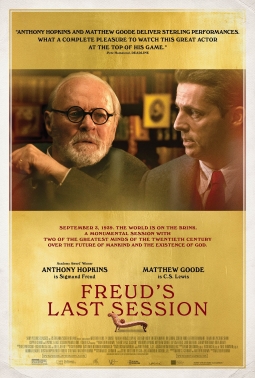

The Freud’s Last Session film arrived in cinemas here last week, with Anthony Hopkins as an irascible but unexpectedly jolly Sigmund Freud improbably meeting up with a rather smug sneering C S Lewis (played by Matthew Goode). This encounter was at the Freud house in Hampstead in 1939, just three weeks before his death (from a dose of morphine administered, at Freud’s request, by his doctor Max Schur). The film was adapted from a stage play, which was, in turn, inspired by a book called “The Question of God” by an evangelical Christian psychiatrist who was a founder of the right-wing homophobic “Family Research Council” in the US. So, the film comes with a line, a staged encounter that never happened between the atheist Freud and an Anglican convert.

Religion

C S Lewis was apparently a bit of a bully and a snob, and was part of a little literary circle at Oxford cringingly called “The Inklings,” a group that included the devout Catholic J R R Tolkien (who was dismayed when Lewis went Anglican; Tolkien said that he wrote his own mythological fantasy stuff to lure readers into truth about Christ). You can get a flavour of Lewis’ theology and politics from his comments on Freud and Marx, where he evidently sees them as twin threats. The Church Times thought the duel between the two men in the film amounted to a draw, but the “Gospel Coalition” was annoyed that the line of the “excellent” original book was not faithfully carried through into the film. Thank heavens for small mercies.

The Gospel Coalition was particularly enraged by the addition of what it called “a lesbian sub-plot,” and by C S Lewis mis-quoting the Bible to Freud. When Lewis says that sex should be between “two people who are committed to one another,” he should, of course, according to these devout viewers, have specified that this should be between a husband and wife; instead C S Lewis was made out to be what they term a “progressive Christian.” I learnt from reading around after the film, by the way, that “apologetics” is a respected part of theology, not, as Freud jokes in the film, an apology for Christianity and, by implication, its antisemitic history.

Sex

There are plenty of bad faith arguments tossed backwards and forwards in the film, some poking around into childhood reasons why Freud might have rejected a fatherly god and why Lewis might have craved for one. In this sense, you could call the staged debate in the film a draw. However, the mode of argument plays to a popular misconception of psychoanalysis, which is that, in order to be at all credible, the theory should have been invented by someone who was above and beyond all of the human tangled mess he was drawing attention to. It evidently was not, and Freud was as messed up as the rest of us, imperfectly noticing what he experienced as well as what he thought his patients were talking about.

There is plenty that is problematic about psychoanalysis, but the Lewis barbs in the film are mis-directed. Attempting to settle theoretical (or theological) questions by ad hominem argument misses the point. There are political institutional issues that we really instead, need to focus on. One of these issues concerns organisation and transmission, something that is touch on in the film.

One of Freud’s patients was his daughter Anna Freud, and another was her life partner Dorothy Burlingham. There is much speculation as to what the relationship between the two of them actually amounted to, and this is where the so-called “lesbian sub-plot” comes into play. In the film we are presented with two oppressed lovers, Anna pathologically dependent on Freud the father, and (plot-spoiler) eventually coming out to dad. That declaration of love for Dorothy does seem to be pure fiction. Anna herself always categorically denied any sexual relationship with Dorothy. Given the state of psychoanalysis as an institutionally homophobic practice until very recently, it would be understandable that she deny it (though if there was such a relationship, that denial would be something of a betrayal to out gays and lesbians who have fought for a voice in the “talking cure”).

Animals

C S Lewis is sent out to take the dog for a walk when Ernest Jones turns up to talk to Freud. Yes, Freud liked dogs, nobody is perfect, and he never (as is often mistakenly quoted and as my fridge magnet has it) said that time with cats is never time wasted. That dog, by the way, had been dead for two years by 1939, as Hannah Zeavin pointed out in a thoughtful and trustworthy piece written when the film was screened in the US last last year.

Anyway, in the film we have a flashback to Ernest Jones in Vienna defending Freud, and Jones was certainly instrumental in getting the Freud family out to relative safety in London after Anna was briefly arrested by the Gestapo. The screenplay has it that Jones still has a thing for Anna, and wants to talk to Freud about it in 1939. This is very unlikely, since Jones had already been warned off such a relationship by her dad, and by this time Jones had made a strong alliance with Melanie Klein, who arrived in London much earlier, in 1926, and had set up shop, forming a strong group of supporters in the British Psychoanalytic Society. (One of Klein’s most celebrated case studies, by the way, is of one of her own children, bad move.)

Freud’s house was reconstructed in Dublin for the film, not shot in London, and the New York Times complained, with a little dig at the production here, that the film seemed to lack a cinematographer. The look of the film is quite subdued, a bit wordy, but you wouldn’t expect the debate in the film to end up with Lewis administering the final dose of morphine that finished Freud off. Neither should you expect Hopkins to mimic Freud’s accent; in fact, the terrible pain that Freud was experiencing by that point in his life and the problems with the prosthesis in his mouth would not have made for easily comprehensible dialogue.

The audience was small in the nicely restored cinema in Marple south of Manchester, and the owner had things to say about it to, which does not happen in anonymous multiplex media outlets. We need spaces in which to think and speak, and speak differently. Psychoanalysis is one of those spaces, and that’s one reason it is set against mass neuroses, of which institutionalised religion is one.

Much had to be fabricated to make this particular production work as a play and as a film, and much of that was quite unnecessary. The arguments are tendentious, and there needs to be a better more accurate rendering of the problems and possibilities of psychoanalysis for us really to face and work through the past of this potentially radical resource for left politics.

Art (54) Book Review (122) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) EcoSocialism (56) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (59) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (70) Gaza (61) Imperialism (100) Israel (127) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (55) Labour Party (113) Long Read (42) Marxism (50) Marxist Theory (48) Palestine (175) pandemic (78) Protest (152) Russia (340) Solidarity (145) Statement (49) Trade Unionism (142) Ukraine (347) United States of America (133) War (368)

Freud wrote that the future

would decide whether there

was more fantasy or truth

in his, Schreber’s or Lewis’s ideas.

Thanks, interesting. i

Your article is commendable. Well done!

1. The concepts of apologetics and polemics are best understood within the framework of the inquisition. When intellectual arguments fail, coercive measures often come into play to enforce conformity. Esteemed figures such as G.K. Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, and Cardinal Newman, while historically significant, may seem less pertinent to those with a more liberated mindset.

2. I was intrigued by the film’s emphasis on homosexuality over Thomas Aquinas’ five proofs for the existence of God. This focus becomes clearer when considering the background of Armand Nicholi, the author of ‘The Question of God.’

Thanks, interesting comments, I see that Nicholi, who was a psychiatrist, was also actively against the depathologising of homosexuality by the American Psychiatric Association after their historic vote. I