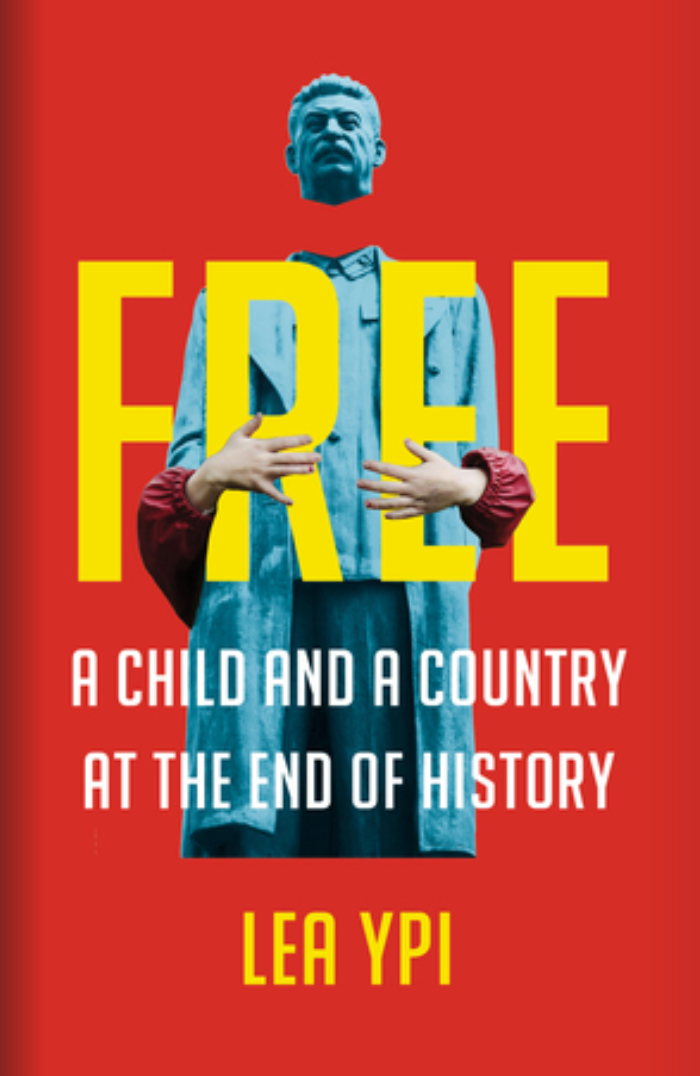

Free: Coming of Age at the End of History by Lea Ypi is published by Penguin Books.

This book strikes some personal chords. I nearly joined the Communist Party of Britain Marxist-Leninist in the mid-1970s, a time when they had broken with China and thrown in their lot with Albania, which they described in the title of one of their pamphlets as “the most successful country in Europe.” This was the group that Alexei Sayle was once part of. We read Lenin, and long-haired scruffy comrades came back from visits to the most successful country after being shaved short at the border. You would have believed that they had visited heaven, but they had not.

Transition

This book gives us a striking child’s-eye view of the transformation of the country in 1990, when Lea Ypi was 11 years old, through to the “civil war” of 1997. In the eyes of this child, the years before 1990 were a time of hope for the possibility of a transition from socialism to communism. After the Enver Hoxha regime broke from the Soviet Union and then from China, to be all the more isolated, those years of her life, from 1979 to 1999, were in some ways confusing times and in some ways certain about what was to come.

All of that certainty was to fall to pieces after the fall of the Berlin Wall, even though the regime was convinced that this defeat of the “revisionists” would have no real consequences for them, but in 1990 the “democratic” transition hit them too. It was a transition from socialism, not to communism, but to brute neoliberalism, with the privatisation of enterprises and services leading to mass unemployment and precarity and with pyramid schemes scamming large numbers of people. A consequence of that rapid escalation of exploitation from 1990 through 1997 was bloody conflict and attempted coups that led to thousands of deaths.

The image that was fed to well-meaning political tourists, as well as sun-seekers, was that this was a haven, but Lea Ypi, as an insider, unravels that image neatly in a detailed description of the separation of the population from the outsiders. The book is beautifully written, with a compelling motif structuring each chapter; for example, the purchase of a Coca-Cola can by a member of the family and its disappearance is the occasion for vitriolic accusations and the breakdown of relationships between families and neighbours. The picture we have is very different from the ideological framing of Albania as descending into chaos because of the flare-up of old tribal rivalries.

Divisions

The conflicts are structured, as social conflicts always are, and it is crucial to understand how they have a historical genesis as well as how people try to overcome divisions that enable those in power to retain their grip. Ypi shows us a world before 1990 that is structured by lies and self-deception, those of her family included, and by the painful attempts to speak about oppression without actually naming it in front of the children, something that would put the whole family at risk.

Most painful are the revelations that come as 1990 unfolds; we learn that the family discussions about who has ‘graduated’ and who has been ‘expelled’ from this or that university, for example, are really about who has been arrested and imprisoned and who has been executed.

And then, with the arrival of full-blown economic “shock therapy,” comes “structural adjustment.” The mother becomes an activist in the Democratic Party, an opposition group that is closely tied to Western NGOs keen to fight “corruption,” while the father is reluctantly caught up in new managerial practices. He must fire workers at the company he has been hired to make efficient and does not want to; he points to them assembling outside the building and says, with anguish, that those people are being turned into objects; look out there, he says, there is “structural adjustment.”

Freedom

Those who were linked to the old regime before Enver Hoxha’s gang came to power are trapped in their “biography”, assumptions about who they are and where their loyalties lie that effectively operate as a form of divide and rule. There is division, but there is also, as Ypi shows, much solidarity that was destroyed, deliberately destroyed, after 1990 in order to allow capitalism to run rampant.

The “free” in the title is ironic and sarcastic. Some in the family embrace this freedom, and the language of socialist struggle is wiped away from their speech. Some engage in hopeless, nostalgic searches for freedom that existed before the regime was installed and end up disappointed. And some come to realise that freedom is something very different from how it is painted, either by Hoxha or by new false friends from the West.

The grandmother, a supporter of the French Revolution as the best example of the struggle for liberation, tells the young author that freedom is being conscious of necessity. And now Lea Ypi, able to write this biographical account that reworks “biography” not as a trap but as a space for critical reflection, takes this seriously. The book is about how we become conscious of necessity, but also how we live it. It poses choices about how we will be free.

Lessons

Lea Ypi, now a respected academic at the London School of Economics, is writing this account from the left, and the book includes some reflections towards the end on the way some on the far left reacted to her “biography,” which makes for uncomfortable reading. She clearly had to deal with some crass assumptions about the failure of socialism in Albania, including the claim that the country was backward or that bureaucratic mistakes were made that simply would not be made by an enlightened Western left vanguard.

Publication of the book in the UK last year – this US edition has been published by Norton this year – embroiled her in further problems. It was lauded in the liberal press and read as if it were testimony to the necessary failure of Marxism, not a lesson she herself subscribes to. And there were some nasty reviews by quasi-tankie critics who were too quick to point to the honest revelations about the complex family history she herself is clear about in the course of the book.

The book needs to be read by the left, addressing misconceptions both about Albania and about the nature of “actually-existing socialism” in general. It is a generous open account, and needs to be read generously by us revolutionary Marxists, learned from, and responded to as in a debate with a comrade. She was a comrade there in Albania, related to others as such, and she has made the best she could now of that bitter history. That history is ours too, and now we must know better what to make of it.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Protest Review Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women