders’s PVV Partij voor de Vrijheid) and Austria (FPÖ). And it is the second-largest force in Germany (AfD) and Belgium (thanks to the success of Vlaams Belang in the Flemish part of the country, which is in second place behind the NVA, a radical right-wing party). The far Right has grown steadily in Europe since the beginning of the century. As Miguel Urban, outgoing MEP for Anticapitalistas, points out, 20 years ago, far-right MEPs struggled to form a parliamentary group in the European Parliament because it meant having MEPs in 7 countries and winning at least 23 seats. Today, they have two large parliamentary groups which, if united, would constitute the second strongest political force in the European Parliament. Over the last ten years, the far Right has emerged in a number of countries where it previously had no seats. That is the case in Portugal with the far-right organisation Chega, which in the last parliamentary elections in March 2024 obtained 18% of the vote and for the first time entered the European Parliament with two seats, after winning 9.8% of the vote on 9 June.

How are the different political groups in the European Parliament distributed, and what are their characteristics?

1. The European People’s Party

The largest group in the European Parliament is the European People’s Party, which is present in all 27 countries of the EU and has 188 seats. It has gained 12 seats over 2019. It includes conservative parties with a Christian connotation, such as the German CDU-CSU of Ursula von der Leyen and Angela Merkel, the Spanish PP, the Civic Coalition (in Polish: Koalicja Obywatelska, abbreviated to KO) led by Donald Tusk, which has governed since the end of 2023, the CDNV in Belgium, and also the party of the late Silvio Berlusconi, Forza Italia. The national parties that support the PP group in the European Parliament have radicalised their right-wing position on issues related to the rights of migrants and refugees, security, war, NATO, the offensive against social rights, the uneasy but very real support for the policies of Netanyahu’s far-right government, the continuation and intensification of neoliberal economic policies of privatisation and undermining of public services, and so on. They have generally included far-right figures in their ranks, as is the case with the New Democracy party that has governed Greece since 2019. EPP member parties make alliances with the far Right, for instance in Spain where the PP has formed an alliance with Vox (a member of the European ID group) to govern regions or municipalities, or in France where part of the Les Républicains party (notably its president, the mayor of Nice, Éric Ciotti) has formed an alliance with Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella’s RN with the approach of the snap legislative elections on 30 June 2024. In Austria, the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) was for years allied with the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ), until a scandal involving the party’s top leader made further collaboration impossible in 2019. Since then, the Austrian People’s Party has been associated with the Greens. In Italy, the member party of the People’s Party group in the European Parliament is Forza Italia, the radical right-wing conservative party of the late Silvio Berlusconi. It is part of the government of far-right leader Giorgia Meloni of the Italian Brotherhood (Fratelli d’Italia), who is also allied with another Italian far-right party, Matteo Salvini’s Northern League (Lega Nord). In Finland, Prime Minister Petteri Orpo’s National Coalition Party (Kansallinen Kokoomus or Kok), a member of the EPP group, has formed a coalition government with the far-right Finns Party (Perussuomalaiset or PS). In Sweden, the far-right Sweden Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna, SD) party supports, but is not a member of, the conservative government in power since 2022, which includes the Moderate Rally Party (Moderata samlingspartiet, M), a member of the EPP. This government is pursuing a harshly repressive policy against migrants and in 2023 made Sweden a part of NATO, which Finland has also done. We should also add that in Hungary, President Viktor Orbán’s far-right party, the Fidesz-Hungarian Civic Union (Fidesz-Magyar Polgári Szövetség) was a member of the EPP until 2021. The list of compromises and alliances of EPP member parties with the far Right is much longer than those mentioned above and should be the subject of a full study.

2. S&D: Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament group, a loyal ally of the European People’s Party in governing the EU

The second-largest EU parliamentary group is the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), which has 136 MEPs, compared with 139 in 2019. The Spanish socialists (PSOE) and the Italian members of the Democratic Party (PD) each won 21 seats, but the Spanish lost one seat (they had 22 in 2019) while the Italians gained 6, up from 15 in 2019. The German socialists (SPD) lost two seats, dropping from 16 to 14. In Portugal, the Socialist Party (PS) fell from 8 to 7 MPs. The Austrian socialists (SPÖ) still have five seats, as in 2019, but have dropped from second- to third-ranking Austrian political force in the EU Parliament. In Bulgaria, the Socialists (BSP) dropped from four to two seats. In Romania, the socialists won six seats, up from four. The Belgian Socialist Party (PS) won four parliamentary seats, up from two in 2019. In Croatia, the socialists held on to four seats. In Denmark, the socialists held on to 3 seats (out of 15); in Finland, they stagnated at 2 seats (out of 21); in Sweden, they retained their 5 seats (out of 21). In France, the Socialists made significant gains, rising from 7 to 13, and are on a par with Macron’s party, which lost 10 seats (while at the same time Marine Le Pen’s RN gained 12 seats, up from 18 to 30). In Greece, the Socialists went from 2 seats in 2019 to 3 in 2024. In the Netherlands, they fell from 6 to 4 seats. In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the Socialists have no seats in the EU Parliament. In Slovenia, they are down from 2 seats to 1. In Estonia and Lithuania, the Socialists held on to 2 seats as in 2019, while in Latvia they fell from 2 to 1.

The Socialist group in the EU Parliament supported the same approaches and the same policies as the European People’s Party, and there was no break between them on the major issues of economic policy, migration policy, increased military spending, the strengthening of NATO and alignment with Washington, the refusal to impose sanctions on Israel, and the choice not to implement a radical shift in response to the environmental crisis.

3. ECR: The European Conservatives and Reformists, the largest far-right grouping.

The European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR) is currently the largest far-right EU parliamentary group, with 83 MEPs

The European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR) is currently the largest far-right EU parliamentary group, with 83 MEPs . Compared to the 2019 elections, this group has gained 14 seats. Giorgia Meloni’s party (Fratelli d’Italia) is the main political force in this group, with 24 MEPs elected in 2024, compared with 10 in 2019. Next is Poland’s Law and Justice party (PIS is the acronym in Polish), which governed the country from 2015 to the end of 2023 and has 20 MEPs compared with 27 in 2019. It should be noted that in 2019, it was the main political force in the country and that in 2024, it was overtaken by the Civic Coalition (in Polish: Koalicja Obywatelska, abbreviated to KO) led by Donald Tusk, who has governed since the end of 2023, as we saw when discussing the EPP. In Spain, the far-right VOX party is part of the ECR group, which won 6 seats in 2024, compared to 4 in 2019. In France, ECR members, of which there are 4, are more or less concentrated in the far-right Reconquête group of the racist Éric Zemmour.3 In Belgium, the NVA, the main ultra-neoliberal and racist Flemish nationalist party, is part of ECR with 3 MEPs (the same number as in 2019). The NVA obtained 22% of the vote in Flanders and narrowly edged out Vlaams Belang in the elections to the federal parliament, which were held at the same time as the European elections. It is NVA’s leader who is leading the negotiations to form a new government in Belgium – a government that will be made up almost entirely of right-wing parties. Vlaams Belang, which is even more right-wing than the NVA, narrowly beat the latter in the European elections and also has 3 MEPs. Vlaams Belang is part of the other major far-right group in the European Parliament, the ID group, dominated by Marine Le Pen’s RN (see below). During the election campaign for the Belgian federal parliament, the NVA adopted a line not too far removed from that of Vlaams Belang in order to avoid losing too many votes to the latter. Bart de Wever, the leader of the NVA, has presented himself as a sort of bulwark against the danger posed by Vlaams Blok. Nevertheless, on election night on 9 June, Bart de Wever was pleased to have (narrowly) edged out Vlaams Blok and congratulated the latter on its improved performance. The NVA’s economic programme is modelled on the programme of the Belgian and Flemish business lobby.

In the Czech Republic, the SPOLU coalition, which is part of the ECR group, has 3 MEPs. In Sweden, the ECR includes the far-right Sweden Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna, SD), who have 3 seats in the European Parliament, as they did in 2019. Finland’s Finns Party (Perussuomalaiset/Sannfinländarna, PS), which lost votes in 2024 and now has only 1 MEP, compared with 2 in 2019. This is good news and shows that the party is paying for its participation in the Finnish government, in which it has 7 ministers. In Greece, the party affiliated with the ECR is the Greek Solution (Ellinikí Lýsi), which gained ground in the 2024 elections, winning 2 seats compared with 1 in 2019. All the ECR’s European parties are clearly far-right.

In any case, it is important to remember that in at least two EU countries, ECR member parties are leading the government: this is the case in Italy and probably will be in Belgium in the coming weeks or months. They are also part of the government of Finland.

4. RENEW Europe

Renew Europe is the fourth-largest European parliamentary group. Its clout has been greatly diminished following the 2024 elections, dropping from 102 seats in 2019 to 75 in 2024. The main political groupings in the Renew group are the party of French President Emmanuel Macron (Renaissance), three right-wing parties from Belgium: the MR, the party of EU Council President Charles Michel, whose term of office is coming to an end; Open VLD of former Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo; and the Engagés, a party which comes from the EPP family and which has just joined Renew after its good performance in the European elections. Also a member of Renew, Holland’s VVD – the party of former prime minister Mark Rutte, who has just become the new head of NATO – is now part of a coalition government led by the far-right party of the racist Geert Wilders (PVV). It was Wilders’s party that propelled the new Dutch Prime Minister Dick Schoof, who was head of the intelligence services and is officially not a member of any party.

5. Identity and Democracy (ID)

The second far-right parliamentary group is the Identity and Democracy (ID) group, which has also grown since the 2019 elections, from 49 to 58 MEPs in 2024. The group is present in 7 countries.

Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella’s Rassemblement National (RN), which came out on top in France’s European elections with twice as many votes as Emmanuel Macron’s party, is the leader in the ID group with 30 MEPs compared to 18 in 2019. Next comes Matteo Salvini’s Northern League, which has suffered huge losses compared to 2019. Its group now has just 8 MEPs, down from 22. Salvini’s party is part of Giorgia Meloni’s government, in which he is deputy prime minister (a position he also held in 2018-2019). Salvini’s party includes far-right personalities who have expressed sympathies with Mussolini, such as former general Vannacci.

Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella’s Rassemblement National (RN), which came out on top in France’s European elections with twice as many votes as Emmanuel Macron’s party, is the leader in the ID group

In Austria, the Freedom Party of Austria or Austrian Liberal Party (in German: Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, FPÖ) was part of the government from 2000 to 2006, and then from 2017 to 2019. Several of its members and leaders have made no secret of their Nazi sympathies. The party was no longer able to be part of a government following a scandal that broke in 2019, which revealed on video that one of its senior leaders had negotiated financing for the party with a Russian oligarch. That said, between 2019 and 2024, it doubled its votes and its number of MEPs from 3 to 6. As a result, it became Austria’s largest party in 2024, beating the EPP member party (ÖVP) and the Socialist Party by one seat in the European Parliament.

In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’s Party for Freedom (Partij voor de Vrijheid) is part of the Identity and Democracy group. It became the country’s main political force in November 2023 and has just formed a government with the VVD, which is part of Renew (see above). In the European elections, it confirmed its position as the leading party by winning 6 parliamentary seats, while Mark Rutte’s VVD won 4. In Belgium, in the Flemish part of the country, Vlaams Belang, a member of Identity and Democracy, made strong electoral gains in June 2024 by becoming the leading party in terms of votes in the European elections. In the Belgian parliamentary elections, it is the second largest party after the NVA, which, as we have seen, is part of the other far-right parliamentary group, the ECR. The ID group is also present in Estonia and the Czech Republic, but these are marginal forces, each having just one MEP.

6. The European Green Group (54 seats compared to 71 in 2019)

The European Green Group suffered a major defeat in the 2024 elections, dropping from 71 MEPs to 54. The group is roughly back to the size it had between 1999 and 2019, before experiencing strong growth in 2019 for the legislature that is ending. It has now slipped from the 4th position it climbed to in 2019 to 6th, overtaken by the two far-right parliamentary groups, the ECR and the ID. The German Greens (Die Grünen), part of a broad coalition government with the Socialists and Liberals, lost almost half their seats, going from 21 MEPs to 12. If we add the other small German lists which also belong to the European Green group, the total has dropped from 25 to 16. The German Greens have accepted the orientation of the government led by the socialist Scholz, which is resolutely in favour of Netanyahu’s fascist government, pro-NATO and in favour of a sharp increase in arms spending. Belgium’s Greens also suffered a terrible defeat, particularly in the French-speaking part of the country where they paid a high price for their participation in a government with two right-wing parties and the Socialists. They have gone from 2 MEPs to 1. The Flemish Greens fared slightly better, keeping one MEP. The Austrian Greens, who have been in government since 2019 with the ÖVP, a member of the EPP, also lost out, dropping from 3 seats to 2. The French Greens (Les Ecologistes, LE), who have adopted an increasingly moderate position without actually being in government, also lost a large number of votes, dropping from 10 MEPs to 5. The exception to this huge downward trend was Denmark, where the Greens increased their number of EP seats from 2 to 3. In Italy the Greens held on with 3 seats in the EP, as well as in Sweden with 3 seats. In Eastern Europe, they are virtually non-existent.

The European Greens suffered a major defeat in the 2024 elections, dropping from 71 MEPs to 51

7. The Left parliamentary group

If the Left does not offer alternatives to disorder, the climate crisis, social insecurity, the management of migration and growing inequality, these issues will be taken up by the far right with a view to excluding, punishing and criminalizing those who are different

The seventh-ranking European parliamentary group is The Left (formerly GUE/NL). At the outset, 25 years ago, it was made up of Euro-Communist parties plus two Trotskyist MEPs – Alain Krivine (Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire) and Arlette Laguiller (Lutte Ouvrière). It expanded to include parties of the Nordic left (Denmark, Finland and Sweden) that did not come from the communist tradition. In 2004 there were no longer any Trotskyist MEPs, but the GUE was joined by Portugal’s Left Bloc (the result of a merger between Eurocommunists, Maoists, Trotskyists, etc.) and Ireland’s Sinn Féin, as well as the Progressive Workers’ Party (AKEL) of Cyprus and the Communist Party of the Czech Republic. In the wake of the 2009 elections, the GUE suffered a major setback, with the various Italian communist organisations losing all representation, whereas they had had 7 EP seats in the previous legislature. The GUE was reduced to 35 MEPs. However, from 2014 onwards, new and fast-growing parties strengthened the GUE – notably Syriza in Greece, which was at its peak – or joined it, like Podemos in Spain, which had just been created and elected 5 radical-oriented MEPs at its first attempt. Spain’s Izquierda Unida also had MEPs. As a result, in the 2014 elections the GUE experienced significant growth, gaining 18 seats, from 35 to 53. Following Syriza’s capitulation in 2015 and the more moderate direction taken by Podemos and Die Linke in Germany, the GUE/NL lost momentum and fell back to 37 seats in 2019. The results of the 2024 elections put The Left (the name that has replaced the GUE/NL acronym) at its 2009 and 2019 levels. The results were positive in France, where La France Insoumise won 4 seats, up from 5 to 9; in Belgium, where thanks to the PTB, The Left won 1 MEP; and in Italy, where the Green and Left Alliance (Alleanza Verdi e Sinistra, AVS) list won 2 MEPs. On the other hand, for the first time in a long time, Izquierda Unida (IU), which includes the Spanish Communist Party PC (IU-PC is part of the Sumar (SMR) alliance, which is part of the government of the Socialist Pedro Sánchez) and the French CP (PC) will be absent from the European Parliament, while AKEL in Cyprus is in retreat. Podemos, which left the government of Pedro Sánchez and Sumar in 2023 on a left-wing line, won 2 seats (compared with 5 in 2019). Anticapitalistas, which had one seat, did not stand again. Die Linke obtained just 2.7% of the vote and lost 2 seats, going from 5 MEPs to 3, having suffered a split organised by one of its former leaders, who created a movement bearing her name: the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht, BSW).

The new party, which won 6.2% of the vote (nearly two million votes) and 6 MEPs in its first election, will probably not be part of The Left. We shall see… The Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance scored high in the former East Germany, sometimes garnering 15% of the vote and coming in third place behind the far-right AfD and Ursula von der Leyen’s CDU/CSU, a member of the EPP. It does not rule out striking an agreement with that party (and with the socialist SPD) to govern the eastern provinces and thus prevent the AfD from coming to power. Sahra Wagenknecht’s new party took votes away from Chancellor Scholz’s Social Democratic Party, Die Linke, the AfD, the Liberals, the Greens and the CDU-CSU. According to Reuters, in order, they amounted to 500,000 from the SPD, 400,000 from Die Linke and 140,000 from the AfD. Sahra Wagenknecht and her party have adopted a position in favour of controlling migratory flows, refusing to send arms to support Ukraine following the Russia invasion and the need to begin negotiations to end the war, etc. They are not in favour of anti-capitalist measures. The environment plays a marginal role in the programme, as do LGBTQI+ rights. The new party cannot therefore be classified as a radical left-wing party, but it would be a mistake to classify it as a right-wing party. In a way, its programme is reminiscent of the programme of the Communist Parties of the 1960s-1970s (such as the French Communist Party): a large dose of protectionism to defend social gains, the pursuit of an alliance with the middle classes and entrepreneurs who invest in national production and create jobs, and opposition to globalized, internationalized and monopolistic capital. It is more an anti-monopoly rather than an anti-capitalist line. We will have to follow the development of the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance closely, without demonizing, but criticizing and debating all the issues that require a clear radical left, internationalist, environmentalist, socialist and feminist orientation.

Among the successes of parties or lists which are part of The Left, we should mention the good results of the PTB (Workers’ Party of Belgium), a party of Maoist and Stalinist origin which publicly renounced those allegiances some twenty years ago.4

In the Flemish-speaking part of the country, the PTB doubled its vote to 8.2% and obtained its first elected MEP in the Flemish Electoral College. In the French-speaking region (Wallonia and French-speaking Brussels), it scored 15.4%, keeping one MEP. While the European elections were taking place, federal and regional elections were also being held in Belgium. In the elections to the Flemish Parliament, the PTB scored 8.3%, representing a sharp rise. In Wallonia, the PTB fell back slightly with a score of 12.1% (down 1.5% compared to 2019) and in French-speaking Brussels, the PTB climbed to 21% (compared to 22% for the PS). In some municipalities in the working-class heart of Brussels, the PTB took more than 25% of the vote, as in Anderlecht (28%), Molenbeek (27%) and the District of Brussels (26%). In central Liège the party scored 16.5%, while in Liège’s industrial suburb of Herstal, the PTB achieved 24.3%. In Charleroi it scored 20%. The PTB has a radical Left orientation and is internationalist, but avoids proposing anti-capitalist measures.

It should be noted that there was also an Anti-Capitalist list (Fourth International) running in French-speaking Belgium in the European elections. In Wallonia it scored 2.5% of the vote.

The most pleasant surprise comes from Italy, where the Green and Left Alliance (AVS) list won 6.8% of the vote and 5 seats in the European Parliament, up from 1 seat to 6. Two of the 6 seats will add heft to The Left, 3 will go to the European Green Group and one is in the non-attached category.

Public debt, which has risen sharply, will be used as an argument to impose more austerity policies

Italian teacher Ilaria Salis, 39, detained in Hungary on charges of violence against neo-fascists during an anti-fascist demonstration in early 2022, was arrested in early 2023 in Budapest and has been imprisoned ever since, facing a sentence of up to 24 years. A candidate on the AVS list, she was elected to the European Parliament and as a result was released. This is very good news. Another piece of good news is that an Italian mayor, Mimmo Lucano, who was threatened with prison by Matteo Salvini’s government in 2019 for allowing a migrant boat to arrive in the port of his small town of Riace, has also been elected to the European Parliament on the same list as Ilaria Salis.

The outgoing MEP Miguel Urban’s analysis of the crisis of the Left is entirely correct. I wholeheartedly endorse it and would like to quote a long passage from one of his recent articles:

“While the Far Right seems to be on the rise throughout Europe, the Left remains stuck in an existential crisis as the smallest group in the European Parliament, and must ask itself what it has done wrong to allow the Far Right to be perceived as an expression of malaise and a vehicle for electoral protest. Why has the Left ceased to be a means of federating discontent and protest, of protesting against the establishment and its ‘gaslighting’ of the people on the bottom rung of the ladder? And, above all, how can we again become that?

For it was only ten years ago that the radical-left SYRIZA coalition won the June 2014 European elections in Greece, a precursor to its victory in the national elections a year later, and that for the first time since the Second World War a force to the left of the social democrats took control of a government in an EU country. Only ten years ago, a new political force, Podemos, burst onto the floor of the European Parliament and, in just over a year, almost overtook the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) with over five million votes and 21% of the vote.

With a few years’ hindsight, we can’t help but recall Walter Benjamin’s classic thesis: ‘Every rise of fascism bears witness to the failure of a revolution.’ A statement which, if extrapolated from its literal meaning, is still relevant for understanding how the rise of authoritarian neoliberalism and/or the Far Right is also linked to the current weaknesses of the Left. This is a useful thesis to help us keep in mind the risks of moderation on the part of left-wing governments and their inability to respond to the working classes’ expectations for change, as happened with SYRIZA in Greece and the PSOE and Sumar in Spain. Because when those expectations are disappointed, dissatisfaction and frustration arise, and the logic of ‘it’s impossible,’ of ‘they’re all the same,’ of the neoliberal anti-politics that feeds the dark passions on which the reactionary international is built, prevails.

The majority of the European institutional Left has yet to learn the lessons of the defeat of the SYRIZA government experiment, of the limits of a reformist project in a context of regime crisis where there is no room for reform, and of the role played by the EU as a concentrated expression of neoliberal market constitutionalism where the set of so-called EU rules prevails over the law of national states and therefore over popular sovereignty. The experience of the first SYRIZA government, the anti-austerity referendum in Greece in July 2015 and the imposition of the austerity Memorandum by the Troika clearly demonstrated this.

If the Left does not offer alternatives to disorder, the climate crisis, social insecurity, the management of migration and growing inequality, these issues will be taken up by the Far Right with a view to excluding, punishing and criminalizing those who are different. The Left needs to understand the crisis of the capitalist regime in which we find ourselves, a crisis which is generating growing discontent among more and more social sectors. On many occasions, the Left is seen as part of the system and therefore part of the problem.

There is no doubt that in a time of crisis such as today, the Left needs to rethink itself – a task that must under no circumstances lead it down a very dangerous path, that of certain fascination with the issues raised by the Far Right: protectionism, exclusionary sovereignty and anti-immigration policies. By not tackling these problems within the framework of rebuilding a project based on the autonomous self-organisation of the working class, with hegemonic ideals and a proposal for an eco-socialist and feminist society, it can seem as if we are trying to ‘challenge’ the proposals of the Far Right, in another vain attempt to mimic the opponent in order to ‘steal’ its successes. Such a tactic may work for the Right when it copies the most superficial aspects of the Left, but it leads the Left to total impotence and self-destruction.” (From an article by Miguel Urban, soon to be published in its entirety)

Conclusions

The Commission, the Council and the ECB are going to increase the pressure to tighten the screws on social spending by EU governments

The rightward shift of the institutions that govern the EU will be markedly accentuated. The Commission, the Council and the ECB are going to increase the pressure to tighten the screws on social spending by EU governments. Public debt, which has risen sharply, will be used as an argument to impose more and more drastic austerity policies. In the battle of ideas, we will have to explain that the governments, the Commission and the ECB wanted to increase public debt in order to finance expenditures in the face of the coronavirus pandemic and the economic and social crisis that has been amplified by it. European leaders and national governments have been unwilling to tax the super-profits of the big pharmaceutical companies – in particular vaccines producers – which have made scandalous profits at the expense of society. The same goes for retail companies – particularly those specializing in online sales and IT services – which have also made huge profits. Then, when gas prices rocketed in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, governments were unwilling to control energy prices and freeze them, allowing fossil fuel and energy companies to also make huge profits at the expense of society. Lastly, when food prices soared as a result of the war in Ukraine and speculation on cereals, cereal companies made super-profits. Just like the major retail chains, which have increased retail food prices disproportionately and abusively, causing a sharp rise in inflation and a loss of purchasing power for the working classes. Governments have refused to impose extraordinary taxes on their profits. Arms production companies are also reaping yet more profits from the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.

In this situation, and with this refusal to levy taxes on the companies that benefited from the crisis and on the richest, the States have increasingly resorted to debt financing instead of financing themselves via tax revenues, except for those from indirect taxes on consumption (Value Added Tax – VAT), which are extremely damaging for the vast majority of the population and in particular for the lowest income sectors.

In the battle of ideas, we need to show that for these reasons, a large part of the public debt is illegitimate and must be audited and cancelled.

The migration policies of European leaders and national governments will also be hardened, and human rights abuses will increase. Human-rights violations will increase, despite denunciations by the European Court of Human Rights and human rights associations.

The climate inaction of European governments and institutions will also worsen.

Rearmament will accelerate.

Far-right rhetoric and policies that support it are likely to continue to spread.

As a result, the antifascist struggle and protest actions against the rise of the Far Right will become increasingly important.

Social movements and political parties of the Left must regain the initiative with a resolute programme for breaking with capitalism and be no less resolute in their efforts to unite.

The author would like to thank Peter Wahl, Angela Klein, Roland Kulke, Fiona Dove, Thies Gleiss, Gerhard Klas, Manuel Kellner, Tord Björk, Raffaella Bollini, Franco Turigliatto, Gigi Malabarba, Miguel Urban, Alex De Jong, Roberto Firenze, Gippo Mugandu and Roland Zarzycki, who answered questions regarding the results of the European elections. Thanks to Maxime Perriot for rereading. The author is solely responsible for the opinions expressed in this article and for any errors it may contain.

Translated by Snake Arbusto

Source >> CADTM

Footnotes

- In addition to Belgium, voting is compulsory in Bulgaria, Greece and Luxembourg. ↩︎

- Miguel Urban, “Who sows far right policies… reaps the far right” | International Viewpoint Fourth International, 10 June 2024, https://fourth.international/en/631 ↩︎

- The four MEPs include Marion Maréchal, who is even farther to the right than her aunt, Marine Le Pen. The three others are Guillaume Peltier and Laurence Trochu, who left Reconquête to start a new conservative party with Nicolas Bay. ↩︎

- In the early 1980s, the PTB denounced Soviet social imperialism as being just as dangerous as US imperialism, and denounced Cuba as the agent of Soviet social imperialism operating in Angola in particular. In May 1989, the PTB supported the Chinese authorities’ crackdown on the occupation of Tiananmen Square. PTB authors argued that the Moscow trials of the 1930s were justified and had not gone far enough in purging elements who were traitors to the communist cause. The PTB tried to rebuild the international communist movement in collaboration and then in competition with Jo Maria Sison’s Communist Party of the Philippines and Abismael Guzman’s Shining Path. It changed direction in the 2000s. It retains a Marxist-Leninist frame of reference. ↩︎

Art (54) Book Review (127) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (46) EcoSocialism (60) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (62) Film (48) Film Review (68) France (72) Gaza (62) Imperialism (101) Israel (130) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (56) Labour Party (113) Long Read (42) Marxism (49) Marxist Theory (47) Palestine (183) pandemic (78) Protest (153) Russia (343) Solidarity (151) Statement (50) Trade Unionism (144) Ukraine (351) United States of America (140) War (371)