Each time I have been lucky enough to have some time in Manchester I have been more and more impressed with the work of the people running Manchester Art Gallery. It has been going for nearly 200 years and its collections were built on the wealth of the new bourgeoisie of the industrial north. In her introduction to the gallery catalogue curator Liz Mitchell notes:

Manchester Art Gallery was founded in an attempt to address some of the worst excesses of the industrial world. But there is no escaping the fact that the wealth that made it possible was built on labour, and that the majority of those who laboured were not afforded a share of those riches or a say in how they were used (…) Wealth and poverty still sit side by side (…) What can art do? It may not have the answers to the world’s ills, but it can help open eyes and hearts and minds to new ways of thinking about them. (…) Manchester Art Gallery today strives to be a place both for and of the people of the city – a place of shared creativity in which one can find both sanctuary from the challenges of 21st-century life, and a space for the open discussion of ways to make it better.

pg 20, The Collection, published by Manchester Art Gallery, 2020.

If people on the left had to come up with a progressive definition of what a city art gallery should be then you would find it hard to do much of a better job.

These might be just fine words, aspirations on paper but the actual work the gallery has done in the last few words shows they are trying to put the rhetoric into practice.

The Male gaze challenged

In 2018 the gallery found itself in the eye of a media storm – a battle in what has become known as the culture wars. Sonia Boyce, an artist commissioned by the gallery, staged a performance during which one of the most popular Victorian paintings in the collection, J.W.Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs (see above), was temporarily taken off display. As the catalogue notes (pg 13 op cit):

The work was an intentional provocation, a questioning of how art and its perception impacts our understanding and treatment of gender, class, race and sexuality. It drew attention to the way decisions are made about what is shown (…) It raised questions about public ownership and how the cultural legacies of the past inform understanding in the present. Far from ‘killing the conversation’, as one critic claimed, it drew international attention.

A picture like this one had traditionally been reverentially defined as a history painting on a classical myth that totally obscured its function as a product of gender relations – a male artist catering to the tastes of well off Victorian gentlemen who enjoyed a bit of erotic stimulation in their mansions. Looking only at Watershouse’s undoubted technical, colouring and compositional skills does not eliminate this level of analysis. Did the young women servant, often abused by the same gentleman, see the same meaning in the picture as her master?

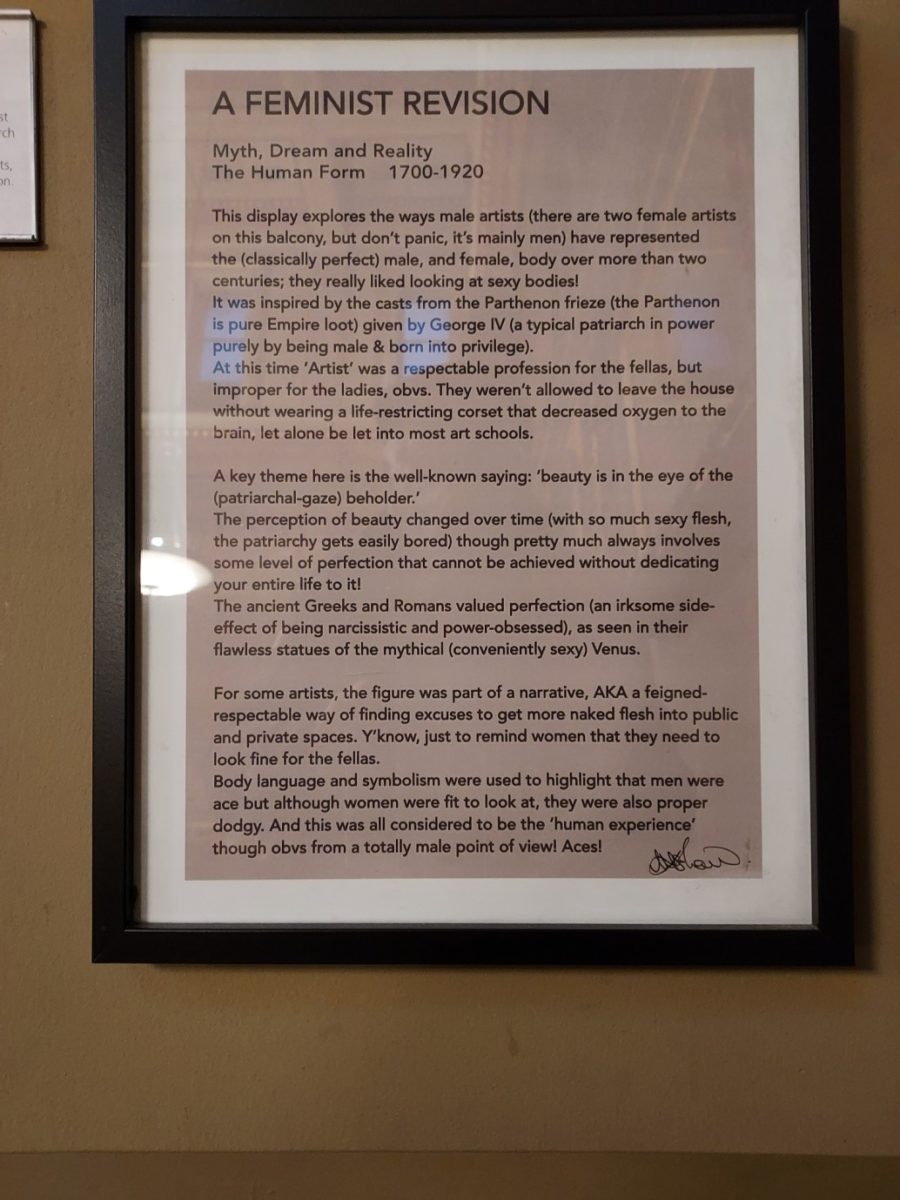

Indeed it is possible to appreciate its artistic merits and at the same time interrogate its meaning in this way. Classic myth can be used to perpetuate Victorian notions of gender and power. Right down to Johnson today the Classics have played an important role in the identity, entitlement and self-perception of the English ruling class. The painting was restored to its place whilst additional commentaries giving a feminist viewpoint were added to the gallery displays. Those captions telling you about a picture are never totally neutral.

You can still see in the gallery a video presentation of the performance evening organised by Sonia Joyce in 2018. It shows the removal of the Waterhouse picture and the questions posed to the public. There are costumed acts responding to the 1826 portrait of a black actor playing Othello and interventions by four drag artists.

Uncertain futures – engaging with women workers

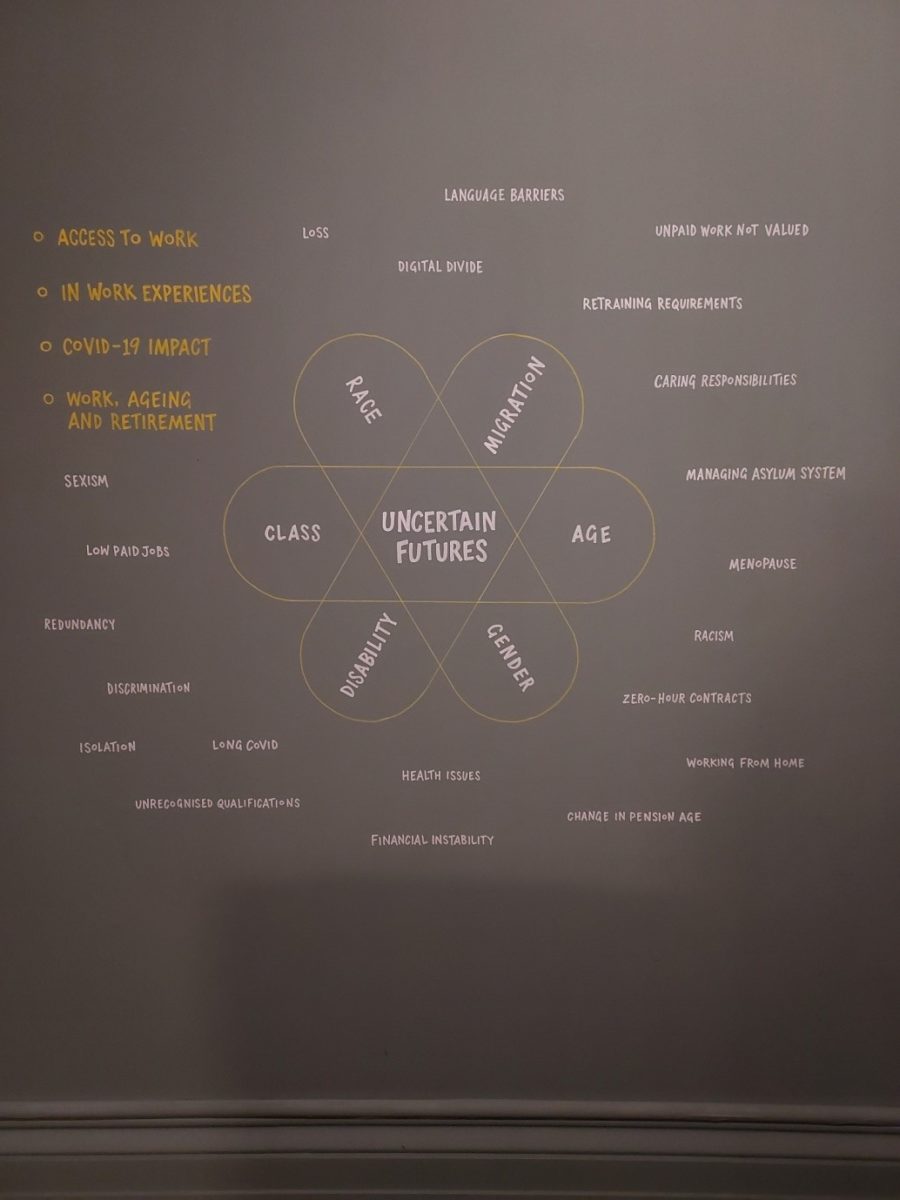

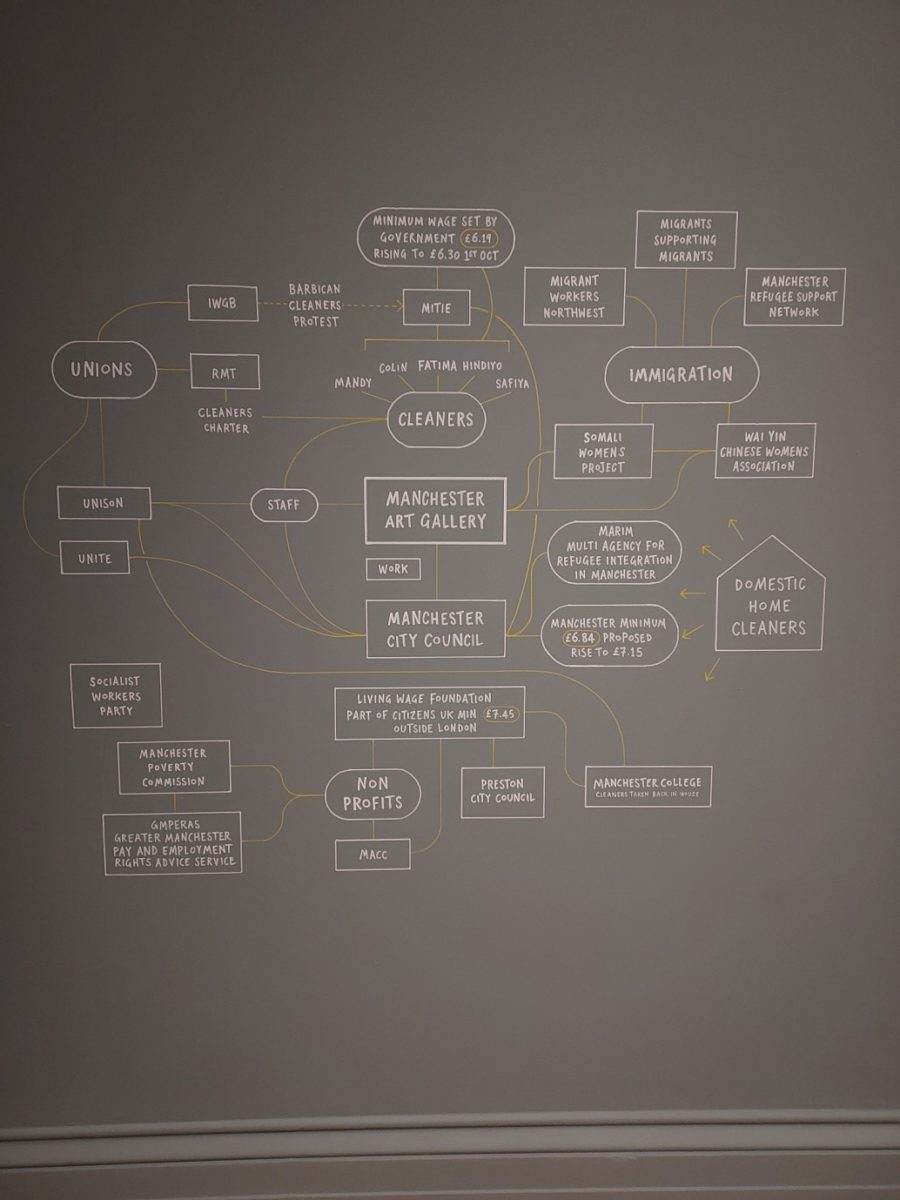

At the moment there is an exhibition about the work the gallery did with its own cleaning staff and a hundred other low paid women workers who are over 50 years of age. Women workers over 50 are often less visible and with less voice. Devised by US-based artist, Suzanne Lacey, it collected oral testimonies of women workers who were older and being hit by the new pension laws that meant they had to work longer to get the state pension. A room has been set up like an interview area and you see and hear the spoken words projected on the wall. You can also take and read one of the dozens of clipboards with the details of their individual stories. The displays below show the breadth and depth of discussions that were held. The local Labour council also collaborated with the project. One of the positive results of all this has been an agreement about in-house cleaning with the Manchester living wage.

Cleaning conditions -Sweeping the gallery

Art has a lot to do with solving problems. Art affirms identity. Art gives voice. Art expresses difference, and it expresses consensus. Art brings up issues.

Suzanne Lacy, In Motion Magazine

The Uncertain Futures project was foreshadowed by an earlier performance by Lacy called Cleaning Conditions organised in 2013 where a team of volunteers from low paid workers campaigns, trade unions and migrant organisations came and swept the gallery each day for two weeks. The sweeping involved miniature coloured political brochures which were distributed around the gallery and then swept up. There is a video you can see, showing this and the public discussions that were held at the end of each day by the participants about the challenges of organising to improve cleaners working conditions and wages. Each day they started and ended in front of Ford Maddox Brown’s famous Victorian painting, Work (1852-65), shown below:

Alongside these exhibitions, there is one called Trading station which looks at how hot drinks, once expensive luxuries for the few, have enriched our lives, promoted the exchange of ideas and influenced the design of our homes. Trading Station traces the history of how these drinks arrived in the UK, revealing their global histories, connections to slavery and colonisation and contemporary ethical issues.

Another room selects a number of pictures and objects from the collection and engages public debate about what they represent to different people. Videos relay the contributions of the public. It is part of a bigger discussion about public participation in guiding the sort of art gallery the people of Manchester would like. In 2019 it attracted 750,000 visitors so the team in charge is certainly doing something right. When I was visiting it was buzzing, including with lots of younger people. The Tate Modern scooped away former Manchester Art Gallery leader Maria Balshaw in 2017 and we have seen similar positive changes in that place too. Women curators are doing some of the most exciting curatorial work today as we can see in Manchester and at the Tate.

Coming up from the 2 December there is an exhibition of Derek Jarman’s work called Protest. Can this gallery do any better?

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Protest Review Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women