Gnosticism and Memes

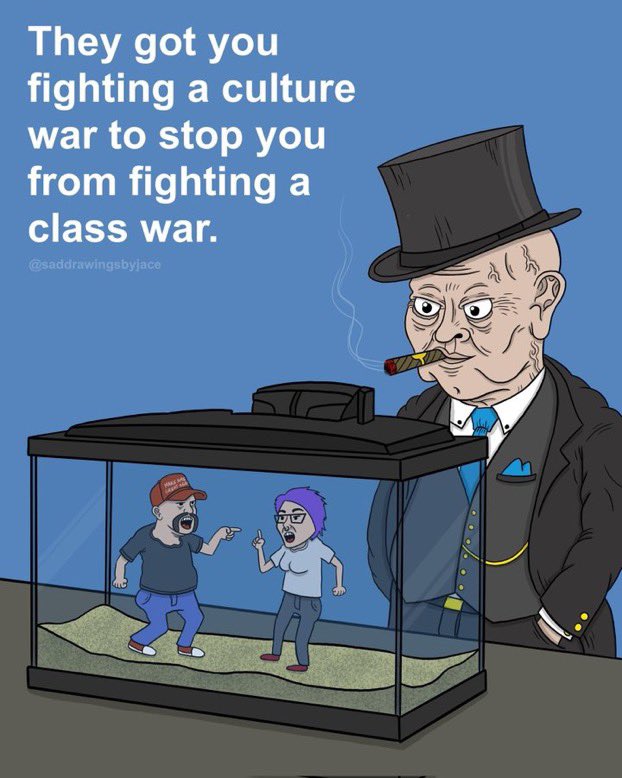

In a meme shared widely by the Twitter left, a heavyset man in a top hat smoking a cigar is depicted leering over a fish tank. Inside the tank are two people engaged in a heated argument. One is a moustachioed man with a MAGA (Make America Great Again) baseball cap, depicting his allegiance to Trump’s politics, the other is a woman with dyed purple hair, evoking stereotypes about so-called Social Justice Warriors (SJWs). Atop this image is a caption that reads, “They got you fighting a culture war to stop you fighting a class war.”

Unfortunately, this image is a fairly accurate depiction of how much of the left conceives the contest of political ideas in the sphere of culture. Far right political hack and self-styled critic of Hegel, James Lindsay, likes to accuse the left of indulging in Gnostic beliefs. This is an old accusation, earlier popularised by the American philosopher Eric Voegelin. It is nonsense for various reasons: the accusation is vague, what is meant by Gnosticism is unclear, the transmission of ideas is unevidenced and the similarities are cherry picked.

However, it is fair to say that the meme, which expresses the view of a quite reactionary strand of the left, has a certain emblematically Gnostic flavour. In a vulgar version of what is deemed Gnosticism, a demiurgic figure creates a fake reality, the world in which we live, to trap souls, who can only escape from this artificial and in some sense irreal prison through gnosis (spiritual knowledge). In the meme, a kind of monopoly man demiurge has MAGAs and SJWs caught in his fake, fish tank reality, distracted from the truth of his existence.

But to point out that an idea is similar to something else is not to criticise it. To do that, it is necessary to go into more depth about why such a conception of ideas and reality is unpersuasive, and what alternative conception should replace it. Fortunately, as Marxists, we belong to a tradition that offers just such an alternative, a point that Voegelin and Lindsay have consistently failed to grasp. Even more fortunately, Marxism is by no means unique in this respect; there are a great many fleshed out alternatives, and many of them complement and expand on Marxist assumptions.

Racism and Propaganda

Quite recently geneticist and anti-racist campaigner Dr Adam Rutherford shared a clip of white supremacist Douglas Murray spouting his usual bile about the superiority of “Western” civilisation, the uniqueness of its valuing of courtesy, and its varied contributions to the sciences and culture the he vaguely suggested non-“Western” peoples were disrespecting. Rutherford commented:

“The reliably wrong Douglas Murray here cosplaying as a pantomime racist to shill his appallingly written ignorant snowflake book. And he’s pretty good at it, the silly goose.”

Rutherford can talk expertly on why the scientific claims of racists are meritless nonsense, but is he correct in his estimations here? Specifically, is Murray good at it, in all seriousness? That courtesy is somehow “Western” is clearly nonsense. Everything else Murray asserts plainly relies on stripping historical context from historical claims, and the construction of the “West” as autonomous is indefensible—in part because the “West” is itself an indefensible canard.

Murray is undoubtedly posh, but otherwise as a person he is much the same as any raving white nationalist. He is also helped along by his connections to the US-based Pioneer Fund, an organization with ties to the historical Nazi Party whose primary activities involve the funding and distribution of pseudoscientific studies on race, which then go on to form the basis of documents sent to American politicians, intended to influence policy. That is, he is one part of a wider infrastructure of far-right thought, a manifestation of it more than its author.

The sociologist Max Weber characterises charisma, correctly, as being about the contextual ability to influence, a “purely de facto ‘recognition’, whether active or passive, of his personal mission by the subjects, on which the power of the charismatic lord rests”. That is, someone might exert influence because they are a King and considered divine, even if they are not particularly clever talkers or persuasive thinkers. Likewise, Murray’s social position is a worthwhile subject to explore, beyond Rutherford’s claims. We need to better understand such networks, along the lines of grassroots research on the far right such as that carried out by the Podcast ‘I Don’t Speak German’.

Still, the problem with framing the spread of racism as an issue of individual racist propagandists is that it misunderstands how ideas function socially. When Marx made the argument that, ‘The ruling ideas are the ideas of the ruling class’, he was not making a Chomskyian observation about the nature or importance of media power. Rather, his point is that society is permeated by these ruling ideas, because it is made in the image of the ruling class. This permeation does not occur abstractly but in the ways we live. Ruling ideology is less about Fox News and far more about ordinary rituals. Fox News et al. merely augment and reaffirm ideas that people imbibe from how they work; learn; buy goods; are raised and raise their children; conduct their relationships; etc.

The Russian psychologist of education, Lev Vygotsky, powerfully argued that language only merges directly with the cognitive capacities of the child (rather than being a separate system controlled by cognition) after they adopt speech socially. How one is socialised as a young child, the attitudes and dispositions of their parents, has a direct influence on the cognition of the child because socialisation merges with direct cognition. This is linked to why bigotry is reinforced. Parents who adopted bigotry as an adult go on to raise children for whom bigotry becomes “coded” into their cognitive processes.

The key takeaway is that propagandists, like Murray, are not that clever. They would be nowhere without leaning on the organic consciousness of the ordinary. Being persuasive is not relevant to the transmission of racist opinions. These beliefs spread not because such charlatans are talented at sophistry, but because we occupy white supremacist cultures that affirm such beliefs in everyday life. These views are bottom-up, not top-down.

This in turn has massive implications for how you can go about challenging racism and other bigotries. It means debating and debunking the likes of Murray, while potentially fine in itself, does little to shift the more substantive problem. Because Murray is an outgrowth, a malignant and festering symptom, not the cause of racism.

To challenge racism you must, in fact, first challenge its social transmission, embedded in what Markus Wissen and Ulrich Brand describe as the imperialist mode of living (in a book of that title). A mode of living in this sense is “a global constellation of power and domination that is reproduced—through innumerable strategies, practices and unintended consequences—at all spatial scales.” A more customary term for Marxists might be Praxis, a unity of theory and practice in a state of constant self-becoming. The essential point is that ways of life transmit certain assumptions and ideas.

Accepting this, to combat certain ideas and promote others you must do so at the levels of social reproduction (the maintenance of families and workers) and economic production (on the shopfloor, in offices, building sites, kitchens, etc.), and thereby in how we live and see. It is not enough to abstractly debate and criticise, to seize control of certain information apparatuses or just formally democratise schools, media, the internet, when how people operate in every sphere of life is fundamental to how they think.

Understanding Consciousness and Experience

The term false consciousness has fallen out of favour with many Marxists, who have come to prefer ideology instead. It is understandable, as the former term is heavily associated with the idea that people who do not believe as Marxists believe are somehow being hoodwinked. That is a shame, because against the dry abstraction of semi-autonomous ideas ruling peoples’ lives, the emphasis on the experiential aspects of life in fact takes people far more seriously.

Aligned as much with the insights of the Classical American Pragmatists as with Marx, and most explicitly in the work of William James, consciousness can be understood to be false because it is contrary to the flourishing of those who bear it, not because it is wrong in some outsider perspective. It is not false in the thin way that evil is to be desired is false, but in the thick sense (more substantially descriptive) that, for instance, racism is maladaptive to the good life.

Standpoint theory, a theory of knowledge (or epistemology) brings together a notion of consciousness that is useful to describe the ways in which ideas operate. In her essay ‘Feminist Standpoint Theory’ Linda Gurung describes it as a method concerned with the embodiedness of inquiry, in which the objectivity of a ruling perspective is constructed from assumed, dominant experiences, such as those of men. Contrary to this, theories that go against the ruling ideas are ‘earned through the experience of collective political struggle’.

Gurung identified four central theses of feminist standpoint theory. First, that it acknowledges the relationship between the subject and object in an inquiry; second, that knowledge is situated, in that there are distinct ways of knowing attached to particular social positions; third, that it is possible to have what is called epistemic advantage, which is the idea that the oppressed and marginalised have a greater epistemic authority by virtue of having to endure struggles, granting them completer and more diverse knowledge; and forth, that power relations are central to knowledge production and proliferation.

As a standpoint theory of the working classes, Marxism properly admits to no outsider perspective. That is why Marx was not a moralist when it came to bourgeois values; such values could be condemned, but only from another perspective. This is to acknowledge the bourgeoisie are not inherently internally wrong, and a working-class person who adheres to bourgeois values is acting falsely only in a specific sense.

Another thing the marks out Marxism as a standpoint theory is that Marx, exactly like the feminist standpoint theorists, did not see standpoints as relativistically equal. The working-class standpoint was not ‘better’ by some metric outside of human perspectives, but it is uniquely placed to affect the universal liberation of human potentialities, and its ethics is one that emphasises the open possibilities of that future.

Although this goes beyond the explicit arguments of Marx, we can argue here that ethics for us must be a futural virtue ethics rooted, as Marxian philosopher Ernst Bloch argued, in hope as constitutive of all human consciousness. That is because modern ethics, unlike virtue ethics, always posit some fundamental ahistorical outsider grounding axiom (irrefutable idea) by which to test ethical claims. This makes an ethics grounded in a historically situated consciousness, embedded in daily action, impossible. By contrast, virtue ethics sees ethical development as related to the way in which practices shape human flourishing.

The model of human flourishing proposed by Marx is one with a stress not on a list of religious or philosophical ideals, however, but on expanding human freedom. If the expression of working-class revolutionary politics is liberation from the domination of class society through the abolition of class, including the self-abolition of the working class, then it is easy to see how it must oppose the kinds of racism and general prejudice common to capitalist and premodern class society.

Such a theory of ethics and ideas needs working out beyond Marx. His early humanist project, taken up by Engels right until the end of his life, is woefully incomplete. But even a sketch of it shows its superiority to a model of ideas and ideology that sees the problem of racism in terms of individual polemicists spreading bad ideas to unthinking subjects. This model is sadly popular on a left fixated on the ephemera of media over the greater totality of life in which that media is situated, and the types of experiences, ethics, standpoints, and consciousness that this totality gives rise to.

It gives a highly limited truth to the charges of Gnosticism, but more seriously to the charge of dualism, made against the left. As socialists, we must seek a better understanding, one capable of making judgments about social phenomena while not dismissing human agency and the texture of human life in and beyond class society. Unless we can do so, it is unlikely that we will ourselves cultivate forms of praxis and organisation ever capable of going beyond class society.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women

How are we to determine what constitutes a “good life” without proscribing something from outside the standpoint of any one given group?

This is a great question. We don’t unpack the idea of standpoint sufficiently here. And a futural virtue ethics needs developing, too. A very short answer is that revolutionary struggle is the discovery of a virtue ethics, of a conception of the good life, that cannot exist independently of that process. It should not really be a conception of the good life, but of good lives. These are the questions we are hoping to address in our next essay.